Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

What Is Omnipotence?

What Is Omnipotence?

I remember hearing some variation of “Can G-d make a rock so heavy He can’t move it?” in high school. I don’t remember thinking much about it at the time. My earliest memory of having any clear thought about it is probably around 2010 when, as I recall, I answered it “Yes, and that rock is called ‘free will.'”

Which brings us to one thing normally recognized by contemporary philosophers as a reasonable limitation on omnipotence: G-d does not have the ability to break the rules of logic. That’s part of how Christian philosopher Alvin Plantinga responds to atheist philosopher J. L. Mackie. In a nutshell, Mackie wonders why G-d can’t just make a perfect world with free people in it, and Plantinga replies that even omnipotence doesn’t have the power to give us freedom and force us to do the right thing at the same time.

That’s a step in the right direction, but it doesn’t clear up quite enough. Some people seem to think omnipotence means being able to do just anything. That is incorrect. Omnipotence means having unlimited power. That’s the dictionary definition.

Now it’s true that “power” can mean an ability–the power to win a race, the power to eat candy, the power to watch television like Ratbert here:

But “power,” more fundamentally, means might or strength. “Power” can mean an ability because more power often means you can do more things.

But sometimes more power means there are things you can’t do. A powerful runner has a diminished ability to lose a race while trying to win; the most powerful runner possible wouldn’t be able to do it at all.

When I’m navigating the Hong Kong MTR system and have to switch from the East Rail Line to the Kwun Tong Line, I could hardly be the last person to hike that quarter-mile through the bowels of Kowloon Tong Station even if I tried. That’s not because I have some weakness relative to whoever comes in last; it’s because I don’t.

Superman does not have the ability to be killed by a bullet when there’s no kryptonite nearby; that lack of an ability does not mean he has a weakness; it means he has extra power.

And that brings us to the tradition. Omnipotence is an attribute traditionally ascribed to G-d by a tradition, and that tradition is classical theism.

What the word “omnipotence” means is, above all, what the traditional doctrine teaches. Similarly, the term “the Trinity” means G-d according to the doctrine of orthodox Christianity–One G-d, Three distinct Persons who are G-d. Heaven knows how many people out there think “the Trinity” means one G-d with three different roles. Their confusion does not change the meaning of a term that denotes the teaching of a tradition.

What classical theism teaches about omnipotence is that G-d has unlimited power, not that he can do just anything.

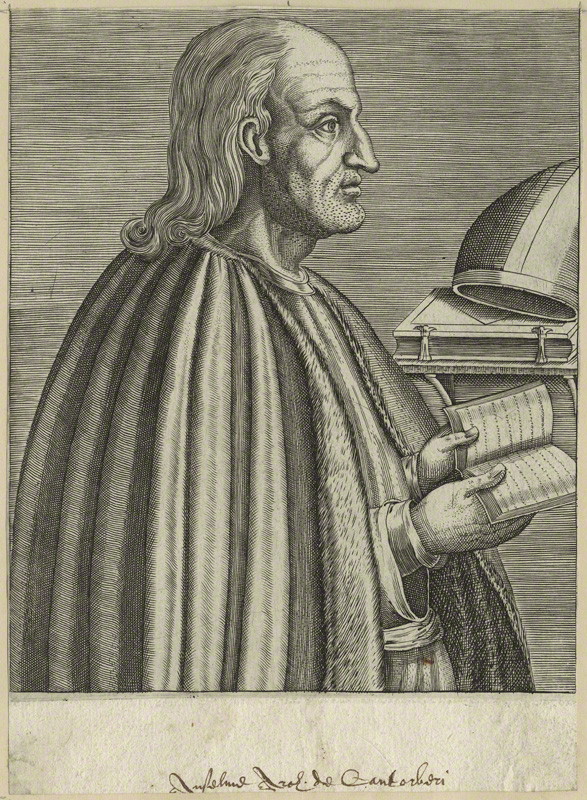

People representing the tradition–like Aquinas, and like Anselm here–also explain that certain abilities are weaknesses, not strengths. E.g., the abilities to sin, lie, die, or break the rules of logic.

Being able to do things like that is not required by omnipotence. Being unable to do them is.

Anselm’s book Proslogion introduces the general idea very well, and it’s not a hard book to read (if you don’t get bogged down in the ontological argument in chapters 2 and 3). Here’s chapter 7, where Anselm explains omnipotence, and here’s my short YouTube intro to this lovely little book.

And now . . . surprise! Once we have that perspective in place, we can actually go back to that other sense of the term that caused all this trouble in the first place–“omnipotence” as the ability to do anything.

