Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Raptors and Sheep in the Nihilistic Age

Raptors and Sheep in the Nihilistic Age

Over a year ago, I watched a talk by Joseph Bottom on his book, The Anxious Age. In that book, he argues that the decline in Mainline Protestantism has forced Americans — swimming as they are in Protestant Ethics — to seek the salvation they know they need in non-institutional, and therefore radical, settings. His focus is on the Left, and how the decline of the Mainlines has left them only things like radical environmentalism and Occupy Wall Street in which to work out their salvation through fear and trembling. However, he also argues that the rise in Catholicism and Evangelical Christianity is from the same source.

Over a year ago, I watched a talk by Joseph Bottom on his book, The Anxious Age. In that book, he argues that the decline in Mainline Protestantism has forced Americans — swimming as they are in Protestant Ethics — to seek the salvation they know they need in non-institutional, and therefore radical, settings. His focus is on the Left, and how the decline of the Mainlines has left them only things like radical environmentalism and Occupy Wall Street in which to work out their salvation through fear and trembling. However, he also argues that the rise in Catholicism and Evangelical Christianity is from the same source.

He argues that we live in an anxious age where people still need to know that they are good people — following in the Protestant Ethic that the saved can know they are saved because of their works and success — but that they lack the institutional forms, in whose membership provided they found confidence. “I’m a Methodist, therefore I’m a good person” is no longer adequate both because there are so few Methodists left and since being Methodist has so little meaning as the denomination drifts in the theological currents.

He recounts observing the environmentalists and Occupiers and hearing their language and their descriptions — their desire to be righteous — and concluded this is a religious belief. Unfortunately for them, he argued, because they lack someone who can tell them that they are saved, they will be forever anxious. However, this is a, as he put it, “thick” metaphysics about the world.

For the past year, I’ve been thinking about this talk off and on, gradually turning against it. I am tempted to directly compare the thesis to The World is Flat, that when Bottom listens to these Occupiers and uses their comments to ruminate on righteousness, I want to respond, “he said ‘brave’, not ‘righteous’; the two concepts are completely different.” In a more reflective moment, that is probably overboard: Friedman can barely speak modern English, whereas Bottom begins his lecture by reciting Everyman in Old English. However, I remain convinced that Bottom is wrong, on a metaphysical and philosophical level, about modernity. We do not live in an age where people worry about their salvation — an anxious age of question righteousness — but in an age where people worry about meaning. A nihilistic age.

Nihilism is a philosophical concept that, I imagine, is not well understood. It suffers by association with Nazism, but it also suffers from coming at the end of a Modern Philosophy or Philosophy of Ethics course. My formal Nihilism training begins and ends with “On the Genealogy of Morals,” and that was half a week in a modern political theory class. Put another way, a teacher can spend great gouts of time on Mill and Bentham, Kant can be his own class. Or they can talk about the proto-Nazi and spend half their time explaining that, no, Nietzsche was not a Nazi, he though anti-Semites were suffering under the same delusions as everyone else… and even your eyes are glazing over, so how about more Categorical Imperatives?

Consider language, an area a bit easier to understand. In The Lord of the Rings, knowing the true name of something gives someone power of that thing. When Legolas strikes at Gollum on the great river, shooting an arrow at him while the rapids buffet their boats, he cries “Elbereth Githoniel,” the elven name for Queen of the Gods, who created the stars. By calling on her by name, he adds power to his shot and quells the rapids, even though he misses. In the movies, this logic is why knowing the right words causes the phial that Frodo carries to light up. There are real things, and the names of those things attach to the real things.

Modern linguists and philosophers do not think this way, and — almost certainly — nor do most modern people. If there is a real thing that is the Queen of the Gods, “Elbereth Githoniel” is nothing more than a signifier of that thing, and it could be signified as easily by calling it “EG” or “Lizzie.” Words, by themselves, have no meaning, let alone any attachment to material things. The Queen of the Gods is “Elbereth Githoniel” because that is the name the elves gave it, and whenever someone wants to refer to her, they simply use that name because that is the name people use. It is convention. People understand the meaning because that is the meaning everyone understands, and those who use the word with a different meaning are not understood. Through trial and error and a certain amount of evolution, conventions ebb and flow, and the result is language as we know it.

