Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

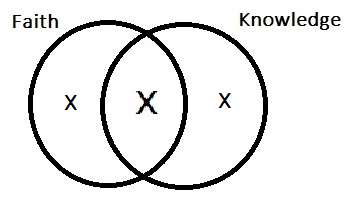

Knowledge and Faith Can Be the Same Thing

Knowledge and Faith Can Be the Same Thing

It is commonly assumed that an item of knowledge and an article article of faith can never be the same thing. This assumption is mistaken. In this post, I will explain only one point: trust in authority can be a source of knowledge. That’s what faith is: trust. It’s still the first definition of “faith” in the dictionary. Also see the Latin fides and the Greek pistis.

It is commonly assumed that an item of knowledge and an article article of faith can never be the same thing. This assumption is mistaken. In this post, I will explain only one point: trust in authority can be a source of knowledge. That’s what faith is: trust. It’s still the first definition of “faith” in the dictionary. Also see the Latin fides and the Greek pistis.

So don’t believe the hype that categorically separates faith from knowledge. This separation ranges from the view William James attributes to a schoolboy (“Faith is when you believe something that you know ain’t true”) to Kant’s more sophisticated idea that “I had to deny knowledge in order to make room for faith” (in beliefs that might well be true).

We should also reject the hype that says that an argument from authority is necessarily fallacious. The best logic textbook in print will tell you otherwise. It will even tell you that there is such a thing as a valid argument appealing to an infallible authority! (“Valid” is a technical term in logic; be sure to look it up first if you’re inclined to complain that there are no infallible authorities.)

Arguments from authority are good or bad depending on what their content is: and primarily on what sort of knowledge the authority is supposed to have, and whether it is reasonable to suppose that the authority really has it.

So an argument from a reliable authority is a good argument, and an argument from an unreliable or untrustworthy authority is a bad argument.

Protons and electrons: an article of faith

We must also dispense with the idea that science is the epistemological opposite of faith: one relying entirely on reason, one not at all. In actuality, religious faith usually relies on reason to varying degrees, up to and including this summary of Christian theology by Thomas Aquinas–quite possibly the most impressive bit of systematic reasoning in human history. And, if Thomas Kuhn is even one-quarter correct, science is not a matter of objective reason alone.

But the bigger point to be made here is that science depends on faith as much as your average religion. That is to say, it depends on trust.

Yes, of course scientific experiments can be replicated. But chances are pretty good that you didn’t replicate them, and that someone else did it for you. And if you yourself did replicate some experiments, did you repeat the replication in order altogether to avoid having to take someone else’s word for it?

To skip over various levels of this exercise, here’s the end-point it leads to, using chemistry as an example. If you want to know something in chemistry without relying on trust, you will have to begin from the very beginning and repeat all of the experiments that led to the current state of chemical knowledge: all of them, multiple times each. You would die of old age before you caught up with the present state of chemical knowledge. And all of your hard work would be useless unless others had the good sense you lacked and were willing to take your word for it at least some of the time when you said that your experiments had turned out the way they had.

Even for scientists, scientific knowledge relies heavily on trust in testimony: the testimony of other scientists. As for the scientific knowledge of those of us who aren’t scientists, we are left where Scott Adams puts us in the Introduction to this book: depending on the word of people (most of whom we’ve never met) who simply tell us how things are.

Augustine (the real Augustine, the Church Father and founder of medieval philosophy) both here (chapter 5) and here (cartoon version here) is even more helpful than Adams. These are the sort of examples he uses:

- Do you know that Caesar became emperor of Rome about 50 BC? Yes; you know it by faith–by pistis, by fides, by trust–in the testimony of historians.

- Do you know that Harare, Zimbabwe, exists? Yes. But if you haven’t been there, then you know it by faith–by pistis, by fides, by trust–in the testimony of geographers or of people who have been there.

- Do you know who your parents are? You know that also by faith–by pistis, by fides, by trust in what they told you.

(On this last point my students instinctively think of DNA tests, at which point I explain to them that they would need not only to perform the test themselves, but to start from the very beginning of genetic science and reinvent it singlehandedly if the goal is to know who their parents are without taking someone’s word for something.)

