Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

President Obama has a Brian Williams Problem on Deficits

President Obama has a Brian Williams Problem on Deficits

Despite the recent illogical musings of some liberal economists, including Paul Krugman, deficits and increasing debt are bad things. Not only do they jack up the borrowing costs and necessary amounts of taxation and/or inflation needed to cover the difference, deficits also drain investment capital that could be put to efficient use (and sustainably grow our economy) out of the market and into the hands of notoriously wasteful government bureaucrats.

Despite the recent illogical musings of some liberal economists, including Paul Krugman, deficits and increasing debt are bad things. Not only do they jack up the borrowing costs and necessary amounts of taxation and/or inflation needed to cover the difference, deficits also drain investment capital that could be put to efficient use (and sustainably grow our economy) out of the market and into the hands of notoriously wasteful government bureaucrats.

Deficits are bad. There is no argument. Prior deficit spending by other presidents doesn’t make even bigger deficit spending OK. I wasn’t old enough to vote for George W. Bush either time and, as much as I admire many of the attributes of Ronald Reagan, The Gipper made fiscal mistakes too. I agreed with candidate Obama: trillions of dollars in national debt is unpatriotic. To some degree the president still seems to understand that deficits are a bad thing, even if just politically. At the Democrats’ Winter Meeting this past week, the president (again) took credit for falling deficits, claiming that deficits only seem to go down when Democrats are president. He claimed that our deficits are falling at the fastest rate in 60 years. This is technically true, but that’s the purpose of doublespeak isn’t it?

President Obama needs to learn a lesson from the Brian Williams suspension and stop taking credit for things in which he played absolutely no part. Deficits have fallen, but President Obama has done almost nothing to account for this, except for hiking taxes on people’s health care under Obamacare.

First of all, deficits have fallen from the massive highs resulting from stimulus spending that he himself orchestrated. To credit Obama with falling deficits is like patting a drunk driver on the back for only blowing twice the legal limit when he blew three times the limit before. Bravo! But the car is still wrapped around a tree.

Most of the deficit reduction has come from spending freezes put into place under sequestration. Remember the sequester? President Obama lampooned conservatives at the Democrats’ Winter Meeting for doom and gloom predictions about his economic policies. Yet here’s the president on the sequester:

The pain, though, will be real…many middle-class families will have their lives disrupted in significant ways… hundreds of thousands of Americans who serve their country — Border Patrol agents, FBI agents, civilians who work at the Pentagon — all will suffer significant pay cuts and furloughs…All of this will cause a ripple effect throughout our economy. Layoffs and pay cuts means that people have less money in their pockets, and that means that they have less money to spend at local businesses. That means lower profits. That means fewer hires. The longer these cuts remain in place, the greater the damage to our economy — a slow grind that will intensify with each passing day.

Well, the sequester happened — and two years later the president is bragging about how great the economy appears to be. Underlying data suggests otherwise, but that’s an entirely different topic.

President Obama and Democrats fought tooth and nail against every cent of the sequestration budget cuts, which were technically just reductions in planned future spending. Yet now they want credit for falling deficits?

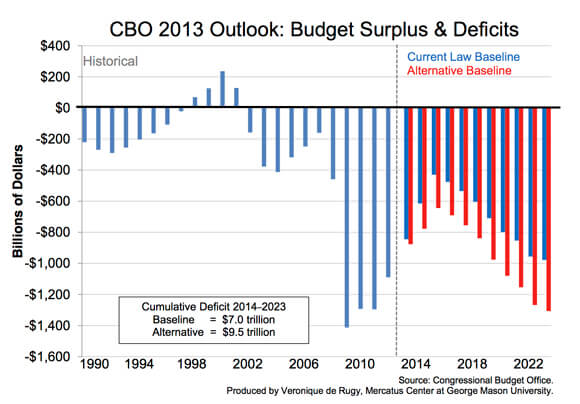

Finally, the president keeps referring to our deficit problem as if it is a thing of the past. While his presidency may be coming to a close, our fiscal nightmare is far from over. By the president’s own predictions, via the White House Office of Management and Budget, the budget never balances. Deficits never go lower than $460 billion (2017) under current projections. We resume trillion dollar deficits within 10 years. Under the president’s plan, the United States government will continue to spend trillions of dollars it does not have in perpetuity, pushing our national debt towards $30 trillion and possibly beyond.

