Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Journalism and its Discontents, Part I

Journalism and its Discontents, Part I

Over the weekend, we had an interesting discussion on the Member Feed about journalism as a profession. Southern Pessimist asked me this question: “Give me some ideas,” he wrote, “of what you think needs to be reported that is not being reported.”

Over the weekend, we had an interesting discussion on the Member Feed about journalism as a profession. Southern Pessimist asked me this question: “Give me some ideas,” he wrote, “of what you think needs to be reported that is not being reported.”

My answer to this is so long that I’ll break it into a few parts. What should perhaps precede this post is a detailed historical account of what’s happened to the news industry since the end of the Cold War. I’ll come back to that, though, because the first point I want to make is that these changes have had significant consequences — largely, and surprisingly, bad ones.

So let’s in fact call this Part II. Let me begin by talking about foreign news coverage, since this is what I know best. I wrote this piece a few years ago: How to Read Today’s Unbelievably Bad News. Please do read the whole thing, but these are the key points:

Something has gone very wrong in American coverage of news from abroad. It is shoddy, lazy, riddled with mistakes, and excessively simplistic.

Above all, it is absent.

Many things are to blame for this. In 2009, I wrote a piece for City Journal observing the disappearance of international news from the American press. It is a long-term trend. A number of studies suggest a roughly 80 percent drop in foreign coverage in print and television media since the end of the Cold War. it seems to me—based upon my casual perusal of the American media—that the trend is accelerating. …

… In-depth international news coverage in most of America’s mainstream news organs has nearly vanished. What is published is not nearly sufficient to permit the reader to grasp what is really happening overseas or to form a wise opinion about it. The phenomenon is non-partisan; it is as true for Fox News as it is for CNN.

Yet this is odd. In the era of the Internet, mobile phones, social media, and citizen journalism, it has never been easier to learn about the rest of the world. So why have American news collection priorities changed so dramatically? What effect does this have upon American national security? The answer to the first question is complex; the answer to the second is simple: a bad one.

During the Cold War, every major American newspaper and television station covered foreign news, particularly from the Soviet Union and Europe. American television networks set the standard for global news coverage and — this is important — they drove the global news agenda. All the major networks had bureaus across the globe, staffed by correspondents who had been on the ground for years. Whether they were in Berlin, Cairo, Istanbul, or Moscow, they knew their region, they knew the people, they spoke the local languages, and knew the history of the stories they covered. …

In the Cold War era, US network news coverage was delivered worldwide: ABC fed Britain’s United Press International Television News, NBC fed Visnews, also based in Britain; CBS had its own syndication service. Few national news stations outside of the United States had the capacity to cover international news, but the United States did. During the final decades of the Cold War, for example, CBS had 14 massive foreign bureaus, 10 smaller foreign bureaus, and stringers in 44 countries.

CBS has since shut down its Paris, Frankfurt, Cairo, Rome, Johannesburg, Nairobi, Beirut, and Cyprus bureaus. The other large networks have downsized similarly. US news stations have decided that some places aren’t worth covering at all. We have almost no coverage out of India, for instance — disasters, yes, but nothing else. Likewise with Africa. As for the Middle East, we hear an enormous amount about Israel, but ask yourself what you’ve heard, recently, about Libya — a country where we recently toppled the government. Does it not seem odd to you that almost no one is reporting on the aftermath?

More than ever, news is reactive: There is no coverage before a story breaks, even if people on the ground could have spotted it coming a hundred miles ahead. So Americans are shocked when an emergency occurs overseas (or, for that matter, at home, as on September 11) — because they had no idea it was even a situation.

In the event of a massive breaking story — such as the uprisings in Tahrir Square — the networks parachute their people in. They bone up on the story by reading the local English-language newspapers (and in any country where English isn’t widely spoken, it is important to ask: Why does it have an English-language newspaper? The answer, usually, is that the paper is trying to sell a particular version of local events to investors and to English-speakers — a version, needless to say, that is not necessarily the whole truth). In this scenario, the US correspondent functions as a talking head: He repeats the locally-produced news story in front of a camera.

In other words, the pattern has now been reversed. Whereas local news stations once relied upon American networks for global coverage, American networks now rely upon local news services for their global coverage. Many dedicated and talented freelancers pick up some of the slack, but there is no substitute for the support of a fully-staffed local newsroom with collective decades of institutional knowledge — and as someone who has been trying to earn a living as a freelancer for many years, I can promise you that the job insecurity is enough to discourage many talented people.

