Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Brave Old World: On Ruining Paris

Brave Old World: On Ruining Paris

The Montparnasse tower is a highrise of such menacing ugliness that it’s become a landmark. Tourists are fascinated by its bleak destructive power.

Let’s start figuring out how to do this kind of journalism. This is an experimental month: I want to figure out how to do a new kind of reporting that involves you, the investor and the reader. I figured the piece I’ve promised to City Journal about Paris’s architectural vandals would be a good place to start. Here are my questions:

- From the Gallo-Roman era to the recent past, almost everything Parisians built was beautiful, in many cases more beautiful than anything else in the world; and at least, not aggressively ugly.

- After the Second World War, Parisians lost this ability — entirely. What has been built since then is at best tolerable, and at worst, among the ugliest architecture in the world.

- Why?

What are your questions?

Something catastrophic certainly happened to architecture throughout Europe after the Second World War. Europe is justly famed for beautiful cities, but none of that beauty was created after the war. The mystery of that is profound. What causes a whole continent suddenly to lose its genius? That there’s a connection to the war is clear, but what exactly was the cause and the mechanism of the loss?

Now, I need to make the case that my judgments about this aren’t arbitrary. I’m saying something more objective about beauty than, “I like building A but I don’t like building B.” So I need to start with a robust theory of aesthetics. Here’s what I need it to do:

- It needs to be able to tell us, in some detail, why Building A is more beautiful than Building B. These principles should be broadly applicable to all buildings.

- It would be useful to show that these principles may broadly be applied to the idea of “beauty,” generally.

- I’d like to explore the idea that it’s at least reasonable to associate “the beautiful” and “the morally good.”

- This point must be based on evidence, the nature of which must be defined. So, for example, I want to look at the criminogenic quality of ugly buildings, and the way people tend to get sick and die sooner when they live in and among them.

I’d like to use these questions to test a few platforms for sharing photos and video with you, as well as some audio and video recordings of interviews, to see what works and what doesn’t, technically and conceptually.

So let’s get started.

Here are some people who might be interesting to interview. This is the National School of Architecture at Paris-Val de Seine (ENSAPVS). It’s supervised by the department of architectural management and heritage of the Ministry of Culture. And it’s housed in a building designed by the architect Frédéric Borel, winner of the National Architecture Grand Prize.

Notice anything about it?

That’s right: It’s ugly.

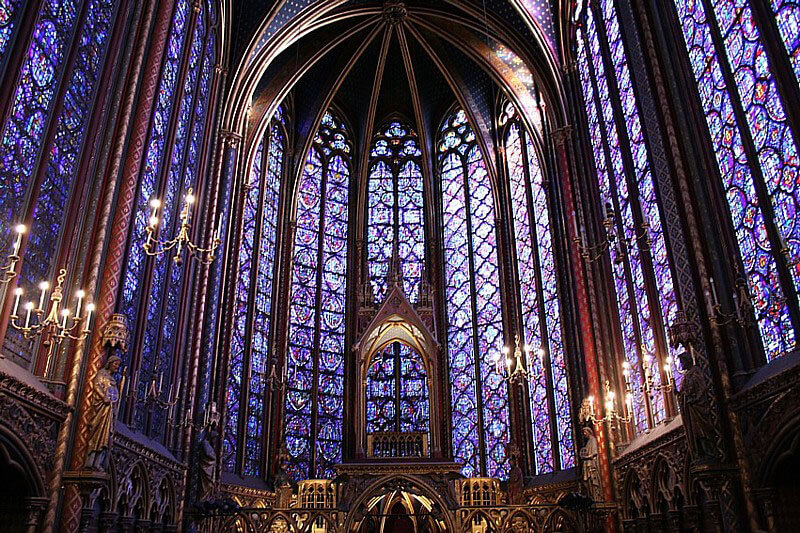

It’s not hideous, but consider what everyone in Paris grows up with, is surrounded by every day, and knows for a fact to be part of his or her heritage. What I’m about to show you are buildings that everyone in Paris walks past every day, and has for his or her entire life:

Recall: the first photo was that of the school of architecture. Not any old building, but one designed to inspire students to the pinnacle of architectural greatness; one designed to showcase contemporary architectural talent. Yet it is — plainly — catastrophically ugly compared to what people here see around them every day. They don’t just read about those buildings in history books, they see them.

