Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

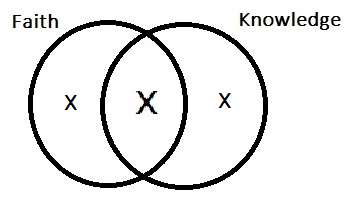

Knowledge and Faith Can Be the Same Thing

Knowledge and Faith Can Be the Same Thing

It is commonly assumed that an item of knowledge and an article article of faith can never be the same thing. This assumption is mistaken. In this post, I will explain only one point: trust in authority can be a source of knowledge. That’s what faith is: trust. It’s still the first definition of “faith” in the dictionary. Also see the Latin fides and the Greek pistis.

It is commonly assumed that an item of knowledge and an article article of faith can never be the same thing. This assumption is mistaken. In this post, I will explain only one point: trust in authority can be a source of knowledge. That’s what faith is: trust. It’s still the first definition of “faith” in the dictionary. Also see the Latin fides and the Greek pistis.

So don’t believe the hype that categorically separates faith from knowledge. This separation ranges from the view William James attributes to a schoolboy (“Faith is when you believe something that you know ain’t true”) to Kant’s more sophisticated idea that “I had to deny knowledge in order to make room for faith” (in beliefs that might well be true).

We should also reject the hype that says that an argument from authority is necessarily fallacious. The best logic textbook in print will tell you otherwise. It will even tell you that there is such a thing as a valid argument appealing to an infallible authority! (“Valid” is a technical term in logic; be sure to look it up first if you’re inclined to complain that there are no infallible authorities.)

Arguments from authority are good or bad depending on what their content is: and primarily on what sort of knowledge the authority is supposed to have, and whether it is reasonable to suppose that the authority really has it.

So an argument from a reliable authority is a good argument, and an argument from an unreliable or untrustworthy authority is a bad argument.

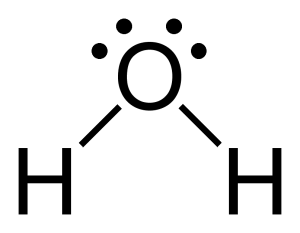

Protons and electrons: an article of faith

We must also dispense with the idea that science is the epistemological opposite of faith: one relying entirely on reason, one not at all. In actuality, religious faith usually relies on reason to varying degrees, up to and including this summary of Christian theology by Thomas Aquinas–quite possibly the most impressive bit of systematic reasoning in human history. And, if Thomas Kuhn is even one-quarter correct, science is not a matter of objective reason alone.

But the bigger point to be made here is that science depends on faith as much as your average religion. That is to say, it depends on trust.

Yes, of course scientific experiments can be replicated. But chances are pretty good that you didn’t replicate them, and that someone else did it for you. And if you yourself did replicate some experiments, did you repeat the replication in order altogether to avoid having to take someone else’s word for it?

To skip over various levels of this exercise, here’s the end-point it leads to, using chemistry as an example. If you want to know something in chemistry without relying on trust, you will have to begin from the very beginning and repeat all of the experiments that led to the current state of chemical knowledge: all of them, multiple times each. You would die of old age before you caught up with the present state of chemical knowledge. And all of your hard work would be useless unless others had the good sense you lacked and were willing to take your word for it at least some of the time when you said that your experiments had turned out the way they had.

Even for scientists, scientific knowledge relies heavily on trust in testimony: the testimony of other scientists. As for the scientific knowledge of those of us who aren’t scientists, we are left where Scott Adams puts us in the Introduction to this book: depending on the word of people (most of whom we’ve never met) who simply tell us how things are.

Augustine (the real Augustine, the Church Father and founder of medieval philosophy) both here (chapter 5) and here (cartoon version here) is even more helpful than Adams. These are the sort of examples he uses:

- Do you know that Caesar became emperor of Rome about 50 BC? Yes; you know it by faith–by pistis, by fides, by trust–in the testimony of historians.

- Do you know that Harare, Zimbabwe, exists? Yes. But if you haven’t been there, then you know it by faith–by pistis, by fides, by trust–in the testimony of geographers or of people who have been there.

- Do you know who your parents are? You know that also by faith–by pistis, by fides, by trust in what they told you.

