Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

If Washington Isn’t Behind the Decline in US Startups, Then What Is?

If Washington Isn’t Behind the Decline in US Startups, Then What Is?

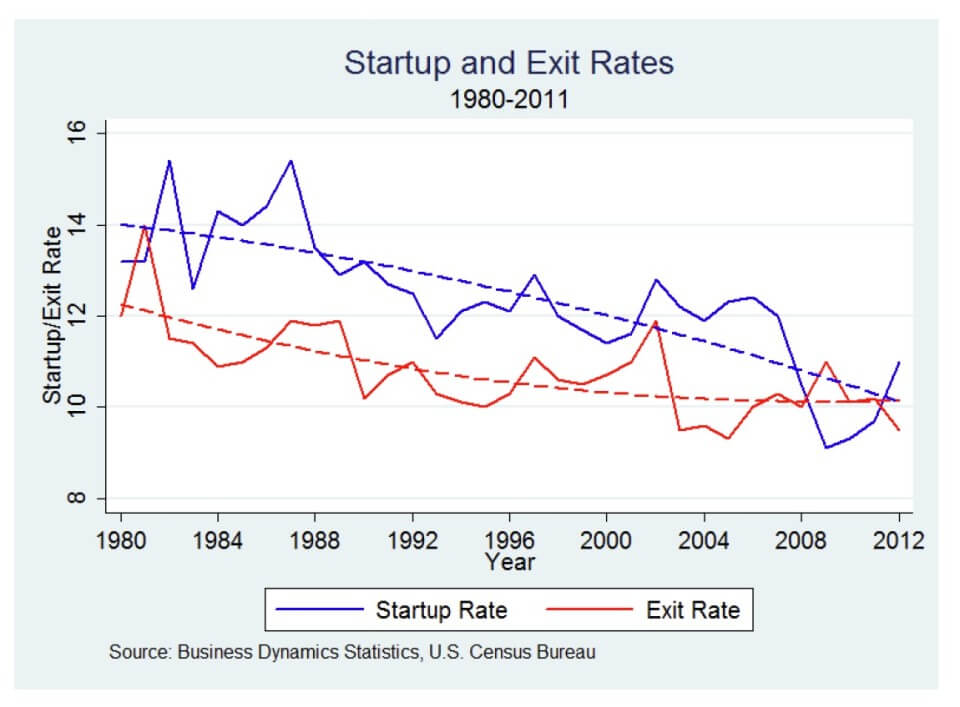

My (seemingly) never-ending mission to figure out what’s going on with the decline in American startup ventures — over the past three decades the annual entry rate of new firms fell approximately from 15% to 10% — continues with research from George Mason University’s Nathan Goldschlag and Alex Tabarrok. They investigate whether federal regulations are to blame. Apparently not:

To investigate the extent to which the decline in entrepreneurship can be attributed to increasing regulation, we utilize a novel data source, RegData, which uses text analysis to measure the extent of regulation by industry. Our analysis suggests that Federal regulation is not a major cause of the decline in US business dynamism. … Contrary to expectation, there is a slight positive relationship; industries with greater regulatory stringency have higher startup rates. We find a similar relationship with job creation rates.

Goldschlag and Tabarrok searched the Code of Federal Regulations for sections with restrictive terms or phrases (“shall,” “must,” “may not”). They then used an algorithm to match language in that section with a particular industry. They also checked whether perhaps more dynamic sectors attracted greater regulation. But “after subjecting the data to a number of different tests we find no statistically significant relationships between dynamism and regulatory stringency.”

So how do Goldschlag and Tabarrok explain the dynamism decline? They offer several possibilities: First, maybe state regulation or legal decisions are having a dampening effect. Second, maybe we are missing all the entrepreneurship happening at older, established firms, especially due to outsourcing: “Apple, for example, is measured in US data as a relatively stable firm but the Apple ecosystem from which Apple sources its product is a maelstrom of entry and exit as Apple hires and fires new firms with each new iteration of the iPhone.” Third, maybe the problem is idea flow, “a slowdown in the technological frontier that reduces the flow of new ideas ready to be profitably implemented.” This is the Great Stagnation scenario. The researchers suggest — in another paper — these policy responses:

The direction of causality is important as the policy levers that we do have may vary in effectiveness depending on the cause. If business dynamism is primary, for example, then we may look for direct levers such as regulation of new businesses (contrary to our preliminary results) or an increase entrepreneurial immigration. If deeper technological change is at work, then our options are more limited, but perhaps policy could be more focused on improving science and math education, investing in knowledge production and fostering creativity.

