Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

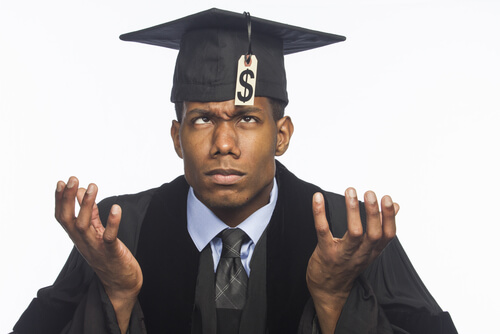

Majoring in Positive Thinking

Majoring in Positive Thinking

These days, you can go to college for just about anything and get the government to underwrite and subsidize your loan, to the tune of tens of thousands of dollars. As Megan McArdle writes, there’s a case to be made for some public financing of education:

These days, you can go to college for just about anything and get the government to underwrite and subsidize your loan, to the tune of tens of thousands of dollars. As Megan McArdle writes, there’s a case to be made for some public financing of education:

There is actually some economic logic to encouraging people to borrow money for school. Education is an investment in human capital, and expensive capital goods are often financed. Doing so makes everyone better off: The lender gets a tidy return, and because the borrowers increase their ability to make money, they can make their interest payments and still be richer than they would have been if they’d painstakingly saved up the money for 10 or 20 years before making the investment.

The problem isn’t that a liberal arts education is a bad idea, let alone one opposed to the public interest. If we stipulate that earning a liberal arts degree confers critical thinking and writing skills as well as a deeper understanding of one’s culture and history — as, indeed, some still do — then it’s trivially easy to see how that knowledge and those skills would benefit society at large, at least in the aggregate. In economic terms, there’s little question that a good liberal arts education has positive externalities.

Of course, if you say, “My education has positive effects on the public,” that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a good investment for the public to make. In order to determine that, we’d need to attempt to quantify those benefits (increased tax revenue, increased production, better civic decisions, etc.), and then balance them against the costs to society. If — to make some numbers up — a $100,000 BA brings a million dollars in benefit to the degree holder as well as $50,000 in indirect benefits to society, that makes it a great investment for the degree holder … but a lousy one for the public. It’s not that their interests are at odds, only that the degree-holder has more and the public less to gain from the same investment and, therefore, rightly assign a different value to it. Maybe it makes sense, from an economic standpoint, for the government to offer a smaller subsidy (say $25,000), but that’s not the way things are trending.

Back to McArdle:

But let’s get back to that public policy question. If someone proposed a program to help people be better citizens leading richer mental lives, you probably wouldn’t be prepared to spend billions of dollars on it, nor would you encourage individuals to take on crippling debt to pay for it.

The federal government now has $1 trillion worth of student loans in its portfolio, a substantial portion of which will be forgiven entirely or in part. But almost no one even dares to ask what we’re getting for all this money. The economic and social benefits of education are a political given, as axiomatic as mother-love or the speed of light. Periodically, people complain about the cost, and ask whether we’re getting value for our money — but how can we figure out the answer to that when we’re not even clear on what it is we’re supposed to be getting?

The fact is, some degrees have a both bigger and more easily quantified benefits to society than others and — putting aside the questions of whether it’s constitutional, or otherwise a good idea, for the government to subsidize education — it’s consequently much easier to make a case for at least some public subsidy of those degrees. As McArdle suggests however, $1 trillion in bad, below-market loans (and rising) seems like a lot of money for the benefits.

Of course, individual preferences don’t always match those of the public. Maybe I’d make a lousy engineer, wouldn’t enjoy it, or otherwise think it’s a bad choice for me. If I’m ultimately the one on the line for paying the bill, I get to make that determination. But to the ever-growing extent the public is picking up the tab, its interests will take priority and probably don’t match mine.

The more we involve government in financing our education, the more our educational choices will be steered by the government’s preferences, not ours. If we want to make our own decisions about our education, it’s in our interest to keep government at arm’s length.

Published in Culture, Domestic Policy, Economics, Education

Not to mention there is very little human capital gained from earning a degree in the aggregate. Most of the gains come from signalling that you are someone who was able to complete a degree. It rarely gives people useful skills that employers are interested in. So when the public pays for more people to have degrees, each of the degrees are worth slightly less since there are now more people with the same credentials. I’d be willing to bet that this effect eliminates most of the net benefits for society as a whole. In the end, when you pay for a degree you’ve made one person’s life better (who likely would have been able to do it anyway) at the expense of everyone else with that degree.

Why does the Federal government have to do it? States used to pick up a large fraction of the cost of university education for in-state students. Why can’t these sort of subsidy issues be handled at the state level?

Penn State…1978…engineering…$20,000 out of state tuition, room and board for a five year program. Earned $15,000 during the summers painting houses. Borrowed $1900 which I paid off at $32.28 per month.

Why don’t we go back and take a snapshot of what Penn State looked like back then and set up an escalated financial model of what THAT would look like in 2015?

I mean…is what is coming out of Penn State now in some way far superior (or even equal?) to what they produced back in the seventies? Based on my own hiring experience, the answer is “no”. It isn’t even as good.

So…we are paying more to get worse. OK…Who is surprised?