Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

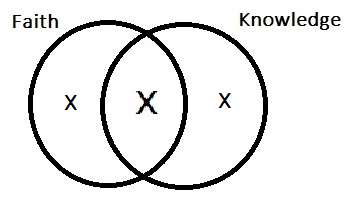

Knowledge and Faith Can Be the Same Thing

Knowledge and Faith Can Be the Same Thing

It is commonly assumed that an item of knowledge and an article article of faith can never be the same thing. This assumption is mistaken. In this post, I will explain only one point: trust in authority can be a source of knowledge. That’s what faith is: trust. It’s still the first definition of “faith” in the dictionary. Also see the Latin fides and the Greek pistis.

It is commonly assumed that an item of knowledge and an article article of faith can never be the same thing. This assumption is mistaken. In this post, I will explain only one point: trust in authority can be a source of knowledge. That’s what faith is: trust. It’s still the first definition of “faith” in the dictionary. Also see the Latin fides and the Greek pistis.

So don’t believe the hype that categorically separates faith from knowledge. This separation ranges from the view William James attributes to a schoolboy (“Faith is when you believe something that you know ain’t true”) to Kant’s more sophisticated idea that “I had to deny knowledge in order to make room for faith” (in beliefs that might well be true).

We should also reject the hype that says that an argument from authority is necessarily fallacious. The best logic textbook in print will tell you otherwise. It will even tell you that there is such a thing as a valid argument appealing to an infallible authority! (“Valid” is a technical term in logic; be sure to look it up first if you’re inclined to complain that there are no infallible authorities.)

Arguments from authority are good or bad depending on what their content is: and primarily on what sort of knowledge the authority is supposed to have, and whether it is reasonable to suppose that the authority really has it.

So an argument from a reliable authority is a good argument, and an argument from an unreliable or untrustworthy authority is a bad argument.

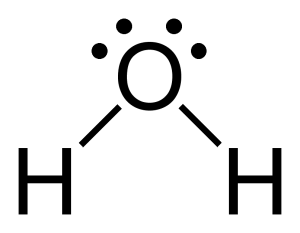

Protons and electrons: an article of faith

We must also dispense with the idea that science is the epistemological opposite of faith: one relying entirely on reason, one not at all. In actuality, religious faith usually relies on reason to varying degrees, up to and including this summary of Christian theology by Thomas Aquinas–quite possibly the most impressive bit of systematic reasoning in human history. And, if Thomas Kuhn is even one-quarter correct, science is not a matter of objective reason alone.

But the bigger point to be made here is that science depends on faith as much as your average religion. That is to say, it depends on trust.

Yes, of course scientific experiments can be replicated. But chances are pretty good that you didn’t replicate them, and that someone else did it for you. And if you yourself did replicate some experiments, did you repeat the replication in order altogether to avoid having to take someone else’s word for it?

To skip over various levels of this exercise, here’s the end-point it leads to, using chemistry as an example. If you want to know something in chemistry without relying on trust, you will have to begin from the very beginning and repeat all of the experiments that led to the current state of chemical knowledge: all of them, multiple times each. You would die of old age before you caught up with the present state of chemical knowledge. And all of your hard work would be useless unless others had the good sense you lacked and were willing to take your word for it at least some of the time when you said that your experiments had turned out the way they had.

Even for scientists, scientific knowledge relies heavily on trust in testimony: the testimony of other scientists. As for the scientific knowledge of those of us who aren’t scientists, we are left where Scott Adams puts us in the Introduction to this book: depending on the word of people (most of whom we’ve never met) who simply tell us how things are.

Augustine (the real Augustine, the Church Father and founder of medieval philosophy) both here (chapter 5) and here (cartoon version here) is even more helpful than Adams. These are the sort of examples he uses:

- Do you know that Caesar became emperor of Rome about 50 BC? Yes; you know it by faith–by pistis, by fides, by trust–in the testimony of historians.

- Do you know that Harare, Zimbabwe, exists? Yes. But if you haven’t been there, then you know it by faith–by pistis, by fides, by trust–in the testimony of geographers or of people who have been there.

