Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Building a High Rise on the Foundation of a Colonial Home

Building a High Rise on the Foundation of a Colonial Home

When you’re building something from the ground up, it needs a good foundation. The Empire State building, for example, rests on a foundation that is 55 feet below the surface of the earth. The same applies to business, not just monetarily, but in the way ideas are executed. Rob Long wrote about Netflix’s disruptive influence on television. The question then follows: Is Netflix built on a solid foundation, or will it crumble under its own weight?

When you’re building something from the ground up, it needs a good foundation. The Empire State building, for example, rests on a foundation that is 55 feet below the surface of the earth. The same applies to business, not just monetarily, but in the way ideas are executed. Rob Long wrote about Netflix’s disruptive influence on television. The question then follows: Is Netflix built on a solid foundation, or will it crumble under its own weight?

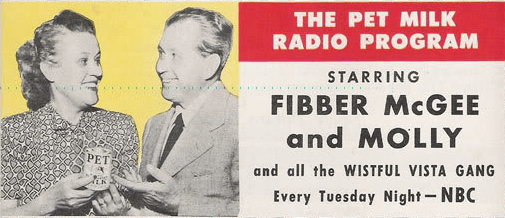

Entertainment media in The United States lays on a foundation dug and set between 1926 and 1927 by two men, David Sarnoff of the Radio Corporation of America and William S. Paley. When those two men established their radio networks — NBC and CBS, respectively — they decided that audiences would receive their product for free and that programming would be paid for by advertisers. The audience, of course, had to purchase their radio sets (a bonus for Sarnoff if you bought an RCA model), but that was it.

1950: After 15 years with Johnson’s Wax, Pet Milk steps in to keep a radio institution on the air. Radio sponsors bailed to television rather quickly.

This model would endure for the next half century. To be sure, there were modest modifications along the way. In the beginning, the networks merely sold time and didn’t do much programming; as such, radio became the medium of advertising agencies. They bought half- and whole-hours and filled them on behalf of their clients. They paid the stars, the writers, producers and directors. The whole ball of wax was theirs.

Jack Berry (Center) and “21” star contestant Charles Van Doren. Notice the prominence of the sponsor’s name on the podium.

That stood right through the early days of television. Then came the quiz show scandals. And when it was revealed that producer Dan Enright was rigging 21, NBC brass claimed that they were just as much the victim of fraud as the general public since they had no control over the content.

Congress held hearings and passed laws (Yes, Virginia, it was Congress that reacted, not the bureaucrats at the FCC) and the networks responded by taking greater control over programming. Full sponsorships gave way to the birth of spot advertising buys.

And so it was until the 1970s. Cable television is as old as TV itself. (Signal meet mountains; mountains meet miles and miles of coaxial cable.) Then, Charles Dolan introduced a little thing called Home Box Office and Ted Turner thought of something called a “superstation” and 24-hour news networks. Slowly, Americans warmed to the idea of paying for additional programming, both with and without commercials.

That success, however, was bought with a price. Reruns of off-network shows slowly migrated from local independent stations to cable networks. And so did the local sports they carried. A segment of society that used to get such programming for free found they were left behind when they could not pay.

Audiences began to scatter. Government responded by approving consolidation and relaxing ownership regulations for broadcasters. It was a temporary save at best. With the advent of the Internet, the fractionalization increased exponentially. The programming fees for cable soared, as did consumer bills. Cord-cutting began.

Now, we stand on the threshold of an on-demand world. Even the networks are there. CBS charges $5.99/month for next-day, on-demand access to all their new programs, along with live streaming from one’s local broadcaster.

Now, we stand on the threshold of an on-demand world. Even the networks are there. CBS charges $5.99/month for next-day, on-demand access to all their new programs, along with live streaming from one’s local broadcaster.

But what are the audiences’ expectations? If they pay on-demand, are they still willing to accept advertising just as they have since 1927? Who will fund development costs? Who’s going to pay for the bandwidth and more infrastructure to carry it? At least in the heyday of broadcasting, the networks didn’t ask you to pay the bills on their transmitters.

“Disruption” is here. But are the foundations there for strength or are we building on rubble?

Published in Culture, Entertainment

I understand all of that, and rather thought I made it clear that I and other cord cutters have decided that this restaurant’s buffet menu price is rather steep. But it also misses the other points I have been making and is something of a sidebar to EJ’s argument here and in prior posts. (cont)

Replace the word “channels” with the word “programs” and maybe I can make my point better.

Breaking Bad and The Walking Dead do not exist without it. (AMC products both. Owner: Cablevision)

Even Netflix used foreign providers in Australia, New Zealand and India to help finance development of House of Cards. Once Netflix entered those markets that development money goes away.

Cards executive producer Beau Willimon boasted four years ago that “TV will not be TV in five years from now…everyone will be streaming.”

My money says that in another year Beau will be proven wrong. Because that last mile of infrastructure you talk about still won’t be built and Netflix will still be limited in how much they can expand.

(cont)

To rephrase EJ’s argument, and put it in the restaurant terms you use: This buffet restaurant makes a couple of really terrific entrees, but they have a huge cover charge, necessary for all of the pretzel-jello salad and reheated tuna noodle surprise hiding the entrees. Worse yet, it’s served on a rotating carousel, so sometimes you sit and wait a long time for that lobster to turn up, scowling over the day-old sushi that keeps going by. The service, meanwhile, is surly and unhelpful. The entrees, if you could buy them alone, would cost a lot less than the whole buffet. Oh, and this joint happens to be the only dining establishment in town.

Well, people are increasingly avoiding the restaurant because of the poor service and the scarcity of digestible entrees (that, and their kids keep filling up on jello). But if the place closes, then who will make those great entrees? Who will employ all those chefs? EJ is here making an argument that despite the endless jello, we still have a moral obligation to support the buffet, because without the buffet, those chefs would be unemployed or else making lower quality meals at inferior competing establishments.

What of it? Cablevision / AMC built its business model the way it is, and whether it lives or dies is not my concern. If Cablevision goes under and never makes another Breaking Bad, does that imply a moral obligation for people to support Cablevision? If the whole TV industry collapses, should we be forced to prop it up?

No. What I’m saying is that the food you enjoy is so expensive, that without the traditional infrastructure, nobody will even grow it, let alone cook it.

Time will tell, and I disagree. But if it comes to that, there are other sources of nourishment. Vaudeville and stage plays lost out to newer forms too.