Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Brave Old World: On Ruining Paris

Brave Old World: On Ruining Paris

The Montparnasse tower is a highrise of such menacing ugliness that it’s become a landmark. Tourists are fascinated by its bleak destructive power.

Let’s start figuring out how to do this kind of journalism. This is an experimental month: I want to figure out how to do a new kind of reporting that involves you, the investor and the reader. I figured the piece I’ve promised to City Journal about Paris’s architectural vandals would be a good place to start. Here are my questions:

- From the Gallo-Roman era to the recent past, almost everything Parisians built was beautiful, in many cases more beautiful than anything else in the world; and at least, not aggressively ugly.

- After the Second World War, Parisians lost this ability — entirely. What has been built since then is at best tolerable, and at worst, among the ugliest architecture in the world.

- Why?

What are your questions?

Something catastrophic certainly happened to architecture throughout Europe after the Second World War. Europe is justly famed for beautiful cities, but none of that beauty was created after the war. The mystery of that is profound. What causes a whole continent suddenly to lose its genius? That there’s a connection to the war is clear, but what exactly was the cause and the mechanism of the loss?

Now, I need to make the case that my judgments about this aren’t arbitrary. I’m saying something more objective about beauty than, “I like building A but I don’t like building B.” So I need to start with a robust theory of aesthetics. Here’s what I need it to do:

- It needs to be able to tell us, in some detail, why Building A is more beautiful than Building B. These principles should be broadly applicable to all buildings.

- It would be useful to show that these principles may broadly be applied to the idea of “beauty,” generally.

- I’d like to explore the idea that it’s at least reasonable to associate “the beautiful” and “the morally good.”

- This point must be based on evidence, the nature of which must be defined. So, for example, I want to look at the criminogenic quality of ugly buildings, and the way people tend to get sick and die sooner when they live in and among them.

I’d like to use these questions to test a few platforms for sharing photos and video with you, as well as some audio and video recordings of interviews, to see what works and what doesn’t, technically and conceptually.

So let’s get started.

Here are some people who might be interesting to interview. This is the National School of Architecture at Paris-Val de Seine (ENSAPVS). It’s supervised by the department of architectural management and heritage of the Ministry of Culture. And it’s housed in a building designed by the architect Frédéric Borel, winner of the National Architecture Grand Prize.

Notice anything about it?

That’s right: It’s ugly.

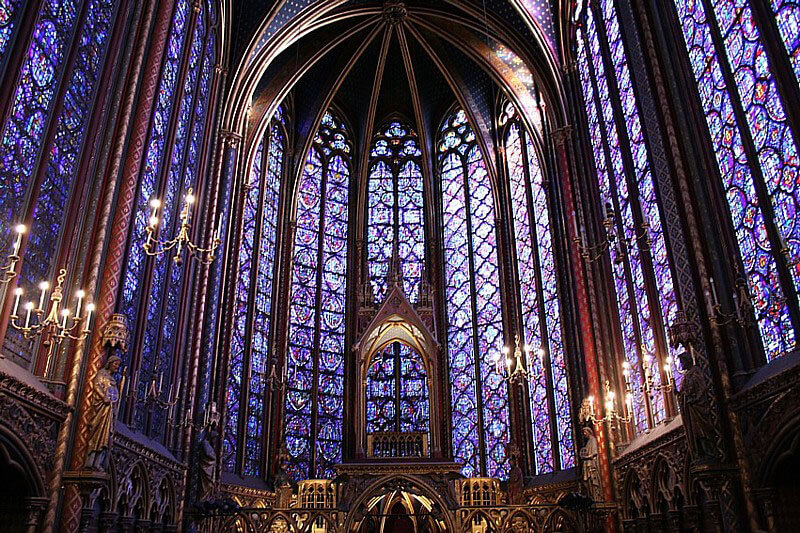

It’s not hideous, but consider what everyone in Paris grows up with, is surrounded by every day, and knows for a fact to be part of his or her heritage. What I’m about to show you are buildings that everyone in Paris walks past every day, and has for his or her entire life:

Recall: the first photo was that of the school of architecture. Not any old building, but one designed to inspire students to the pinnacle of architectural greatness; one designed to showcase contemporary architectural talent. Yet it is — plainly — catastrophically ugly compared to what people here see around them every day. They don’t just read about those buildings in history books, they see them.

