Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

The Debate Behind the Debate

The Debate Behind the Debate

The debate over Indiana’s version of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act has already taken some curious twists and turns. The initial response from opponents was to go to the playbook that has been so wildly successful over the past five years: label the law as “hate,” condemn its proponents, and invent wild scenarios that conjure Nazi-esque horrors.

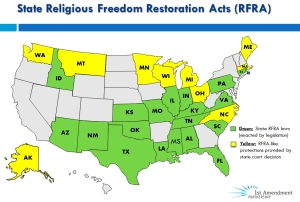

Except something was different this time. The law’s critics — probably overconfident because of their long winning streak — got a little sloppy. Their blanket condemnations were met on this occasion by some defiant, salient points from the other side. Namely, that numerous other states and the federal government have had similar laws for years, and, yet, somehow, those jurisdictions have avoided the descent into Jim-Crow-esque regimes promised as a certainty by opponents.

Except something was different this time. The law’s critics — probably overconfident because of their long winning streak — got a little sloppy. Their blanket condemnations were met on this occasion by some defiant, salient points from the other side. Namely, that numerous other states and the federal government have had similar laws for years, and, yet, somehow, those jurisdictions have avoided the descent into Jim-Crow-esque regimes promised as a certainty by opponents.

Faced with these inconvenient facts, RFRA critics have chosen two paths. One, taken by those like Apple’s Tim Cook, has been to ignore the realities of the application and history of these laws, and simply to continue to drum up opposition. Even politicians are not immune to this phenomenon. Now-Senator Chuck Schumer sponsored the original RFRA bill as a member of Congress, but condemned Indiana’s version this week. Governor Dan Malloy of Connecticut issued a ban on state-funded travel to Indiana over the RFRA, but his own state actually has a RFRA with broader language in some respects than Indiana’s legislation.

The second path has been to distinguish the Indiana law from other RFRAs because of some slightly different procedural points that permit its use as a defense in actions between private parties, rather than simply those where the state is a party. As noted by the Washington Post, this is a somewhat inconsequential distinction. However, critics have to highlight this difference to avoid an embarrassing situation in which many “good” states have this law, and where, for example, people like Barack Obama (as a state legislator) voted for these measures.

The reality is that if someone opposes the Indiana RFRA on the grounds that it might someday allow a court to find a conservative Christian may be able to decline to service a gay wedding, then that opposition should extend to some of the other RFRAs as well.

All these laws do, in fact, is plug a hole created by Employment Division v. Smith, a 1990 Supreme Court case which (briefly) held that laws of general applicability need not receive the highest level of scrutiny used in certain other First Amendment cases. The idea is that a general law that happens to conflict with particular practices of a religion has a lower constitutional hurdle to clear than a law that specifically impacts religious practices.

RFRA was an attempt to elevate such cases to the same strict-scrutiny standard that applies in cases involving direct infringement upon the free exercise of religion. That standard doesn’t mean that the plaintiff always wins, it means that the government must prove that it is advancing a compelling state interest in order to justify its alleged infringement on religious exercise.

A later case, Boerne v. Flores, held that the federal RFRA could not be used in state-level cases. That decision prompted a long list of states to adopt their own versions of the RFRA over the next several years. The laws have been used in a variety of contexts to protect religious objectors who seek to be absolved from following certain laws that clash with their religious beliefs, such as a ban on facial hair in a prison or regulations pertaining to wheeled conveyances that are in conflict with Amish religious and cultural traditions.

The Mother Jones and Gawker crowds would have you believe the RFRA is something close to apocalyptic, but a decade or two of actual experience with these laws strongly suggests otherwise.

So, what’s really going on here?

This is part of a bigger cultural shift—one I’ve discussed in the past.

In a piece about Tim Tebow (remember him?!?) a few years ago, I wrote:

Religion and sexuality gradually swapped places in American culture over the last fifty years in one important respect. We (or some of us) collectively made a decision that sexuality, not religion, could be on display proudly, while religion, not sexuality, was unseemly and needed to stay hidden to prevent upsetting the sensibilities of those it offended.

Religion is now considered by many to be an uncomfortable or inappropriate topic for any public presentation, except in specific, designated places devoid of non-believers. The same progressive thinkers who oppose someone exposing his religion to those who might be offended would be first in line to defend public expression of sexuality that might offend others.

The even larger point that emanates from the above is that sexuality is held as more sacred than religion by an increasingly sizable portion of our population, particularly among younger people.

This is hugely important. If there’s nothing “special” about religious beliefs, then it carries no weight to say that you cannot in good conscience do X because of those beliefs. From a purely secular standpoint, religion cannot be used by someone as a magical way of making other laws not apply to him.

This is why something like RFRA can seem ridiculous to contemporary critics. Conservatives and liberals alike saw merit in such laws a few years ago, when the perception was that everyone from Evangelicals to the Amish to Muslims to Native Americans to atheists would be protected from laws that forced them to engage in activities that conflicted with their religious consciences, so long as the laws were not part of advancing a compelling government interest (for example, a law forbidding murder could never have a religious exemption, because preventing the death of its citizens at the hand of another is the very definition of a compelling state interest).

Now, however, sexuality trumps. If a law allows even the possibility that religious beliefs might lead someone to fail to celebrate someone else’s sexuality, then the laws are deemed “hate.” Sexuality is sacrosanct.