The Resurrection of the Messiah: an article of faith

No doubt some readers will suspect that I am attacking the legitimacy of science. Not at all. To the contrary, I presume the legitimacy of science.

I am only pointing out that faith, being trust, is something on which science depends; and, since I am in fact assuming that science is a source of knowledge, other beliefs that rely on reliable testimony can also be knowledge.

What you need to get knowledge by trust is a reliable testimony. And we have plenty of reliable testimony: science, history, geography, and (for most of us) our parents. We live our lives by this testimony.

Thus, the crucial question for religious knowledge is this: Do we have any reliable testimony supporting any religious beliefs?

For example:

- Are there any prophets of Jehovah?

- Are there any holy books? Any books that are God-breathed and inspired?

- Is there a real Messiah who can tell us about God and about how we can know God?

- Are there several predictions about the Messiah made centuries before his birth which all converge on the same person?

- Are there accounts of the Resurrection of the Messiah coming from eyewitnesses of sound mind?

- Is there a Roman Catholic Church with infallible authority, or at least a universal church with reliable authority?

Well, yes. We do have some of these things.

And why should you believe me when I say that? That’s a good question. And, more generally, how do you recognize a reliable testimony in religion?

To ask this question at this point is to observe that I have only showed that knowledge and (religious) faith can be the same thing–not that they ever are. It is a possibility, but that doesn’t mean it is a realized possibility.

But that’s enough ground covered for one opening post. Maybe we can talk about whether this possibility is ever realized, and about how we can know whether it is, in comments, or in a new thread.

Note from the author: We did indeed talk about it comments. See comments #s 156-161 for a handy overview of my thoughts on that subject (and an addendum showed up in comments #s 182-183, and another one in comments #s 262-263).

Published in General

Correct, but there’s a difference in kind between the kind of trust one might put in the apostles claims of Christ’s divinity and one one might put in a scientific theorem one has not personally checked for falsification. The latter is available for checking. You can say “I don’t believe that!” and try it yourself.

(Obviously, these two examples hardly cover the full spectrum).

Add to that the fact that scientific knowledge of the sort that I cited is so mundane as to practically be beneath notice.

That is yet another situation in which Augustine is not comparing like with like.

Well, thanks for the conversation! It’s been fun.

Number 1 from the dictionary refers to trust in “things” as well as people, but I was just talking about testimony.

Still quite broad; it covers most things because most knowledge depends, at least in part, on testimony.

But I don’t understand what problem you have with saying that knowledge comes by trust.

Maybe there is no source of knowledge independent of evidence. But there is such a source of truth. Reality itself is to a large degree independent of our cognition. (Even Pragmatists James and Dewey would agree.)

So you insist on using the word “faith” only in ways that preclude any overlap with knowledge. I don’t understand why, since trust is called “faith” and trust in reliable testimony is a source of knowledge.

But I can talk without the word faith. If you define “faith” that way, then the OP’s thesis is that knowledge by trust is possible; there’s no reason a priori to exclude the possibility that some such knowledge could be religious.

Of course I understand that.

Ok, but what’s the problem with the definitions I gave?

I never said they were the only definitions; I’m well aware of several more in the dictionary.

If you like, I can restate the OP’s thesis thus: Some beliefs properly called “faith” are beliefs properly called “knowledge.”

A lamentable way for things to seem! But I wasn’t being deliberately vague.

(One exception: There is some vagueness in the definition of knowledge concerning how much warrant or justification is necessary.)

Sure. Like I said in # 9, I’m not saying that religious knowledge is the same sort of knowledge as scientific knowledge. I’m just saying they both depend on trust. The better comparison for religious knowledge (at least with something like the Resurrection) is not science but history.

(But I don’t want to draw the lines between fact-check-able knowledge by trust and religious knowledge by trust too broadly. There are things like personal religious experience, biblical archaeology, the Shroud of Turin if it’s legit [and I for one have no idea if it is], and intelligent design if the reasoning is good [whether ID is fundamentally a science or a philosophy being a separate question].)

