Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Two Things to Remember About Health Care Policy

Two Things to Remember About Health Care Policy

When trying to formulate a logical, humane health care system, the key is to start from this fundamental understanding: In our wealthy Western countries, we’re not going to let people die in the streets because they can’t afford readily available health care treatments.

When trying to formulate a logical, humane health care system, the key is to start from this fundamental understanding: In our wealthy Western countries, we’re not going to let people die in the streets because they can’t afford readily available health care treatments.

Since everyone knows we aren’t going to turn people away from emergency rooms, a completely free market won’t work. The free rider problem is insurmountable. People can and will choose not to participate in the market until they become sick, and they will then rely on the good will of society to care for them. So the government will be involved in the health care delivery system in some way. Given the free rider problem, it should do so realistically: It should help people at the bottom while keeping government distortion of the market to a minimum.

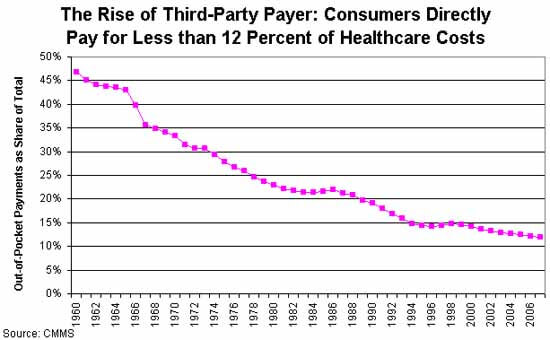

The next thing to consider is the big question: Why is health care so expensive? There’s widespread agreement that third-party payment through insurers is the main problem. There’s no cost control, because neither doctors nor their patients have any incentive to control costs. The only way to gain control over costs is to increase bureaucratic oversight – which adds to the cost.

The next thing to consider is the big question: Why is health care so expensive? There’s widespread agreement that third-party payment through insurers is the main problem. There’s no cost control, because neither doctors nor their patients have any incentive to control costs. The only way to gain control over costs is to increase bureaucratic oversight – which adds to the cost.

Given these two broad parameters, it seems to me that a free-market health care system (or one that’s as free as possible given the first constraint) should begin with universal, single-payer, catastrophic coverage only insurance. That insurance should be very limited in scope to minimize the third-party payer problem.

In a universal catastrophic insurance system, the government would pick up your health care costs, but only if your health care problems reached a threshold such that they were a very significant hardship. This would prevent casual abuse of the system, and it would keep government costs low by eliminating the coverage of routine medical expenses. So: no coverage for routine exams, birth control, small procedures – the things that make up a huge percentage of costs, but should never be paid via an inefficient insurance system. And nothing at all should be covered until you hit your deductible.

To make this palatable to progressives, you can raise the deductible in tandem with income. So a person who makes $20,000 a year might only have to pay for health care until the bills hit $2,000 in a year; a person making $200,000 might be responsible for the first $20,000. Bill Gates might be responsible for the first billion. The numbers and time limits could be negotiated. The important point is that you are responsible for your own health care, but if faced with a health emergency that would bankrupt you, the government will step in. A progressive scheme like this would push more health care into the free market, rather than increasing the scope of government.

Now, would this mean that people would have to pay the deductible out of pocket? Of course not. Employers can offer gap insurance, as can private insurers, on an open market. Gap insurance is much less expensive than full insurance because the insurer’s risk is capped. Pre-existing conditions only cost them up to the cap, so the premium for those would be lower. Because the insurer’s liability is lower for lower-income people (because the cap is lower), insurance would be less expensive for the poor.

People who wish to self-insure could open a HSA and save, say, five times their annual deductible, completely tax-free. This would encourage more people to self-insure to cover the gap, and keep even more of the market out of the third-party payer economy.

This plan would be similar to the health care system in Singapore, a country that spends far less than the US as a proportion of GDP on healthcare, and arguably provides better health care. Singapore also adds a mandatory health savings account, Medisave, to ensure people save enough to pay for the deductible.