According to the American Journalism Review, at least eighteen American newspapers and two chains have closed every last one of their overseas bureaus since 1998. Other papers and chains have dramatically reduced their overseas presence. Television networks, meanwhile, have slashed the time they devote to foreign news. They concentrate almost exclusively on war coverage — and then, only on wars where US troops are fighting. That leaves the big four national newspapers — the Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Los Angeles Times — with independent foreign news coverage. But they too have closed foreign bureaus in recent years. In 2003, the Los Angeles Times shut down 43 percent of its foreign bureaus. This is especially significant because the Los Angeles Times provides foreign coverage for all the Tribune Company papers.

But couldn’t this be seen as a good and inevitable thing? Aren’t local news services inherently more qualified to provide this coverage? Isn’t it obviously more cost-effective to rely upon them? Yes, and no—but mostly no.

First, the system has not yet been replaced by a platform of highly-competent local news agencies that share a commitment to the basic codes of journalistic conduct that even the sleaziest of American papers take for granted — by this, for example, I mean that one shouldn’t just make up quotes, or grossly alter them to change their meaning, and that one should at least try to confirm rumors before reporting them.

Second, there is little diversity. Without much exaggeration, we can say that Al-Jazeera has replaced American television news as the global driver of the television news agenda, and not only in the Middle East. Al-Jazeera’s coverage of Cuba, for example, is unexcelled by any American media outlet. Compare its coverage over the past year to CNN’s, for example. But Al-Jazeera is Qatar’s foreign-policy arm, not ours …

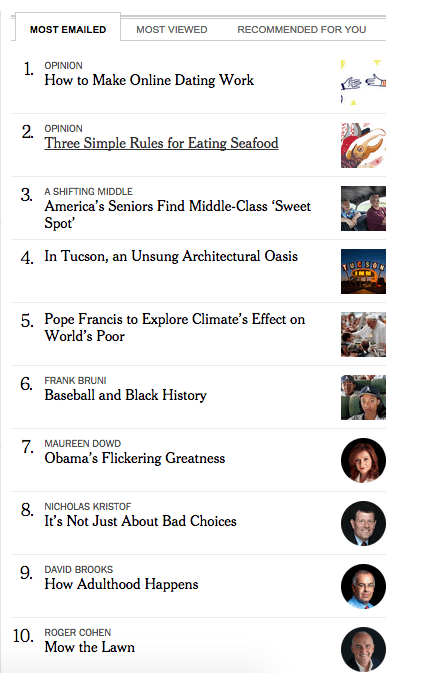

… So what’s happened here? For one thing, the Internet and other technological revolutions in news gathering have resulted, to put it simply, in giving consumers who are in no position to determine what’s newsworthy too much power to decide what they think is important. News consumers may now customize the news they receive to an extraordinarily high level of precision and ignore everything else. Because stories are no longer bundled together in a single physical item — the newspaper — the reader no longer has to slog through, or at least cast his eyes over, stories about high-level meetings on nuclear disarmament in order to get to the sports page. We choose each item with a mouse-click—bye-bye, P5+1, hello, Jerry Sandusky.

News producers rely increasingly on independent companies to sell their ads; they are now dependent upon aggregators (such as Google) and social networks (such as Twitter) to bring them a large part of their audience. Consumers read stories that interest them; the aggregators, noticing that a consumer liked a story, offer them more of the same — stories, in fact, as similar as possible to the ones they just read. Obviously, readers end up having their biases confirmed this way, rather than being exposed to stories that might disconfirm them.

Similarly, sharing stories on Facebook and Twitter means, by definition, receiving your news from people who have been pre-selected to be very much like you in their political instincts — but not people who have been pre-selected to be good news editors. …

The people who understand how to target content and advertising to fit users’ interests are not foreign news specialists. They’re software programmers and technology companies. Most wouldn’t recognize a significant foreign story if it bit them in the ass. …

We are in a recession, and Craig’s List killed the advertising model for local newspapers. Local papers no longer have the resources to pay for foreign correspondents and their housing and their staff. It’s easier and cheaper to run wire-service stories. It makes perfect economic sense for local papers to focus on local news. But obviously, the reliance on wire services grossly reduces the diversity of reporting and reinforces the echo-chamber effect—it’s all Pussy Riot, all day, and it’s springtime or a nightmare in the Arab world, and who knows what’s happening in China, not me, for sure. Nor is the slack being picked up by bloggers: Their domestic focus is almost identical to that of the mainstream media, suggesting that the mainstream media is still driving the agenda.