Here’s more work by Frédéric Borel. The school of architecture isn’t a one-off mishap. Have a look at his proposal to build, under contract to the city of Paris, “social housing for the autistic.” He won a design competition for the project in 2010. Here’s how he explains his plan. (It’s my translation.)

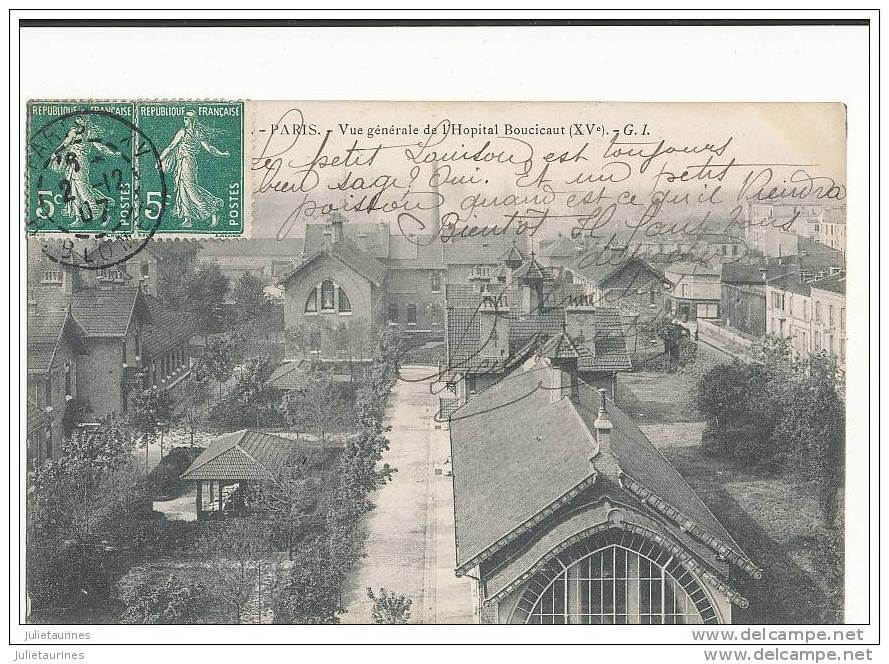

This project is will be inaugurated on one Paris’s sites of philanthropic expression: Madame Boucicaut, the wife of the founder of the Bon Marché department store, wished to build a hospital here. This idea, forgotten in the depths of the 19th century, may seem obsolete today. But this didn’t stop us from dreaming about what today’s philanthropic architecture could be, architecture that would not only protect men and their families, but also aspire to love them. Thus our building is designed so that every dwelling is functional and properly lit. But it also seeks to provide luxurious common areas for its occupants and a landscape of enigmatic forms for passersby. It’s almost as if this building could offer more than just what’s required — some sensuality, some poetry …

We respected the urbanization plan, which suggested we build a T-shape building so that the new layout would blend in with Paris’s urban fabric. But we detached the two wings of the T to avoid a locked-in effect and to open freely to the city. This indentation better recaptures the pavilion composition of the former Boucicaut Hospital, built under the scholarly direction of Paul Chemetov.

The angle of the two streets is marked by a joint drawn by two brick lips that breath, offer respiration, to this crossroads without recoiling. At the same time, the garden captures the light that cuts through this in-between space: not the active and hygienic light of the 19th century, but the playful and lazy light of the 21st century.

Beneath the open corner, there extends a large, carved hall. It emerges like the atrium of a hotel, giving every occupant an address that’s truly welcoming, inviting the desire to meet and be together.

The pedestals and handrails on the ground floor sculpt the ground. They lift and detach from the street, creating higher ground; the single-story shelter for the autistic opens from behind to a sheltered garden.

Before I show you the photo, take note — you probably have already — that this is completely incoherent. It’s not my translation (if anything, I tried to render it more comprehensible than the original); it’s even worse in French. The “hygienic light” of the 19th century? Light in the 19th-century was different from the “playful and lazy” light of the 21st century how, exactly? Why is it a source of pride, in the 21st century, that every dwelling is “functional and properly lit?” — all of Paris has been blessed with electric light for more than a century, so that’s hardly an architectural advance. How do you detach the two wings of a T and still get a T? Beats me. The bit about the brick lips that breathe and respire without recoiling is not only as meaningless in French as it is in English, it’s unconnected to any feature of the building that’s lip-like or visibly designed for any respiratory function.