This is what Nihilists mean when they deny the existence of real essences. Even “The Queen of the Gods” isn’t a thing, it’s a convention for discussing what may or may not be a lump of matter. “Queen of the Gods” has no meaning except to signify “that lump of matter, not this other lump of matter.”

When I say that an apple is red, I am not, contrary to all indicators, making a statement about inherent characteristics of the apple. I am saying that this particular characteristic is understood by all of us to be called “red.” Thus, it doesn’t matter if we all see the same color (though in a nihilistic sense, even this question is nonsense), so long as all people see the apple, however they perceive it, and all agree to call it “red,” then the apple is red. This is the appeal to convention.

When Nietzsche turned this analysis on morals, he saw that much of society, much of morality, has no metaphysical founding. How could there be when his very philosophical lens denied the existence of anything but material and convention? Society was rigidly ordered into hierarchies — not that it would matter if it were organized differently — but these hierarchies did not conform to anything real. When Aristotle talked of people with a “slavish temperament,” he was not describing a real thing, but a social convention.

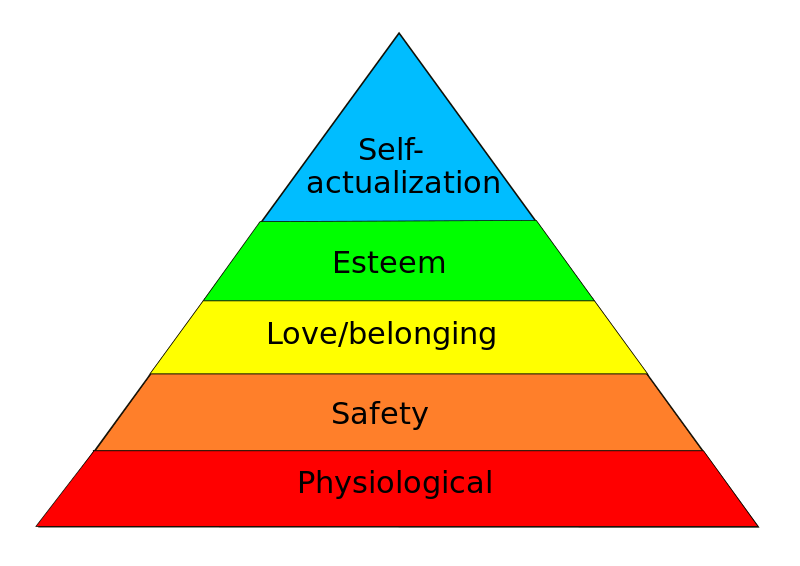

If we put that in modern terms, Maslow’s famous “Hierarchy of Needs” diagram, we would be saying that — insofar as this does not conform to purely physical things (i.e., the bottom two levels on the right) — then it is merely a moving through social conventions. People are self-actualized, free beings when they are recognized by other people as being self-actualized free beings. There is no actual difference.

If we put that in modern terms, Maslow’s famous “Hierarchy of Needs” diagram, we would be saying that — insofar as this does not conform to purely physical things (i.e., the bottom two levels on the right) — then it is merely a moving through social conventions. People are self-actualized, free beings when they are recognized by other people as being self-actualized free beings. There is no actual difference.