- Do you know who your parents are? You know that also by faith–by pistis, by fides, by trust in what they told you.

(On this last point my students instinctively think of DNA tests, at which point I explain to them that they would need not only to perform the test themselves, but to start from the very beginning of genetic science and reinvent it singlehandedly if the goal is to know who their parents are without taking someone’s word for something.)

The Resurrection of the Messiah: an article of faith

No doubt some readers will suspect that I am attacking the legitimacy of science. Not at all. To the contrary, I presume the legitimacy of science.

I am only pointing out that faith, being trust, is something on which science depends; and, since I am in fact assuming that science is a source of knowledge, other beliefs that rely on reliable testimony can also be knowledge.

What you need to get knowledge by trust is a reliable testimony. And we have plenty of reliable testimony: science, history, geography, and (for most of us) our parents. We live our lives by this testimony.

Thus, the crucial question for religious knowledge is this: Do we have any reliable testimony supporting any religious beliefs?

For example:

- Are there any prophets of Jehovah?

- Are there any holy books? Any books that are God-breathed and inspired?

- Is there a real Messiah who can tell us about God and about how we can know God?

- Are there several predictions about the Messiah made centuries before his birth which all converge on the same person?

- Are there accounts of the Resurrection of the Messiah coming from eyewitnesses of sound mind?

- Is there a Roman Catholic Church with infallible authority, or at least a universal church with reliable authority?

Well, yes. We do have some of these things.

And why should you believe me when I say that? That’s a good question. And, more generally, how do you recognize a reliable testimony in religion?

To ask this question at this point is to observe that I have only showed that knowledge and (religious) faith can be the same thing–not that they ever are. It is a possibility, but that doesn’t mean it is a realized possibility.

But that’s enough ground covered for one opening post. Maybe we can talk about whether this possibility is ever realized, and about how we can know whether it is, in comments, or in a new thread.

Note from the author: We did indeed talk about it comments. See comments #s 156-161 for a handy overview of my thoughts on that subject (and an addendum showed up in comments #s 182-183, and another one in comments #s 262-263).

Published in General

I would point you in the direction of Bart Ehrman for a non-credulous reading of the historicity of the Gospels.

A new objection was raised since my overview (comments #s 156-161) of the explanation for my belief in the Resurrection: What if the eyewitnesses recorded in Scripture are not themselves historical?

A book full of replies has no doubt been written; Wright’s book is a good place to start, and I am sure there are others I don’t know about or can’t think of at the moment.

In any case, I thought about it a bit more and decided to give a better overview of this challenge and the proper response to it, in six points.

First: The objection only applies to an eyewitness who is not reporting directly to us.

Second: The historicity of such an eyewitness is established the same way the event an eyewitness testifies to is established: by historical testimony.

Third: The problem emerges when the probability of the event given the eyewitness’ testimony is multiplied by the probability of the eyewitness’ historicity given the testimony of the person who tells us about the eyewitness—and when the result of the multiplication is rather low.

Fourth: This multiplication of probabilities is not a major threat to our knowledge of history—just a minor reduction in the probability for some historical events. (E.g., we know Socrates drank hemlock; Plato hints he wasn’t there, and no one he hints was there ever wrote anything about it that I heard of. So the probability of the event is equal to the probability of the event given the testimony of someone who was there, times the probability that Plato accurately tells us about that person. But we still know that Socrates drank hemlock!)

Fifth: We actually have some eyewitnesses (Matthew, John, Peter, James, and Paul) who are themselves the direct authors of parts of the New Testament—eyewitnesses reporting directly to us. So the problem doesn’t arise there. (And for those who are really suspicious, Paul at least is very well established historically.)

Sixth: The reduction in probability is extremely minor for eyewitness mentioned by Luke. Luke is a very good historian, and he points to numerous eyewitnesses: to Mary and Mary Magdalene and Joanna, to Cleopas and his friend, to the 12 minus Judas minus Thomas (who I think was absent on this particular occasion) plus Matthias, to the guy who was rejected in favor of Matthias, and to Paul.