People like Anselm and Aquinas will actually welcome that definition of omnipotence–but only as long as we understand what it actually means to do something. Sinning is not in itself the doing of a thing. It’s a way of failing to do right. Lying is not a thing you do. It’s a particular way of failing to do something–to speak the truth. Dying isn’t a thing you do; it’s just a failure to keep living. Breaking the rules of logic is not a thing you do, but a particular way of failing to do a thing–to keep the rules.

Technically, an ability to do something means an ability to do a real thing–and these aren’t even real things. And, again, being able to do these things is not some limit on omnipotence; it’s actually part of what omnipotence is. (For example, see Aquinas’ Reply to Objection 2 here.)

Or so the tradition says.

And as for the overrated rock question, if you wanna take it as some sort of metaphor for free will like I once did, be my guest and answer “Yes.”

But if you want to take the question literally and apply a dictionary definition or the equivalent historical definition of omnipotence to it, then the answer is “No”: An omnipotent G-d could not have a weakness. But if G-d made Enchanted Rock in west Texas so heavy that He didn’t have the power to move it, then he would have a weakness.

But trying to think with the tradition is hard work if you’re not used to it. So here’s a suggestion:

Try to forget about the tradition for a moment, and just suppose a few simple principles:

–G-d does not have the ability to break the rules of logic,

–to have an imperfection is to have a limitation,

–and to have a limitation is to have a weakness.

Now let’s admit that a loser like me might, constrained by extreme circumstances, have a moral obligation to lie once in a lifetime. But an omnipotent being will never be constrained by such circumstances; G-d is not a loser like me. So consider this argument:

1. To tell a lie when one is not constrained by extreme circumstances is to have an imperfection.

2. To have an imperfection is to have a weakness.

3. Therefore, to tell a lie when one is not constrained by extreme circumstances is to have a weakness.

You can add one premise and extend the argument.

3. To tell a lie when one is not constrained by extreme circumstances is to have a weakness.

4. It is not possible for an omnipotent being to have weaknesses.

5. Therefore, it is not possible for an omnipotent being to tell a lie when not constrained by extreme circumstances.

If omnipotence means an omnipotent G-d should be able to tell a lie, which of those premises is wrong? Is it 1, 2, or 4?

Published in General

Thank you for the clarification.

You say “God can not prevent [all of] the harm caused by acts of free will without eliminating the free will in the process.”

Do we agree that God can prevent some of the harm caused by acts of free will without eliminating the free will in the process?

Well, yes. That, or something like that.

But I’d sooner say “redeem it” than “prevent it from ever having happened.”

Of course.

In that case, I have no dog in this fight, since G-d clearly tells Moses to lie. The belief that G-d cannot lie is counter-textual.

I would have thought that this much is simple and pretty uncontroversial:

A. Assuming we misuse our free will, a good and omnipotent G-d would lack the ability to prevent all evil without ending free will as well.

B. A good and omnipotent G-d would prevent some evil and would, eventually, fix things.

That’s just rudimentary deductive logic, isn’t it?

Of course, that leaves plenty of questions. Like whether it’s likely that the level of suffering we see now is too much for free will to be worth it. Or whether some of it is likely not the sort that can be traced to free will. I don’t have much to say about these other questions other than that they would necessarily require non-deductive reasoning in areas where human knowledge is severely limited–much like my kid who thinks it’s the end of the world when he suffers the loss of video game privileges.

And, to try to keep in mind the main point, any limitations on G-d we’re talking about here are merely the result of the impossibility of giving us free will and taking it away at the same time; any suffering G-d can’t prevent without also removing free will is caused by us creatures.

I don’t see how that has anything to do with whether an omnipotent being would be constrained by external circumstances in such a way as to be left with no better option than lying.

Ok, I guess I can try the other ones now.

Do you have some passage in mind in the Torah where G-d specifically lies–not Moses, not the midwives?

G-d telling Moses to lie and G-d lying himself are not the same thing. (I figure my plan to lie–in the link in the opening post–was the right thing to do, so of course I figure it’s what G-d would want me to do. But that has no relevance to whether G-d himself would lie.)

This doesn’t look like Torah interpretation. This looks like metaphysics–it looks like the theory that reality is structured such that if G-d creates people he must be limiting himself.

That was William James’ view–not the first time you two have said the same thing. It is also wrong. It’s a lousy theory in metaphysics–not the first time you’ve done that either.

G-d interacts with us, to be sure. The details of G-d’s interaction change from moment to moment, of course. That is what is in the Torah. From that, of course, it does not follow that G-d himself is changing.

Of course G-d is as the Scriptures present Him to be–and they present Him as the G-d who interacts with us and with our circumstances, both of which are changing. But from the premise “G-d interacts with changing things” the conclusion “G-d must also be changing” does not follow by any principle I have ever read in the Bible.

