Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Brave Old World: On Ruining Paris

Brave Old World: On Ruining Paris

The Montparnasse tower is a highrise of such menacing ugliness that it’s become a landmark. Tourists are fascinated by its bleak destructive power.

Let’s start figuring out how to do this kind of journalism. This is an experimental month: I want to figure out how to do a new kind of reporting that involves you, the investor and the reader. I figured the piece I’ve promised to City Journal about Paris’s architectural vandals would be a good place to start. Here are my questions:

- From the Gallo-Roman era to the recent past, almost everything Parisians built was beautiful, in many cases more beautiful than anything else in the world; and at least, not aggressively ugly.

- After the Second World War, Parisians lost this ability — entirely. What has been built since then is at best tolerable, and at worst, among the ugliest architecture in the world.

- Why?

What are your questions?

Something catastrophic certainly happened to architecture throughout Europe after the Second World War. Europe is justly famed for beautiful cities, but none of that beauty was created after the war. The mystery of that is profound. What causes a whole continent suddenly to lose its genius? That there’s a connection to the war is clear, but what exactly was the cause and the mechanism of the loss?

Now, I need to make the case that my judgments about this aren’t arbitrary. I’m saying something more objective about beauty than, “I like building A but I don’t like building B.” So I need to start with a robust theory of aesthetics. Here’s what I need it to do:

- It needs to be able to tell us, in some detail, why Building A is more beautiful than Building B. These principles should be broadly applicable to all buildings.

- It would be useful to show that these principles may broadly be applied to the idea of “beauty,” generally.

- I’d like to explore the idea that it’s at least reasonable to associate “the beautiful” and “the morally good.”

- This point must be based on evidence, the nature of which must be defined. So, for example, I want to look at the criminogenic quality of ugly buildings, and the way people tend to get sick and die sooner when they live in and among them.

I’d like to use these questions to test a few platforms for sharing photos and video with you, as well as some audio and video recordings of interviews, to see what works and what doesn’t, technically and conceptually.

So let’s get started.

Here are some people who might be interesting to interview. This is the National School of Architecture at Paris-Val de Seine (ENSAPVS). It’s supervised by the department of architectural management and heritage of the Ministry of Culture. And it’s housed in a building designed by the architect Frédéric Borel, winner of the National Architecture Grand Prize.

Notice anything about it?

That’s right: It’s ugly.

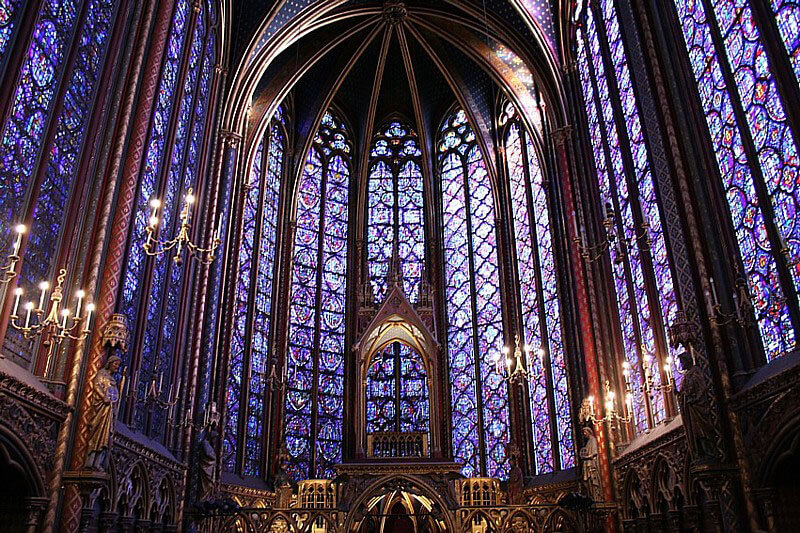

It’s not hideous, but consider what everyone in Paris grows up with, is surrounded by every day, and knows for a fact to be part of his or her heritage. What I’m about to show you are buildings that everyone in Paris walks past every day, and has for his or her entire life:

Recall: the first photo was that of the school of architecture. Not any old building, but one designed to inspire students to the pinnacle of architectural greatness; one designed to showcase contemporary architectural talent. Yet it is — plainly — catastrophically ugly compared to what people here see around them every day. They don’t just read about those buildings in history books, they see them.

Here’s more work by Frédéric Borel. The school of architecture isn’t a one-off mishap. Have a look at his proposal to build, under contract to the city of Paris, “social housing for the autistic.” He won a design competition for the project in 2010. Here’s how he explains his plan. (It’s my translation.)

