Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Globalization and the Elite Chasm

Globalization and the Elite Chasm

I read with great interest David Frum’s piece on the Great Republican Revolt, Jon’s reply to it, and all of your comments. I’m very frustrated by my inability to find good polling data — as opposed to impressionistic and obviously partisan sketches — about who Trump’s supporters really are and what their political preferences really are. I don’t know whether it’s true, as Frum suggests, that there’s an important equivalence between between them European populist parties, as Frum believes:

You hear from people like them in many other democratic countries too. Across Europe, populist parties are delivering a message that combines defense of the welfare state with skepticism about immigration; that denounces the corruption of parliamentary democracy and also the risks of global capitalism. Some of these parties have a leftish flavor, like Italy’s Five Star Movement. Some are rooted to the right of center, like the U.K. Independence Party. Some descend from neofascists, like France’s National Front. Others trace their DNA to Communist parties, like Slovakia’s governing Direction–Social Democracy.

These populists seek to defend what the French call “acquired rights”—health care, pensions, and other programs that benefit older people—against bankers and technocrats who endlessly demand austerity; against migrants who make new claims and challenge accustomed ways; against a globalized market that depresses wages and benefits. In the United States, they lean Republican because they fear the Democrats want to take from them and redistribute to Americans who are newer, poorer, and in their view less deserving—to “spread the wealth around,” in candidate Barack Obama’s words to “Joe the Plumber” back in 2008.

I hear this a lot in France, too, from friends who are sure that Trump and the National Front represent the same phenomenon. If Frum’s description were all I had to go by, I’d say, “Yep, that sounds about right.”

But I suspect it’s far too superficial. France and America are different countries, with different histories. I’ve never found it useful to draw analogies like this, and indeed I find that it often leads to catastrophic analytic mistakes. (In intelligence analysis, it’s called mirror imaging.)

Frum’s diagnosis — much like Bernie Sanders’ — is that we’re seeing a war of the ultra-wealthy against the middle class: “The GOP donor elite planned a dynastic restoration in 2016. Instead, it triggered an internal class war.”

John concedes that he doesn’t personally believe that illegal immigration is the biggest issue facing the country. Nor do I. But he suggests that it’s “become a proxy for the chasm that divides the elite from everyone else,” and thus recommends the GOP focus on proving that no matter what the elites want, the GOP sides with “everyone else.”

I’m not so sure. I’m wondering if the undiscussed elephant in the room here, intellectually speaking, is globalization.

Joseph Eager left a comment beneath Jon’s post that seems worth exploring a bit more:

Frum also seems to be underappreciating the importance of immigration policy, the point of which is to shift distributional policy away from redistributing income directly and towards redistributing capital (in the sense of stuff that makes people more productive).

The evidence that income-based redistribution is ineffective goes back centuries, while policies that redistribute capital are probably what caused the Industrial Revolution. It’s not like we don’t have a great deal of historical experience with this stuff. Use immigration to tighten labor markets; create a fiscal surplus to increase the supply of financial capital (so employers can invest in productive capital for their workers) and voila, rising wages for the masses. It’s not hard.

Well, it is hard. Because you can tighten the labor markets all you like, but you can’t prevent capital from moving to countries where labor’s cheaper without imposing capital controls.

I agree: Policies that redistribute capital are part of what caused the Industrial Revolution. But what we seem to be forgetting is that China and India are now going through the Industrial Revolution, as are many other countries. Until the whole world is as wealthy as the United States and Europe, labor will continue to cost less overseas than it will in the highly-developed world. As the moneyed elite knows perfectly well:

Not long ago, Apple boasted that its products were made in America. Today, few are. Almost all of the 70 million iPhones, 30 million iPads and 59 million other products Apple sold last year were manufactured overseas.

Why can’t that work come home? Mr. Obama asked.

Mr. Jobs’s reply was unambiguous. “Those jobs aren’t coming back,” he said, according to another dinner guest.

The president’s question touched upon a central conviction at Apple. It isn’t just that workers are cheaper abroad. Rather, Apple’s executives believe the vast scale of overseas factories as well as the flexibility, diligence and industrial skills of foreign workers have so outpaced their American counterparts that “Made in the U.S.A.” is no longer a viable option for most Apple products.