Now I guess I’ll have to look at your other comments for new things to discuss . . . .

Indeed. But the religions as religions would still be wrong in any case.

No comment. Rather, no new comment. My reply is in #s 156-161.

Now I guess this is a new objection, so I’ll reply. Plato and Aristotle were biased in favor of Socrates, and that has little or no affect on their historical reliability concerning him.

Moreover, if the stories of the Messiah are true then bias in his favor–including missionary work–is the only rational response. So I suspect that an objection to New Testament historicity based on biblical bias relies on presuming against historicity–begging the question again.

I’m surprised no one has brought up Our lady of Fatima yet. If they have, please disregard. And to the bible, more specifically, the new testament. There is no greater affirmation to the validity of the new testament than the old testament.

Wow. Now that is a remarkable assertion! A biased account might be biased in favor of what is true anyway, so we should ignore the bias and forget about objectivity. In fact, being skeptical of a biased account reveals bias in the opposite direction. Again, wow. So, I guess – what? We just flip a coin?

My first reaction was that nobody could believe this, but then I thought about the people who watch MSNBC and read the NY Times…

We shouldn’t forget about objectivity. We just shouldn’t require it. It’s something to carefully consider when considering historical accounts; but that’s all it is. It doesn’t disqualify a historical account; if it did, most of our knowledge of Socrates would not exist; i.e., the beliefs in question would not be items of knowledge.

To be clear, I made no such general remark. The only general remark I would make about biased sources would be that we should be careful with them.

But when we’re dealing with a specific bit of history concerning a person whom the history teaches is truly extraordinary in a very good and frightfully obvious way, things are a bit more complicated. For if the story is true, then reliable and rational sources can be expected to be huge fans of this person; so their being huge fans is no point against them. (Of course, that it is no point against them does not mean that it is a point for them either.)

Here, one more thing and then, as usual, I’m outta here at least till morning.

I think I can boil the second part down to a bit of logic. Consider this argument.

1. If the Resurrection of Jesus is a historical fact, then the historical sources closest to Jesus are huge fans of him.

2. If the historical sources closest to Jesus are huge fans of Jesus, then their reliability is suspect.

So, 3. If the Resurrection of Jesus is a historical fact, then the reliability of the sources closest to him is suspect.

If we’re going to be unbiased on the question of the Resurrection, we must consider the conclusion false.

But it is guaranteed by the premises. So we must consider one of the premises to be false.

The first premise is exceedingly probable, nearly a certainty. So the second premise is most likely false.

Being as you’ve assumed that the Resurrection is true, it really doesn’t matter to you what the people reporting had to say about it. You would apparently know that it’s true deep down in your bones such that even if the Apostles had reported that Jesus turned into a banana the self-evident truth of his resurrection is so overwhelming that it rings out down through the annals of history (and genetic memory) and cries out to you from the pages it is written on.

I’m glad that we have you around to clear up who is and isn’t credible and which events we ought to take for granted in history. I was beginning to worry.

The scriptural account of Jesus’s life makes clear that he was extraordinary, indeed miraculous, long before the resurrection. And yet, somehow, not everyone was an apostle. Or even a fan. To put it mildly. So to dismiss the bias of the apostles as the natural result of witnessing the events of Jesus’s life actually explains very little.

Again, I would not use the word “know” or “knowledge” in this context.

We have strong evidence that there was a historical Socrates, evidence from testimony that Socrates drank Hemlock, little reason to suspect that he didn’t. We might, therefore, say that we’re confident that he drank the Hemlock or — better yet — say that we reasonably assume that he did, but that’s a far cry from genuine knowledge of the kind I take you to mean.

What I’ve been giving is an explanation of why I believe in the Resurrection. About 90% of the explanation is in comments #s 156-161; this is merely an addendum based on an objection that came up after that explanation was summarized.

And, to get to the point, the explanation does not assume the Resurrection.

