Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Raptors and Sheep in the Nihilistic Age

Raptors and Sheep in the Nihilistic Age

Over a year ago, I watched a talk by Joseph Bottom on his book, The Anxious Age. In that book, he argues that the decline in Mainline Protestantism has forced Americans — swimming as they are in Protestant Ethics — to seek the salvation they know they need in non-institutional, and therefore radical, settings. His focus is on the Left, and how the decline of the Mainlines has left them only things like radical environmentalism and Occupy Wall Street in which to work out their salvation through fear and trembling. However, he also argues that the rise in Catholicism and Evangelical Christianity is from the same source.

Over a year ago, I watched a talk by Joseph Bottom on his book, The Anxious Age. In that book, he argues that the decline in Mainline Protestantism has forced Americans — swimming as they are in Protestant Ethics — to seek the salvation they know they need in non-institutional, and therefore radical, settings. His focus is on the Left, and how the decline of the Mainlines has left them only things like radical environmentalism and Occupy Wall Street in which to work out their salvation through fear and trembling. However, he also argues that the rise in Catholicism and Evangelical Christianity is from the same source.

He argues that we live in an anxious age where people still need to know that they are good people — following in the Protestant Ethic that the saved can know they are saved because of their works and success — but that they lack the institutional forms, in whose membership provided they found confidence. “I’m a Methodist, therefore I’m a good person” is no longer adequate both because there are so few Methodists left and since being Methodist has so little meaning as the denomination drifts in the theological currents.

He recounts observing the environmentalists and Occupiers and hearing their language and their descriptions — their desire to be righteous — and concluded this is a religious belief. Unfortunately for them, he argued, because they lack someone who can tell them that they are saved, they will be forever anxious. However, this is a, as he put it, “thick” metaphysics about the world.

For the past year, I’ve been thinking about this talk off and on, gradually turning against it. I am tempted to directly compare the thesis to The World is Flat, that when Bottom listens to these Occupiers and uses their comments to ruminate on righteousness, I want to respond, “he said ‘brave’, not ‘righteous’; the two concepts are completely different.” In a more reflective moment, that is probably overboard: Friedman can barely speak modern English, whereas Bottom begins his lecture by reciting Everyman in Old English. However, I remain convinced that Bottom is wrong, on a metaphysical and philosophical level, about modernity. We do not live in an age where people worry about their salvation — an anxious age of question righteousness — but in an age where people worry about meaning. A nihilistic age.

Nihilism is a philosophical concept that, I imagine, is not well understood. It suffers by association with Nazism, but it also suffers from coming at the end of a Modern Philosophy or Philosophy of Ethics course. My formal Nihilism training begins and ends with “On the Genealogy of Morals,” and that was half a week in a modern political theory class. Put another way, a teacher can spend great gouts of time on Mill and Bentham, Kant can be his own class. Or they can talk about the proto-Nazi and spend half their time explaining that, no, Nietzsche was not a Nazi, he though anti-Semites were suffering under the same delusions as everyone else… and even your eyes are glazing over, so how about more Categorical Imperatives?

Consider language, an area a bit easier to understand. In The Lord of the Rings, knowing the true name of something gives someone power of that thing. When Legolas strikes at Gollum on the great river, shooting an arrow at him while the rapids buffet their boats, he cries “Elbereth Githoniel,” the elven name for Queen of the Gods, who created the stars. By calling on her by name, he adds power to his shot and quells the rapids, even though he misses. In the movies, this logic is why knowing the right words causes the phial that Frodo carries to light up. There are real things, and the names of those things attach to the real things.

Modern linguists and philosophers do not think this way, and — almost certainly — nor do most modern people. If there is a real thing that is the Queen of the Gods, “Elbereth Githoniel” is nothing more than a signifier of that thing, and it could be signified as easily by calling it “EG” or “Lizzie.” Words, by themselves, have no meaning, let alone any attachment to material things. The Queen of the Gods is “Elbereth Githoniel” because that is the name the elves gave it, and whenever someone wants to refer to her, they simply use that name because that is the name people use. It is convention. People understand the meaning because that is the meaning everyone understands, and those who use the word with a different meaning are not understood. Through trial and error and a certain amount of evolution, conventions ebb and flow, and the result is language as we know it.

This is what Nihilists mean when they deny the existence of real essences. Even “The Queen of the Gods” isn’t a thing, it’s a convention for discussing what may or may not be a lump of matter. “Queen of the Gods” has no meaning except to signify “that lump of matter, not this other lump of matter.”