The manufacturing jobs will not come back. Nor will mine: My skills are now mostly obsolete. The massive and rapid transformations of the digital age, globalization, and the global Industrial Revolution have changed the world of everyone alive. My own industry was creatively destroyed, along with those of many Americans my age. I expect that my life will from now on be characterized by economic insecurity bordering on terror. This grows more frightening with age and the prospect (and ultimate inevitability) of illness. So you bet I fully understand why other once-secure middle-class Americans do not appreciate being creatively destroyed. Creative destruction sounds great on paper. It doesn’t when it really happens to you.

But I’m not sure that the chasm is a class war so much as it’s an intellectual war between those who think rapid technological change and globalization can be controlled and those who see these forces as, literally, unstoppable absent the imposition of totalitarian measures, and ultimately futile even with them. Of course we can limit the flows of legal and illegal immigrants to the US. But to keep capital from flowing out of the US and toward countries with a competitive advantage in low-cost labor, we’d have to stifle and criminalize the very economic activities in which we do have a competitive advantage.

We lead the world in technological innovation. And the fact is, this is an elite pursuit. Only those who fall on the outer-edge of the Bell Curve in intelligence can fully participate in it. And given this, I genuinely don’t know whether a large and thriving middle-class can come back.

In this sense, even though I’ve personally joined the ranks of economically terrified Americans, I agree, intellectually, with our monied elites. (Marxists would say I’m suffering from false consciousness. But I’m not a Marxist. I’m just someone who has concluded that you can only suppress capitalism by trampling on liberty, and that the effort will anyway be doomed to fail.)

Enter some ideas about globalization that might be worth discussing here.

Dani Rodrik is a Turkish-born economist whose work I discovered because he was, at the time, writing about politics in Turkey in a more truthful way than most Americans seemed to be. He had a personal reason to do so: His father-in-law was ensnared in the Balyoz show trial, one of the more horrifying events I personally saw in Turkey. Because I respected his writing about the country I was living in, I started reading his work in economics.

I confess that at the time, I didn’t find them particularly compelling. But since the beginning of the Eurozone crisis, and in light of the way this election campaign has been developing, I’m beginning to think his Big Idea — the trilemma of globalization — has been vindicated.

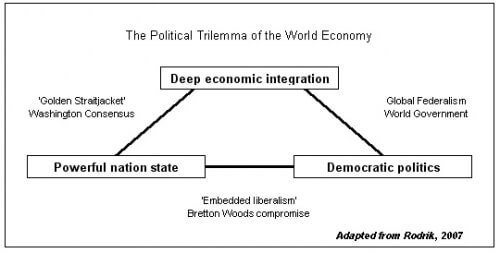

You can read The Globalization Paradox here; and if you don’t have the time, you can read an article here in which he simplifies it nicely. In brief, he posits an “impossibility theorem” for the global economy: “Democracy, national sovereignty and global economic integration are mutually incompatible: we can combine any two of the three, but never have all three simultaneously and in full.”

He sums it up with this illustration:

“To see why this makes sense,” he writes,

note that deep economic integration requires that we eliminate all transaction costs traders and financiers face in their cross-border dealings. Nation-states are a fundamental source of such transaction costs. They generate sovereign risk, create regulatory discontinuities at the border, prevent global regulation and supervision of financial intermediaries, and render a global lender of last resort a hopeless dream. The malfunctioning of the global financial system is intimately linked with these specific transaction costs.

So what do we do?

One option is to go for global federalism, where we align the scope of (democratic) politics with the scope of global markets. Realistically, though, this is something that cannot be done at a global scale. It is pretty difficult to achieve even among a relatively like-minded and similar countries, as the experience of the EU demonstrates.

Another option is maintain the nation state, but to make it responsive only to the needs of the international economy. This would be a state that would pursue global economic integration at the expense of other domestic objectives. The nineteenth century gold standard provides a historical example of this kind of a state. The collapse of the Argentine convertibility experiment of the 1990s provides a contemporary illustration of its inherent incompatibility with democracy.

Finally, we can downgrade our ambitions with respect to how much international economic integration we can (or should) achieve. So we go for a limited version of globalization, which is what the post-war Bretton Woods regime was about (with its capital controls and limited trade liberalization). It has unfortunately become a victim of its own success. We have forgotten the compromise embedded in that system, and which was the source of its success.