Many on the Right are perplexed by this turn of events. Their position is, “Is it really so terrible that a particular photographer, for example, be allowed not to have to photograph an event that goes against his religious conscience? Particularly when there are other photographers who are willing to provide this service?”

For the Left, the issue is framed as, “A refusal to provide this service is discrimination, and discrimination is bad. End of discussion. You don’t get to discriminate because you can say some magic words that put your beliefs into a special category.”

The gap between these two positions isn’t as far as one might believe. The entire difference in the calculus is the weight given to religious beliefs in a public setting.

One side sees religion as something to be given the utmost reverence, particularly when the force of law is being used in a way that might conflict with it. The other side sees religion as, at best, something that is all fine and good behind closed doors or at a house of worship, but which is otherwise indistinguishable from any other belief system in the context of law or public life. At worst, religion is simply viewed as a cover for discrimination on the basis of something they see as more important—sexuality or sexual identity.

And that’s the debate behind this debate. The debate that we aren’t really having. Yet.

Namely, should religion continue to be something that receives special protection in the law, or should it only receive that protection when it doesn’t conflict with whatever the state holds out as its secular gospel?

Now that the Indiana RFRA discussion has shifted to its second stage, that’s where we’re headed.

There are certainly arguments to be made on both sides. This is a conversation that will take place repeatedly over the next couple of generations. The conversations will move in unexpected directions as the number of Americans who put little stock in the secular value of religious ideas reaches a critical mass.

It does occur to me that — in much the same way that free speech is meaningless if it only includes protection for inoffensive speech — protection for free exercise of religion is meaningless if it only includes “free exercise of religion that does not conflict with the preferences of the government.”

That’s the tension that’s truly at issue. The RFRAs, including this one, strike a pretty nice balance that has worked well for years: The law may force adherents to refrain from acting upon their religious beliefs in certain ways, but only if it has a compelling reason to do so and if the government uses the least-restrictive means to accomplish that goal.

For many people, that isn’t a satisfactory compromise. They require unanimity, compulsory or otherwise.

Should we embrace that version of society, though?

I always use the example of a strident atheist who thinks that circumcision is a barbaric practice based on a 2,000-year-old fairy tale. If that atheist happens to be a caterer, should he be compelled by force of law to cater a bris if asked to do so? Or, should he be permitted to refuse without fear of being sued out of existence? And, if he did refuse, would we say that the law that permitted him to do so was anti-Jewish hate legislation?

It seems to me that the sane thing to do would be to draw a line between discriminating against customers and refusing to participate in an act, event, or message that has a religious or potentially religious component. For instance, if a person who happens to be Jewish asks the atheist caterer to cater a high-school graduation party and he refuses, I’m sympathetic to the idea that this blanket discrimination should be prohibited with the force of law (although a libertarian, which I’m not, might say that even that law should not exist — but that’s a discussion for another day). On the other hand, if he objects to catering a bris, I’m sympathetic to the notion that the atheist should not be compelled by force of law or fear of civil suit to service that event.

As an alternative to all of the above, we could return to where the law was in 1990 and say that laws of general applicability have a lower hurdle to clear. I could actually live with that, as it would at least be a consistent rule. That would mean Muslim prisoners would be forced to shave, no one would be allowed to ingest peyote, the Christian baker would be forced to bake a cake for a gay wedding, and the Sikh would have to surrender his kirpan.

It would also mean that Justice Scalia had it right the first time.

However, if we’re going to agree that religious beliefs still do carry special weight, even in public life, then we need to think about the issue differently. Compelling participation in events or endorsement of ideas in conflict with religious beliefs in the name of tolerance is not tolerance at all.

If we now reject that idea, ok—but we have a lot of repealing to do.

(This piece also published simultaneously at my blog, The Axis of Ego. I’m new here and thought this might be a fair way to “introduce” myself. Forgive the conlaw 101 explanations of the cases referenced below. I’m an attorney, but I write with a general audience in mind when I reference legal concepts and cases. Thanks!)

Published in Domestic Policy, Law

Why is a weight at the end of a rod used to drive something called a hammer or mallet, but a weight at the end of a rod used to actuate a gear called a pendulum?

That depends on what you look like.

What’s interesting about substituting sex for religion is that sex tells us nothing about how to live our lives, except who to have sex with–and even then, it’s not very picky. It doesn’t help us know how to treat other people except in a very narrow way in that one realm, it doesn’t tell us how to form families and raise our children, except that genetic connections are unimportant, it basically gives us no ethical guidance and no information about our purpose on earth, except that it is to have sex in whatever way we think we want to, and not to have opinions (except approving ones) of anybody else’s chosen way of having sex. What could go wrong?

What could go wrong?

Well, not focusing on the sex lives of others might leave us more time to focus on other things.

hey thats called boombatty privilege.

[joke redacted… because patriarchy]

It sure would. That’s why I wish people would not demand that I focus on their sex lives.

That is the reasoning behind the disparate impact theory, aka the everything-is-racist theory.

This shift is something that John Stonestreet at the Colson Center has also commented on.

Food for thought: it may have been cause, it may have been effect . . . but isn’t this elevation of sexual liberty to the ultimate right similar to what occurred in the last days of the Jewish, Greek and Roman empires?

Wonderfully put. This post is well deserving of the mention it got in the Daily Shot.