Here’s more work by Frédéric Borel. The school of architecture isn’t a one-off mishap. Have a look at his proposal to build, under contract to the city of Paris, “social housing for the autistic.” He won a design competition for the project in 2010. Here’s how he explains his plan. (It’s my translation.)

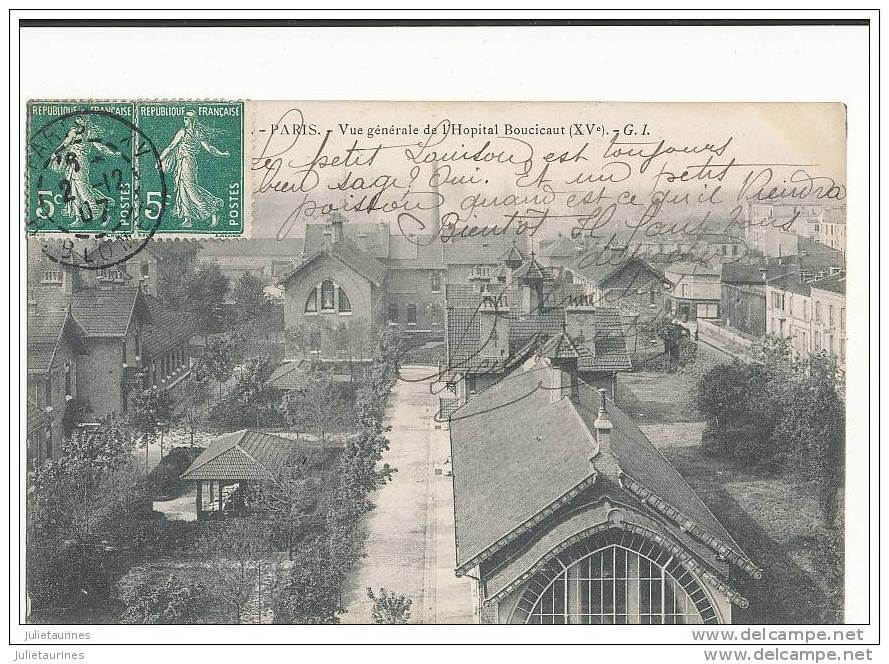

This project is will be inaugurated on one Paris’s sites of philanthropic expression: Madame Boucicaut, the wife of the founder of the Bon Marché department store, wished to build a hospital here. This idea, forgotten in the depths of the 19th century, may seem obsolete today. But this didn’t stop us from dreaming about what today’s philanthropic architecture could be, architecture that would not only protect men and their families, but also aspire to love them. Thus our building is designed so that every dwelling is functional and properly lit. But it also seeks to provide luxurious common areas for its occupants and a landscape of enigmatic forms for passersby. It’s almost as if this building could offer more than just what’s required — some sensuality, some poetry …

We respected the urbanization plan, which suggested we build a T-shape building so that the new layout would blend in with Paris’s urban fabric. But we detached the two wings of the T to avoid a locked-in effect and to open freely to the city. This indentation better recaptures the pavilion composition of the former Boucicaut Hospital, built under the scholarly direction of Paul Chemetov.

The angle of the two streets is marked by a joint drawn by two brick lips that breath, offer respiration, to this crossroads without recoiling. At the same time, the garden captures the light that cuts through this in-between space: not the active and hygienic light of the 19th century, but the playful and lazy light of the 21st century.

Beneath the open corner, there extends a large, carved hall. It emerges like the atrium of a hotel, giving every occupant an address that’s truly welcoming, inviting the desire to meet and be together.

The pedestals and handrails on the ground floor sculpt the ground. They lift and detach from the street, creating higher ground; the single-story shelter for the autistic opens from behind to a sheltered garden.

Before I show you the photo, take note — you probably have already — that this is completely incoherent. It’s not my translation (if anything, I tried to render it more comprehensible than the original); it’s even worse in French. The “hygienic light” of the 19th century? Light in the 19th-century was different from the “playful and lazy” light of the 21st century how, exactly? Why is it a source of pride, in the 21st century, that every dwelling is “functional and properly lit?” — all of Paris has been blessed with electric light for more than a century, so that’s hardly an architectural advance. How do you detach the two wings of a T and still get a T? Beats me. The bit about the brick lips that breathe and respire without recoiling is not only as meaningless in French as it is in English, it’s unconnected to any feature of the building that’s lip-like or visibly designed for any respiratory function.