Not at all. As I’ve explained, scientific knowledge and (at least some) religious beliefs are alike in that they rely on trust in testimony.

But things like in this respect are not necessarily the same sort of knowledge, the same quality of knowledge, or confirmed or tested in the same ways (if confirmed at all).

To say otherwise would be to compare like with unlike. But I never said otherwise.

I don’t “insist” on using the word “faith” in ways that preclude overlap with “knowledge.” I just find it useful to use those words to describe different levels of certainty or conviction in my beliefs. You find it useful to define the words in ways that overlap. That’s fine, but I can point out that the overlap exists solely in your definitions – it is not a feature of “reality.”

So far as I can tell, your exercise in semantics seems to be designed to permit you to say that you “know” (i.e., have knowledge) that Christ rose from the dead. My point is that your use of semantics to assert that you “know” this does not increase or decrease the probability of the resurrection, or the strength of the supporting evidence. It’s just word games.

Augustine, Let me make one other point about your analysis here. I have been using the word “evidence” to describe the basis for a belief, and I distinguish between knowledge and faith based on the strength of that evidence. You like to use the phrase “warrant and justification” rather than “evidence.” If there is any difference between these phrases, it appears to me that it is this: My phrase tends to reflect the notion that evidence arises in a vacuum and is evaluated at face value. Your phrase reflects the notion that new evidence is evaluated in light of the observer’s pre-existing beliefs, and gets slotted into the observer’s pre-existing world view in whatever way makes the most sense to the observer.

In this, I think you have a good point. The difference between us, then, is that in my world view I assume that things in the past behaved in the same way that every single thing in the present behaves – i.e., consistent with the laws of physics. Therefore, I have a strong predisposition to be skeptical of claims that miracles have happened. Your world view, in contrast, is more open to the possibility of miracles, so you are more trusting of people who claim to have witnessed miracles.

Well, jolly good.

I don’t understand what we’re disagreeing about anymore. Are we disagreeing that trust in reliable testimony is a source of knowledge? Or that it is at least a possibility that a religious belief could be based on trust in reliable testimony? Or that the testimonial evidence for the Resurrection is pretty impressive? (Any of these would be a disagreement about something more than words.)

Or are we just disagreeing about the way words are used? That’s not a disagreement worth making very much of.

But it’s worth making a little of: This isn’t my definition of “faith.” It comes from the dictionary, it has precursors in Latin and Greek, and it’s used by numerous big philosophers and theologians.

Your definition of “faith” is good too, and I’m sure we can find it in the dictionary. But I get the impression you think I’m doing something inappropriate just by using word in the well-precedented way in which I use it.

Thanks! This seems accurate to me, or close enough. I’ve only mentioned one pre-existing belief relevant to miracles: the empirical criterion from #s 157-158. (But I won’t deny having others!)

Q#1: I don’t disagree.

Q#2: There is certainly such a possibility. If God chooses to appear next Tuesday, in the form of a burning bush 200 feet high, in the middle of Times Square, and reveals his plan for the universe, the cure for cancer, and the location of other planets where He has placed sentient life, I would find that pretty persuasive. (We’ll find out next Tuesday, I guess.)

Q#3: We disagree completely.

Is that because of our different views on miracles?

I imagine it’s that, plus many other things. I suppose the most fundamental difference, though, is that you start off already believing that Jesus was divine. If you did not already believe that, I doubt you would find accounts of the resurrection to be persuasive.

Possibly, possibly. I’m torn between two instincts. One is to say, “YES! That’s just like Plantinga!” Yeah, I started off believing.

The other instinct is to quote Luke Skywalker’s next line after “He told me enough. It was you who killed him.”

The reason for this other instinct is that I would have abandoned my faith long ago if the reasoning didn’t check out as far as I could tell. And if you ask me why I believe the biggest reason (of many, nearly all of which will be just that–reasons) is the Resurrection and the argument for it, which begins with that empirical approach to miracles which you reject.