Do you see “sensuality and poetry” in this?

If so, where?

But even weirder is the appeal to the former Boucicaut Hospital. The architects say, explicitly, that they seek to capture its spirit. Now, that building is no more; it was grievously afflicted by flooding in 1910 and torn down. But sketches suggest it was once at the least inoffensive, and perhaps even beautiful:

Here is the building with which Paul Chemetov proudly replaced it:

Now, you tell me. If you were asked to build a home for those afflicted with complex developmental disabilities that cause substantial impairments in social interaction and communication — one that would also be a workplace for people who care for them — which building would instinctively seem to you the better model? The one built for humans or the one that represents a boot stamping on the human face — forever? (I admit I phrased that question in a leading way, but the photos tell the story well enough.)

What happened here is a mystery. The fact that we take it for granted makes it no less a mystery. Why did France become a wealthier country by far, but lose entirely its genius for making beautiful buildings, over the course of the 20th Century? What do you think?

I’m planning to go to ENSAPVS in the coming days to speak to the faculty and students there. The question I plan to ask is, “What exactly are you folks thinking?”

Are there any questions you’d like me to ask? Are there other people in Paris you think I should interview?

(Oh, and don’t forget: Here’s the GoFundMe page. Feel free to suggest any question about this continent that you’d like me to explore: You’re my employers, my investors, and my customers, so I want to know how to involve you as much as possible — and how to make you happy.)

Published in General

I love it, because it’s really well-built and well-maintained, with great facilities, great staff, and a well-run condo board. I’ve been there for 16 years now, and have no desire to move. Many of the neighbours on my floor have been there since before I moved in.

Gimme function over form, any day.

(Of course, the neighbours hate my building. Screw ’em, sez I. I lives where I likes, yo.)

Gustave Eiffel.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

It seems that WWII had an immense impact of the psyche of everyone involved. I wonder if pre-WWI-WWII the art of constructing ones surroundings was seen as something of an expression of God’s gift of creativity and was soberly done with the mindset that it had to be built to last and built for some sort of greater glory. Post WWII this mindset came to be almost despised in light of all that had been lost (not just physically). The spaces now are not an expression of an individual’s skill for the purpose of being utilized by other individuals, all to God’s glory. It has become a strictly constrained effort by members of an artistic community to adhere to whatever artistic school they believe in at the time to create something that honors that school and can be utilized by the masses.

I think about the local art school here in Pittsburgh. All these little students diddybop around in obvious protest to any established definition of beauty. Yet somehow, they all look the same. Individuality is lost. Creativity is a little to close to Creation. It is much easier and more fashionable to destroy than it is to build. How can one then be a hip destroyer while at the same time having to create something? A built environment must be purposefully built to look evolved from some primordial ooze.

Europe is justly famed for beautiful cities, but none of that beauty was created after the war.

Isn’t the whole Modern Art movement an assault on there being an objective definition of “beauty”. The Modernists are all about promoting let us say heresy, to use Peter Gay’s description, and the biggest heresy of them all is the past as inspiration. The big irony is what we consider the beautiful Paris was the result of, besides Nero’s torching of Rome, the biggest urban renewal project in history. Napoleon III and Baron Haussmann destroyed claustrophobic medieval Paris to make it the city we all love today. Thankfully Haussmann had good tastes. Imagine Ms. Berlinski despair if Le Corbusier got his way for his “renewal” plan for Paris:

Precisely. It’s not the destruction of history to which we object: It’s the destruction of beauty. That’s an important point, because it vitiates the thesis that we’re attracted to old things because they’re old and nostalgia-evoking.

How about the Pugins, Henry Hobson Richardson, George Gilbert Scott

To be fair, folk like Courvoisier and Speer were inflicting their designs upon the world in the 20s and 30s. It’s just that their ideas about planning didn’t get adopted widely until after the war, because there was a lot of “newly-vacant” property that needed to be developed … quickly.

If Courvoisier and Speer had had their way, that land would have been “vacated” by design, rather than by war.

Yes. I often wonder if all this anxiety about the destruction of Western civilization is displaced grief: We destroyed it in two world wars, it’s just been a salvage operation, since.

