Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

On Desire

On Desire

Let’s talk for a moment about life, the universe and everything. I don’t know any question about life, the universe, and everything to which the answer is definitely Forty-Two (see Douglas Adams), but I can tell you what some of the best questions are: Why aren’t we as happy as we want to be? How can we become happy?

Let’s talk for a moment about life, the universe and everything. I don’t know any question about life, the universe, and everything to which the answer is definitely Forty-Two (see Douglas Adams), but I can tell you what some of the best questions are: Why aren’t we as happy as we want to be? How can we become happy?

So what about the answers? Well, these questions motivated millenia of philosophy, and a good bit of religion, too. A lot of interesting answers have been given, at least as far back as Buddha and as recently as C. S. Lewis. A lot of the big philosophers (Buddhists, Stoics, Epicureans, Platonists, Christians medievals, Descartes, Bacon, Lewis) have agreed on the problem: Our desires don’t fit the world. We desire more than this world has to offer. We desire what we can’t have — or what we can have but can’t keep — and we end up losing what we love, or fearing its loss.

There are two general strategies available to fix that problem: 1) We change what we want, so that we want what we can have; or 2) We change the world, so that we can have what we want.

It’s pretty obvious that both approaches are correct in their own spheres. (And there may be a third option to accompany the first two. See this comment and this comment, below.) The first strategy has been used successfully by everyone who has stopped being a baby who wants his food, wants it NOW, and is miserable because he doesn’t get exactly what he wants.

Medical science is a useful component of the second strategy, and I thank both God and Descartes (who advocated medical science as a component of the second strategy) that we now have the ability to prevent polio.

But what are the proper spheres of these two strategies? Which should be more emphasized? How should we modify the world or modify our desires properly? These are all issues that make big differences between all these thinkers and traditions. Give a thorough answer to all this, and you have a nice little philosophy of desire, or theology of desire, going.

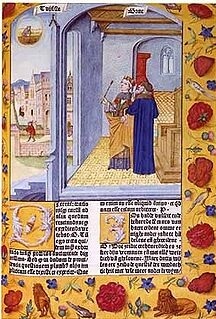

Philosophy tells Boethius how to be happy.

Generalizing somewhat, the earlier philosophers take the first (i.e., change our desires to better match the world), and the early modern Western philosophers take the second approach (i.e., change the world to better match our desires).

There are actually two ways of carrying out the first strategy: either we can cut desire down to the size of whatever is attainable in this world, or we can redirect our desires to something beyond this world. Ancient Buddhists, Stoics, and Epicureans have employed the former of these. The latter is the approach of Sufi mystics, the Bhagavad Gita, the Platonists, the Christian medievals, and C. S. Lewis.

Now it’s time to recommend some books! On the subject of the Platonist, Stoic, and Epicurean philosophers of desire I recommend Martha Nussbaum’s The Therapy of Desire and Pierre Hadot’s What Is Ancient Philosophy?

And on St. Augustine’s philosophy/theology of desire compared and contrasted with Platonism, I recommend — if I may — my own book on Augustine’s Cassiciacum Dialogues. In it, I explain how Augustine mingles the Platonist with the Christian approaches. In one sentence: I explain how Augustine’s theology of desire is a Christian one which takes some insights from the Platonic philosophers. (A bit more detail on where this thesis fits in the context of Augustine scholarship will come up in the next post, and a post after that will summarize the major points of the Cassiciacum dialogues.)

And on the consequences of the modern scientific approach (if you let the worst kind of modern philosophers tell you how to think about right and wrong), I recommend The Abolition of Man by C. S. Lewis.

And to learn how science fiction film illustrates Lewis, I recommend the upcoming Science Fiction and the Abolition of Man: Finding C. S. Lewis in Sci-Fi Film and Television. The book was my idea, and I’m editing it. More on that another time.

Published in General

Oh come now, not every use of passive voice is an attempt to evade responsibility – sometimes we just use it to comply with the word count!

Exactly. He has failed in his vocation.

Sure, abstractions don’t succeed or fail, people do! And he is now a failure – perhaps through no fault of his own (or little fault of his own) – at being a husband.

It’s not like we can’t fail at things for reasons beyond our control. We fail both for reasons beyond our control and for reasons within our control. Obviously, we focus our morals on what we can control because we can’t change the other stuff, but the other stuff happens, too.

Yeah, I’d say rightly-ordered desire is what counts. Completely extinguishing desire through either satisfaction or self-denial probably matters less than prioritizing desires well.