(On this last point my students instinctively think of DNA tests, at which point I explain to them that they would need not only to perform the test themselves, but to start from the very beginning of genetic science and reinvent it singlehandedly if the goal is to know who their parents are without taking someone’s word for something.)

The Resurrection of the Messiah: an article of faith

No doubt some readers will suspect that I am attacking the legitimacy of science. Not at all. To the contrary, I presume the legitimacy of science.

I am only pointing out that faith, being trust, is something on which science depends; and, since I am in fact assuming that science is a source of knowledge, other beliefs that rely on reliable testimony can also be knowledge.

What you need to get knowledge by trust is a reliable testimony. And we have plenty of reliable testimony: science, history, geography, and (for most of us) our parents. We live our lives by this testimony.

Thus, the crucial question for religious knowledge is this: Do we have any reliable testimony supporting any religious beliefs?

For example:

- Are there any prophets of Jehovah?

- Are there any holy books? Any books that are God-breathed and inspired?

- Is there a real Messiah who can tell us about God and about how we can know God?

- Are there several predictions about the Messiah made centuries before his birth which all converge on the same person?

- Are there accounts of the Resurrection of the Messiah coming from eyewitnesses of sound mind?

- Is there a Roman Catholic Church with infallible authority, or at least a universal church with reliable authority?

Well, yes. We do have some of these things.

And why should you believe me when I say that? That’s a good question. And, more generally, how do you recognize a reliable testimony in religion?

To ask this question at this point is to observe that I have only showed that knowledge and (religious) faith can be the same thing–not that they ever are. It is a possibility, but that doesn’t mean it is a realized possibility.

But that’s enough ground covered for one opening post. Maybe we can talk about whether this possibility is ever realized, and about how we can know whether it is, in comments, or in a new thread.

Note from the author: We did indeed talk about it comments. See comments #s 156-161 for a handy overview of my thoughts on that subject (and an addendum showed up in comments #s 182-183, and another one in comments #s 262-263).

Published in General

http://www.amazon.com/Jesus-Trial-Lawyer-Affirms-Gospel-ebook/dp/B00INC64HK

This is a good read for skeptics. Warning! You might be surprised.

Spoiler alert: The gospels themselves can’t agree with one another on very many of the important aspects of Jesus’ life from his birth down to his last words.

Color me as being skeptical when the (supposedly authoritative) books can’t even agree with themselves about things as important as the circumstances of his birth to what the man said in his final hours.

This digs a little deeper than Wikipedia, Majestyk. To a certain degree, I’ve been a skeptic all my life. Life experience, knowledge, facts and reason have led me to believe. To each his own.

Wikipedia is merely a convenient encapsulation. I’d rather not have to go to Bible Gateway and dig up the relevant passages right now – but I suppose I ought to presume that if I did that tedious work on my own and provided definitive evidence that you’d be convinced?

Believe me, you don’t need to do that. I’ve done plenty of tedious work on my own. I have to say, it was a pretty interesting journey. Especially if you’re a skeptic like I am.

The opening post made a case that knowledge and faith are not epistemological opposites, but in fact overlap, and that religious knowledge is at least possible. The case was borrowed from (the real) Augustine, the Church Father and founder of medieval philosophy.

This is not a thorough defense of the possibility of religious knowledge. I have another case borrowed from Allama Iqbal, and another one from Thomas Reid and Alvin Plantinga.

So the opening post contends for the possibility of religious knowledge—not for its actuality. In the comments we’ve had a (mostly) salutary conversation which (mostly) concerns the actuality of it.

In the next five comments I will more systematically overview what I’ve been saying on behalf of the actuality of religious knowledge. (After these five comments I may still have specific replies to make to specific individuals on matters not covered in this overview.)

Consider this an explanation of why I have faith in Jesus the Messiah—not necessarily an argument that you should do the same.

And please consider this an overview, a rather brief sketch. For a more thorough account of this specific bit of evidence, see N. T. Wright’s book on the subject. And for a more thorough account of why Christianity makes sense, I recommend all three of Stott’s Basic Christianity, Lewis’ Mere Christianity, and Wright’s Simply Christian.