These are the facts: The president was responsible for the massive deficits from which we’ve since come down. The president fought the very policies that have shrunk them. Last, but not least, the president’s own budget projections predict a deteriorating budget situation, with deficits exploding to dangerous levels within 10 years. This is the truth. President Obama is being deceitful. It’s just too bad the country won’t get the same Brian Williams-style six-month suspension from Obama’s reckless fiscal policies.

Published in General

1. Thanks for making the rest of us feel like dinosaurs!

2. Absolutely correct that the sequester was the primary reason the deficits have come down. That and increased revenues (taxes, fees, etc).

3. Meanwhile he has taken the national debt from $10T to an expected $20T by the end of this term. Everything else is bread and circuses.

It’s not illogical at all. You can make the case of particular…levels…of debt and deficits might be problematic after a certain point.

But that doesn’t follow that we are at that point. I.e., not all increases in debt or deficits are bad. It all depends on another variable: primarily…interest rates.

1) Deficits in themselves are meaningless. This isn’t a “liberal” or “conservative” issue. It’s an economic issue. Milton Friedman made the same argument: i.e. you can either pay for stuff through taxes, or through debt. It’s not particularly important which…within a certain constraint of interest rates.

You can argue spending is an issue. But that’s different.

2) Debt is meaningless too. The amount of debt incurred is meaningless, unless it is framed in your ability to repay the debt. 10% of GDP in debt for Zimbabwe might be a terrible thing, if their interests on debt are 20%. 100% of GDP in debt for the US is quite insignificant, if the interest on debt is a fraction of 1% (or, practically, negative interest rate).

3) The level of interest on debt for the US today is less than half what it was, say, 2 decades ago. That’s essentially like a bank telling you that they will lend you money at 0% interest. Is it a good idea to take the bank’s money? Hmm…probably.

4) So simply telling me that we have taken up a lot more debt doesn’t mean anything, if you don’t also tell me that debt is practically free today. So in that sense, taking on more debt is the logical and cost-effective thing to do: it’s cheaper than taxation.

I’d argue that the government would be acting stupidly if it didn’t take advantage of the cheap interest rates to take on more debt.

5) The argument for crowding out is not separate from interest rates. Interest rates are low for precisely the opposite reason: people want safe places to invest their money, which drives interest rates lower for government bonds.

Most of this money is coming from international sources, which negates the “crowding out” argument. It’s people in China saying “investing in China is too risky, and I want safe investments instead”.

So the whole deficit and debt argument is…economically misguided. And this isn’t a “left” or a “right” argument. Milton Friedman made the same argument.

PS: Of course, for political convenience, the argument makes sense if you’re addressing lay people who may not understand it. But in the real world, it actually doesn’t matter…without taking into account interest rates on the debt.

But interest rates on the debt are…pathetically low…which means, you better be taking on more debt (which leads to more deficits)

This may not have been true 20 or 30 years ago, when the interest rate on government debt was much higher. But that’s an important distinction: the underlying assumptions aren’t static.

PPS: This is a similar argument to that made about firms in finance: the optimal level of debt for a firm is…never…zero. There is no argument that “debt is bad”. There’s only an argument about the optimal level of debt.

But how do we know what the optimal level of debt is? Well, that depends on the cost of the debt (i.e. the interest rate you have to promise to pay). That’s basically 0 right now.

So what’s the optimal level of debt then? Some arbitrary number isn’t going to cut it. But you can figure out why that optimal level is higher today than it was when interest rates were higher.

Your entire premise is based in a ZIRP vacuum. The FED will HAVE to raise rates (as soon as this Spring).

And what of UNFUNDED liabilities? Estimates over $100Trillion.

Also, the U.S. is a part of a global debt surge. ECB, Japan, etc. are all following the Feds example of QE. It won’t end well.

None of this makes a difference.

When rates go up, then you issue less debt at that rate.

Unfunded liabilities are a different issue entirely.

In either case, the rates aren’t going to go up by that much. The level of the rate will depend on the amount of demand for US government bonds, which may well increase if things in other economies look less attractive for investors.

