Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

What Is Omnipotence?

What Is Omnipotence?

I remember hearing some variation of “Can G-d make a rock so heavy He can’t move it?” in high school. I don’t remember thinking much about it at the time. My earliest memory of having any clear thought about it is probably around 2010 when, as I recall, I answered it “Yes, and that rock is called ‘free will.'”

Which brings us to one thing normally recognized by contemporary philosophers as a reasonable limitation on omnipotence: G-d does not have the ability to break the rules of logic. That’s part of how Christian philosopher Alvin Plantinga responds to atheist philosopher J. L. Mackie. In a nutshell, Mackie wonders why G-d can’t just make a perfect world with free people in it, and Plantinga replies that even omnipotence doesn’t have the power to give us freedom and force us to do the right thing at the same time.

That’s a step in the right direction, but it doesn’t clear up quite enough. Some people seem to think omnipotence means being able to do just anything. That is incorrect. Omnipotence means having unlimited power. That’s the dictionary definition.

Now it’s true that “power” can mean an ability–the power to win a race, the power to eat candy, the power to watch television like Ratbert here:

But “power,” more fundamentally, means might or strength. “Power” can mean an ability because more power often means you can do more things.

But sometimes more power means there are things you can’t do. A powerful runner has a diminished ability to lose a race while trying to win; the most powerful runner possible wouldn’t be able to do it at all.

When I’m navigating the Hong Kong MTR system and have to switch from the East Rail Line to the Kwun Tong Line, I could hardly be the last person to hike that quarter-mile through the bowels of Kowloon Tong Station even if I tried. That’s not because I have some weakness relative to whoever comes in last; it’s because I don’t.

Superman does not have the ability to be killed by a bullet when there’s no kryptonite nearby; that lack of an ability does not mean he has a weakness; it means he has extra power.

And that brings us to the tradition. Omnipotence is an attribute traditionally ascribed to G-d by a tradition, and that tradition is classical theism.

What the word “omnipotence” means is, above all, what the traditional doctrine teaches. Similarly, the term “the Trinity” means G-d according to the doctrine of orthodox Christianity–One G-d, Three distinct Persons who are G-d. Heaven knows how many people out there think “the Trinity” means one G-d with three different roles. Their confusion does not change the meaning of a term that denotes the teaching of a tradition.

What classical theism teaches about omnipotence is that G-d has unlimited power, not that he can do just anything.

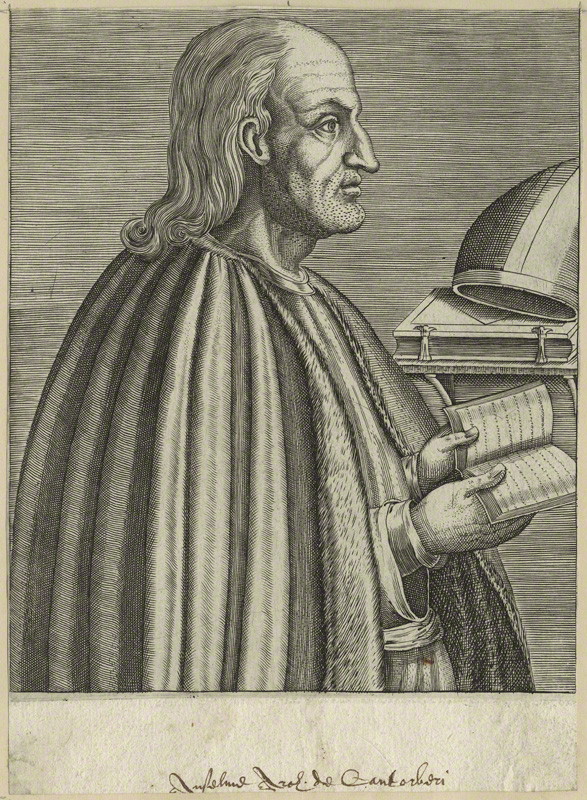

People representing the tradition–like Aquinas, and like Anselm here–also explain that certain abilities are weaknesses, not strengths. E.g., the abilities to sin, lie, die, or break the rules of logic.