For example, the man who wants to visit the Antarctic penguins may set a low priority on that desire. If, however, he gets cancer and has only a few months to live, or receives an unexpected inheritance, his priorities might change. Maybe he’ll visit the penguins after all. But he may think his life no worse for never having gotten around to it.

Likewise, completely extinguishing the desire to fidget can be overkill. Though fidgeting can be socially obnoxious, it can also aid thought, and fidgeting is good for your health. If one can put the desire to not be socially obnoxious above the desire to fidget when necessary, but not worry so much about it when it isn’t, maybe that’s the right prioritization.

I have a funny story about taking “Thou shalt not fidget” and “Thou shalt not complain” too seriously when I was a kid. It ended with me in the emergency room unnecessarily, causing both parents and teachers tons of needless fuss, because I successfully suppressed the fidgets and complaints that would have attracted help before the problem escalated!

The penguin example helped. I think I understand you pretty well. It’s like my desire to play Halo 3 and following, and have my own pair of roller blades!

The best I can say in reply is (like in comment 44) that some unsatisfied desires may well be consistent with an overall happy life, and even contribute to it. However (like in comment 51), there are distinctions to be made and psychologizings to be done–the upshot of all of which is that the insight that dissatisfaction necessarily subtracts from happiness is hard to overcome.

I could say “I’m happy” plausibly enough despite not having an X-Box 360 (or time to use it). But that unsatisfied desire does subtract from my happiness; as a result I’m not completely happy.

We disagree. I do not believe you can fail in a vocation for reasons beyond your control. A man who has been left by his wife has not failed, and that is not mere semantics. As long as he himself remains faithful he can never fail. This is true freedom of the spirit. A monk who betrays his vow to marry a woman, or because he thinks his talents are underutilized, has failed and will always be a failure until he does justice to that original vow.

Fr. Walter Ciszek was a missionary to Soviet Russia in the late 1930’s. With the start of WW2 he was condemned to the gulag, and spent 20 years in it. During those years he did his best to remain faithful to his vows as a priest, despite the fact that he was almost universally despised, not just by the Communist authorities and guards but by the other prisoners. Many times he was tempted to despair at the lack of results he seemed to be achieving and the apparent waste of his life (and his talents). (continued)

(continued). As time went on, he began to grow in depth of spirit and understand the meaning of vocation, which was to remain faithful to his vows and life as a priest, and leave anything else to God. His ability to eventually get beyond a focus on “results”, and whether he was using his talents appropriately, liberated him. He wrote a book (With God in Russia) about his experiences if you are interested.

One of his points is that the lessons of his life are not just applicable to extreme circumstances like his. I try to follow him in not worrying much about whether I’m being self-fulfilled or using my idiosyncratic talents to the fullest extent, whatever they might be. I try, not always successfully, to stay focused on my vows to my wife, family (I’m married going on 28 years with 3 grown children) and God, and very little about talent exploitation. Am I in the perfect job for me? No, and I never was, but I don’t really care and I’m competent at it. Looking back at my life I realize how little that ever really mattered – it used to bother me – compared to what truly matters. If you get the latter right, it’s not going to matter so much to you what you are doing to make a living.

Well, you can go on believing that. I once believed it, too. But it is contrary to much lived experience. The conflict between moral idealism and lived experience may not bother you much, but it bothers me.

On the other hand, it is not illogical for a man whose wife abandoned him to question whether he simply chose the wrong woman, which would be a failure of judgment. Isn’t the whole point of conservatism taking maximum responsibility for the choices we make, and is not choice of spouse a choice?

Yes, you are competent at it! No wonder it has mattered little to you.

I agree with you that expecting the world, or God, to supply you with the perfect job is asking too much, no matter how much work you yourself put into finding such a job. Merely to be competent at something is a joy, as you yourself have discovered.

Those struggling with merely finding a competence may find it matters more to them.

I should elaborate. Much moralizing presupposes fairly complete knowledge of causality. That virtue X or vice Y caused state Z to happen. But often, real life does not provide us with enough information to be so cocksure of causality.

Take, for example, a brand-new dishwasher that appears to be broken. Were you sent a defective model that’ll never work right, or does it only appear broken because you don’t know how to use it properly yet? From a “God’s-eye view”– which we don’t have – the answer is either one or the other, nothing in between.

But God is all-knowing. We are not. Thus, to us, the question of causality is one of likelihood – which cause is more likely, and why. Accumulating greater knowledge of the dishwasher, through customer assistance or methodically testing it at home, is likely to shift the balance of probabilities in one direction or the other. Likely, but even that’s not guaranteed.