When I say that an apple is red, I am not, contrary to all indicators, making a statement about inherent characteristics of the apple. I am saying that this particular characteristic is understood by all of us to be called “red.” Thus, it doesn’t matter if we all see the same color (though in a nihilistic sense, even this question is nonsense), so long as all people see the apple, however they perceive it, and all agree to call it “red,” then the apple is red. This is the appeal to convention.

When Nietzsche turned this analysis on morals, he saw that much of society, much of morality, has no metaphysical founding. How could there be when his very philosophical lens denied the existence of anything but material and convention? Society was rigidly ordered into hierarchies — not that it would matter if it were organized differently — but these hierarchies did not conform to anything real. When Aristotle talked of people with a “slavish temperament,” he was not describing a real thing, but a social convention.

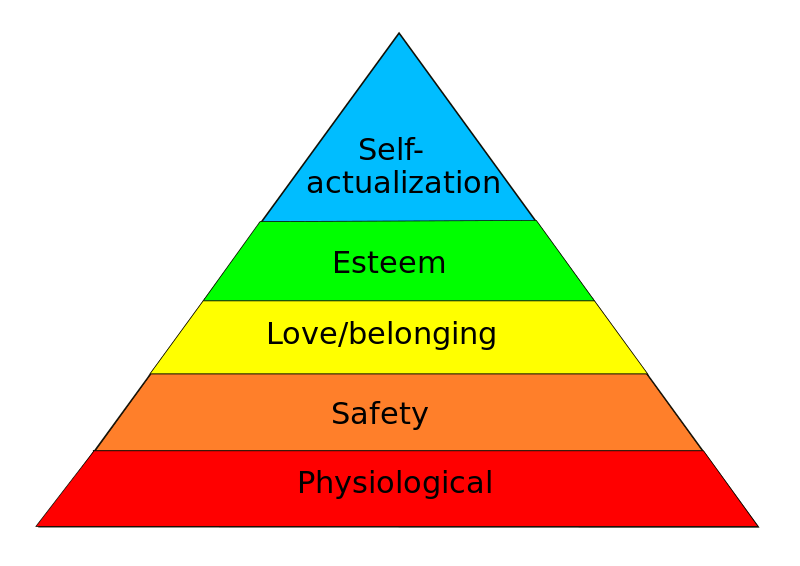

If we put that in modern terms, Maslow’s famous “Hierarchy of Needs” diagram, we would be saying that — insofar as this does not conform to purely physical things (i.e., the bottom two levels on the right) — then it is merely a moving through social conventions. People are self-actualized, free beings when they are recognized by other people as being self-actualized free beings. There is no actual difference.

If we put that in modern terms, Maslow’s famous “Hierarchy of Needs” diagram, we would be saying that — insofar as this does not conform to purely physical things (i.e., the bottom two levels on the right) — then it is merely a moving through social conventions. People are self-actualized, free beings when they are recognized by other people as being self-actualized free beings. There is no actual difference.

From this, it follows that morality — insofar as it lacks material attachment — is also merely conventional. The Feudal System morality was imposed by social convention, destroyed by social convention, and then replaced with Utilitarianism and Kantian Deontology, also by convention. Utilitarianism does not reflect a discovery, or a clearer understanding of morality than the hierarchical and martial morality of Feudalism, it reflected the rise of the middle class and the new importance that class placed — again, as a convention — on empathy and sensitivity, an emphasis Nietzsche ultimately blamed on Christianity (whose symbol was a crucified slave, and whose promise of comfort was that the crucified slave had felt your pain). Neither is better or worse, and both reflect what Nietzsche called the “slave morality,” both because of the Christian emphasis on the meek slave, and on how it reflected a convention hoisted on society by slaves.

In Nietzsche’s metaphor of the sheep and raptor the sheep — for their own protection — enforce a rigid morality upon each other of uniformity and empathy, and claim that their meekness and vulnerability makes them better than the raptor. The raptor then swoops down, seizes a lamb, devours it, and doesn’t care what the sheep say. The sheep call the raptor evil, but the raptor merely does what raptors do; it is a physical and material necessity, and the sheep cannot change that by adopting social convention.

Unless, that is, they can convince the raptor to adopt it, too. By Nietzsche’s time, he believed, they had. In a sense, Nietzsche is the anti-Socrates. Socrates looked at the people of Athens — so convinced that they were good people — and asked “Why are you good?” inquiring to Euthyphro as to why taking his father to trial for murder was a good act. Was it because the gods loved it, or was it good in its own right? What, specifically, made Athens good? Nietzsche asked the same question, “Why are you good?” but he asked a society that for two thousand years had believed its goodness, such as it existed, came from obeying a real command. (Christianity brushes off the Euthyphro dilemma by reference to God’s command, the Sole Creator of the Universe has decreed it. His universe, His rules. All else is commentary. Hence the importance Nietzsche placed on the metaphorical death of God). Absent that command, which in the world of Utilitarianism and the Categorical Imperative no had binding force, why are you still following it?