Continued from # 156:

MY VIEW ON MIRACLES

The explanation begins with the possibility of miracles.

My approach to this matter is entirely empirical. I think we can let experience tell us what the laws of physics are. I also think it best not to presume that the laws of physics are absolute. Rather, we should let experience tell us whether those laws are ever broken.

Here a confusion arises, almost as if by instinct—though perhaps it has less to do with instinct and more to do with Hume’s influence. An objection pops into our minds: We posit laws of physics based on what we have experienced. So if our experiences include a certain type of event, we can’t posit laws of physics that exclude it. So it is impossible to have experience of miracles.

The proper reply to the objection is: Like Hume himself said, we can posit—by induction from our experiences—laws of physics which govern the physical world. Whether those laws are on rare occasions overruled by an influence outside the physical world is a question not affecting in any way our ability to posit those laws. The sensible thing to do is to allow experience inform us both what the laws of physics are and whether they are occasionally overruled.

Continued from # 157:

DOES THE EVIDENCE FOR A MIRACLE HAVE TO BE EXTREMELY HIGH?

This question takes us closer to what Hume really said about miracles: That it is more likely that the testimony for an alleged miracle is in error than that the miracle actually took place. In order for me to rationally accept testimonial evidence for a miracle, the reliability of the testimony should exceed the reliability of evidence for the law of physics which is said to be violated.

The proper reply to this is: Thanks for the advice, Hume, but you’re not being a very good empiricist. You assign to a suspension of the laws of physics a probability which is determined by, and only by, the laws of physics themselves. So you are presuming that the laws of physics are absolute. So you are presuming the falsity of the view being discussed—begging the question. A better empiricism would allow experience to inform us both of the laws of physics, and of whether they are broken.

But does the evidence for a miracle still have to be very good? Yes, of course.

The point here is that it doesn’t have to be higher than the evidence for the laws of physics themselves.

Continued from # 158:

THE EVIDENCE FOR THE RESURRECTION OF THE MESSIAH

Now the Resurrection of Jesus, the Messiah, is a historical event. Not counting the Shroud of Turin (of which I have no knowledge in any case), it is established (at least primarily) by the testimonial evidence from the first century eyewitnesses.

And this testimonial evidence is, as testimonial evidences goes, extraordinarily powerful. Here are some of its relevant characteristics:

Notes added in March and August of 2019: The above was not really meant to be a thorough list, but since this is the URL I keep linking back to I’ll be a bit more thorough here. Here are some other salient characteristics of the Gospel testimony:

Continued from # 159:

WOULD THE SAME REASONING COMPEL ME TO ACCEPT THE EVIDENCE FOR ALIEN ABDUCTIONS?

Yes, of course—if the testimonial evidence were equally impressive.

Such evidence could easily reproduce a few of the characteristics of the testimony for the Resurrection. If it had all of them, that would be news to me.

Even if it had all the others, testimony for alien abduction has a rather hard time with the third one: ease of establishing the specific conclusion. (Speaking of which, I myself would not be too quick to rule out the possibility that some of these experiences are genuine, but are not alien abductions. There are alternative explanations, including the demonic.)

Continued from # 160:

CLOSING REMARK ON THE STRUCTURE OF RELIGIOUS KNOWLEDGE

Religious knowledge, like knowledge generally, has a structure–an arrangement, a pattern, an organization.

A belief can be warranted by inferential warrant—evidence from other beliefs. Or it can be warranted by coherential warrant or foundational warrant.

My focus has been on some inferential warrant for the Resurrection, which is both the heart of the Christian faith and my biggest single reason for holding to that faith.

But the warrant for my Christianity has a very complex structure; it is warranted in all three ways, and the inferential warrant goes in more than one direction.

That’s a fancy way of saying that the inference from historical testimony to the Resurrection is the BIG one, but there’s a lot more to the religious knowledge I think I have.

I could say more, but it would be like overviewing a book I haven’t written (at least not yet), and that’s work. So I won’t do it now; but I can probably do it later if anybody wants me to. Anyway, the Lewis-Stott-Wright trilogy already mentioned covers it all pretty darn well.