This is not solely an American problem, by the way. A report titled “Shrinking World” published by the Media Standards Trust suggested that international reporting in UK newspapers has decreased in the past 30 years by nearly 40 percent. Let me point out a particularly disturbing line from that report: “In such a setting, it’s no surprise that UK-based correspondents rely on news sources from the country of origin as well as newswire content like that provided by Business Wire to fill in the gaps, turning the loss of foreign correspondents in UK newspapers into a gain for PR professionals and their clients.”

Let those words roll around in your mind—”a gain for PR professionals and their clients”—and think about what that entails. What it entails is this, as I’ve noted before:

‘Wikileaks is at it again, this time, leaking a (promised) two million-plus emails from the Syrian regime, which has in the past eighteen months tortured, raped and killed at least 15,000 of its own citizens. And look what we have here: A memo explaining how to get away with it from Brown Lloyd James. …

I believe I’ve quoted myself enough. If you’d like to read the rest of that piece, please do; I think there’s quite a bit that’s important to grasp in it. Since I wrote it, the situation hasn’t improved.

Part III will be another post: I’d like to give you a detailed account of what I saw in Turkey that was never reported. Anywhere. I’ll explain why this mattered so much. But that will have to be for another day, lest this be too much to digest.

Having left Turkey, of course I regained some perspective. It is not really so surprising that Americans don’t find themselves fascinated by the minutiae of (seemingly) internal Turkish political power struggles. I paid attention as if my life depended on it, but that was because it did. Absent such motivation, sure, it all looks rather boring. I used to assign to that general inattention some kind of moral importance. I recognize that now for the cognitive distortion it was. I confused myself with the center of the world. It happens.

But that doesn’t mean there’s not a problem. In the worst-case scenario, the conclusion I might draw is that I’m not a writer of talent sufficient to make an interesting story interesting. (If you’ve read this far, you can assess that hypothesis yourself. Let’s assume that’s a possibility, but set it aside for a moment for the sake of the argument.) But in the next-worst case scenario, the free world can’t survive. Now, my narcissism might not be of such importance to you, in which case you may reorder the priority of worst-case scenarios.

I have a strong sense, and in many cases evidence, that our disastrous foreign policy is connected to what’s happened to the way we receive our news. I am not quite sure in what way, or in what order of priority. But in my worst fears, it involves a contradiction in the idea of a free society.

Here is where things become inchoate, and where your thoughts might be useful. My own career seems to me a case in point, but that’s exactly why my thinking about this is suspect. Still, my career suggests there’s a problem that involves “How to get the money,” versus “How to do the kind of reporting I think should be done.” And some part of the answer has to involve thinking about this: You can’t shove a story down peoples’ throats. You have to make it entertaining, and you have to make it fit whatever the revolting term “narrative” implies.

The only alternative is coercing Americans to read the news in a way that’s incompatible with any ideals we might still have about living in a free society. Forcing people to read the news? That’s obviously out. State-controlled media? Ixnay. But if you can’t entertain your audience or satisfy their need to believe what they want to believe, you can’t sell it.

And if you can’t sell it, too bad. That’s life in a liberal democracy with a free market. And this too is a principle in which I deeply believe.

As far as editors are concerned, their first priority is to stay in business, so that story has to make readers want to read it. A journalist must be able to deliver a coherent and entertaining “narrative,” and do it every single day and on a deadline. Someone who does it four times a year, or turns it in 20 minutes too late, is no use. So already, you’ve got a very narrow pool of people with the real skill set needed, and no demand for the kinds of stories that I suspect people really do need to understand. Can this readily be exploited by sinister people? It can be. Is it? Yes. I promise you, it is.

But does this matter?

That’s the key question. Perhaps it all balances itself out. The sinister have no more luck getting anyone’s attention than the well-meaning. And it does seem important evidence that we’re still here, even though it seems to me as if this is a vulnerability so huge you could drive a Mack truck through it (or planes right through the Twin Towers, for that matter).

It wasn’t until I lived in Turkey that I began to notice a hugely significant disjunct between “what was reported” and “what was around me.” Of course I’d seen such things occasionally, but enough to chalk it up to “bad reporting,” as opposed to “systemic flaw.” Now I notice it in everything I read. Everything.

One thing is clear to me: We know thanks to a number of leaks (of which I disapprove wholeheartedly but nonetheless studied carefully) that good reporting can be done. The employees of our State Department are not nearly as stupid and credulous as the editorial board of The New York Times, for example. (Still a bit stupid and credulous, from the looks of it, but not that stupid). And their ridiculous marketing aside, Stratfor seems to have quite a reasonable handle on things. So there are people producing the kinds of reports that should be produced, and someone, somewhere is able to read them.