Comments?

Published in Domestic Policy, General

The post here would not treat this as a catastrophic illness, would it? And why wouldn’t we prefer there be a significant co-pay for diabetes treatment, as that disease has, in many cases, causal factors that are under the control of the diseased (obsesity, high sugar consumption, lack of exercise, …)?

And is treating this as a catastrophic illness appropriate, activating the Government’s coverage to all afflicted I presume, given that most afflicted can support the costs of their insulin treatments? Or does the catastrophic coverage come means tested? If so, why not just have subsidies for the poor, and leave the rest of society alone, thereby keeping government out of this sector of society? Is not Medicaid something along those lines? (It provides some kind of care for those with a pre-existing condition, does it not?)

If you actually can tell whether the scans would have been equally good, you must have far more information than the average patient would have. That kind of information (what scanner, what sequences, what field strength magnet, what kinds of coils, what level of training the interpreting radiologist has, how well trained the technologist is) is simply generally not available. Unfortunately. And I blame among others my own specialty society for that fact.

Edit: BTW, I am not disagreeing with your point at all. The differences in price are entirely based on market distortions due to the way insurers contract with providers. I am only pointing out that it would be nice if providers could compete on quality rather than on price alone.

That sounds great, but strictly from a financial point of view, for the insurance company, birth control pills are cheaper than pregnancies. Routine exams that pick up cancers early are cheaper than no exams that miss the big expensive things.

The problem with any insurance or reinsurance scheme is that the policy holder – once a claim has started – has the incentive to make the payout as large as possible to make their benefit as large as possible. The problem with your universal catastrophic scheme is that hospitals and providers will do everything in their power to see that once a relatively significant case occurs that the cost of care greatly exceeds the deductible so that their payout is high enough to cover the patients portion that they likely won’t collect.

The majority of health care spending is not the day-t0-day procedures or the catastrophic need of tens of surgeries over 5 years due to a car accident, it is the middle ground stuff like heart bypasses, knee replacements, hip replacements, etc that cost about $30k – $200k a pop. Almost everyone has one of these medical interventions in their lifetime, the problem is that instead of making the recipient pay for it, we have decided that those costs should be socialized (currently through private insurance). Most of these happen in the last quarter of ones life, so one should have the ability to anticipate and save for these. However, we have trained our society that health insurance will pick it up, so they don’t need to save.

Only Type II diabetes is at all a modifiable disease. Type I is not, and has its onset usually in childhood.

That works until you get into issues like developing complications of diabetes, for example renal failure. The problem is that the “diabetes” diagnosis will probably foreclose you getting any kind of insurance, because you are so likely to end up with a complication of some kind or another over time.

The original proposal suggested that there could be a means test for catastrophic coverage.

Because the goal is to unlink employment and health insurance, the linkage having helped lead to the enormous increase in health care costs over time. But if you delink them without some kind of ceiling on what the health insurance companies will have to pay, you will end up leaving lots of deserving people with no option to buy insurance.

I think the risk is that you get into a situation where people can’t afford to become self supporting, because they might lose their Medicaid and not be able to afford care–the welfare trap. That definitely exists; I’ve heard many patients over the years say that they cannot afford to get jobs because they can’t afford to lose their health care.

Absolutely.

Here’s the problem: Decades of third-party payment for health care have led to an increase in cost to the point where virtually no one could pay for the kinds of health care we now take for granted. The proposal in this post is a method for heading back towards the point where market forces might drive down the cost of health care.

As an example, suppose you are a drug company. You have found a marvelous new drug to treat breast cancer. In our current system, your goals are to set a price high enough to cover the years and years of research it took to develop the drug, and then to lobby the government to pay for it so that insurance companies will follow along.

In a non-third-party payer environment, your incentive would be to develop the best possible manufacturing process that would allow you to sell lots and lots of the drug at a price that made it affordable to patients in order to recoup your costs.

The kind of people we will need to help don’t benefit a lot from tax credits, and at the low income end of the spectrum the tax credits are likely not going to cover the cost of any significant health care expenses.