So it’s perfectly possible for two equally-moral adults to disagree on which is the more likely cause, without either sinning. My husband and I are facing that dilemma now.

Now, if the dishwasher doesn’t work because we don’t know how to use it, that is clearly our fault – our insufficient virtue. Simply being more virtuous will solve our problem. If the dishwasher doesn’t work because it really is broken, that is much less our fault (it could be partially our fault for buying the dishwasher from an unreliable supplier when we should have known better, etc). More importantly, being more virtuous will not solve this problem.

No amount of increased virtue will fix a problem whose primary cause is something other than deficient virtue. The best increased virtue can do is take the edge off enduring the problem.

When a person says, “I suffer, I’m unhappy,” the moralizer’s response is practically guaranteed to be, “It’s because you sinned.” Moreover, “Being more virtuous will fix this for you.” Now, in the broadest possible sense, “suffering is only in the world because of sin,” and since we’re all sinners, it’s very hard for any of us to definitively refute the judgment, “If only you were virtuous, you would not be suffering so much.”

For example, if someone suffers foul moods because of migraines, it’s true enough to say that if he were only more virtuous, his moods during migraines would be less foul. He should learn to endure patiently, etc.

On the other hand, fixing the migraine itself might prove a much more efficient way of reducing the vice of foul moods!

Similar logic seems to apply to most of the choices we make in life. Causality is mixed and uncertain, and the answer isn’t always “Just be more virtuous, according to this totally generalized standard of virtue!”

Sometimes the answer isn’t “Don’t fidget!” because “don’t fidget” produces the exact opposite result of what was intended.

Sometimes the answer isn’t “The problem with the younger generation is that they’re too narcissistic and perfectionistic in their career choices! They should stop being so shallow, get married, have kids, and be content with that!” Because, while obsessing over “the perfect career” is unrealistic (and shallow, and wicked, and however many shaming adjectives one cares to use), a career you’re genuinely unsuited for can lead to genuine unhappiness – unhappiness that is, in fact, a signal that you should be doing something else.

These generalized moral judgments, such as J Climacus uses, are fine rules of thumb for hypothetical generic situations where causality is simply assumed to be completely known. But real life happens in particular situations, where causality isn’t fully known. Real-life moral improvement is therefore not quite as “obvious” as the moralizers would like it to be.

What does one do with a long scolding from someone who claims not to like moralizing?

I’m baffled actually. I gave the specific facts of the life of Walter Ciszek as example, and was chastised for talking hypotheticals. Instead, apparently, I should talk about dishwashers. Somehow I think people with migraines should not seek medical help but develop virtue. I can’t imagine where that idea came from.

And, apparently, I hold to the views I do because I think causality is completely known. That’s why, apparently, I think moral improvement is “obvious.” Given my pseudonym, and the thought it represents, the only thing I would think obvious is the unlikelihood I would hold such ideas.

Peace, I’m moving on.

My apologies. It was not intended as a scolding. More as a reasoning-out-loud in response to what I perceived as your scolding ;-)

The example of Walter Ciszek was helpful.

Well, I think that was a neat conversation to read–on the whole, even if it did involve two Ricocheti not quite getting along perfectly, which is sad.

I think I could actually think through this if I put it into terms I can understand: probably using bits of Kant and Aristotle.

I might do it later. But I’m swamped at the moment. Thanks for the conversation, you two!

That is a graceful comment, thank you.

The young man you describe – looking for the perfect career, not satisfied with getting a job and raising kids – was me 35 years ago. The prospect of being just another dad mowing his lawn every week horrified me so much that I failed out of college my sophomore year in despair.

And yet, just a few years later, I found myself living out just that horrible future. But not because I chose it. I fell in love. (Do people do that anymore? I mean the kind of love that is so overpowering it makes you willing to face a prospect you so recently despised simply because you desire to be with someone and nothing else matters?)

Of course that initial rush of excited love faded and I was faced with the future of lawn mowing and the not-so-exciting job. It was then I discovered thinkers like Kierkegaard and the French philosopher Gabriel Marcel, and from them I learned what people used to know as a matter of course, but has been forgotten in the “Me Generation” and beyond (I grew up in the ’70s). (cont.)

And that is that my earlier problem was not that I couldn’t find the right career path to fulfill my talents, or that I didn’t know myself well enough, or whatever I thought it was. It was that I was focused on myself in the first place. Paradoxically, I could only find myself by forgetting myself and instead focussing on others and my responsibilities to them.