But surely they’re not the only people who need to know? The idea of democracy is quite hollow if we think so, isn’t it? And this is a special problem in foreign policy, where there are huge disparities of power between nations, and where even a well-meaning superpower is capable of blundering spectacularly. If the public has no understanding of what we’re doing or the effect it has on other countries, it can’t reign in the people and organizations making our policy. State and Stratfor may be able to produce a higher-quality internal product, but it isn’t designed for the purpose journalism is supposed to serve. Journalism is at least supposed to tell the people (as in “We the People” — anyone remember us?) that “This is the effect policy X has on country Y, and the effect such a policy might have on you, and you thus now have enough information to decide whether you approve, and vote accordingly.” Right now, it does no such thing. Not as far as I can tell.

This lack of accountability and oversight — surely it has consequences? The founders of our nation thought about problems like this. My guess is that this does, of course, affect us, if only more slowly than we realize. It certainly affects people in countries affected by our superpowers, who don’t get a vote on US policy.

Even with the passage of time and some perspective, I can’t escape the feeling that it matters very much that Americans don’t understand, if only in outline, the story of our involvement in Turkey and what has happened there in the past decades — and understand, too, that this happened in some part as a consequence of our decisions.

Turkey is a more limited case. But there are vastly more spectacular cases. It matters when Americans don’t know enough to stop their government from, say, turning Libya from a garden-variety menace into a dangerous failed state. Or even realize that this is in fact precisely what we did. It matters a great deal that Americans don’t realize, generally, that in all matters of foreign policy, their government must be watched like a hawk — and we must watch it just as closely as we would watch it in matters domestic.

But.

Here is where I run into a bit of an epistemological crisis. I don’t know how it would be possible for us to watch it that way. It seems to me that’s genuinely impossible, to the point of being logically impossible. Who on earth, with a normal life, a job, a family to support, could follow all of this in the requisite detail? And if it’s impossible, what does that say about the entire American project?

You can see where this train of thought becomes grim. The modern nation-state with universal manhood suffrage is still quite new. There’s really not much with which to compare this state of affairs. But the degree to which Americans are indifferent to foreign news is new, and demonstrably so.

I’m not arguing that the root problem is that journalism has changed. Perhaps the reasons for this change are more important to consider than the fact of it. Perhaps it’s a symptom, in other words, not a cause. But whatever the deeper cause, this is a problem that may, perhaps, have a solution. I haven’t yet figured out what that might be — but that only means I haven’t figured it out, not that it doesn’t exist.

So let me put these thoughts to you first, for discussion, because this is already very long. Tomorrow and the next day, I’ll write more about the history of these changes in the news industry and about the specific case study of Turkey, because it’s very compelling evidence for my argument that yes, it matters when important stories aren’t reported.

Then I’ll get to Southern Pessimist’s questions. I’ll tell him both what I think the top reporting priorities should be — in an ideal world — and what I think I could do, on my own, if only I had a budget in which to do it. On the next day, we can discuss domestic news coverage — obviously just as much of a problem, albeit with some different features. So it will be a long week, alas.

But perhaps if we all give this some thought, we’ll come up with some good ideas together.

Published in Foreign Policy, General

Yes, I think they were. Partisan, to be sure, but doing more reporting.

Is there a market for a Ricochet Global Podcast, with segments each week from top correspondents around the world? Maybe get one of the travel websites, some airlines &/or hotel chains to drop ads in between segments for additional support?

Never seemed right that NPR has this territory pretty much to itself in the U.S.

Claire,

You journalistic tease. Here I was up all night worrying about you. (OK I thought about it for 5 min while I was hanging up my shirts.)

How thoughtless!

Regards,

Jim

The Internet should not seem to cut in that direction. If information is a cheaper product, it should be easier to get high quality information too cheaply. A little more sifting through the chaff, but it shouldn’t be impossible to find good aggregators to do some of that. MEMRI does something like that in its limited way.

Cheaper information makes certain kinds of newsgathering prohibitive, like foreign bureaus. But even if they were not so expensive, is there really a demand for the work that they do? There is certainly a need, but any real desire?

Some days, it seems like there is a world with so many things going on, more countries than ever and more problems. And it’s hard enough to get through day as is. For a lot of people, it is easier to let it go until the problems get to the doorstep.

We are witnessing the same revolution that the printing press did to Church controlled writing by monasteries. The intermediaries are losing power as the technology allows wholly different groups and individuals to disseminate information and opinions.

Information dissemination has never been separated from opinion in any media ‘golden age” . What was written or not written always came from the opinions of the journalists.