From this, it follows that morality — insofar as it lacks material attachment — is also merely conventional. The Feudal System morality was imposed by social convention, destroyed by social convention, and then replaced with Utilitarianism and Kantian Deontology, also by convention. Utilitarianism does not reflect a discovery, or a clearer understanding of morality than the hierarchical and martial morality of Feudalism, it reflected the rise of the middle class and the new importance that class placed — again, as a convention — on empathy and sensitivity, an emphasis Nietzsche ultimately blamed on Christianity (whose symbol was a crucified slave, and whose promise of comfort was that the crucified slave had felt your pain). Neither is better or worse, and both reflect what Nietzsche called the “slave morality,” both because of the Christian emphasis on the meek slave, and on how it reflected a convention hoisted on society by slaves.

In Nietzsche’s metaphor of the sheep and raptor the sheep — for their own protection — enforce a rigid morality upon each other of uniformity and empathy, and claim that their meekness and vulnerability makes them better than the raptor. The raptor then swoops down, seizes a lamb, devours it, and doesn’t care what the sheep say. The sheep call the raptor evil, but the raptor merely does what raptors do; it is a physical and material necessity, and the sheep cannot change that by adopting social convention.

Unless, that is, they can convince the raptor to adopt it, too. By Nietzsche’s time, he believed, they had. In a sense, Nietzsche is the anti-Socrates. Socrates looked at the people of Athens — so convinced that they were good people — and asked “Why are you good?” inquiring to Euthyphro as to why taking his father to trial for murder was a good act. Was it because the gods loved it, or was it good in its own right? What, specifically, made Athens good? Nietzsche asked the same question, “Why are you good?” but he asked a society that for two thousand years had believed its goodness, such as it existed, came from obeying a real command. (Christianity brushes off the Euthyphro dilemma by reference to God’s command, the Sole Creator of the Universe has decreed it. His universe, His rules. All else is commentary. Hence the importance Nietzsche placed on the metaphorical death of God). Absent that command, which in the world of Utilitarianism and the Categorical Imperative no had binding force, why are you still following it?

In X-Men 2, Magneto is a perfect example of the raptor in Nietzsche’s philosophy. When he asks a student for their name, the student responds with “John,” but that is the convention the student has followed. “What is your name,” Magneto asks again. “Pyro,” the student responds, holding a fireball in his hand. “You are a god among insects. Never let anyone tell you different,” Magneto says.

Even Utilitarianism and the Categorical Imperative fall to the moral equivalent of the “one less god” argument. The grounds for rejecting all other moralities applies just as harshly to these moralities. Why should we privilege empath, happiness, or logical consistency and collective well-being? We are raptors, not sheep. We make the laws, to our own advantage, and we insist that the sheep follow it because it is just.

The raptor binds the sheep because he is stronger. One what grounds can the sheep bind the raptor?

Nihilism is not morally vacuous, it is morally prehistoric. There is no morality, just the world of sheep and raptors, but because there is no morality, you can create your own morality if you have the strength to enforce it. You can create your own destiny, and — through your own will — create meaning. And if you cannot do that, you can hide in the herd of sheep and hope that the raptors come from someone else.

Confederate Monument in Perryville, KY

Under the old slave morality, in all its incarnations, each individual had a place in the world and could find meaning in their place. “Father” and “mother” were places where upholding the position carried meaning. “Employee” and “Employer” the same. When people fulfilled their obligations, they were feted and raised up above everyone. Not for nothing, but many of the memorials we have been talking about lately are spires with a dead man standing atop them. Perhaps I am drawing too much comparison if I remind the reader that the symbol of Christianity is also a dead man lifted above his enemies.

This insults the nihilist. Why is this nothing who did not create his own meaning, but sold his soul to the slave morality, worthy of a monument lifting him above mortal men? To the nihilist, humanity is a teaming mass of sheep, except for the handful of men who achieve self-actualization, the supermen who force, through sheer will, the world to acknowledge them atop their self-created spires.

Nietzsche did not envision, or did not separate from the “hide among the sheep” school, a third option. If the raptors’ created morality has rules that the raptors must follow, then the raptors can be bound by the sheep. Once a raptor allows any convention to dictate its behavior, it is at the mercy of the mob that decides convention.