In X-Men 2, Magneto is a perfect example of the raptor in Nietzsche’s philosophy. When he asks a student for their name, the student responds with “John,” but that is the convention the student has followed. “What is your name,” Magneto asks again. “Pyro,” the student responds, holding a fireball in his hand. “You are a god among insects. Never let anyone tell you different,” Magneto says.

Even Utilitarianism and the Categorical Imperative fall to the moral equivalent of the “one less god” argument. The grounds for rejecting all other moralities applies just as harshly to these moralities. Why should we privilege empath, happiness, or logical consistency and collective well-being? We are raptors, not sheep. We make the laws, to our own advantage, and we insist that the sheep follow it because it is just.

The raptor binds the sheep because he is stronger. One what grounds can the sheep bind the raptor?

Nihilism is not morally vacuous, it is morally prehistoric. There is no morality, just the world of sheep and raptors, but because there is no morality, you can create your own morality if you have the strength to enforce it. You can create your own destiny, and — through your own will — create meaning. And if you cannot do that, you can hide in the herd of sheep and hope that the raptors come from someone else.

Confederate Monument in Perryville, KY

Under the old slave morality, in all its incarnations, each individual had a place in the world and could find meaning in their place. “Father” and “mother” were places where upholding the position carried meaning. “Employee” and “Employer” the same. When people fulfilled their obligations, they were feted and raised up above everyone. Not for nothing, but many of the memorials we have been talking about lately are spires with a dead man standing atop them. Perhaps I am drawing too much comparison if I remind the reader that the symbol of Christianity is also a dead man lifted above his enemies.

This insults the nihilist. Why is this nothing who did not create his own meaning, but sold his soul to the slave morality, worthy of a monument lifting him above mortal men? To the nihilist, humanity is a teaming mass of sheep, except for the handful of men who achieve self-actualization, the supermen who force, through sheer will, the world to acknowledge them atop their self-created spires.

Nietzsche did not envision, or did not separate from the “hide among the sheep” school, a third option. If the raptors’ created morality has rules that the raptors must follow, then the raptors can be bound by the sheep. Once a raptor allows any convention to dictate its behavior, it is at the mercy of the mob that decides convention.

Jonah Goldberg asked on a recent GLoP podcast how we ended up with the state of affairs on college campuses where students assert their will to power through displays of weakness. This is no strange affair at all. The raptors, or at least the strong sheep, accept the convention that weakness is a virtue, and thus these people flaunting their weaknesses are doing exactly what Nietzsche said the sheep would do. What would make them truly raptors is if they defied convention entirely -but so few actually are raptors. And many of the raptors still want to think themselves good.

It is for this reason that the people Joseph Bottom interviewed did not say they wanted to be righteous. Righteousness is a category of the slaves. They wanted to be brave. They wanted to be the primitive man demonstrating his value through the violation of convention. They want to be seen as raptors.

But they are not raptors, they are sheep who aspire to be raptors, and so they go about flaunting convention in a remarkably conventional way, and by setting new conventions for the flock, they think themselves raptors, or at least leaders among sheep. They create new conventions for everything, from sex to god, and think that makes them supermen.

They are not anxious about salvation, they are anxious because they know they pretend to be supermen when they are not. It is the anxiety of the con man and imposter. We know this because they want to be seen as brave. The true raptor cares nothing for what the sheep see.

The danger we face in the nihilistic age is that raptors still exist. And when they come, they do not draw distinctions among the sheep.

Kate Braestrup: #54 “Bonhoeffer—of whom we have spoken extensively—thought (and lived his thought) that just as Adam condemned all humanity through his sin, Christ reconciled all humanity in himself. There are many Adams (we are all Adams) but there is one Christ and, having appeared, redeemed all in him. All.”

Since Bonhoeffer was going to try to kill Hitler, it appears that “all” might be a misstatement of Bonhoeffer’s actual belief.

It has not been conclusively demonstrated that Bonhoeffer played a material role in the attempt to assassinate Hitler, FYI—not that it matters for the purposes of this argument: “All are redeemed” in soteriological terms doesn’t mean one human being can’t bump off another in the urgent here and now. Unless, of course, you are making my argument for me—that Bonhoeffer’s murderous intentions toward Hitler merely mirror his understanding of God’s murderous intentions (that is, hell) for whomever Bonhoeffer himself believed to be beyond the limits of the Great Commandment?