Yes, it is messy, and yes, people are parochial.

And yet, in the world the journalists rarely cover as leading news, where things are actually happening that will remake the world, in laboratories and factories, in obscure regulations and remote mining camps, specialists have networks that convey facts and make decisions based on them.

It may no longer to possible to know enough to be a ‘well informed citizen of the world’ but we all may know our piece of it.

BTW- I would rather watch a hippo wandering through Georgia than listen to anybody from the State Department on anything.

Hasn’t there been significant growth in the number of political “pundits” and news commentators? You are one of them, Claire, as are many other Ricochet contributors — Robinson, Epstein, Yoo, Goldberg, VDH, Williamson, the list goes on and on. It seems that the market has generated a niche for experts to pre-analyze the foreign (and domestic) news for us, and direct our attention to the important areas.

Now, how you can make money in such an environment is a different question. Many of the best commentators are associated with conservative or libertarian think-tanks which, I assume, are supported by donations.

I also wonder how much of the problem is decline in trust for the media in general. I’m not sure exactly when it happened, but the MSM is widely recognized as highly political. I am very skeptical of news reports from the NYT, WaPo, LAT, ABC/NBC/CBS, and most other outlets, which I view as quite left wing. I remember a joke about the debate programs shown in Europe — say their equivalent of Special Report with Bret Baier — in which the breadth of debate runs from the left, to the far left, to the looney left. I think that NYT, WaPo, LAT, and the 3 networks are closer to the far left than to the left. Ditto for CNN, with MSNBC approaching (and sometimes entering) the looney left category.

But, but. Tbilisi’s hippos will never say anything as…entertaining…as John Kerry’s remark that in America, everyone has the right to be stupid.

Eric Hines

I have a strong sense, and in many cases evidence, that our disastrous foreign policy is connected to what’s happened to the way we receive our news. I am not quite sure in what way, or in what order of priority. But in my worst fears, it involves a contradiction in the idea of a free society.

As you warned, there is more in your post to consider and discuss than can be attempted in weeks or months of conversation, but I was struck by that quote above. I accept on blind faith that we have an intelligence community working on our behalf around the world keeping us safe. I suspect they share much of the conventional media bias but I don’t know that.Your quote implies that the people who are making our foreign policy decisions are either willfully ignorant or emboldened by the knowledge that Americans will neither care or ever learn about the choices they make. Very sobering. A free society cannot exist without free access to information.

I listen to BBC World News often to see what else is happening in the rest of the world.

I know they are biased but how else would I have learned about a flood in Pakistan last year? Imagine my shock when I heard a woman interviewed, “We are drowning here. Where are the Americans?”

The reality is 99% of Americans didn’t know there was a flood, much less that they were expected to help. I can see why some people in other countries think we are different than what we really are. It is sad that we have lost our interest in others.

*Side note—It is not the US’s responsibility alone to help. Pakistan has many closer and as wealthy national neighbors.

I don’t know, and there well might be, but I’ll come to this point in a subsequent post. What you’re suggesting is a form of aggregation, not reporting, and aggregating is a where it’s at, for a lot of people: Real Clear World is the best example. The problem is funding those top correspondents around the world so that there can a) be more of them (and good ones); and b) do more reporting.

Never seemed right at all, because they’re state-funded, and first, that’s inherently wrong — my taxes shouldn’t go to support that — and second, no matter how subtle, state-funded news always has a bias in favor of its financial backers. If you get your paycheck from Uncle Sugar, you can’t go too deep in your reporting of the part of any foreign-policy story that probably needs reporting most.

Yeah … I hear that all the time and it’s true. “I know they’re biased, but at least they’re getting us some news!” Way better than nothing.

Agree. But the US does have some very specific expertise that can be useful in situations like this, and I think most Americans are very happy to think of themselves as people who lend that expertise in times of trouble. They didn’t just need food and water, they needed river and flood management engineers.

I thought that story — about the zoo in Georgia — was a legitimate news story, worth covering, and covered well, but I couldn’t watch it because it broke my heart.

The pieces are longer there and have the sound of depth, though often with slant, especially the slant of what to cover in the first place.

But conservative radio, which is so much more extensive and profitable, doesn’t do the kind of reporting you’re talking about. Hewitt’s show is smart, but the others … not much depth. This morning Rush was on about Jenner, and not in a kind way. I’d have rather learned something about Turkey on the way home from the chiropractor.

Sure. Comes with the territory in a free press: You’ll get a lot of lousy reporting. But there’s no reason you shouldn’t also get a lot of good reporting, too.