So I maintain that any reform of the international economic system must face up to this trilemma. If we want more globalization, we must either give up some democracy or some national sovereignty. Pretending that we can have all three simultaneously leaves us in an unstable no-man’s land.

I’m wondering if this idea, more than the idea of class war, could be a useful tool in trying to understand what’s at the heart of the so-called elite-base schism.

I’ve even been thinking, lately, that the idea might be applied to foreign policy and national security, as well. We can be a global hegemon — the so-called world’s policeman — at huge cost to ourselves. Or we can form alliances with countries that share some part of the burden. Try looking at the diagram above, but exchanging “guarantor of global order” with “powerful nation state.” Exchange “deep economic integration” with “regional military alliances.” Keep “democratic politics” in the same place. NATO and other regional defense pacts could be seen, perhaps, as analogues to the Washington Consensus. If we share the burden of global security with allies — deep military and political integration — it necessarily means a reduction in our sovereignty. If we don’t, we bear an unfair burden.

I don’t believe the globalization genie can be put back in the bottle, economically or militarily. We live in an age of ICBMs, nuclear weapons, biological and chemical weapons, and cyber warfare. If we retreat from the hegemonic role that brought the Pax America, it means losing our sovereignty in matters of national security and praying that the rest of the world may be trusted to do us no harm. If we want our allies to “pull their weight,” however, and minimize the burden on us, we have to accept that our allies will not be as concerned with our security — or our values — as we are, nor as competent at securing it.

Democracies being what they are, all of our politicians (in both parties) are now assuring us that they have what it takes to “keep us safe,” and that they know how to offload this defense burden onto our “allies.” The place where they lie — everyone one of them — in selling this plan is in failing to stress the implications of expecting “allies” like Saudi Arabia to act in our interests.

I don’t trust the Saudis to put my national security at the top of its agenda. Why should I? Nor do I want to pay for a huge and wasteful military. Why should I? Nor do I want to sacrifice American lives. Why should I? Who would? To what voter would any of that sound appealing? Not many.

So our politicians campaign on foreign policy lies, fantasies, and fairy tales. To be elected, it seems, you have to lie about foreign policy — because the truth is not what voters want it to be. This pushes much of the conduct of our foreign policy underground, into the realm of secrecy, where voters can neither see it nor appraise it. They wouldn’t vote for it if politicians spoke the truth about it. And this is, fundamentally, undemocratic.

I see the trilemma at work here, too: We can only have two out of three.

I doubt this idea explains everything. Perhaps it doesn’t explain much at all. No one theory about the workings of politics does.

But I thought I’d run it up the Ricochet flagpole and see what salutes. What do you think?

Published in Domestic Policy, Economics, Foreign Policy, General, Immigration, Military

Eh, not exactly. That tech is extremely portable. It also doesn’t create jobs. In fact, while automation in general will bring back a lot of US manufacturing, it won’t create that many jobs.

I can speak to electronics directly as that is my business. 1 skilled employee on 1 shift can do today what it took a dozen people to do in the 90s. In fact, my SMT line does exactly that. I’ve got 1 guy on it. I may need to add a second shift, but that would be just 1 additional job, plus 1 supervisor.

I could also invest more capital in more and better equipment to just make my line faster, and still just 1 skilled operator would be needed (plus maybe an assistant to feed parts to the line).

Theoretically, yes. The cost of labor isn’t the only issue, of course.

Here is another way to consider things:

If I need to add capacity or capability, I can do one of three things: throw labor at it, throw machinery at it, or outsource it. What is the least risky? Which has the best return? Our tax structure, labor regs, enviro regs, and investment regs all skew things away from adding people.

Is this true for every endeavor? Is it easy for every business endeavor to figure out which option is appropriate?

It’s not an easy thing to figure out. We always have to ask ourselves some questions:

So, it’s quite a puzzle.

Spare us more diatribes from Coulter, please.

I don’t think he is saying that the issues with the American middle class are positive. He is saying that there’s no decline in manufacturing output, the decline in jobs is due to productivity gains. This has been with us forever, since the Sabots tried to prevent the industrial revolution.