Jonah Goldberg asked on a recent GLoP podcast how we ended up with the state of affairs on college campuses where students assert their will to power through displays of weakness. This is no strange affair at all. The raptors, or at least the strong sheep, accept the convention that weakness is a virtue, and thus these people flaunting their weaknesses are doing exactly what Nietzsche said the sheep would do. What would make them truly raptors is if they defied convention entirely -but so few actually are raptors. And many of the raptors still want to think themselves good.

It is for this reason that the people Joseph Bottom interviewed did not say they wanted to be righteous. Righteousness is a category of the slaves. They wanted to be brave. They wanted to be the primitive man demonstrating his value through the violation of convention. They want to be seen as raptors.

But they are not raptors, they are sheep who aspire to be raptors, and so they go about flaunting convention in a remarkably conventional way, and by setting new conventions for the flock, they think themselves raptors, or at least leaders among sheep. They create new conventions for everything, from sex to god, and think that makes them supermen.

They are not anxious about salvation, they are anxious because they know they pretend to be supermen when they are not. It is the anxiety of the con man and imposter. We know this because they want to be seen as brave. The true raptor cares nothing for what the sheep see.

The danger we face in the nihilistic age is that raptors still exist. And when they come, they do not draw distinctions among the sheep.

I took my second Great Texts courses from Dr. F. He’s good people. The stuff I learned in those Great Texts course helped me far into my graduate studies. When I was there he had his evil goatee though, so he looked much more menacing. Now he looks all friendly.

This is what I was getting at a couple weeks ago when I said the real problem is that moderns don’t believe in metaphysics. If there exists an eidos (ideal form or ideal world), then nihilism is just wrong, period, but so is utilitarianism and even Kantian deontology (not to mention logical positivism, but LP is wrong on its own terms), and only a virtue ethics based on the true metaphysics is possible. It is possible that a metaphysics could exist under which virtue ethics, utilitarianism, and Kantian deontology are all correct -it’s a metaphysics where sentiment=rationality=good=beautiful=true, which is probably where the Romantic philosophers were (certainly seems to under-gird a lot of Rousseau, the story of the soldiers returning to Geneva, for example).

But if we are all materialists, denying real things exist (in the Platonic sense of real), then there is no ideal to aspire to, and neither logical consistency nor sentimentality can substitute for the ideal because they are not real, either, and they also aren’t material. That makes them, at best, conventions (and now we understand what reason is the privilege of the overclass means).

Truly, we either believe in metaphysics or we believe in nothing.

Excellent.

But how can this rocket to the Most Popular box if we don’t have anything to disagree over?

Nothing big, at least; and I’m way too tired to wander off on a small tangeant, if indeed there is one.

We can always agree emphatically and at obnoxious length. Though I would think the following would be areas of exploration: does the metaphysical exist, can we prove or know that the metaphysical exists, is it true that the denial of the metaphysical requires a total denial of the metaphysical or can special carve-outs be given for specific concepts like reason or sentiment, and of course whether the denial of metaphysics actually entails the nihilistic ethic. Indeed, while I agree that Nietzsche argues that the best morality is the life affirming morality (whereby he dodges Plato’s argument that the strongest man is the greatest slave), the definition of “life affirming” is somewhat vague. Nietzsche hated the early-form Nazis, but the Nazis could reasonably have said that their morality was life affirming. It was affirming of the life and lifestyle of their particular race. Similar arguments made by the modern artist.

We could even ask whether Positive Liberty can exist in a nihilistic morality, or whether Negative Liberty can survive.

I have long said that a civilization in decline first loses the ability to memorialize events. Then it loses its ability to tell history. Then it loses the ability to tell stories at all. The great leveling of the nihilistic morality explains why. That may be another post of its own. (Also, why the WWII memorial is terrible.)

Did you have some examples in mind (other than the one with the lousy WWII memorial)?