Well, the numbers just don’t support that assertion. Before the First World War, that could fairly be said, maybe. But throughout the Cold War, if we judge by the number of journalists employed, bureaus abroad, and percentage of the news hole devoted to foreign stories, the United States consumed foreign news avidly. The (astonishingly) sharp dropoff began when the Berlin Wall fell, and now we consume almost none. That’s a very big cultural change, especially since we haven’t reduced our foreign footprint in anything like a commensurate way — and in fact have trebled our share of global trade since 1960, and still have a huge population of recent immigrants with families back in the old country.

True in the 19th century, but definitely not the 20th up to the end of the Cold War

I don’t have stats at my fingertips about how many of have family in the old country, but unless all 42 million immigrants now in the US are orphaned, I figure we still have a lot of them. And most of us are indeed doing business with foreign enterprises — even if it’s at several removes, it doesn’t change the fact that it’s a big part of our economy. I mean, if nothing else, every single American is very affected by events that cause the price of oil to go up and down.

And I don’t, do you? But my argument for reporting from abroad isn’t that we should all be exposed to their amazingly-equal cultures. (Maybe I’m misunderstand your point, though, so let me ask for clarification.)

Yes and yes. The solution is a business, not a government solution, and it’s out there –waiting for someone to figure out what it is and get rich and do good and serve our country while getting rich. I just haven’t cracked the nut of how to do it, yet.

Maybe as I share more this week, I can bring you around a bit on why this is such a big part of (what I agree is) the larger problem. Give me a bit more time and some patience. I have very specific case studies to present that show why it matters.

Not sure if this was asked earlier – but where should we be going to get actual global news now?

I’ll answer this at much more length, but quick tip: If you only have time for one site, Real Clear World is the best aggregator.

Albeit from a very specific editorial position – reflected in what they choose to cover and the words they choose to describe it. Would you say that their level of bias is substantially different from any other media house’s, or pretty similar?

I don’t doubt your expertise on this, but were they writing different things about it? Were they seeing it differently, or did they all bring a similar set of assumptions to the issue? That’s what I mean when I ask about media diversity.

Or to use another example, if you will permit it –I think it’s fair to say that the Islamic Revolution in Iran was something of a surprise to America and the rest of the West. I’m going to guess that most US papers had Tehran Bureaus. Smart, educated people –did they all miss it coming? What were they all looking at instead?

Does this drop off coincide with the(post-socialism post-doimoi) growth of media in other countries, and the growth of cable and satellite access to these? The amount of foreign news provided by US media houses is not necessarily a good measure of how much foreign news US residents consume if they can access and consume stuff directly from their area/country of interest.

The Indian media landscape today is unrecognizable from the one I grew up with. Overwhelmingly this is the result of private companies and overwhelmingly it is very good for the country – but it also means that Indians can move to the US or Australia and still get as much of their news and entertainment as they want from India via cable or satellite, and they’ll get it at as good a standard as they desire. It’s no longer less believable.

Aljazeera has, for whatever reasons, done something similar for the Middle East, and for a lot of smaller places which lack India’s critical mass.

One could say the same thing about (rotary dial) telephones, if we judge by the number of switchboard operators employed, etc.

Here’s a bit of inchoateness for ya…

I completely get where you are coming from Claire. And yet, I started to think back to before the Cold War days when foreign bureau’s were plentiful. Before then, news was slow and, when it did finally arrive, most of the time throughout history that news was hardly a description of reality. Party papers were in every city in America without a micron of ink spared for foreign issues, unless there was something big going on like the Maine sinking or an Archduke getting assassinated.

But those were the old days, when important decisions took days and taking actions based on those decisions took much longer. The times have changed.

Now we have the power to topple countries in weeks, if not days, and, lest we forget, we and many other nations have weapons that can topple lots of life in minutes. With great power comes great responsibilities.

Have we shirked our responsibilities by not keeping abreast of world news? Yeah, I guess. But when you give someone as Sisyphean a task as being knowledgeable about the world and all of its inhabitants I can see why they give up and turn on the Kardashians.

Heck, I consider myself more informed than the average American adult but the only reason I remember that the leader of Venezuela’s last name is “Maduro” is because I smoke a lot of cigars.

No doubt. But it happens. And it happens in just that part of journOlism that most closely touches upon democracy.

Let’s look at this from the other perspective: how is the US covered in foreign media? Lots of ‘serious’ news outlets have NY and DC bureaus, but can you think of a single correspondent reporting on the US who would really try to explain the politics of the Second Amendment (other than by referring to strange fetishists in former slave-owning states), or the opposition to Obamacare? As a foreigner you could consume the entire output of the NYT, WashPo, LATimes, CBS, NBC, ABC and CNN and not come across a single report that didn’t assume that gun control was rational and compulsory universal healthcare the only moral stance.