Do you see “sensuality and poetry” in this?

If so, where?

But even weirder is the appeal to the former Boucicaut Hospital. The architects say, explicitly, that they seek to capture its spirit. Now, that building is no more; it was grievously afflicted by flooding in 1910 and torn down. But sketches suggest it was once at the least inoffensive, and perhaps even beautiful:

Here is the building with which Paul Chemetov proudly replaced it:

Now, you tell me. If you were asked to build a home for those afflicted with complex developmental disabilities that cause substantial impairments in social interaction and communication — one that would also be a workplace for people who care for them — which building would instinctively seem to you the better model? The one built for humans or the one that represents a boot stamping on the human face — forever? (I admit I phrased that question in a leading way, but the photos tell the story well enough.)

What happened here is a mystery. The fact that we take it for granted makes it no less a mystery. Why did France become a wealthier country by far, but lose entirely its genius for making beautiful buildings, over the course of the 20th Century? What do you think?

I’m planning to go to ENSAPVS in the coming days to speak to the faculty and students there. The question I plan to ask is, “What exactly are you folks thinking?”

Are there any questions you’d like me to ask? Are there other people in Paris you think I should interview?

(Oh, and don’t forget: Here’s the GoFundMe page. Feel free to suggest any question about this continent that you’d like me to explore: You’re my employers, my investors, and my customers, so I want to know how to involve you as much as possible — and how to make you happy.)

Published in General

Lastly, I wonder how a design like this is presented – are there multiple preliminary sketches (choices) presented to the customer, in this case, autism groups, the community etc.? Then does the designer go back and incorporate this feedback? Are other architects in the running? I have to sign off now to go earn my keep, and so I can hit the Go Fund Me site later – over and out!

Tourists only go to Le Tour Montparnasse to ascend to the top and look out of it at the glory of classical Paris spread out before them; no one goes to Le Tour in order to see Le Tour.

The Roger Scruton lecture on Vimeo that was linked earlier by crizzyboo is an excellent exposition on modern art and architecture.

I live in a (very) beautiful building that obviously was once designed to provide great comfort to the few and much less to the servants. It’s been completely re-done internally. Stables have been made into apartments; as have servants’ quarters. I live in what was obviously once the servants’ quarters. They’ve put in a completely functional bathroom and a small kitchenette, and done so without destroying the beauty of the building. But my building was lucky: It was part of a historic preservation program implemented by horrified Parisians after they saw what the modern architects would do to Paris if allowed.

I can only barely afford my apartment, and it’s certainly small for one person and seven cats, but it’s a stunningly beautiful building — with fully modern plumbing and electricity.

When I lived here as an actual maid, I shared a primitive toilet with the other servants and had no shower at all (though I had a sink). It was fine — I was only 18. In fact, it was one of the best years of my life. I wouldn’t like that much now, but it wouldn’t be intolerable, either.

We have not yet viewed this entire column, and in fact have only watched the first 15 minutes of the Roger Scruton video, but it is time to jump in with an incomplete observation: The idea of beauty as a truth (that is; intrinsic) began to die as man began to believe that God, the Creator, had died.

Remember the time magazine cover; “God Is Dead”? Not an original thought, but rather a pronouncement; “The death of God, that is, of Creativity, has been accomplished. We no longer have a Creator, hence we no longer have creation, merely invention.”

What passes for art is now merely a new idea, with no intrinsic worth. It is no longer connected to the Creator.

It is still born.

Not a half-bad idea. Did he ever discuss architecture, in particular? He has a lot to say about fine art, but I don’t remember a discussion of architecture.

An artifact like Notre Dame is a combination of the goals of the builders and the capabilities of the materials of the time. The objective of reaching high towards heaven is pretty well known. Try to reach beyond the technology of the day, and you get a collapse, as happened. Much of the visual detail that we admire, like flying buttresses, is a necessity of the construction.

So, I’m wondering, how much of the ugliness of the current generation is due to modern materials (plus an attitude of “If we can, we should”) and what part is due to the driving philosophy of design? I can see some of both in the deliberately outré details of the Boucicaut design, and in the drivel that purports to be its philosophy.