Being able to do things like that is not required by omnipotence. Being unable to do them is.

Anselm’s book Proslogion introduces the general idea very well, and it’s not a hard book to read (if you don’t get bogged down in the ontological argument in chapters 2 and 3). Here’s chapter 7, where Anselm explains omnipotence, and here’s my short YouTube intro to this lovely little book.

And now . . . surprise! Once we have that perspective in place, we can actually go back to that other sense of the term that caused all this trouble in the first place–“omnipotence” as the ability to do anything.

People like Anselm and Aquinas will actually welcome that definition of omnipotence–but only as long as we understand what it actually means to do something. Sinning is not in itself the doing of a thing. It’s a way of failing to do right. Lying is not a thing you do. It’s a particular way of failing to do something–to speak the truth. Dying isn’t a thing you do; it’s just a failure to keep living. Breaking the rules of logic is not a thing you do, but a particular way of failing to do a thing–to keep the rules.

Technically, an ability to do something means an ability to do a real thing–and these aren’t even real things. And, again, being able to do these things is not some limit on omnipotence; it’s actually part of what omnipotence is. (For example, see Aquinas’ Reply to Objection 2 here.)

Or so the tradition says.

And as for the overrated rock question, if you wanna take it as some sort of metaphor for free will like I once did, be my guest and answer “Yes.”

But if you want to take the question literally and apply a dictionary definition or the equivalent historical definition of omnipotence to it, then the answer is “No”: An omnipotent G-d could not have a weakness. But if G-d made Enchanted Rock in west Texas so heavy that He didn’t have the power to move it, then he would have a weakness.

But trying to think with the tradition is hard work if you’re not used to it. So here’s a suggestion:

Try to forget about the tradition for a moment, and just suppose a few simple principles:

–G-d does not have the ability to break the rules of logic,

–to have an imperfection is to have a limitation,

–and to have a limitation is to have a weakness.

Now let’s admit that a loser like me might, constrained by extreme circumstances, have a moral obligation to lie once in a lifetime. But an omnipotent being will never be constrained by such circumstances; G-d is not a loser like me. So consider this argument:

1. To tell a lie when one is not constrained by extreme circumstances is to have an imperfection.

2. To have an imperfection is to have a weakness.

3. Therefore, to tell a lie when one is not constrained by extreme circumstances is to have a weakness.

You can add one premise and extend the argument.

3. To tell a lie when one is not constrained by extreme circumstances is to have a weakness.

4. It is not possible for an omnipotent being to have weaknesses.

5. Therefore, it is not possible for an omnipotent being to tell a lie when not constrained by extreme circumstances.

If omnipotence means an omnipotent G-d should be able to tell a lie, which of those premises is wrong? Is it 1, 2, or 4?

Published in General

When is that going to be the case without being constrained by circumstances?

The movie with Jimmy Stewart.

Thanks.

It was a hypothetical. Let me make that explicit:

If, hypothetically, God decided that the outcome he desired would best be achieved through deception, would his use of deception still be wrong?

This looks to me like a “loaded question fallacy,” as some logic textbooks call it–a question that assumes things it should not assume.

If you want to ask me this about Zeus, I think I can answer that.

If you want to ask me this about a G-d I think is omnipotent, I don’t know how I can even answer; you might as well ask me whether I liked the unicorn exhibit at the zoo, or how many angles there are in a square circle.

How is it possible that deception could be the best means to the desired end for a being who is not constrained by circumstances?

Yes, it’s hard to imagine the choices God faces and how he might choose to deal with them.

For example, we know that some infants suffer terribly and then die. Based on your reasoning, we have to believe that God desired this particular outcome despite choices that would have let him prevent it. We can’t assert that God chose this because there were no “better” options that would have achieved his desired outcome, if we assert that an omnipotent God always has other choices.