It does follow by certain fancy principles in philosophy. But I’ve never read those principles in the Bible.

So sometimes when God prevents the harm caused by acts of free will it eliminates the free will that caused the harm, and sometimes it does not.

What determines, in each instance, whether God’s intercession in a particular instance does or does not eliminate free will?

You keep trying to fit God into an analytical box small enough to fit in your finite mind.

What would be your next trick? Emptying the ocean with a teaspoon?

FYI, I think I’m going to start abbreviating sometimes: FW for “free will.”

G-d cannot prevent all harm caused by acts of FW without eliminating FW in the process. G-d can prevent some.

What makes the difference? I have no idea. The only point is that there is a difference.

Would I want my kids to be spared all the harm their friends might cause them through misuse of free will? Of course not: I want their friends to have free will. Would I spare my kids from some harm by helping them after their friends have hurt them? Yes, of course.

There’s more: I figure G-d does interfere with FW sometimes. When some instance of restricting FW can do more good than permitting it, G-d often restricts FW. (E.g., the death of Herod in the book of Acts.)

But when does that principle kick in–when does restricting FW do more good than letting it run wild? I have no idea. The only point is that sometimes it does.

I want the kids to have FW. If one is insistent on hitting the other in the head with a stick, of course I restrict her FW.

How do you know that God isn’t simply eliminating some free will when he intercedes in particular cases?

I just said that He does sometimes.

Ah. Your comment was ambiguous, and so I misunderstood. Let me clarify:

When you wrote:

Did you mean:

(a) G-d cannot prevent all harm caused by acts of FW without eliminating FW in the process. G-d can prevent some [harm caused by acts of free will without eliminating any free will in the process].

Or did you mean:

(b) G-d cannot prevent all harm caused by acts of FW without eliminating [all] FW in the process. G-d can prevent some [harm caused by acts of free will, eliminating some free will in the process].

Or is there another interpretation that I’m missing?

I meant that.

And then I added that in # 159.

So it doesn’t always eliminate free will when God prevents harm done by an exercise of free will.

If that’s the case, how do we know that God is limited in the amount of harm he can mitigate without eliminating free will?

Because that’s what responsibility + FW means. If we can’t freely choose and act and and have the consequences take place, then we don’t have freedom–or not as much of it anyways.

But I think you just said that sometimes we can. That is, you said that sometimes God can prevent the consequences without impairing our free will.

So how do we know that God can’t always prevent the consequences without impairing our free will?

By knowing what FW and responsibility are.

If there were no consequences for your choices, what would the meaning of free will be?

So, to summarize: God can eliminate some consequences without eliminating free will, but he has some constraint on the number or nature of the consequences he can eliminate without eliminating some or all free will. He can eliminate some; he can’t eliminate all. He is somehow constrained, though we don’t know precisely how.

Is that a fair summary?

Yes.

Except that, as noted a while back, I wouldn’t call it a constraint.

No, I suppose not.

So back to this free-will-and-consequences thing.

If a child is born with a terrible defect that ends its life at great discomfort, and if that defect was the direct result of a freak event, say a cosmic ray that tragically strikes the developing fetus at a critical moment, can we be confident that the suffering is the consequence of the exercise, by some human, of free will?

No.

We can be confident that it’s the result of the exercise of FW by some being. Not necessarily human.

Why would we believe that?

Scripture. Reason. Either or both. Same as believing anything else.

Have I missed some reason not to believe it?

Is every physical event the result of free will being exercised by someone or something?

No.

(Unless G-d used FW in creating the universe.)

How about on Eden… on that day you will surely die?

Or a promise to Avraham of 400 years? Nothing like it.

Or eating quails for a duration? The promise is not delivered.

I’m not certain, but I think the basic Christian theology on this is that human beings were originally to have a very different relationship with nature. But for the fall, the theory goes, we would have more complete knowledge and mastery of nature, and therefore the ability to easily prevent tragedies like the one you mention. Same with cancer and hurricane and viruses and volcanoes and hang-nails. We wouldn’t have had to trudge through thousands of years of scientific work to figure those things out.

Early on, human beings proved themselves morally incapable of having such power and such a relationship to God and nature. Christianity describes the process of restoring that relationship.

As for why the material universe contains such dangers in the first place, i.e, why would a loving God make a place dangerous for his people to live in, such that they would need mastery and knowledge of it, I think there are good answers out there. It’s been 20 years or so since I’ve read it, but CS Lewis’ The Problem of Pain addresses that question.

Basically, if there is to be a material universe at all – separate entities in a common plane of existence – the possibility of damage is logically inherent in such a universe.

Is every natural disaster, illness, and instance of suffering and pain the result of free will being exercised by someone or something?