Rather than ask of architects, or of architecture, “Why should people like this?” or “Why should people want this?” I’d try, “Why should people feel they deserve this?”

I would be so much more persuaded of that if I saw that in other fields of endeavor here, the idea of beauty had died. It’s something specific to architecture. In almost every other aspect of everyday life (let’s leave out fine art and music for the sake of argument), Parisians have a tremendous feeling for beauty and an instinct for it. I kept my father company last weekend as he looked for a lampshade — yes, a lampshade. We looked at store after store of the most beautiful, creative, inventive, and artistic lamp shades you’ll ever see. Paris is full of breathtakingly beautiful lampshades. It’s full of beautiful jewelry and furniture, beautiful window-cases full pastries, beautiful womenswear. The impulse to make beautiful things is still entirely part of French culture — but it’s craftsmen, artisans and shopkeepers who keep it alive. It’s in the big things — the buildings — where you see the pathological eagerness to destroy, the vandalism, the indifference to classical and intuitive aesthetic standards. Why?

Who would you ask?

I remember the experiences of apartment-hunting in Milwaukee and the Merrimack Valley cities of MA and NH, being struck by the overwhelming demand for industrial conversions. The market obviously recognized that those 19th-century mills and warehouses had more natural grace than anything the architects would come up with on their own today. What are they teaching in architectural schools that old utilitarian buildings have more beauty by happy accident than modern buildings designed to be seen?

As a point for your investigation, finding someone who has one foot in the world of architectural academy (but only one, so they can still talk some sense) might be very valuable. Can we get an explanation of what modern architects are trying to achieve that isn’t just word salad?

Vanity, for one thing.

Can anyone remember the name of a famous 19th century architect?

I’ll ask — and I’ll bring my digital recorder with me. I’ll share whatever they say.

That’s a happy outcome, but do you think it would be the same if they had thought “Yes, and that Berlinski will need a bathroom and a kitchen and space for her cats” when they built the building in the first place?

And if they weren’t playing catch up – if the building was purpose built for today – would there be more people living in it or fewer?

Those old utilitarian buildings would be really really expensive to build today.

I don’t know if it’s happy accident or that we have learned to perceive bricks in the way that past generations perceived stone.

There is nothing intrinsic about any piece of architecture’s aesthetic – it’s a function of perception, that is a function of (our shared, and constantly evolving) history.

Well … I dunno, because I do think my attic was designed for dwarves or something. That’s why it went unrented for a while before I found it: It’s technically “uninhabitable” space, according to French rental law, but it’s actually completely habitable if you’re a dwarf. Or a cat. Or maybe doves or chickens or some other kind of animal. I just can’t quite figure out how this building used to work. I know one thing: The light switch in the basement is on a timer, and you don’t want to be down there without a flashlight or a phone if that light goes out. Creepy. The sort of thing from which horror movies are made.

I think about the same: The apartments in the building seem about the same size as most in Paris. My apartment has a curious little attic that probably housed the court dwarf at one point. To judge from the faint but unmistakable scent I noticed when I went up there the first time, the most recent inhabitants — well before us — were also cats.

If you’d just witnesses thousand-year-old works of architectural mastery reduced to rubble, I think there might be an impulse to design for function rather than form in the future as well. Why put that level of effort into something that’s just gonna be reduced to dust eventually anyways?

Once it became technically possible for humanity to wipe itself out, the impetus for creating permanent works of art was greatly diminished. Better for the artistically-inclined to focus on more ephemeral forms, like music and/or motion pictures, for example.

Heck, it could be argued that this impulse predates the massive destruction of WWII. After all, the Eiffel Tower was intended to be a temporary structure.

(It’s the same reason I buy things like sunglasses or umbrellas at the dollar store. I know I’m just gonna lose/break them, so why bother spending hundreds of dollars on better quality?)

I don’t believe that’s true. I believe there’s something very much intrinsic to it, and that the standards we use to judge beauty are quite stable from culture to culture, both geographically and temporally.