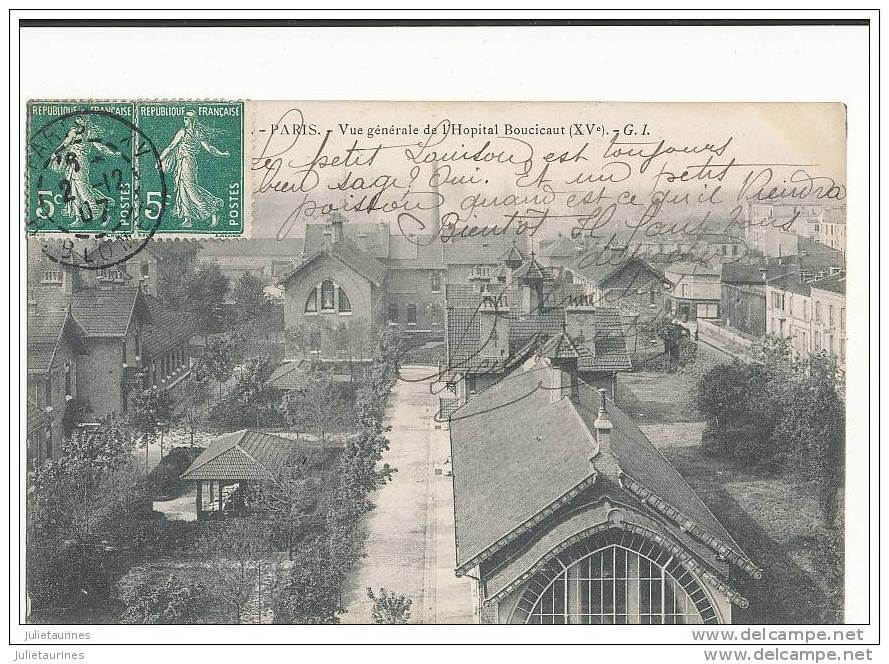

This project is will be inaugurated on one Paris’s sites of philanthropic expression: Madame Boucicaut, the wife of the founder of the Bon Marché department store, wished to build a hospital here. This idea, forgotten in the depths of the 19th century, may seem obsolete today. But this didn’t stop us from dreaming about what today’s philanthropic architecture could be, architecture that would not only protect men and their families, but also aspire to love them. Thus our building is designed so that every dwelling is functional and properly lit. But it also seeks to provide luxurious common areas for its occupants and a landscape of enigmatic forms for passersby. It’s almost as if this building could offer more than just what’s required — some sensuality, some poetry …

We respected the urbanization plan, which suggested we build a T-shape building so that the new layout would blend in with Paris’s urban fabric. But we detached the two wings of the T to avoid a locked-in effect and to open freely to the city. This indentation better recaptures the pavilion composition of the former Boucicaut Hospital, built under the scholarly direction of Paul Chemetov.

The angle of the two streets is marked by a joint drawn by two brick lips that breath, offer respiration, to this crossroads without recoiling. At the same time, the garden captures the light that cuts through this in-between space: not the active and hygienic light of the 19th century, but the playful and lazy light of the 21st century.

Beneath the open corner, there extends a large, carved hall. It emerges like the atrium of a hotel, giving every occupant an address that’s truly welcoming, inviting the desire to meet and be together.

The pedestals and handrails on the ground floor sculpt the ground. They lift and detach from the street, creating higher ground; the single-story shelter for the autistic opens from behind to a sheltered garden.

Before I show you the photo, take note — you probably have already — that this is completely incoherent. It’s not my translation (if anything, I tried to render it more comprehensible than the original); it’s even worse in French. The “hygienic light” of the 19th century? Light in the 19th-century was different from the “playful and lazy” light of the 21st century how, exactly? Why is it a source of pride, in the 21st century, that every dwelling is “functional and properly lit?” — all of Paris has been blessed with electric light for more than a century, so that’s hardly an architectural advance. How do you detach the two wings of a T and still get a T? Beats me. The bit about the brick lips that breathe and respire without recoiling is not only as meaningless in French as it is in English, it’s unconnected to any feature of the building that’s lip-like or visibly designed for any respiratory function.

Do you see “sensuality and poetry” in this?

If so, where?

But even weirder is the appeal to the former Boucicaut Hospital. The architects say, explicitly, that they seek to capture its spirit. Now, that building is no more; it was grievously afflicted by flooding in 1910 and torn down. But sketches suggest it was once at the least inoffensive, and perhaps even beautiful:

Here is the building with which Paul Chemetov proudly replaced it:

Now, you tell me. If you were asked to build a home for those afflicted with complex developmental disabilities that cause substantial impairments in social interaction and communication — one that would also be a workplace for people who care for them — which building would instinctively seem to you the better model? The one built for humans or the one that represents a boot stamping on the human face — forever? (I admit I phrased that question in a leading way, but the photos tell the story well enough.)

What happened here is a mystery. The fact that we take it for granted makes it no less a mystery. Why did France become a wealthier country by far, but lose entirely its genius for making beautiful buildings, over the course of the 20th Century? What do you think?

I’m planning to go to ENSAPVS in the coming days to speak to the faculty and students there. The question I plan to ask is, “What exactly are you folks thinking?”

Are there any questions you’d like me to ask? Are there other people in Paris you think I should interview?

(Oh, and don’t forget: Here’s the GoFundMe page. Feel free to suggest any question about this continent that you’d like me to explore: You’re my employers, my investors, and my customers, so I want to know how to involve you as much as possible — and how to make you happy.)

Published in General

Those who are looking for something uniquely French or European to explain the new architecture need to explain why it is exactly the same as new architecture everywhere, from Miami to Dubai to Shanghai to Sydney. Unlike those cities, Paris actually had a pre-20th Century tradition to draw on, so perhaps the question is why the international style has been adopted even in the face of better exemplars.

I Kant even…

As it happens, I do actually have a couple of questions for a member of the upper class of Paris, or of France generally.

“What do you think the artist was trying to say with the sharp contrast created by using the phallus rampant to separate Institutional Functionality from Cool Sterility and with the specific arrangement of these three elements of design?

“How do you think this artist’s usage contrasts with the architect’s arrangement of the elements of the Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes?”

Eric Hines

I am wondering what the future holds for architects. Is there now or will there be a shift to more traditional architecture?

I know that sustainability and environmentalism generally have been influential in city and town designs in the last fifty years. I’m wondering how that will affect the aesthetics of the buildings architects design. More wood and glass, I would hope.

There is a wonderful PBS documentary about Frederick Law Olmsted that I would recommend to anyone interested in city planning:

http://www.pbs.org/video/2365197253/

I really think it comes down to: Modern architecture, and art, is cheaper to produce.

Ed Driscoll has some other thoughts that he posted at Instapundit in sharing your post that I thought I’d copy here, as after the above root cause, I think he’s got it right:

I completely agree.