In either case, people need to look at debt as an…issuance. You put it on the market, and people buy it. People buy it because they think it’s a safe investment. That’s not likely to change whether rates are close to 0 as they are today, or if they are at 1% or 2%. It’s still dirt cheap from the perspective of the issuer.

So if debt financing is cheap, compared to tax financing, than “deficits” not only make sense, but are the logical thing to do.

I understand that, and you are correct. We are in an economic experiment without precedent. ZIRP is an artificial short term boost to the economy, which has been extended much longer than was originally intended.

It’s clear that the FED is fearful raising rates will slow the economy. Also, I don’t recall anytime in history when there has been so much debt per GDP on a global basis. The pull out of buying treasuries by China or other sovereign nations can have a significant impact.

Natural law also applies to economics: no matter how you tilt a glass, water will always find it’s level.

2-4% rates have been the “normal” for well over a century. One would argue that the rates of the 70s and 80s were the abnormally high rates.

But, of course, there’s a lot of differences between these time periods and today. Primarily: global markets. Demand and access have increased dramatically over the last 2 decades…But this isn’t likely to decrease anytime soon.

Neither did we figure out how to control inflation until the 1980s. So it’s a extraordinary period in that sense too…extraordinary stable inflation rate. I don’t see any reason why this is going to change either.

But the overall point is, that one can’t make blanket statements that “deficits and debt” are a “bad thing”.

I remember interminable lectures by my Democrat brother in law about how Bush was destroying America with his horrible 300 billion dollar deficits.

Since 2008………..crickets.

and

“It’s Bush’s Fault!”

Can you please explain why debt is cheaper than taxation? I understand initial intake of the money might be less costly (cheaper to have people voluntarily buy treasuries vs. the expense of tax collection/enforcement). However, the debt holder’s principal must be repaid along with interest (even if modest), and isn’t that money raised through… taxation? Doesn’t this ultimately require more taxation than a non-debt scenario, since it requires additional taxation to provide the debt holders with an interest payment (even if modest)?

It’s not necessarily the case that you will have to pay…more…taxes to pay back the debt, even at positive interest rates.

There’s opportunity costs associated with paying taxes all at once today, vs. having to spread them out over time. That money could be invested today to (potentially) generate more returns in the future which may outweigh the cost of debt (in fact, it almost certainly will, since the government debt at best will provide you with a hedge against’ inflation, which means, very low returns).

So yes, if the interest rate were zero, we can see why it makes no difference whether we use debt or taxes. But it’s not just no difference…it’s actually better, even at positive rates, because of opportunity costs.

Obviously, that all depends on a lot of other factors, primarily the interest rates and the investment opportunities available, and the overall level of spending.

Now, if you think that the opportunity cost is low, meaning there’s not much you can do with your tax dollars today if you held on to them, and they wouldn’t generate a return for you that will be higher than the interest rate you’ll have to pay in the future, then yes, go with taxes.

But I suspect that’s not the case.

PS: The way I think of it, it’s like buying a house 100% cash, vs, borrowing from a bank. If there was nothing else you could have invested that cash in, to generate a return, then fine, buy it 100% cash. But as long as there was something that you could have invested that money that would have generated a return higher than the interest the bank will charge you…then borrowing is cheaper.

AIG, there are many positive assumptions in your answer and we come at this very differently.

The “debt is cheaper than taxation” approach is easily manipulated to increase spending to unhealthy levels. It also carries the morally dubious burden of shifting the repayment obligation (in the form of taxation) to future generations who had no part in the decision to incur the debt, and who might not even benefit from the borrowing/spending. These factors must be weighed against the opportunity cost of not borrowing at low rates.

You asserted above that “the government would be acting stupidly if it didn’t take advantage of the cheap interest rates to take on more debt.” That might work in the abstract, but reality paints a different picture. When the federal government is in charge of “investing” all that borrowed money, eating the opportunity cost can look pretty attractive by comparison.

1) Rates are determined by future expectations.

2) The government isn’t the one investing anything. The people whose tax money is taken are the ones investing it.

3) Overall levels of spending are important. Yes. But deficits and debt…aren’t the same thing as level of spending.

4) Debt has a build in mechanism for telling you when you’re spending too much. Taxes, are political in nature.