I don’t think either Larry or I rejects an “empirical approach” to miracles. Speaking for myself, my problem is that I think you’re ignoring contrary evidence and, in my opinion, over weighting what I think is very slight the evidence for your view. My approach, however, is entirely empirical and evidence based and I’d kind of resent an implication to the contrary. I just see evidence you don’t and weight the evidence we both see differently.

As an aside, have you by any chanced noticed a human tendency to be persuaded by evidence which supports a conclusion that was already believed ex ante?

Sure.

The empirical approach to which I refer is explained in #s 157-158. Your approach, if I’m not too confused, is less thoroughly empirical, but I don’t mean to say that it’s not empirical at all.

This:

Thanks for the advice, Hume, but you’re not being a very good empiricist. You assign to a suspension of the laws of physics a probability which is determined by, and only by, the laws of physics themselves. So you are presuming that the laws of physics are absolute. So you are presuming the falsity of the view being discussed—begging the question. A better empiricism would allow experience to inform us both of the laws of physics, and of whether they are broken.

appears to be the money ‘graph of those posts and I think it’s nothing but a shot at a straw man.

I don’t assign the suspension of the laws of physics a low probability because it’s prohibited by the laws of physics. I assign it a low probability because it never — or giving you the benefit of every doubt almost never — happens. That is an empirical observation. It is part of the pertinent evidence.

And it is, by the way, the part of the pertinent evidence you have been refusing to even acknowledge or address for 250 comments now.

I’m confused. Are there some words missing? Or is there some expression about money and graphs that I’m not familiar with?

Anyway, it’s not a straw man; I was talking to Hume. (But there’s always a bit of a chance I got Hume’s argument wrong.)

Oh, good! So you don’t buy either of the Humean arguments. Neat!

Now I’m lost again. When did I refuse to acknowledge that miracles are rare?

Anyway, if we adopt the empirical criterion to which I referred and allow that the probability of a miracle is not determined solely by the laws of physics, I don’t understand why their rarity would count against the extraordinary evidence for any particular miracle.

And, as I said, the Resurrection has some really extraordinary testimonial evidence. Testimonial evidence is good evidence, whether or not it can be independently confirmed. And extraordinary testimonial evidence is really good evidence, even for a miracle–on the presumption of the empirical criterion.

At least, so it seems to me. If there’s some objection to this reasoning that I haven’t already addressed, I have no idea what it is.

Obviously not because I’ve said it a dozen different ways and you keep failing to address it. You seem too smart to be this clueless, so I am beginning to suspect evasiveness. That is your prerogative, but as I said earlier, at some point, I just need to ration the time I spend chasing this particular rabbit.

Well, all I can do is ask to be read charitably: I really am clueless about an objection I haven’t addressed yet. (Too smart to be this clueless? Tell that to my wife!)

Before saying anything else, I reiterate this: I have great respect for the rationing of time as a reason to quit!

I can guess from # 257 that you’re talking about a unique objection–not to the empirical approach I outlined, not to the value of testimonial evidence, not to the really extraordinary nature of the testimony for the Resurrection, but an objection something like this: If miracles are very rare, then the evidence for any particular miracle needs to be not just high but really, really high.

I haven’t noticed that objection before. I’ll address it now in the only ways I know how:

The fast and easy answer: I don’t accept that IF-THEN premise. Is there some reason I should accept it?

The more technical answer: This premise seems to presume that the probability we should assign to any particular miraculous event is primarily a function of something other than the experience of the event itself, or the evidence for those experiences.

In other words, I think my empirical view applies here as well.

I won’t say that the probability we should assign to any particular miraculous event is entirely independent of knowledge of other miracles or of the laws of physics. But its dependence on them is, at best, no greater than its dependence on the basic facts about the event itself, or the evidence for it.

Something old: To consider only the laws of physics in weighing the probability of any particular miracle is to presume that the laws of physics are absolute. This is to presume against miracles; this is to reject miracles a priori rather than to let experience tell us whether they occur.

Something new: To heavily weigh our prior knowledge of miracles in considering the probability of any particular miracle is to presume that we know how often God, if He exists, would do miracles. This is, again, a rejection of experience as a source of knowledge—in this case, knowledge of how often God, if He exists, does miracles.