Luckily, I can write more about those vocabulary words I just used without defining them all. And I did write about it and got it published in an epistemology journal. You can read it here. If I’m right, this is more or less the definitive article on the structure of knowledge.

Something like this might be true: God wants us to trust rather than insist on understanding for ourselves before we accept his message. Or perhaps God wants us to have faith even in the absence of certainty.

But to say that God wants us to have faith instead of knowledge is to misunderstand Christian theology. That would make Augustine and Aquinas and Anselm and Plantinga and Lewis and Wright and Stott into borderline heretics.

Dealing with all the alleged discrepancies would be like writing a book, and that book has already been written–several times.

But a conversation might be possible about one or two. I guess I’m game if you are. Do you wanna raise just one discrepancy as an example?

Sure he can. That’s easy. The existence of the Hittites, the tomb of Caiaphas. Here are a few (some speculative) from 2014: http://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2014/december-web-only/biblical-archaeologys-top-ten-discoveries-of-2014.html

I like the characterization of intuitions in 1-6. (I’m in no mood to quibble, so I’m not going to scour it for little details I don’t like.)

I’m not so sure about 7-8, because I suspect a disagreement of fundamental intuitions that are harder to test through other means; so one of us would indeed be wrong, but it might be hard to determine in any independent way which one of us.

But I’m willing to give it a shot unless some more urgent responsibility gets in the way.

It would also eviscerate the new testament. Jesus was the ultimate proof of his existence.

I’m a bit behind on the conversation, so forgive me if someone addressed this, but this neglects the possibility that the Apostles were either fictional or semi-fictional. One of the things that frustrated me when I first read Mere Christianity is that Lewis, similarly, assumed that the historical Jesus actually claimed His divinity and, therefore, must be either the Messiah or a rotten scoundrel.

“Knowledge” and “known” strike me as inapt in this context. As you say, testimony is a kind of evidence, albeit an indirect and — I would argue — a relatively weak one.* We can say that we have knowledge of the testimony which provides evidence for the thing being testified about, but that’s very different than saying we have any knowledge of the thing itself.

I’m no expert is the field, but there’s been an unsettling and well-evidenced strain of research that shows just how malleable and easily-manipulated our memories are.

Sorry, but I don’t buy it. Of course there are some more-or-less accurate historical and geographical references in scripture. But that’s not what scripture is about. CC’s suggestion was that the religious message of scripture is supported by archaeological evidence. I don’t know of any examples. By analogy, there is sound evidence for the historical American Civil War, but that does not mean that Gone With The Wind is anything other than a work of fiction.

. . . or a nutjob. The famous sum of Lewis is “liar, lunatic, or Lord.”

Fair enough. And I think you got to this point first.

Well, I’m not going into detail because that book has already been written and because I’m not the best one to write it. But I’m quite sure that they are historical and that this is well enough established for at least a lot of them. Paul is known to not be fictional, and Luke is a reliable enough historian, for a start.

I expect Wright’s book will cover this in plenty of detail.

Paul is extremely well sourced and it’s essentially impossible to argue against his existence and authorship of his letters. I should have made this clearer, but my suspicion is that the other Apostles all existed, though I’m dubious as to how accurately they’re described.

Well, to be consistent, you’d have to be suspicious of the possibility of any historical knowledge. There are genuine reasons for caution with testimony and all that, but the fact remains that I have knowledge of various things in history: Socrates was an Athenian philosopher, Caesar became emperor around 50 BC, Lincoln was shot by John Wilkes Booth, Cicero was a Roman orator, etc.

I thought CC said Scripture’s historicity is partially confirmed by archaeology.

And wait a minute here: “that’s not what Scripture is about”? The Bible combines a historical and religious message. All the Abrahamic religions do; if the central historical claims (for Christianity, the sacrificial death and Resurrection of the Messiah) are false, the religion is simply false, and the best that can be said about it is that its moral teachings are on a level with the teachings of Confucius or Plato.

The fact that you concede that there are nakedly discrepant bits is enough for me. We could point to any of them, but I suppose the most important ones are the ones concerning the death of Jesus.

If the Christian narrative is true, there has never and will never be a more important event in the history of mankind. Neil Armstrong’s step onto the Moon is a historical footnote in comparison.