Then we have to wonder why God chooses such seemingly unfortunate outcomes despite his ability to avoid them.

Whatever do you imagine gave you such insight?

You are not disbelieving in God, you are auditioning.

Next.

It has been said that God did not reveal the means of salvation to anyone prior to Jesus’ crucifixion. Not even the angels in Heaven, who longed to look into it (1 Peter 1:10-12). So even satan would not have known that Jesus’ death would free all mankind from the punishment for sin. The suggestion is that satan would not have led Jesus to be crucified if he had known.

God did not lie about His plan, but merely didn’t reveal it. This could be called by humans deception, or encouraging self-deception. Was it wrong?

No, I’m not auditioning. I’m trying to understand. If you find my questions offensive go somewhere else.

Assertions are being made about what God can and can’t do, and I’m trying to understand the basis for those assertions.

(a) I’m told that God can’t lie.

(b) I’m told that God always has other choices that will achieve the best possible outcome without lying, because God is omnipotent.

(c) I know that suffering occurs, and it follows that an omnipotent God could prevent that but chooses not to.

(d) My understanding of the resolution of that dilemma has always been that the suffering occurs within a greater context, and is part of God’s plan.

(e) But it seems to me that the assertion in (b), if true, must also obviate the need for (c): that God could achieve his plan without the suffering if he chose to, because God is omnipotent.

And I don’t understand why allowing unnecessary suffering is consistent with God’s perfection, once we exclude the possibility that it is the best way to achieve God’s desired end.

No, no, no. You’re misreading me dreadfully.

Your writing is unclear, but not unclear enough that I can’t be pretty optimistic about this:

You are trying to talk with about omnipotence.

I got that much right, didn’t I?

But that means I don’t have to imagine anything. I just have to observe that an omnipotent being is not constrained by circumstances to the degree that it is even plausible that deception could be the best means to the desired end.

I wonder what reasoning you think I’m using. This doesn’t sound like it has much to do with any reasoning I’ve used here.

Do you understand that you are now changing the subject? Now you’re trying to talk about the problem of evil. That’s fine, and it even has some connection to the opening post. But it’s a heckuva change of topic.

No, I find them inane.

I’d sooner say permitting self-deception. But you have a real insight here, and it is more than enough to provide an adequate response to an objection I can see. This objection is the best I can do to make sense of what I can speculate HR might be trying to get at:

Imagine a scenario in which an omnipotent G-d is constrained by human free will to such a degree that his least-bad option is to deceive!

I don’t even know how to imagine this scenario. If human free will has left G-d no good options, then whatever scenario we are being asked to imagine must be rife with extreme sin. If deception is needed to mitigate some harm, it seems a virtual certainty that an omnipotent and omniscient G-d would be able to find a way to allow the extremely sinful humans to deceive themselves just as much as they need.

Henry, if you would understand rather than proclaim your moral superiority, read Job, chapters 38-41. Answer all the questions and get back to me.

Think of it as a try-out.

The main point in the opening post and in this thread has been only this:

A secondary point is to zoom in on an interesting argument that an omnipotent being cannot tell a lie. Most recently, we seem to be bogged down in Premise 1 of that argument.

Good job! This is better.

Better, but still mistaken:

(c) is an inevitable consequence of G-d giving us significant responsibility and free will and our misusing that free will and abusing that responsibility. (c) is true because of what we do. (b) is about what G-d can do. It doesn’t overrule (c).

Percival, I’ve read it. I’ve even taught it, back when I taught Bible study in our church.

So tell me:

Why does God allow people to suffer? It can’t be because he has no better choices: Augy has assured us that God always has other choices. So why? Does God want the suffering? What other reason might there be?

Educate me.

You taught it, but you don’t seem to have understood what it meant.

I have assured you of nothing of the sort.

Inevitable?

Does God not have choices that wouldn’t result in that suffering?