Except that there were no sheep around when Velociraptors roamed the Earth, so we’d have to change it to the metaphor of the Velociraptor and the Protoceratops.

I was under the impression that because Neitsche’s heart would not soften that his head did and that he died insane.

It’s like he figured out Plato’s cave, went outside, saw the real world, then went back in the cave and blocked off the entrance and lied to everyone, telling them that there wasn’t a real world and that they we’re all going to die in there, so we might as well put back on the puppet show.

This analogy is mixed up; Nietzsche saw belief in the metaphor of the cave as a delusion. When you realize this, presumably the walls of the cave dissolve away, along with the puppet show.

To understand how he regarded the eternal recurrence, read The Gay Science 341:

The greatest weight: – What, if some day or night a demon were to steal after you into your loneliest loneliness and say to you: “This life as you now live it and have lived it, you will have to live once more and innumerable times more …” …

If this thought gained possession of you, it would change you as you are or perhaps crush you. The question in each and every thing, “Do you desire this once more and innumerable times more?” would lie upon your actions as the greatest weight. Or how well disposed would you have to become to yourself and to life to crave nothing more fervently than this ultimate eternal confirmation and seal?

To me at least, these lines suggest a higher demand for our actions than anything I encountered in Christianity.

Yes, he does say this in that little passage “How the True World Finally Became a Fiction”: We have abolished the higher world; so we’ve also abolished the lower world!

The nihilist can despair, thinking the world is gone. But Nietzsche really meant that we are now free to appreciate the world. It’s not that the lower WORLD is lost; what’s lose is the demeaning adjective LOWER in the phrase “lower world.”

Of course, those of us who know that there is a higher reality realize that the cave is not mere delusion.

Right. Of course, some of us think this remark is begging the question. But it’s all good.

I’ve been describing Game of Thrones as nihilistic. Glad to see that I haven’t been misusing the word.

Evidently not all that universal…

To worry about whether they are raptors or another brand of sheep misses the point of the names section above. Supposing they are sheep in a different herd; if they are still exerting their will to power on us it doesn’t matter that they’re not raptors.

These lines don’t make any sense.

Are we fated to repeat our life exactly the same way, making the same choices each time? If so, then free will is an illusion, so my apparent choices now carry no weight because the outcome was predetermined by what I did last time, and the time before, ad infinitum.

On the other hand if I really can chose how to live my life this time around, why shouldn’t I be able to choose a different path next time? If I have infinite tries then like infinite monkeys I’m bound to get it right eventually, so why be crushed if I make a hash of this go round?

The Christian idea that our choices in one mortal life determine our eternal destiny clearly carries more weight than either alternative.

Yes. Nietzsche derives the full logical consequences of his worldview.

First, Nietzsche believes that the belief in free will is an error. (He’s not the only one.) Second, you should reread the passage, which addresses the implications of “my apparent choices now carry no weight.”

What do you mean by “carries more weight”? Seems a better foundation for morality? Does a better job of molding people a certain way? Is more comforting?

Just to elaborate briefly on what I said, I regard Christianity as a simpler morality because it is founded on having the right fundamental belief. Individual actions carry less significance.

None of the above. I meant that individual choices carry more significance in Christianity than in Nietzsche’s eternal recurrence. If free will is an illusion then my choices are an illusion and thus carry no significance whatsoever.

In some ways the Nietzschean view is the more comforting one, as it frees me from the burden of agonizing over difficult decisions. Whatever will happen will happen regardless, so why sweat it?

In contrast I don’t see what’s so comforting about the Christian claim that Hell exists and I might end up there forever if I make the wrong choices in this one short life.

You are still importing your own interpretation onto determinism rather than reading Nietzsche’s account of it–which I conveniently provided for you.

In Nietzsche’s determinism, suddenly every moment of the day becomes fraught with concern over whether one is living life to the fullest. By contrast, once a Christian has accepted Jesus as his savior, he can take time out from prayer and contemplation to watch ESPN, fully comforted that his decision about Jesus has put him on the right spiritual road. The tough moral decisions–they are there, I agree–happen far less frequently.