In my view experience is a source of knowledge of the laws of physics, of whether they have exceptions, and of how often they have exceptions.

Well, I think we have clarity, if not agreement, on two points.

First, Augustine, you have more or less said that you likely would not believe in the Resurrection if you did not believe in the divinity of Jesus, and that you believe in the divinity of Jesus largely because you believe in the Resurrection. You are entitled to circular reasoning if you want it, especially in matters of faith, but you should recognize that circular reasoning is not persuasive evidence of anything. Ever.

Second, you seem to assert that the fact that there has never been a reliably authenticated case of an event happening, isn’t much of a reason to believe that it couldn’t happen. Or so you claim. In fact, nobody (yourself included) actually thinks this way, or they couldn’t navigate everyday life. You can’t go through life thinking that if you step outside you might burst into flames. You have to believe that if you step outside the result will be the same as every time that you or anyone else steps outside – i.e., no flames. Or you simply go mad. Everything we do depends on our belief that the laws of physics will not suddenly be suspended at a moment’s notice. I am confident that when you are not talking philosophy, you conduct yourself consistent with that belief.

On the miracles subject, two thoughts:

For a silly example, I could posit that JFK was assassinated by a sasquatch. But before we investigate that claim too seriously, we should consider “What is likely to be gained from this idea? What questions do I suspect it will answer better than existing answers?”

Sadly, we don’t.

I have no memory of saying anything like this. I can only assume you’re thinking of this remark.

That’s hardly an admission of circular reasoning. It’s really only a bit of biographical information.

And if it is anything more than biography, it’s PLANTINGA. You might not have any familiarity with Alvin Plantinga’s work in epistemology–and I sure wouldn’t blame you for it. It is not—repeat, not—circular.

So what actually is Plantinga’s epistemology? I can explain if necessary. It would need a comment all its own–or a new thread.

Anyway, the following remarks from me should have removed any appearance of circular reasoning:

Continued below . . .

Continued:

And now for more confusion:

I don’t know what’s going on here. I surely live as you describe, and I philosophize the same way–and practice my religion the same way. Nevertheless, I do assert that . . .

And it really isn’t much of a reason. But my recognizing this little fact doesn’t entail that I expect a miracle around every corner. It only entails that I can accept evidence for a miracle when it’s good evidence; I don’t presume against it on some presumption that the laws of physics are absolute or that little old stupid me knows how often God, if He exists, would do such a thing.

One more thing: I’m talking about miracles; you write as I think miracles are the same as randomness. They are nothing of the sort.

Is the “can” in that last clause a reference to what’s metaphysically possible? If so, then we have two choices: Assume that they can be over-ridden, or presume that God’s existence is impossible.

But if the question is “Why should we assume and/or consider that the laws of physics are ever over-ridden?”, I would prefer to answer that we shouldn’t.

Righto. I wouldn’t give that idea a minute’s serious consideration unless there were some evidence it had happened.

It could be a fun X-Files episode if it were done well.

I can think of three ways to handle that question: Accept the other miracles as genuine, reject them as myths, or explain them away as demonic. My best guess that is that all three answers are partially accurate.

Verbiage change accepted.

To which I would ask “And what information do you expect the opposite assumption to yield? Is your expectation plausible?”

But again, we may just be getting stuck on what strikes us as plausible and implausible.

I accept that those are all possible explanations, but it seems extraordinarily difficult to apply those explanations in such a way that validates all Christian miracles but excludes all others. It just becomes incredibly subjective.

Which opposite assumption–the one opposite to the one I don’t make? I just said I prefer not to make an assumption here at all!

My explanation for my belief in the Resurrection starts with an empirical stance: No assumptions beyond an openness to learning from experience–what the laws of physics are, whether they are overridden, and (if God exists at all) how often they are overridden.

You’re not talking about my view, are you? I just said my best guess is that excluding all the others is an error (and some that are excluded as genuine miracles of God are still genuine experiences and supernatural occurrences).

(This may be beside the point, but I reject a lot of alleged miracles from the Christian tradition. I dig MacArthur’s criticism of the Charismatic movement.)