Here’s a challenge: find an editor of a serious news outlet in France – of whatever ideological stripe – that doesn’t believe Clinton was impeached for having sex, Bush didn’t carve a plastic turkey, and Palin didn’t say you could see Russia from her house.

Journalism is broken. Perhaps it always was. Accept that, and we can move to ‘solutions’. (:

Okay, here’s how I’d respond. I think that would in fact be an interesting question. I think it would be an interesting article to write. I’d quite like to know whether there’s an editor of a serious news outlet here who doesn’t believe those things. And it’s an empirical question, and probably one that would take me a month of (probably) full-time work to answer in a serious way. That’s how long it would take me to make contact personally with the editors of all the papers and outlets that we might reasonably define as serious, and interview them. Asking people who know them or know them by reputation would be faster; that I could get done in a week, I’m sure, but that’s a lot less apt to be really accurate (or fair) then asking them directly. I’d have to ask those things as non-leading questions, and figure out some way to do this that was reasonably methodologically okay.

I bet the answer — whatever it is — would be kind of interesting, and would have some value as a story: It would give us a sense of how public judgments about the US are apt to be shaped; France is quite an important ally in many ways, so this does affect us, and it would just be an interesting story to work on.

But would it be worth it to you to pay a reporter to work on this story, full-time, for a month? Seems a ridiculous waste, to me, priority-wise. Especially since there are a lot of other stories I could work on from here that seem a lot more relevant and that the media has just plumb forgotten about. For example: Anyone here have a vague recollection of something called Operation Serval? (Don’t look it up, just tell me whether you remember.) If you do, do you have any sense of how that went? If you do, do you have any sense about whether that might be quite interesting and relevant for Americans to think about? I have lots of questions I’d love to ask people (who are right here in Paris) about that.

Odd that this story gets zero, I mean zero coverage — after all, if what I’ve read about is accurate — and I’d have to confirm that it is, I don’t know — then France managed to pull something off that really warrants some thought, given that this is what your tax money was spent on (a failure, clearly). Is there perhaps something we should learn from how France did what they’re said to have done?

Now, that’s a story that might be worth someone’s money. Want to make it a much better story, though? Send me to Mali. Another month. But now we’re talking real money. (Although I’m sure my expenses would be much lower there than in Paris.)

So. You could have my opinion about this, based on what I’ve read and heard, and that would be nearly free. To most people it would sound pretty good, too. But it wouldn’t be a huge improvement on what you could do with Google.

Or you could have my reporting on it. In my experience, two months of reporting on anything unearths a lot of stuff that’s really nowhere to be found on Google. And my news instincts about the Operation Serval story say — I’d find out a lot of stuff that people really ought to know.

If you’re managing a publication on a budget, though, of course you’ll go with my opinion.

I can’t speak to this but I know that in 1981 when we moved to Louisville, KY, the Courier-Journal (morning paper) and the Louisville News (evening paper) were both owned by the Bingham family. Both papers sent reporters out to every incident in town and many in the state. Folks read both papers because they got different view points of the same event.

By the mid 80s, the newspapers were sending only one set of reporters and by 1986 both papers were purchased by Gannett (thanks to family squabbling—looking at you, Sally Bingham). The Times ceased to publish within a year.

Even when two newspapers are owned by the same company, they can report differently.

Aha. Found it; I was in the wrong thread (all them journalism-y things look alike to me…). This is cross-posted on the ProAdvice thread; the remarks and any responses really belong here.

The (astonishingly) sharp dropoff began when the Berlin Wall fell, and now we consume almost none.

Not something I saw. When I was growing up in Kankakee, we subscribed to the Kankakee Journal (a rag most useful for wrapping the garbage in. Except on the first of April when we could get photos of the submarine races in the K3 River, or of the flying saucer that had landed under the bridge over that river), the Chicago Tribune, and the Chicago SunTime, and the Chicago American. And yes, I read those things–a bane of being the son of high school teachers and having an older brother in college who was interested in the world around him, too. Very little foreign reporting. We read about things going on in Europe, the USSR’s missile secretion into Cuba (even had school assemblies about how to deal with one of the possible outcomes of that), very little about things brewing in Vietnam, very little else. A few years later, when it became en vogue to be against the war in Vietnam, reporting about those doings picked up, from a particular perspective, but very little else unless it was a major event. More, though, what I was getting at with my estimate of disinterest was the relative thing. Yes, there are large numbers of folks here with family ties to their old countries. But they don’t come close to approximating the total population, like they did in times past.