And the first premise from # 189 is an IF-THEN statement which can be true even if its IF component is not true, and can be known to be true even if its IF component is not known to be true or false.

This remark thoroughly misconstrues the explanation overviewed in #s 156-161.

(And does anyone have genetic memory besides the Goa’old?)

Fair enough. Sin, stupidity, and duck-rabbits might be relevant here. (And politics, which overlaps with sin and stupidity often enough but is not always the same thing.)

But I was talking about the Resurrection, or, if you like, the whole life and death and life–with the miracles and the claims to divinity and Messiahship and the prediction of death and Resurrection and the death and Resurrection themselves. When you put it all together, Premise 1 from # 189 is highly probable.

Do we have a confusion over the word knowledge here? When I say knowledge I just mean knowledge. The dictionary would probably do well enough describing what I mean. Perhaps more precisely than the dictionary: When I say “knowledge” I mean a belief that is true and is also justified or warranted (and does not have the bad fortune to be a Gettier case).

And I know Socrates drank hemlock. I think you do too.

Maybe it’s not the highest quality knowledge, but I’m pretty sure it is knowledge.

(And my explanation of religious belief, by itself, does not explain religious knowledge of particularly high quality. My explanation is a bit simplistic; there’s more explanation available, but I refuse to write a book on it in this thread, and I’m hoping I won’t have to outline a book!)

We have thousands of “eyewitness” accounts of the interventions of Zeus, Ares, Hera, and dozens of other Greek and Roman Gods. We have hundreds of accounts of Yetis spotted in the United States. We have hundreds of first-person accounts of alien abductions, from people still alive. Yet I would assert that we have no “knowledge” of any of these things. In fact, I believe them all to be pure fantasy.

If you are going to accept historical eyewitness accounts of otherwise implausible events as knowledge, Augustine, how do you distinguish between the accounts of the apostles and the accounts of the events listed above?

The questions of Yetis and of Greek gods parallel the alien abduction question addressed in # 160.

I distinguish those accounts in two ways.

1. As far as I am aware (#s 159-160), the testimonial evidence is of a much lower quality. So I don’t believe in Yetis, etc.

2. The broader structure of my religious knowledge (# 161) makes my belief in the Resurrection considerably better warranted than would be my belief in, for example, Yetis, if I did have any such beliefs.

(This is important information. Many Bothans died to bring us this information.)

This thread, which started out so promising, has become deeply disappointing.

You know, that sounds extraordinarily like you’re saying that you believe what you want to believe. I think the word for that is “faith.”

In fact, I would very much enjoy believing in the existence of Yetis. But I have to follow the evidence!

I really don’t understand how I could sound like I’m just believing what I want to believe.

My last comment and its references and the comments immediately preceding those references contain . . .

You can object to one of the premises of my explanation for my belief in the Resurrection.

Or you can say you don’t understand my explanation.

Or you can point out some error in the reasoning.

Or you can say you think there’s an error but can’t quite put your finger on it or don’t have sufficient time and inclination to do so.

And you can even say I’m believing what I want to believe; with the Resurrection, that is true. (Though with Yetis it is different.)

But you can’t say that’s all I’m doing, because I am also reasoning.

Whether I also happen to want to accept the conclusion I accept on the basis of the evidence is irrelevant.

Augustine, I think multiple people have pointed out the problems in your reasoning and the limitations of your evidence and you’ve waived them away.

I was under the impression I had rebutted all objections. Happy to look at a contrary example if you like.

(If you are right, then there’s a good chance either that I’m a bit crazy or that the English language has simply failed as a vehicle of communication.)

Really, this sort of remark makes me wonder if we’re reading the same conversation.

There’s an explanation for my belief in the Resurrection in comments #s 156-161. Some of those comments directly and explicitly rebut the alien abduction objection. There has been no reply to that rebuttal.

The golden plates objection parallels the alien objection, and is (implicitly) rebutted in the same location. It hasn’t come up since.

Objections from Yetis and Greek gods also parallel the alien objections, and I referred them to the appropriate rebuttal. There was no reply.

