Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

“Ты куда?”: Where has Russia’s Brain Gone? (Borscht Report #6)

“Ты куда?”: Where has Russia’s Brain Gone? (Borscht Report #6)

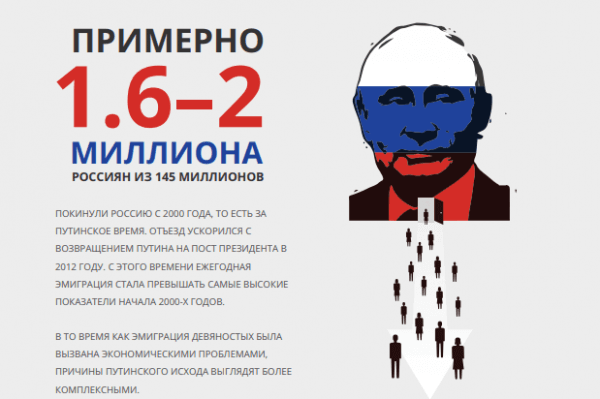

The утечка мозгов/brain drain has been a concern for Russia since the 1990s, when the collapse of the USSR and the resulting political and economic chaos pushed those with sufficient means and desire to escape to do just that. All told, about 2.5 million Russians of various ethnic and economic backgrounds left the country between 1989 and 1999, heading predominantly for the US, Israel, and the EU, especially Germany. Despite the massive gains which the Russian economy saw in the first decade of the 21st century, a further 1.6-2 million people have fled the country since 2000. It would be easy to posit that this is mostly the result of economic issues in the country brought about by Western sanctions and the fall in hydrocarbon prices, or a lack of high paying jobs for skilled people. And these are issues, but a more interesting, and telling, one is at play when we parse the data before and after 2012.

In 2012, Vladimir Putin was re-elected president for a third time. Compared to 2000-2012, the emigration trend sped up. (It’s difficult to say for certain how much it sped up, because of how Russia tracks emigration data; they lump everyone who leaves the country, including workers on a temporary visa returning home and Russian citizens leaving to take up permanent residence abroad, together). If Putin has already been in power so long, why the sudden upturn?

In a 2019 study, the Atlantic Council interviewed 400 Russians living in London, Berlin, San Francisco, and New York. In a 100 point questionnaire, and intensive focus groups, participants were asked about their reasons for emigration, the lives they led before leaving Russia, and their remaining ties to the country. Splitting the post-2012 cohort from its counterparts, and comparing it to data gathered both from this study and with others from consulting firms and the Russian state, the study’s authors found that the post-2012 group was overwhelmingly people that could make a good living in Russia. Only 19% did not have a college degree when they left the country, and 10% remained that way by the time of their participation. Upwards of 35% held a master’s or a Ph.D., and they represented a diverse range of fields, from academic and the performing arts to the sciences and IT.

What unites these people is an almost uniform loathing for Putin and the culture that he has helped to foster in Russia. Participants in that study, and others, cited political repression, a lack of protected human rights, and persecution as among their primary reasons for escape. With Russia’s economic downturn, and the damage that Western sanctions have done to the economy, Putin has encouraged his citizens to accept these realities in the name of patriotism. Everyday Russians must shoulder the burden so that Russia can go on fighting wars in Crimea and the Donbass, intervening in Syria, and working towards reclaiming its great power status.

Meanwhile, a lot of young, creative, educated, and entrepreneurial Russians want to see their country make internal improvements. As one participant said, “every- thing is well-developed…full of interesting jobs, while in Russia everything is in Moscow.” Rather than fighting its neighbors, they think, Russia should be working to eradicate the crony capitalism which has pushed so many of them to start their businesses abroad, securing political freedoms which will protect its citizens and make foreigners more eager to do business, and working on the societal problems (domestic violence, alcoholism, etc) which threaten family structure and social cohesion. Putin taking a third term made that seem an even more distant prospect.

Russians abroad aren’t the only ones who long to escape, at least until Russia boots Putin and makes strides towards pursuing a more modern, liberal democratic model. VTsIOM, the government’s pollster, found that 10% of all Russians want to move abroad permanently. The findings of the Boston Consulting Group, working with HeadHunter, a Russian agency, were no rosier: 57% of people under thirty and 46% of professionals of all age groups desire a permanent move outside of the country. Unlike the old Soviet days, the regime isn’t doing much to stop them. It wants all doubters in the faith of Putin gone, or silenced. Even Putin’s cronies, and the corruption-ridden establishment that has built up around him, prefer to keep their money and their families abroad, often in the West.

The downsides of this for Russia are obvious. Fewer entrepreneurs mean less business growth and less foreign capital investment, more articulate young Russians around the world condemning the government does little to help its image, and society as a whole begins to suffer from a lack of top tier professionals in a variety of fields. These populations present an opportunity for the US and its foreign policy. Of course, we benefit from an influx of creative and hard-working immigrants eager to grow their lives here no matter what. But, unlike earlier immigrants, these ones maintain close ties to Russia. Family and friends seeing them succeed in the US, and the West more generally, is a boon to the popularity and credibility of the American model in Russia, a lived counterpoint to Putin’s propaganda. Likewise, American diplomats and policymakers can work with these immigrants on strategies to appeal to everyday Russians, amplify dissident messages, and plan for a post-Putin Russian Federation.

Russia’s drain can be America’s gain.

Published in Foreign Policy

I think it is also true that their extremely harsh history has resulted in a type of national confusion. What type of psychological toll is dealt out when people must fear for one’s life as Russians did during the time when Stalin’s death patrols might knock on a citizen’s door and take the individual away at 4 in the morning? Add in the deaths and deprivations suffered during WWII, and then the Mafiosa take over of their economy while their society was in transition, 1990 to 1995, and there must be scars we cannot imagine.

My father suffered quite a bit during the Great Depression. That resulted in many moments for him examining the cost of every can of cat food, and every light bulb left on when no one was in the room. (It also meant he was extremely grateful for every sunny day where he had 3 meals, or we all got invited to spend a weekend with his friends at a cottage on the beach.) I still feel guilty should I scrape a half eaten plate of food in the compost pile, thinking it’s good he cannot see it.

But how much worse to have grown up under severe scars from serious overwhelming events.

Russian culture, compared to others, seems to have a harder time bouncing back from national traumas. Germany has soldiered on, and thrived, in the wake of WWII and decades of separation, Taiwan has managed to deal with the in many ways brutal rule of Chiang Kai-shek (as well as accepting and integrating large of amounts of survivors of Chinese atrocities), and Israel, a country made up of a people haunted by hundreds of years of persecution, many actual survivors of the Holocaust, is a flourishing, creative, free state. These aren’t perfect societies, by any means, but others have suffered in a way that’s at least somewhat comparable to Russia and moved ahead.

I certainly feel bad for them, but when we talk about the notion of history in my Russian course, the instructor always says, “none of Russian history is happy.” I wonder if that attitude has contributed to their issues, allowed them to accept too much brutality and lack of freedom because it’s normalized.