Now how those others respond or what eventually results is not something I can ultimately control – I don’t have a complete control of causes, as you say. But I am in charge of my own faithfulness, and God doesn’t ask me to guarantee results, only to remain faithful. It turns out that what I thought would be a boring, soul-crushing existence mowing my lawn every week instead turned out to be an epic adventure of the soul demanding things of me I never imagined. And I feel ashamed that I ever despised those middle aged men and their allegedly boring lives.

And I wish I could knock some sense into the young men I see who have no idea what it means to be a man or what life is about. Not because they should just shut up and be content with a boring job and a family, but because it is possible to discover a freedom of spirit in which the boring job doesn’t matter, and without which anything they do will be empty.

Very edifying, J C.! Thanks.

I love this:

It’s a paradox because it’s a seeming contradiction. Like many other paradoxes, it is only a seeming, and it is only that because we are foolishly looking in the wrong place for ourselves.

The self is not a monad, sufficient unto its self for its selfhood. It exists in a physical, temporal, communal, and spiritual place. The individual’s identity is defined in large part by the body and by connections to family, friends, and God.

So there’s been some interesting discussion between Midge and J Climacus, with both of whom I wanted to agree, and probably managed to actually agree more often than not.

But probably not always. Instead of scouring all the relevant comments to figure it all out, I’m going to hope that my memories can identify just one of the big issues. I’ll state it, link it to some big names I know, and maybe even state some opinion on it.

Midge: Factors outside of our control matter; a person can fail due to these factors.

J Climacus: All that matters is doing our duty; obedience to our duty is entirely within our control, and thus failure in what matters is entirely free from the influence of external factors.

Midge’s thesis is associated with Aristotle, and J Climacus’ with Kant. Those are two of the biggest and best moral philosophers in human history.

Continued later:

Ah. Whereas I, though I was expected to be ambitious, internalized early on that I should not focus on myself and my own dreams too much. I should be humble, not thinking too highly of myself, even of real talents.

We can question whether I learned real humility, or instead that parody of humility that leaves smart men thinking they’re dull and beautiful women thinking they’re ugly, or however CS Lewis put it. Anyhow, the result of that “humility” was too little ballsiness, for lack of a better phrase.

There is a brashness appropriate to youth that I successfully unlearned at an early age, and one needs no unfulfillable fantasies about the perfect career to realize that lack of boldness can hold you back, even in a very ordinary life. To be bold enough to try things on for size, to boldly leave them if they’re not a good fit… some of that, especially during youth, is proper for securing a niche in the world.

It’s funny how often, when we talk to others, we lapse into talking to our former selves, urging others not to repeat our own mistakes :-)

Continuing from comment 77:

Interestingly, I think Midge and J Climacus and I are all Christians–would all fall somewhere within the bounds of a good generic statement of faith like the Nicene Creed. So which of these non-Christian philosophers are we supposed to agree with? A good question, and I’m not sure I know the answer. Any of these strategies seems ok:

Yes, that kind of falling-in-love still happens. At least it did to me. And for me, the love I fell into was of the doomed kind. It could not work because of mismatched moral expectations, or, in the most enduring case, because we were simply too crazy to be together.

Considering that one of the recently-despised prospects I faced was of, um, being a kept woman, it was right that I continued to despise it. But I won’t lie: it’s not easy reining in a heart ready to throw everything aside, including one’s sense of right and wrong. Still, it had to be done. Ouch!

Then at last there was my husband. He had fallen in love. I hadn’t, not at first. Too wary. But he did finally win me over, and I’m glad he did. Was it just months or weeks before engagement, or some time after marriage, that I had fallen completely in love? I can’t be sure.

Of course, there’s reason to believe men and women should differ in this.

And now that I’ve suggested these fine approaches, I shall ignore them and do something different.

Let’s look at the question again. What exactly is the disagreement over here? Note that there are not one but three topics to consider:

On the first two questions there is not really any disagreement between Kant and Aristotle, for they are talking about different things–as philosophers, including Kant, have noted before. Aristotle is talking about happiness and the proper functioning of the human person, and Kant is talking about moral law.

I think it’s safe to say that Kant is right about what he is talking about, and Aristotle is right about what he is talking about–a possibility to which Kant offers no objections at all. So Aristotle is right that factors outside our control affect our happiness, and even affect the health of our souls. But Kant is right that whether we do our duty is not affected by any external things.

So what about what we should seek, what we should care about? Should we be content if we have done our duty even if we end up as miserable failures in our jobs, or even if our spouses leave us, or our kids all die?

Now that’s a hard question.