Note the correct bolding.

Yes, inevitable.

No, no other choices–if we misuse our free will and abuse our responsibility.

Okay, I’m trying to be perfectly open and non-confrontational here. I sincerely want to understand the argument you’re trying to make, and to reconcile it with my own thoughts. Please read this in that spirit.

(a) Bad things happen.

(b) God allows those bad things to happen either because he can’t prevent it, or because he can prevent it but chooses not to prevent it.

(b1) If God can’t prevent those bad things from happening, then the implication is that God is constrained in some sense.

(b2) If God can prevent those bad things from happening but chooses not to, then it seems one of two things must be the case:

(b2.1) either allowing those bad things to happen results in a better result than any other course of action, or

(b2.2) God simply chooses to let bad things happen despite there being no necessity or advantage to allowing it.

So help me reconcile all that, or show me where I’m assuming something that you don’t believe is true.

Regarding (a): Do bad things happen? Is it somehow possible that those things we think are bad are actually not in and of themselves bad?

Regarding (b1): If God can’t prevent it, then he is constrained. But I am told that God is not constrained. (constraint)

Regarding (b2.1): If the best way God can find to achieve a particular outcome is to allow suffering, then that suggests that God is constrained in his choices. Otherwise he would find a better way to achieve the desired outcome. (constraint)

Regarding (b2.2) Unless God would prefer the suffering to occur despite better options existing. I find this difficult to reconcile with any reasonable concept of “perfection.” (challenging sense of “perfect”)

So there I am. In as few words as practical: what am I missing?

“What if God, although willing to demonstrate His wrath and to make His power known, endured with great patience objects of wrath prepared for destruction? And He did so to make known the riches of His glory upon objects of mercy, which He prepared beforehand for glory…” (Romans 9:22-23)

I take it as a given that God is Love, and Truth, and is Just, and Glorious, and Good, and Patient, and Merciful, and His Judgment is right, and God works all things to the good of those who are called according to His purpose. Off the top of my head, God also can be Jealous of all who make claim to other false gods, and Wrathful to those who sin (or who commit spiritual crime, or spiritual lawlessness) and who do not change their ways.

(Continued next comment)

(continued)

I have already said before on other posts, that God looking from outside time, had I suppose infinite choices for exactly of what the universe would be constituted and what would happen within it. His purpose was to demonstrate Himself to a universe of beings that didn’t innately know or understand Him.

Satan rebelled against God essentially intending be an alternative god to God, or to take God’s place. The Lake of Fire (not Hell) was prepared as punishment for satan and his angels. It has been suggested that when satan rebelled, other angels who did not rebel did not understand the ramifications of sin and rebellion and of acting outside God’s character, and said wonderingly amongst themselves: Eternal fire! Isn’t that a bit much?

And so I believe that God wanted to demonstrate to the universe just how bad and corrupting and evil any sin ultimately is. And God has allowed satan to do his worst, within certain confines, ending with satan’s attempt to destroy all humanity both spiritually and physically – an end that he will not achieve. And we have seen this warring and murder, and illness and psychopathy (both personal and societal) throughout history. And it continues to today. God has allowed this, I believe, to make an everlasting point: all sin no matter how small, if unchecked, leads to death and destruction: from thorns and thistles, to violent and poisonous creatures, to corrupting the human genome to something not fully human, to birth defects, to famine, pestilence, and potential nuclear war.

God will make everything right in the end. This I believe as surely as I believe that God exists. This ultimately will be cured according to God’s Mercy and his Justice, and His cleansing and fixing forever the body and soul of Man. And every tear will be wiped away, and the suffering we all go through, some worse than others, will be eternally rewarded with a life that we can’t even imagine right now. Even the universe will be rolled up and burnt, and replaced with a new and perfect one.

But it’s God’s universe, and what is one who disagrees with God to do? Have one’s own courts? Have one’s own resurrection? Create one’s own Heaven on earth? Make one’s own New Man?