Middle class jobs were things like hand-wiring TVs in Indiana, instead of today’s cheap, reliable, one-chip flat screens that use astonishingly little power. The only person who would say that that was better is the person who was really good at hand-wiring electronics in the 1960’s.

The answer for all is not to turn back the clock and eliminate productivity improvements- it is to find new ways to add value to life and monetize those ways. We may have to give up the ideas we once had about where we each wanted our own place in this society to be- Claire wanted to make money as a writer; for whatever reason, that may not be in the cards, despite the three Claire Berlinski books I have on my own library shelf. I’ve been in school almost constantly for the last 40 years, in four different industries.

Zeihan claims that the US is uniquely situated for 3D printing because that technology is very energy intensive and we have unique access to cheap energy with natural gas fracking making NG super cheap. Hence portability doesn’t militate against domestic predominance of the use of 3DP. But there may be massive job dislocation coming. He notes that the world shipping industry will tank (so jobs in that sector will go away).

It may be as you suggest that the impact of this technology will be more in the same creative destruction category. But I don’t know. You will have to generate reams of new 3d software models, so it may be that labor shifts there from the transportation pool in the future. Too hard to predict.

For your one application, true, Skipsul. But the payoff is not one application, it is the ways to use the technology that no ione has yet dreamed of, and the fact that flexible, fast response prototyping and one-of-a-kind products are becoming reality in many cases. When I first got involved with factories, the key to bringing down costs and improving quality was volume. That is still the case for rigid, high volume designs, like iPhones.

But I would posit that a lot- maybe most- of the market growth in the future will not be in rigid, high volume (China-built) designs any more than the improvements in medical care coming from yet more $billion drugs that can be applied in the same way and dosing to large numbers of people.

I do too. I found a lot of value in reading him.

Claire I think this is a false alternative. I think that A) anyone who thinks that any European state, for instance, would pose a threat to us by increasing their own capability to defend themselves is looking at Europe through the prism of the past and not accounting for the sentiments of the current populace. I don’t think Europeans would stomach attacking one another a la WWII much less us. Just look at how they have reacted to Putin going into Ukraine. Unless you know something that I don’t know, there really hasn’t been much of a military response by anyone but us, maybe Poland.

Asia might be a little different, obviously, but we could reposition our force projection if Europe got back into the high politics game instead of chasing the ghost of “climate change.”

It will be. And it’s not just printing, but in all forms of metal fabrication. CNC has been predominant for a loooonnngggg time, but it’s just getting cheaper. Additive manufacturing in plastics is not energy intensive, but it is in metal. But both are slow, so limited to low volume and specialized processes. Zeihan may not appreciate this. High volume subtractive (milling, molding, stamping, forming, etc.) manufacturing, however, is energy intensive, and the capital equipment for that is coming down in price all the time. But, as per electronics, you don’t need a lot of people to run it. Not a lot of jobs coming there, even if the capacity here in the US increases 10 fold.

Again, been going on since anonymous came out with Autocad, and everyone in manufacturing already does that (been doing it since the 90s). Good skill to have, but those skilled in that area already displaced the old draftsmen. The software keeps getting better, so fewer people are needed to do it.

Yes, and Renewable Mandates, war on coal (AKA – electricity generation), staple power & power quality, general taxes & regulation, leach away many of our competitive advantages. Burdens China, and India aren’t subject to.

Very interesting discussion –

We live in an era of slow growth. That’s why people are anxious.

Globalization and automation have been around for a long time, and people’s jobs becoming obsolete is nothing new. I was working in the defense industry when the cold war ended. I know something about becoming obsolete.

During the high growth 80’s and 90’s, obsolete jobs were replaced. In the slow growth era we live in today, not so much.

So what changed? Not globalization and automation; they have been constants.

The change was in economic policy, starting in the White House. GWB brought us the biggest expansion of government since the Johnson years and tried to pay for it by weakening the dollar.

Then Obama came along and amplified Bush’s mistakes. The results speak for themselves.

In analyzing today’s mess, we should look at what changed, not what stayed the same.

What changed was the rate of government growth and the loss of a sound dollar.

The fix is simple but not easy. The first step would be to stop blaming the wrong things.

Accidental double post.