Admittedly, rather a grand salvage operation. One that involved walking on the moon and elevating more people out of poverty than humankind ever had done before. But still: The West lost its mojo in rather a big way with those wars. And while I used to think the psychic impact on America was very different — insofar as we were the victors — I’m now not sure.

To be fair, a huge amount (perhaps the majority) of that lifting from poverty was accomplished after 1989, if poverty is measured globally.

Just like natural law and the platonic forms, the idea of an objective standard of beauty does exist, but cannot be realized in practice by flawed humans. As such, humanity must allow for subjective standards of beauty in order for new forms to emerge. Any attempt to impose an objective standard of beauty will merely stifle creativity.

I don’t worry about ugly buildings. When architects take chances, some times it’s gonna work and some times it ain’t. The mistakes get demolished and the successes get emulated.

I worry about ugly planning. When governments impose aesthetic rules on architects, designers, developers and engineers the results are almost always disastrous.

The Montparnasse Tower is “ugly” because it’s so out-of-place. The thing is, one reason it’s so out-of-place is that after it was built the construction of buildings over 7 stories high in the city centre was banned. As such, by law, it will always be out-of-place.

Daniel Burnham.

As a recent graduate of architecture school and with 5+ years experience in the architecture profession, I’ve discussed and thought about this topic immensely. If I wasn’t at work and had more time, I would delve into my thoughts more deeply. Here are a couple points I’ve gathered from my perspective:

(continued)

2. As the profession of “architecture” was emerging from the world of “craftsmen”, it slowly disengaged itself from the reality of building (and by that I mean the architects themselves). Fast forward to today and you have architecture students graduating from architecture school having never once picked up a hammer, never once having laid a brick, and never once having sawed a piece of wood. I’m not sure how this specifically relates to ugly buildings, but in my gut I feel it is wrong somehow. I was shocked when I realized this entering architecture school. To me it is like going to school to become a composer without having ever played an instrument. The only reason I myself have hands-on experience as a DIY “craftsmen” in things like woodworking and minor household repair is because my father raised me that way and because I personally chose to pursue those skills on my own time. In my opinion, drawing things others will build without having even minor experience building things yourself is bad practice.

(continued)

3. Points 1 and 2 do not, however, excuse architects and contractors from being able to build simply detailed traditional buildings. Homes (at least here in the US) are still overwhelmingly built with “traditional” styles and details (pretty and ugly), and most residential architects I know design mostly “traditionally” detailed buildings, and do a darn good job. Why do most homebuilders build traditional-style buildings? Because that is what most people want. There are even various movements to build actually honest-to-goodness 100% traditional buildings (not just “looking traditional”). Folks like Clay Chapman.

(continued)

4. Where is the mania, the hunger, and the drive towards contemporary, avant-guarde, asymmetrical, bizarre, striking, bold, brutal, and spartan architecture these days? Academia, academia, academia. I’m not theorizing on this, I’m saying this from personal experience. Ask an American architecture professor who his favorite architect is and they’ll most likely say Corbusier – a man who most people outside of architecture have never heard of, and whose buildings most people have never seen. Young minds go to university and are essentially molded by their studio professors into thinking that historical ornamentation and goo-gas are the the purview of uneducated bumpkins who think that high architecture consists of plastic crown molding purchased at Home Depot. Any architecture student who dares put a peaked roof on their studio project are then met with looks of disgust and intense questioning when they present the final project in front of their black-clad guest critics and peers. I once had a professor tell me my project was too traditional because it had punched windows – it being understood that “traditional” was a bad word. Almost all architecture schools (and definitely all the most “prestigious” ones) in this country align to this opinion. There are very strong ties and similarities between architecture schools and art schools (how many artists graduate from Pratt who paint landscapes?). Building owners (clients) who want to be prestigious follow what the professional architects graduating from these institutions recommend.

(continued)

Was banned before, too. ‘Twas corruption that allowed that monster to be built, after which even the corrupt were so awed in horror of what they’d done that it was thenceforth impossible to bribe them sufficiently to build another.

Me too. It has something to do with “architecture” becoming a profession, rather than a craft, which in consequence released this appalling vanity upon the public sphere.