Others will certainly disagree with me, and I will listen to them. But for now, this is what I consider to be the reality of God’s continuing Creation.

Then you need to choose which argument you’re talking about: the one in # 104 (summarizing the opening post as a whole), or the one about the ability to lie (at the end of the opening post).

The next step is to just read the argument. The premises and conclusions are numbered to make it simpler.

I honestly do not understand what else you would need to do after that in order to understand it.

(Well, maybe your brain is having trouble processing the words of one of the premises; that happens to me sometimes! If that’s the problem, you should probably start by telling me which premise it is.)

G-d can’t prevent it without also preventing us from having free will and significant responsibility. But what we opted to do with our free will and responsibility was our fault, not G-d’s.

At most, G-d is only constrained by logic, as indicated in the second paragraph of the opening post. (But I wouldn’t even categorize this as a constraint on G-d as such; see # 55.)

I think it’s that. Free will is either itself a good outweighing a whole lot of evil, or is a necessary condition for some other greater good. Maybe both. (And maybe there are some other reasons, too!)

So far, you’re doing pretty well.

Yes, they happen.

Nothing much that I can see. The problem isn’t what you’re missing. The problem is what you’re adding. Specifically, it looks to me like you’re imagining some connection to a different topic: You’re assuming that this somehow changes G-d’s ability to find a way to do good without lying.

The only “constraint” here–not that I would even call it that–is G-d’s inability to give us free will and take it away at the same time. That has no bearing on whether G-d would ever be constrained in such a way as to have no better option than lying.

G-d can’t stop us from causing suffering with our free will, but that’s just what free will is. That’s because of what we choose to do. This simply has no relevance to the ability of an omnipotent being to avoid the need to lie.

Just wanted to throw in a Torah-centric view.

1: Yes, G-d CAN lie. He even tells Moses to do it, repeatedly. The deception is planned and divinely-ordered. It is in black and white.

2: G-d DOES limit Himself. That is how the world – and people – exist. In this world, G-d is not omnipotent. That is presumably a choice He made, when he allowed the world to exist.

3: Within this world, G-d is NOT out of time, or perfect or unchanging. In the Torah, G-d is an actor, surprised by what mankind chooses to do, inspired by man’s own choices, sometimes imitating what Man has pioneered (Noah, sacrifices, Jacob, booths, etc.). G-d changes because He changes His mind.

4: Mankind are responsible. G-d is not in nature – he is only in US. So we are to be his partners and agents in making the world better.

In general, I am always surprised how much of standard Christian theology is really Greek in the sense of making words like “Truth” and “Logic” and “Perfect” deities in their own right. These words do not exist with those meanings in the Torah. They are Greek inventions that corrupted Judaism, and may well have done some damage to Christianity as well.

Well, you’re not really challenging the traditional or dictionary definition of omnipotence so much as rejecting the doctrine. I figured you would.

All interesting claims to, perhaps, take up another day.

That is accurate. Words can mean many things, including fantastical or impossible things. I don’t see support for the primacy of these words (doctrine) in the Torah at all.

Your reply relies on God’s desire to grant us free will. But my comment makes not reference to free will. Lots of bad things happen that have nothing to do with our choices. Children are born deformed, people die of terrible diseases, natural disasters happen. There is a lot of suffering that isn’t the product of free will.

So can you go back and respond to my comment #110 again, this time without invoking God’s desire to preserve our free will, since that isn’t a part of my argument?

Ok, maybe I will take up some of this. It is, after all, another day now.

On the other hand, something else just came up on Ricochet that fills me with foreboding. So I’ll just take the easiest one out of four for now. (I’ll keep a draft reply to the other three around just in case things go well.)

Yes.

iWe, I appreciate that there are different conceptions of God. I have little interest in the theology. My interest is only in understanding the rationale behind the assertion that a being can be simultaneously omnipotent and incapable of lying.