It’s a tempting hypothesis, but as a historian I wouldn’t say it can be assumed. If I found memoirs or other documents suggesting that this is what they were thinking, I’d be more convinced. Otherwise, it seems just as plausible to me that the impulse would be to build a memorial so beautiful and moving that no one would ever be tempted to go to war again. I mean, no one said, “Let’s not bother putting something where the Twin Towers used to be; after all, the next terrorists will just reduce it to rubble, anyway.” That doesn’t tend to be how humans think. Not consciously, anyway.

I suspect you are aware of this book but George Weigel’s Cube and the Cathedral (which, I heard a talk about but did not read) I believe in part discussed subjects similar to yours.

Although not in Paris, I think one could look at the Frank Geary house (and much of his later work for that matter) as following a similar vein. Abstract expressionism exploring the use of materials as architecture.

All of these seem to be ugly daughters of the Pompidou center, which emphasizes material/structural necessities like ducts and structural members as aesthetic “qualities” of the building. It’s like OK I get it but I want the building to be beautiful as well.

Claire- I highly recommend checking out the fabulous 1999 documentary New York, particularly the section on the master builder and eventual tyrant Robert Moses, who nearly destroyed New York in order to “save it.”

Essentially, architects in 30’s, 40’s and 50’s were enthralled with the ideas of Le Corbusier, who among other things, championed the ideas around minimalism (I’m paraphrasing, I’m no architect).

But when Moses build his high rise housing projects and highways, he was putting Le Corbusier’s ideas into effect, with terrible results. Take for example, a highway and a high rise housing project.

Highway: you immediately put 4 lanes of traffic between the local businesses and 1/3 of their customers. Dry clears, pharmacies, restaurants go out of business. You lose 10% of the available homes for your highway. People are uprooted. Remaining people now live by a 4 lane highway, and home prices fall, starting a downward spiral.

High rise housing project: Clearing the slums to improve living conditions also gets rid of all the stoops in the neighborhood, and the grandmas who sit on them, who keep an eye on kids and troublemakers. Result- crime increases. And instead of having 10-15 neighbors in a brownstone, you now how 500. Community cohesiveness falls. And since high rise housing developments have no retail space, so people must work further away and travel to do basic shopping. And the lack of shopkeepers, pharmacies, etc mean that criminals now can prey on people in a virtual no mans land of open space between buildings. Crime increases again.

All these social ills driven directly by bad architecture and government power. Ugly ain’t the word.

Don’t have my “Critique of Judgement” with me. I’ll check back to you with something definitive later. For the moment, an easy exercise might be to think what idea of morality would be subjectively expressed by a building. We could make this an Architectural Rorschach test. I’ll get us started but please feel free to add.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

Regards,

Jim

Architects have very little say in whether or not “we” go to war. Their designs reflect their own sense of powerlessness in the face of a cruel, uncaring universe and a short, meaningless lifespan.

Western culture hates itself. Why would it build structures that evoke the best of its past when it believes its past is a history of oppression and perversion?

The islamic world still builds nice stuff. They also have a rock-solid belief that they’re awesome.

booyeah!

(They also build a lot of ugly stuff, just saying.)

Perhaps some things are intrinsic (like proportion and space – in relation to the human body?) but the appreciation for different building materials changes, and I think that’s a function of our history.

But then you would miss the answer. Fine art, music and architecture have become the province of a self-selected, self-perpetuating, elite. This is, perhaps, because they (I assume you mean classical a.k.a unsaleable music) are not subject to market forces in the way that fashion and the other applied arts are. (On the other hand, there are many ugly clothes and lampshades designed in Paris, too…)

That’s an interesting point. I’d thought the same thing when I was in Milwaukee — the Blatz brewery, for example, is picturesque because of complicated brickwork that seems ornate mostly because it would be very expensive today. Still, the proportions and aesthetics could be easily and cheaply reproduced in modern materials, so I don’t think it’s just a technological change. Modern utilitarian buildings are more attractive (or less repelling) than some of the celebrated monstrosities Claire has pointed out.

Beauty is hard. Ugly is easy.

I bet you dollars-to-doughnuts that there were plenty of critics who complained these sorts of buildings were hideous monstrosities when they were first built, in much the same way critics hated the Eiffel Tower when it was first built.

Did people really like the Arc de Triomph, or did they just say they liked it to keep Napoleon from lopping off their heads?

Problem is, I would have to see it for about 25 years to know whether or not it looks good. I have learned to have very little faith in my ability to know what I’ll still like after 25 years.