There was an objection concerning the historicity of the eyewitnesses themselves. I rebutted this objection in comments #s 182-183. Only one reply to my rebuttal showed up, in # 193. My response in # 196 was, as far as I can see, ignored by critics, although someone clicked “Like” on it.

Continued . . .

. . . continued from previous reply:

There was an objection from the bias of biblical authors. I offered two rebuttals and, in return, was compared to MSNBC viewers. Then a rebuttal to my rebuttal showed up in # 192. My reply in # 195 was, as far as I can see, ignored by my critics.

I was the victim (in # 190) of either a straw man fallacy or else a serious failure to read and understand my comments. It happened again (in # 200).

There was one blank remark from you (in # 191).

Long ago, you suggested I was begging a question. I asked you which one; you backed off from the objection.

Mike H. simply disagreed with one of my premises. I respect that. He gave reasons for the disagreement, to which I replied. He then suggested that, since we have contrary intuitions, it would be worthwhile to examine them and see what can be said on their behalf. I agreed, though less optimistically. I thought he would proceed to say something on behalf of his intuition, but he did not. I can’t complain; he may have had plenty of better things to do.

That’s all I can remember at the moment. I wonder what objections you’re talking about. I’ve replied to every objection I noticed and understood.

(CORRECTION: There is one exception somewhere around page 6. I waved it off by accident, thinking I’d replied to it. In actuality I’d replied to a similar one.)

Augustine,

Your argument so far has contained way too many references to books and other independent sources for me to track them all down and read them. I don’t care for that kind of comment. If you have a point to make, you should be able to make it yourself, succinctly, rather than telling me to go read a book. Maybe that means that your argument is stronger than I think. I doubt it, but maybe.

And you can use fancy nomenclature like “inferential warrant.” But so far as I can tell, it all boils down to the fact that the resurrection is consistent with your belief in Christ’s divinity, and therefore you believe the scriptural account of the resurrection.

That is faith, and I think that the vast majority of people recognize that religious beliefs are based on faith. I don’t know what you think you accomplish by trying to reclassify your religious beliefs as “knowledge,” rather than “faith.” But after reading your arguments, I will still confine my definition of historical “knowledge” to things like the Punic Wars or the identities of the Roman Emperors – things that are consistent with the laws of nature and have much, much, much more historical evidence to support them. If a handful of people claim to have witnessed a miracle – whether it be 2,000 years ago or last week – I will continue to be skeptical.

For reasons similar to Larry’s, I don’t feel like going back and retracing the ground either Augustine. At each point where I thought you were making an unsupported, insupportable, or implausible leap with your evidence or your reasoning I made an effort to question it, and at each point it got either ignored or waived away. I think you’re wedded to a set of beliefs for reasons that have nothing to do with the evidence for them. “Faith” is, colloquially, a word often used to describe that phenomenon.

Well, I prefer to call it an explanation because I’m offering it only in order to explain rather than to persuade. But “argument” is a fine enough name for it, because it’s an argument that persuades me. Anyway, . . .

Wait, what? Am I that easy to misunderstand?

There is only one reference in the argument, namely to Wright’s book–well, and various references to the New Testament.

And I did tell you, in #s 156-159, and rather succinctly I thought, what the argument was. The only thing I didn’t do was formalize it. Is that what you want?

Continued below . . .

. . . continued:

Now # 161 is best understood as a response to the sort of objection which I think Tom M. was after in, for example, # 193: That this argument would not by itself provide a great deal of warrant to my belief in the Resurrection. One response is that I can still know some things on similar (and even lower) quality testimony (e.g., that Socrates drank hemlock).

But the response in # 161 was: I got lots more warrant for my belief in the Resurrection; it would take a good book to explain it properly, but I could give you the outlines of it if you want, or if you want the book-length version you can just read Lewis-Stott-Wright.

If I were to give the outlines of it, I would probably do it using those technical terms, which are best understood by reading or skimming the article I linked. There are three technical terms, and what you suggest “it all boils down to” would only be a small component of the outline.

Continued below . . .