5. Of course not all architecture schools are like this. Notre Dame‘s architecture school has sort of made a name for itself by focusing on classical architecture. But the reality is that most professors and students at Harvard’s School of Design look down on Notre Dame’s approach to architecture and by extension their graduates.

(continue)

6. Nonsense architect-speak is definitely a product of academia. I’ve never heard so many bizarrely used literary devices as when I was in architecture school. Architecture professors are the worst/best at this, but lead designers in the profession still tend to wind phrases that can leave you befuddled. Most practicing architects I work with and meet have grown out of this (or else it never stuck in school), but those who enter academia tend to retain the jargon habit.

(okay, that ended up being much longer than I expected!)

What an abomination. In what I’ve heard is otherwise a beautiful city, too.

Ah, thank you — really a useful article. I was going to write a section on that subject. Of all disciplines in the arts, few have generated as much amazingly bad writing, in the past half-century, as aesthetics generally, art criticism more particularly, and architecture, specifically. This is neither unrelated to the ugliness nor an accident, I suspect.

Yeah, I agree that there is a lot of vanity in contemporary architecture styles. I recently discovered the Beuron Art School movement out of Germany by some monks in the late 1800’s, and their philosophies of architecture are a striking contrast:

Granted they are talking about religious art and architecture, but the whole emphasis on being anonymous is intriguing. There is a certain amount of humility in borrowing styles and aesthetics from history or a building’s context – blending in vs. standing out.

Thank you for that! Very interesting. I guess I’ve noticed before that I’ve got no complaint with most modern residential work, but I hadn’t thought much about why. It seems architecture is horrible in inverse relation to how much input its future residents and users have in its design. Which is, of course, precisely what a belief in free markets would lead one to expect.

So many different things…

We’re a data people now. Everything’s gotta have a reason. Gotta make sense. Efficient. Useful. Green.

We’re an inside people now. The focus seems to be how the building is perceived from the inside. From the user of the building. The outside can be sacrificed.

We’re specialists now. Architecture is no longer an art. It is a specialization. A school subject. Specialists like to protect their thing. Buildings are designed for the insiders and their secret language.

Ask if they see themselves as artists and who they design for.

Illustrates my point. Good buildings don’t require bribery.

That sentence explains everything I need to know about why a building is ugly.

Two other bullet points I could add as to why contemporary buildings tend to be so similar, boxy, and spartan:

7. Mass-produced modern manufacturing methods of building materials. Most building materials today come out of factories which manufacture products using either linear or planar processes. Extruded aluminum channels instead of cast aluminum shapes. Flat, saw-cut stone veneer instead of individually hand chiseled stone blocks. Bricks aren’t individually pressed by hand anymore but rather extruded like toothpaste from a tube and chopped up at rapid speeds. “Funny” shaped custom bricks are more expensive these days whereas when you make bricks by hand, custom is a minor cost increase. Still not really an excuse why you can’t do simple traditional architecture.

8. Regulations. Building codes have grown immensely since WWII here in the US. Since they were developed in the midst of modern architecture, many of them are written in a way geared towards contemporary architecture. As a small example, here are the Americans with Disabilities Act Standards (which all public buildings in the US MUST comply with – no grandfathering allowed) regarding handrails that aren’t circular:

While I definitely appreciate the ability to firmly grasp a handrail while going up stairs in a public building or business, it does mean that these handrails are illegal to construct in an American opera house because they are too fat (although you could retrofit a second set of railings on top to comply). This is just a minor example.

I have nothing to add. I just quoted this so it would appear twice.

Speaking of ugly modern architecture, have you seen the Canadian Museum of Human Rights? It’s like a giant middle finger to the people of Winnipeg.

http://www.tourismwinnipeg.com/uploads/ck/images/D80_8027%20cropped%2072(5).jpg

As far as post-WW2 architecture in France, I like the Confluence shopping centre in Lyon. The air cushion roof is used to good effect for both the inside and outside aesthetics.

https://structurae.net/structures/confluence-shopping-center

So remember, I’m trying to get all of you involved in shaping the project. You’ve bought shares in a journalist, so to speak, which means you get to decide what questions you’d like me to ask, and of whom you’d like me to ask them.

Any questions for anyone I might be able to find in Paris? Records you’d like to see? My job is to figure out how to find them. I’m your journalist: You tell me what questions you wish you could ask, I’ll ask them.