An example, from an indirect perspective, of the disdain journalism itself has for foreign reporting is its universal insistence on referring to terrorists as “militants,” or “insurgents,” or…. These aren’t stupid people using these terms; it’s a clear indication that they don’t care enough about their subject matter even to try to report on it or opine on it with any logical coherence. If the writers don’t care, why should their readers?

I mean, if nothing else, every single American is very affected by events that cause the price of oil to go up and down.

Of course we are. I bought a Ford a couple years ago. It was assembled in America, and virtually every one of its parts, or part components, was imported. But that’s too far a remove for most Americans to see the effects. Certainly we should, but human nature is to not look too far afield. The pack of wolves on the other side of the hill stalking me is less of a threat to me than the lioness who’s confronting me now.

But my argument for reporting from abroad isn’t that we should all be exposed to their amazingly-equal cultures. (Maybe I’m misunderstand your point, though, so let me ask for clarification.)

I was clumsily changing the subject to another aspect of the discussion: the complexity of our modern society (I argue that the complexity is overstated) and that the bottom of it is a too big government whose interest is to increasingly complexify things–obfuscation is power for the obfuscator. Decent journalism–or a more widely read populace–is important to that, but…see below.

Maybe as I share more this week, I can bring you around a bit on why this is such a big part of (what I agree is) the larger problem.

I overstated my case there. I should have said that the modern state of journalism, IMNSHO, isn’t the most important thing here. It is a very important factor; it’s just not alone. But it’s necessary to fix government and to let Business go back to being the dominant root cause. Journalism has a big role to play in that, but We have to do the fixing. Journalism can’t do it for us.

I disagree with you that the operation in Mali was a failure, by the way; albeit our own support of it was…lacking. Our support ranked up there with Obama’s attempt to bill the French (is there a pattern here?) for our airlift and aerial refueling support of operations over Libya (so far as I know, we didn’t try to bill Europe for our ordnance, which they needed after having run out of their own five minutes into the campaign). The French intervention broke the momentum (no small thing in a military operation, where so much depends on morale and self-confidence and personal as well as unit discipline) of the terrorists, and Mali continues to exist as a more or less sovereign and more or less cohesive nation as a result of the French effort. I’ve never been a fan of the French since they quit the heart of NATO over an ego trip, but kudos to them for this.

…a sense of how public judgments about the US are apt to be shaped; France is quite an important ally in many ways….

This might be an interesting discussion in a different thread. Not regarding France in particular, but the concept of how the US is viewed overseas and why–or whether–we should care rather than simply be aware.

…an empirical question, and probably one that would take me a month of (probably) full-time work to answer in a serious way. … But would it be worth it to you to pay a reporter to work on this story, full-time, for a month?

Isn’t this what periodicals do? Pay their reporters for a period of time to develop a story for next week’s or next month’s or next quarter’s edition? Isn’t this what serious dailies do, too–budget their staff to work on such stories while they’re also working on this afternoon’s deadline? Or am I misunderstanding an obsolete model?

Send me to Mali.

You’d probably need somebody to go with you. It’d be a hugely interesting trip for me, too, for a host of reasons. Got the budget?

Eric Hines

Hold on hold on — where did I say that? From everything I can tell, it was an extraordinary success. (When I say “from everything I can tell,” alas, I’m basing this on very limited information — given the lack of reporting.) But it seems to have been the kind of success that’s supposedly impossible — or so we’re always told when someone tries to explain how we’ve screwed up similar operations — so if it’s true, I think it’s highly important to understand how they did it and consider it as a model.

A tiny handful, now. Very few.

Yeah, pretty much. It’s obsolete.

Send me to Mali.

If I had the budget, I’d be there.

You (both) need to take Simon Templar. To be safe, just saying.

Hold on hold on — where did I say that?

From this. Did I misunderstand?

France managed to pull something off that really warrants some thought, given that this is what your tax money was spent on (a failure, clearly).

Apparently we’re on the same page on that, then.

Send me to Mali.

If I had the budget, I’d be there.

So, does that mean I’m invited? Who’s the moneybags around here? Ricochet management, hmm…? You guys listening?

Eric Hines

Well, talk about being careful what you wish for. My brother just called. As I’ve mentioned, his wife’s a UN Peacekeeper. She just got a new assignment.

Bamako.

I’ll let you know what I see after my next family vacation.

Just up the road from Ebola-land….

Eric Hines