I’m not sure how ‘free market’ a system is when you rely on private insurers but you provide them with a set of customers whose insurance premiums are paid for by government. Then you get the kinds of distortions of the market we see with student loans today.

If the insurance is virtually free then it will not function well to contain costs. The main feature of a catastrophic system is that the government is not involved in funding insurance companies at all. And until you hit your personal deductible the government is not involved in any health care decisions in any way. That’s preferable to a cronyist system where big insurance companies are given huge subsidies from government and then act as agents between the patient, doctor, and government.

No, it means that everyone has skin in the game. Everyone is responsible for the first x% of their own health care costs.

I was trying to find stats on what percentage of the health care budget is consumed by people who spend less than a few thousand dollars per year, vs people who have chronic issues that cost a lot. That data is kind of hard to find. I’m guessing there is a huge age correlation here – young people probably consume health cadre in small bites – emergency room care from accidents, etc.

Elderly people will have more chronic problems. But the elderly are already fully covered under Medicare – which I would also ditch and fold into this system if it could be made politically feasible. There’s no reason a wealthy retiree should have the government pay for all his or her health care if they have the means to pay for some of it.

But this might be a bridge too far for the electorate. I’m a big believer in policy proposals that actually have a chance to pass, and I’m not sure means-testing Medicare will fly.

The type of people we are talking about don’t have savings accounts. And even if they saved a decent percentage of their incomes the savings would be rapidly eaten away by a stint in the hospital. Saving 10% per year of a $20,000 yr income would be very hard to do, and $2000 is nothing when it comes to treating a chronic issue. For example, if you develop Rheumatoid arthritis and need injections of Humira, that can cost you $3,000 per month.

Again, the problem we are trying to solve is that the poor can’t afford the kind of health care they – and we – have decided should be available to everyone. Somewhere, the government has to be involved.

I totally agree with this, but that’s a different discussion – over-regulation of the health care industry.

Good points. Looks like a common sense, centrist view to me…

Single Payer isn’t about bargaining power, it’s about simplicity and efficiency. Sometimes creating a strange hybrid government/private mix is worse than just having one or the other.

Single payer also has many, many flaws. I would never advocate universal single payer coverage of everything. But a very small, very constrained single payer system acting as the provider of last resort to an otherwise unfettered market is quite different.

I think that’s correct. In particular, America is the home of the ‘early adopter’ in new health care innovations. The thing that worries me the most about universal coverage is that the government is not about to spend $20 million on artificial hearts or other exotic treatments. You need rich people and a free market health care system to create the incentives required to research new drugs and devices that by their nature are very expensive when they first come to market. And without them, the middle class and poor never see that stuff trickle down to them.

This is a major flaw with Canada’s system, which otherwise works reasonably well. One of the reasons it works well is because we have wealthy people in the U.S. paying for innovation that eventually makes it to us. Another is that our own wealthy people often opt out of the public health care system and go to the U.S. for treatment of very expensive, very difficult problems.

The starting point of all of this is to change everything to a high deductible plan and do everything possible to alter the pay structure in medicine.

I wish I was in charge of fixing all this. I have the tenacity of Trump and the empathy of a hospital nun. Combine that with a willingness to see all perspectives and the framework is set. Now who’s hiring?

One of the rules of the market is that people will respond to incentives. This has nothing to do with them being ‘bastards’ – it’s more of a social phenomena – a normalization of behavior under a system of shared incentives.

For example, you don’t have to presume that people are ‘bastards’ to assert that if you lowered the price of something to zero, demand for it would skyrocket. Or that if you create a tax deduction, people will take advantage of it if it applies, even if they aren’t part of the group you were hoping to target.

The fact is, when people know that they can walk into an emergency room and get treatment without condition, they will be less likely to pay for insurance to cover that eventuality.