Again, what of economics? Whenever we have a balance of payments problem, usually the currency exchange rate compensates making US exports cheaper. Also, the tried-and-true principal of Comparative Advantage may be what drives production overseas also. That principle shows that both countries net gain. We need a professional economist to inveigh here, otherwise we just engage in pop-economics.

From 1997 to 2014, manufacturing went from 1.4 trillion dollars to 2.1 trillion. That’s an annual growth rate of 2.2%; it’s not great, but it’s not terrible, either; it beats inflation, for instance. We constantly get stories about how gloomy things because those sell well and because they’re valuable to the manufacturers, who are on the lookout for subsidies.

Almost any point I enter this thread, and there is much discussion here on jobs, job creation, creative destruction, and middle class survival, the immediate need I sense is to get government out of the picture. We have too much and it feeds itself and grows and things get worse from the perspective of those who cherish freedom. Deep economic globalization is a killer. We are still hanging on to our national sovereignty against every attempt by the Progressives to relinquish it. Remember, Barack Obama is a citizen of the World!

Guaranteed if we don’t turn back the governing trend, we are done.

Claire, thanks for this post and all plaudits are well-deserved.

Anyone here find something to like about Chesterton’s economic distributism concepts and the Catholic Church’s principle of subsidiarity? I have always favored free market economics but something akin to the above is what I like. At the same time, I see wealth gravitating to the largest and most politically powerful spaces in our current capitalist operating environment (and it is not based on free market economics). And it is not growing to produce a better outcome for mankind and functioning on self-interest exchange economic principles, but simply wealth-producing for the capitalist by reducing or eliminating all competitive alternatives. I have a notion that if we could somehow break-up the federal government’s lockstep dance with entities large enough to have gained almost complete control of our economic decision-making, we could at least have choices about what kind of marketplace we want to support. I recognize that there are instances where greater size works to the advantage of all. But don’t we have many situations in our economy where greater economic domination in cooperation with the federal government reduces freedom and hurts the people? Just a thought.

I’m posing it as two extremes, of course. No, I don’t think we’ll ever see a conventional war between France and Germany again, and yes, I do think it’s reasonable to expect them to contribute more to the NATO budget. (And Canada is a complete freeloader, spending-wise — why this is never a sore point between Americans and Canadians, I don’t know.) I was thinking much more of our alliances with, e.g., the Saudis, Turks, Jordanians, etc.

If you get government out of the picture (foreign governments as well as our own), then you get deeper economic globalization. “National sovereignty” is government power. It’s oxymoronic to want more national sovereignty activity and less national government.

Depends on how and where they are applied / allowed.

3D printing is terribly slow and is only economical for low volume production. High volume production will still be dominated by traditional manufacturing techniques.

Our local plastics manufacturer will build simple molds for less than $1000 and then sell you a lot of 500 for less than a buck a piece (depending on size).

The same economy of scale is there for metals components too.

3D printing is excellent for prototyping, very low volume production, and things that would be very difficult to do in other ways.

One can want different kinds of big government and be against globalization, sure, but one really can’t be against government in general and also opposed to free markets.

This is probably the clearest finding in polls about who they are.

James, I never said more national sovereignty and less national government. We should keep the national sovereignty delegated to the federal government in the US Constitution, no more, no less, in lieu of yielding that limited sovereignty to world power and we should yield back to the states and the people sovereignty that has been usurped by our federal, not national, government. Disagree, if you choose, and say what is deficient in that notion, but it’s how I read the Constitution. If free market principles are incompatible with maintaining a free and sovereign United States, then maybe we have to consider some alternatives.

That’s now, in the infancy of 3D printing. 20 years down the road?

No it isn’t.

At one time the United States had a government that was almost non-existent internally, yet enforced import duties and derived a great portion of its revenue from that source.

As that United States has gradually been smeared out of existence, we get a government that grows ever more intrusive internally yet sees lees and less of a difference between an American citizen and a foreigner.

I would very much prefer a government that levied tariffs yet left me alone, rather than the one we have now, which strives to eliminate tariffs yet wants to record every phone call and read every email.

Conservative also means suspicious of change. Most peasantries are the most suspicious of change because change typically works out poorly for them, and meaningfully so.