(I’m assuming that most Christians today have moved beyond the theology of Jonathan Edwards.)

Assume again, J.D:

http://www.charismanews.com/opinion/50338-homosexual-normalization-is-it-time-to-embrace-god-s-judgment

7/1/15

Quote: Pastors who refuse to zero in on holiness, repentance and a clear and unapologetic revelation of hell and eternity should be ashamed and embarrassed to wear the title of “pastor.”

Where is the vivid, sharp preaching that divides and exposes the lies that are so pervasive today? Where is the Jonathan Edwards-style preaching that results in people feeling the heat of hell under their feet?

Incidentally, Jonathan Edwards preaching, back in the day, was said (by J.E. himself, among others) to have convinced people so thoroughly of their own damnation that they were led —by Satan, needless to say, not by the depression and despair induced by J.E.’s terrifying prognostications—to suicide. One might argue that successive Sundays spent before his pulpit could induce PTSD, especially given that he advocated preaching terror even to small children (the “young vipers,” as he called them).

If one wonders why New England is dotted about with lovely 18th and 19th century Universalist churches, here’s your explanation.

We read “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” in school. Do they any more?

They should! I don’t think I read it until I got to Seminary.

We read it in 11th grade American history.

Kate, Jonathan Edwards did get pretty heated in his efforts to convince people to accept their depravity in order to understand their deep need for God’s saving grace, but I think it is true that people need to hear that they are sinful. Maybe not in such an extreme way as that, but they need to hear it in a loving way while being reminded of the great hope of salvation. Universalism might have gained converts back then, but now it is losing them very, very quickly. People don’t go to church to have their heads patted, or most don’t. Like the naughty child who is really begging the parent to give him some rules, people go to church because they want to know how to live their lives, what to believe and how to find meaning in their existence. The church that believes in nothing, or just the general idea of “love” doesn’t give most of us what we want from religion. The emptiest funeral I ever attended was a Universalist one. At the time it struck me as less comforting than an atheist funeral would have been. Preachers should preach sin, and then they should temper it with the hope of repentance and salvation.

Weirdly, I agree with you, Merina! I do think preachers should preach sin, repentance and salvation. The only difference is what we are being saved from.

I think Edwards’ eternal torment is untrue, but more importantly,I believe it is counterproductive, even antithetical to the Christian project It gets in the way of love.

As I said in that long ago and far away thread on Hell, I have never, ever come across anyone who said that fear of Hell prevented him from doing something wrong. It does not prevent suicide even when suicide is presented as exactly the sort of sin that gets you damned. Incidentally, Merina, according to Edwards’ theology, you and I would almost certainly be doomed as the wrong sorts of Christian. (I would, of course, be honored to roast beside you, and promise to do my best to fan your brow. Maybe between dolorous groans and lamentations, we can share pix of the kids?)

A belief in the eternal damnation of Jews, Catholics, Muslims, Buddhists, New Agers, Universalists, Mormons, adulterers, thieves and unrepentant homosexuals…this is not, and can not be, a belief that inclines the believer to risk his own comfort, let alone his own life, for the physical safety and well-being of such people. Given human predilections, it can inspire violence. In the age of Isis, who really needs persuading that belief in a cruel God leads to human cruelty?

Universalism—the belief that all mankind is beloved by God— is not associated with an increase in immorality. In fact, in my reading of Christian history (especially recent Christian history) it is again and again strongly associated with an increase in moral courage. Having read volumes on the rescue of Jews during the Nazi era, for example, I have yet to come across a single rescuer who claimed to have been motivated by the doctrine of Hell. Many instead are quoted as saying things like “my parents taught me to love and respect all people, regardless of their religion.”