Continued:

(Continued)

Answering in the affirmative, I think, we have the Stoics, but not necessarily Kant. And among Christian ethicists Boethius leans that way in his Consolation of Philosophy, along with (probably) C. S. Lewis. And I think we can find some strong biblical support for this, such as Paul considering himself accountable to God alone and not worrying what others think about him and not worrying if his efforts are even successful. And there is definitely an insight here: As long as I do my duty to my wife and job and kids, I should be content even I’m not particularly adept and useful at my job.

But I think Augustine–the real one–won’t let us go too far in that direction. In City of God we can’t be happy in this world because of all the sin and suffering–and they matter. Happiness is incomplete until the Messiah returns and sets things right. Neither will Scripture let us go too far in that direction. We have to care about those who matter to us, and Paul longs for the lost Jews to accept their Messiah. Even Boethius won’t go all the way with the Stoics–ignoring the things outside of our control when assessing our own happiness. Happiness is not complete unless the whole thing is complete.

Does this mean Midge is right and J Climacus is wrong, or vice versa, or that they are both more or less right, or that a compromise is necessary? I don’t know. I think I’d have to go back and carefully study all their comments to know; it could take quite some time.

But I think it does mean that we should limit somewhat our desires for things outside our control–but we should not limit them too much. On this question, at least, a compromise is appropriate.

Hopefully, both J Climacus and I were making good points, but from different perspectives. At least, that’s what it sounds like to me.

This thread needs to merge with Majestyks on how the secular lead meaningful lives.

We won’t be content, but the real question is whether will despair in such eventualities. And the possibility of such despair may prevent us from risking anything in the first place.

Kierkegaard talks about the leap out over 70,000 fathoms of water. What he means is risking ourselves in things like marriage and fatherhood, in which we commit ourselves fully and unconditionally, without knowing how things will turn out, and in full knowledge that we are making ourselves vulnerable and could be badly hurt. It is the knowledge that, with a wife and three kids to support, I may have no choice but to endure the job I hate. Or that, after enduring that job for 20 years, my kids might end up hating me anyways. Or dying in a car crash.

So do I not have kids in the first place to preclude that possibility? Kierkegaard would say this is already to give in to despair and to evacuate your life of true significance. Then what allows us to actually make the leap? It is faith in God, and trust that He will support us whatever may come. I don’t mean he will prevent…

… bad things from happening. But that, should they happen, He will provide me the grace to endure them and not be crushed.

So when I say a vocation cannot fail as long as we are faithful to it, what I mean is that our life cannot fail to have a significance and gravity it would not otherwise have, whatever the temporal outcome. It is to fight the good fight and understand that the battle was worth fighting even if I lost. More than that, it is the knowledge through faith in God, that as long as we are faithful in taking up our cross daily, the final battle is already won for us, and we cannot ultimately lose no matter how bleak things might look at any moment. Will such faith sustain us? We cannot know a priori, but only have faith that it will should the crisis come.

Pace Salieri, without faith in God, there is a temptation to risk less existentially speaking, I think. This is not dispositive of the secular life but I think it is a real danger, and explains why so many men (in particular) in our increasingly secular culture are frankly, in my opinion, wimps unwilling to shoulder responsibility like a man should. (That should get the comments rolling!)

You really must post these things when I’m not at work…

Hesitant though I am to contradict Augustine (either of them), I do not concur with this view of Ancient Happiness, if we think of Happiness in the same euphoric terms as moderns. Only the Epicurians could plausibly be compared to modern Utilitarians, and even then it is a stretch.

Consider the story of Alexander, who conquered the world, and wept for there were no more worlds to conquer, of Caesar who conquered the world, and wept that he had done so older than Alexander. And finally consider Augustus who knew that to conquer the world was nothing -to rule the world was the challenge. Only Augustus was happy, though all of them had satiated their desires.

Happiness to the ancients comes from excellence, from virtue. It was the ambition of Caesar and Alexander that made them unhappy, and no level of euphoria would fix that. Augustus, though, had no less ambition, but he had the sense to channel that ambition into the rule of the Empire, and through that, achieved happiness, even if he never achieved the euphoric highs of Caesar and Alexander. But the Ancients would still have called him happy.

Is simply accepting, and living with, the want — i.e., not changing desire, and not trying to change the world either — one of the sub-options of #1 or #2? Or, is that simply outside the scope of your premise?

(BTW, I’m not suggesting this as a way of life, or suggesting it’s even possible; just covering bases.)

Dumb question, but perhaps one worth asking:

If the ancients did not distinguish happiness from excellence, why not use the same word for both, either in the original language or in translation?