Free markets do not assume that people are good or that they are bad. Free markets work precisely because the incentives in the market force self interest to align with the self-interest of the person you are trading with. It’s the free market that assumes people are ‘bastards’ in this sense, while socialists think a system of skewed incentives can be made to work so long as the ‘right’ people run it, and who blame the subsequent failures of those systems on bad people rather than bad ideas.

I like your plan Dan.

I’d be delighted to pitch in when they make you czar of all health care. Imaging is a huge and ever enlarging piece of the puzzle; can you make me the deputy czarina of imaging?

There are plenty of chronic issues that have very high lifetime treatment costs. Rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, heart disease, hepatitis, the list goes on. Some of these conditions cost thousands of dollars per month to treat, month in and month out.

Certainly end of life treatment is very expensive, but that would be a problem for Medicare, which is already fully government financed.

I don’t follow your argument here. Are you saying that caring for the chronically ill who can’t afford it is nothing more than a gambit to shut people up? And how does that mean people don’t understand medicine or the market?

For one thing, the ‘old system’ existed at a time when we didn’t have treatments for many chronic diseases. Modern health care does far more, and therefore costs far more.

The ‘old system’ also often involved only a single doctor, who could then decide to be charitable for hard cases. The modern health care delivery system generally involves many people working together, which removes a certain amount of pricing autonomy. As an analogy, if you own your own store you can decide to give some of your inventory to the indigent as charity. If you are the manager of a chain store, you don’t have that flexibility.

And that attitude simply won’t fly anymore. Any policy proposal that includes an element of, “Tough luck – sucks to be you” when it comes to health care is a non-starter. Politics is the art of the possible, and it’s important to acknowledge what can be reasonably passed and what can’t.

Of course. Except on the left they use the ‘tragedy’ argument to gain the moral high ground, but their actual proposals are just as much about social engineering and wealth redistribution. For example, choosing to force everyone to pay for birth control, forcing parents to keep kids on their own insurance until age 26, etc. In my opinion, the proper response is to come up with a policy that negates the ‘tragedy’ argument while stopping all the other nonsense.

I think this is a perfect example of how insurance distorts the market. When a provider knows you are insured, the price is going up.

Primarily that it’s only a safety net for emergencies. It does nothing at all to protect people who have chronic illnesses or conditions like cancer.

I agree that private charity is preferable to government charity whenever possible, but I don’t know that private charity can cover these kinds of costs. Also, there are serious issues of cost control and oversight – health care is complex, and the validity of various expenses hard to determine. Charities would be forced to act like insurance companies, with heavy bureaucratic oversight of the process. I’m not sure it would work.

Remember, we are starting with an assumption that health care markets are by their nature distorted. We’re not going to find a perfect solution – we’re looking for the least-bad option.

‘Ripped off’ is a bad term. Health Care providers engage in price discrimination. Price discrimination means setting a price that optimizes profits for each market segment, rather than having one global price.

For example, let’s say you spend a billion dollars to develop a drug. Once you’ve developed it, you might have a decade to sell it at a high profit before the patent runs out and generics come along and drive the price close to the marginal cost of production. Now, your analysis tell you that the optimum price for the drug is $500 per treatment in the U.S – any more and you lose too many customers, any less and you leave money on the table that your customers would have paid.

But you can also sell the drug in Africa. Africans are much poorer, so you discover that the optimal profit is found at $50/treatment, and that’s what you charge for it there.

Does this mean Americans are being ‘ripped off’? Not at all. It means that the pharma company is trying to optimize pricing and make their sales stream more efficient.

One way to look at it: If you passed a law that forced Africans to pay what Americans pay, would it lower the price of the drug in America? Not necessarily. It might just price the drug completely out of the African marketplace, lowering the profits for the pharma company, which could increase prices to Americans.

Now, it’s true that Africans got to take advantage of a billion dollars in research without having to pay for it. But that’s just the nature of the market. In the same way, buyers of of 80’s era Mercedes Benzes paid a lot of money to finance ABS brakes and other safety features that are now being sold at much lower prices to lower-income people. Were they being ‘ripped off’? Or just being charged what the market could bear?