Bonhoeffer—of whom we have spoken extensively—thought (and lived his thought) that just as Adam condemned all humanity through his sin, Christ reconciled all humanity in himself. There are many Adams (we are all Adams) but there is one Christ and, having appeared, redeemed all in him. All.

Forget, for the moment, whether Bonhoeffer was correct. I’m more interested (as usual) in the result: if he had not believed this—if he had, instead, believed that some were unredeemed, that those outside the Christian church (even, specifically, outside his Confession) were condemned to eternal Dachau in the next life, how likely would he have been to identify himself with their suffering in this life, even unto death?

Kate, I agree with you that God loves all his children and that Christ’s atonement is for all. I also like C. S. Lewis’ point that God understands the heart, so that even those who do not understand these things still have the light of Christ and can make right choices and be saved. But I do think our behavior, our free will, our choices matter in this life. I certainly want to repent so that I can avoid hell. That’s not a place I want to be. Have you ever read Anne Douglas’ book The Feminization of American Culture? She argues that the move toward Universalism in the early 19th century led to a cloying and enervating sentimentality in culture and religious life. I think that’s where we are now. It’s all about feelings all the time. Feelings have their place, but people need more than that. They need God’s truth in order to know how to live their lives. Saying it’s all about love and that no matter what you do you’ll be saved just doesn’t cut it. Ironically, it just leads people to judge harshly those who do believe in truth and a moral code.

I agree, Merina. Modern culture is about feelings all the time. (Bleecchh). And it proffers on every side (including, at times, my own church!) a fundamental misunderstanding of “love” as a feeling rather than a decision, an orientation that demands self-sacrifice, responsibility and (therefore) offers joy. But that isn’t a problem specific to Universalism. Rather, it’s one of the problems of consumerism that has leaked into religious life—any church has the potential to fall victim, in various ways, to the temptation that spiritual life is not about God but is, rather, about me. My prosperity, my health, my pleasure, my contentment, even my salvation…me, me, me.

The challenge of liberal theology is to ensure that “love God/love your neighbor” is understood not as license but as the most demanding possible divine commandment, an obligation that one will spend a lifetime struggling to comprehend and live out, and yet the one thing that will give your time in this world meaning.

P.S. YAY! I love “talking” to Merina!

Well, if Christians really are back to “Sinners in the hands of an angry God,” then I suppose they will be just as discomfited from moment to moment as is the sincere believer in the eternal recurrence.

I didn’t personally witness much of this theology when I went to church, but times change.

I don’t think we’re back to that, but I like to go easy on Jonathan Edwards. He believed that people had to have a saving experience to truly be converted, and that people needed to be helped along the way in order to have them. No doubt some people were driven to extremes by his sermons, but he also brought many to those saving experiences. There was skepticism too, though, and that’s why he and his family were driven from Northampton. He’s an interesting person, no question, very intense in both his sermonizing, his worship, and what he demanded of his parishioners. Odd that he was the Grandfather of early republic bad boy Aaron Burr!

Anyway, Kate, I don’t think we’re that far apart in our thinking, but I do think we will be judged for our actions here on earth. Mormons have a bit of a compromise position about the afterlife. We posit three degrees of glory, each of which is good–good, better and best I guess– and better than this life, but the highest one is, of course, the best, and there you get to be with your family and loved ones forever. I figure that God is just and will sort everything out and be the judge. It’s just my job here on earth to try to figure out how He wants me to live and to live that way, especially to treat my fellow humans in the way I should.

I believe the Bible gives us rules for living, including the sexual code, not only for us personally, but so that we will be able to love our fellow humans without using them selfishly for our own ends. Because let’s face it, sex is one arena of life where people are famously able to convince themselves that what we want is what the other person wants. The Bible gives us a paradigm that tells us what is best for children and allows us to bring them into the world in a way that gives them parents and extended family and the very best chance to live a good and happy life. Without some pretty strong rules and mores, and those are pretty weak in our nation right now, that won’t happen as it should for the sake of the weakest among us.

We are definitely NOT that far apart!