Given how important this event is, you’d think that there would be some consistency in the exact details of what actually happened and more importantly: What Jesus said.

What were Jesus’ last words? According to the Synoptic Gospels, there are several different versions; some of them entirely understandable, and others more fanciful seeming – they strike me as the sort of thing that the author of that narrative would have wanted Jesus to say, as though he were writing a movie script for the Messiah – not the sort of words an actual person going through that trauma would say. This is important and the Gospels can’t agree. They can’t all be correct.

There are of course other troubling problems regarding alleged historical events (darkness, earthquakes, other dead people walking around) which have no corroboration as well, which I’m sure you concede.

Putting aside Socrates, the totality of evidence — testimonial, archeological, etc. — in favor of Caesar’s reign, Lincoln’s assassination, and Cicero’s public career are vastly more convincing than that for Jesus being the Messiah.

I think it’s less helpful to talk about knowledge in this context than confidence. On Caesar, Lincoln, and Cicero, mine approaches 100%, as I imagine yours does. In the case of Socrates and Christ’s existence, mine’s somewhere in excess of 90%. In Socrates’ dialogues being a genuine historical document, my confidence is lower, though still over 50%. In Christ’s divinity, it’s well under 50%.

Your milage may vary.

I concede no such thing. I guess I forgot to include the word “alleged” in that sentence. Sadly, I cannot edit the comment.

No. No, I really don’t.

But if I did it wouldn’t affect the case in the opening post for the possibility of religious knowledge. And the effect on the explanation for my belief in the Resurrection (comments #s 156-161) would be minor, since that explanation does not extend to the infallibility of Scripture.

Ok, so the alleged discrepancy concerns Jesus’ last words. Dude, you have to do better than that. I think there are at least seven things said on the Cross. The four accounts don’t have to each record them all, any more than four newspaper accounts of a contemporary event would have to include all the same quotes from those involved.

Augustine, this is the central problem: we have all of these alleged witnesses – but only maybe 4 of them bothered to have written down what they saw… 50 years later. This get to the malleability of memory that you discussed.

This seems unbelievable. The hard-bitten Roman Soldiers who crucified Jesus didn’t see this stuff going on and report back to their bosses that something fishy is up with this Jesus guy? Why is it only the people who saw Jesus had an interest in getting it believed? Why didn’t Jesus appear before Pilate for the Rub-ins? Why didn’t he appear at the Temple to shame the Sanhedrin?

You can say that there were a lot of witnesses – but these alleged witnesses only exist on the basis of testimony of like maybe 2 people, given the fact that a couple of the Synoptic Gospels seem to have been copied from other authors.

That’s like saying in a police report that you and 500 other people saw something incredible happen. Now, there may have been 500 people, but unless you track those people down to get their reports there actually exists only one report – yours.

So you don’t have an objection to historical knowledge. Jolly good.

Now the explanation for my belief in the Resurrection is overviewed in comments 156-161. I think you (and MajestyK in # 177) have some objection to the historicity of the eyewitnesses themselves, which amounts to a new objection on page 9 of the comments for this thread.

Now I don’t share those concerns; if I did, the historical credibility of Paul and Luke alone would satisfy me as to the historicity of plenty of eyewitnesses. And if I had all the time in the world, I’d read Wright’s enormous book and go into a detailed response on the historicity of the eyewitnesses themselves.

And that’s all. I have things to manage off-line.

Good night, Wesley, sleep well, I’m most likely to kill you in the morning.Good night, Ricochetti, reason well, I’m most likely to converse with you in the morning.If “the best that can be said” about the religious teachings of Judeo-Christian scripture is that they are “on a level with the teachings of Confucius or Plato,” then that’s saying quite a lot. And, of course, billions of people view them as just that. But as history, scripture does not hold up very well. There are too many inconsistencies (and of course the miracles), to accept scripture by the standards that would apply to any other historical work. If some “historian” claimed that Abraham Lincoln had walked on water, I would take that “historian” with a grain of salt. To say the least.

In addition, there is obvious bias at work in the account of scripture. The very word “apostle,” means missionary. The job of a missionary is at odds with the objectivity expected of a historian.