Then the insurance companies would have an incentive to provide them to their customers for free. Do they?

I know we like to blame everything on government, but one of the main reasons health care costs exploded was simply because the march of technology gave us many more tools that we expect to be used to save our health.

That old country doctor with the black bag? He might have looked after you and taken a chicken in payment if you were poor, but his ‘treatment’ of your cancer was likely to be him saying, “I’m sorry – you have cancer” and then maybe prescribing some painkillers. If you actually want that cancer treated with modern radiation therapy, micro-surgery for brain cancer, chemo therapy, advanced diagnostics and the like – well, a chicken isn’t going to cut it. Perhaps a chicken farm…

I think you’re wrong here. The reason all of this outrageously expensive medicine was developed, and is priced prohibitively, is the third-party payer system. And we owe some of that directly to the government (Medicare) and some of it indirectly to the government (wage controls that led to the coupling of health insurance to employment).

If we had not had third-party payers all these years, medicine would have developed very differently. Advances might have been just as huge–perhaps even larger–(look at old, corded telephones and think of the iphone) but the advances would have been in proportion as people could afford them.

I’m talking about the idea that there are many people who would die through insufficient fault of their own and unnecessarily. People just assume that would be true because they can picture it happening.

In reality, if government wasn’t throwing a trillion (trillions of?) dollars and unimaginable regulations at the “problem” there might not be much of a problem that couldn’t be mitigated by private donations. My friend went to the Mayo clinic and made excellent progress on her mystery illness. She was scared to death about the bill even though she has insurance, but it only ended up being like $600 out of pocket when the donations were factored in.

I like this idea because it acknowledges the reality of our journey since WW2: health care has become a non-market distorted by third-party payment, socialized costs, and regulatory capture. Creating and selling a plan that navigates the many delusions the public has about its health care system is no easy feat.

Obama had to lie through his teeth to get Obamacare through. The truth will be harder to swallow.

emergency care is a safety net…but it’s not optimal care for a variety of conditions – both mild and severe.

Also, the government is completely involved in all parts of medical practice. One example, EMTALA – this is the law that prevents emergency rooms from dumping difficult expensive patients on other health systems to avoid the costs.

I don’t understand the poster’s initial premise. If someone shows up for treatment who can’t pay, they may not be allowed to turn them away (I think that’s a federal law from 80s that prohibits that). But the bill still goes to the patient. Medicaid may cover it if they qualify. If not the patient files bankruptcy.

Covering people who can’t pay shouldn’t require rebuilding the entire health care system around the fact that people can’t pay. Any more than the food distribution system is designed around people who can’t afford food.

You can be the czar of all tech issues. You’re hired.

My understanding is that a lot of these debts default, and the hospitals incur the cost and pass it along by baking the costs into other fees.

From here:

I agree, and that’s why I would propose a system like this – one that scales back government involvement in health care and focuses it on the hardship cases, letting the market take care of everyone else.

This plan does not increase government interference in the market – it reduces it. Substantially.

The tax credit is refundable. Everyone benefits.

More of a market than single payer. There is some level of competition. And while some people would want only the bare-bones plan they could afford, most would be prepared to invest a little more for better coverage.

I still don’t see the difference. You’re proposing a single-payer catastrophic coverage only. Walker/Rubio are proposing a tax credit sufficient to cover catastrophic coverage only. Surely everything that you say about it failing to contain costs applies at least equally in single payer — plus, if you want more, you have to work with two plans.

Personally, if I’m going with catastrophic only I’d rather just get the credit and choose my own plan. If I want more than that, I’d rather the choice to spend a little more for more coverage, rather than the paperwork associated with two plans.

Fair enough. The key concept here is that the government only intervenes in cases of catastrophe or gross hardship, and leaves the rest to the market. If tax credits can get there, then maybe that’s a good way to go. I’ll have to look at their plans in more detail.

However… if the tax credit covers 100% of the cost of the catastrophic care, where is the incentive for anyone to control costs?