But if more entrepreneurship is happening at big firms, then the startup decline is less alarming. He cites Alan Mulally’s turnaround of Ford as an example:

Published in GeneralFirst, entrepreneurship is not limited to small firms. Indeed, because of scale, entrepreneurship at large firms is much more important than at small firms. Moreover, there is some evidence that CEOs have become less managerial and more entrepreneurial over time. CEO turnover, for example, has increased over time and the turnover-performance gradient has become more steep; that is, CEOs whose firms perform poorly are increasingly likely to be fired. CEOs are also less likely to be insiders than in the past. In the 1970s only 15% of the CEOs in S&P 500 firms were outside appointments but by 2000-2005 32.7% were outside appointments (Murphy and Zabojnik 2007). The decrease in the appointment of insiders and increase in the appointment of outside, suggests that basic “managerial” knowledge and skills—How does this firm work? What do we do? What relationships need to be managed?—became less important and more general managerial or entrepreneurial ability became more important in managing US corporations.

Allan Mulally’s career is a case in point. He rose not through the ranks of Ford but came to Ford from Boeing where he had been president of Boeing Commercial Airplanes and was credited with a successful competition against Airbus. After retiring from Ford in 2014, he was appointed to Google’s board of directors—further illustrating the importance of general entrepreneurial ability rather than firm specific knowledge. Second, by all accounts Mulally remade Ford into a different firm—not just a different set of products–although there were innovative new designs and building methods–but also a new corporate culture (Hoffman 2013). … We measure new firms as firms which go from zero employment to one or more employed but restructuring and remaking old firms is not counted. If Ford can be said to have been reborn in the ashes of the financial crisis, then innovation, entrepreneurship and reallocation may be larger than we measure. … It’s plausible that information technology has made older and larger firms more flexible, nimble and capable of change.

In the data, do franchises count as “new firms” or are they counted as expansions of the parent company?

Probably mostly washington,

Also I wouldn’t discount the extent that a new pendulum swing to massively centralized services are for anything which requires a capital investment.

Local to regional service IT providers (for instance) are in trouble, especially as their suppliers forward integrate.

States and localities are adding numerous onerous regulations, like the $15 minimum wage, mandatory sick leave, trash disposal regulations (garbage police in Seattle), and other environmental regs. Taxes have gone up on everyone too. How about the Obamacare individual mandate, which disproportionately affects sole proprietors, who are less able than ever to find any kind of group plan?

Im a little confused by this. Entrepreneurship, by definition, is a person who starts, organizes and runs a business usually with high risk and personal investment.

If we start considering large Fortune 100 companies as Entreprenuers (Apple was last entrepreneurial in the early 80’s and Ford was last entreprenuerial in the early 1900’s) then we simple have redefined the word and therefore stats don’t mean anything.

Brookings Inst. showed last year that there are more businesses exiting the economy than there are start ups. THIS is the issue. Apple and Ford are not.

Well, federal regulations are not the only ones, and are probably not the ones that matter most for the average startup business. I suspect that many people without a lot of education and without much capital—including many immigrants—are deterred mainly by state/local regulations from starting the kind of businesses that similarly-situated people would have started a generation or two ago.

Also, there was recently a WSJ article on the reluctance of millenials and younger people to pursue careers in sales….I expect that some of the same psychology makes many of them reluctant to pursue careers in entrepreneurship.

US policy at multiple levels creates a cumulative, structural dampening effect on entrepreneurial activity. This multi-threaded wet blanket is thrown over the entire economy, with relatively stronger sectors determined more by high profit margins and robust intellectual property protection than a lower “shall” count in the Federal Register.

The United States has the highest average corporate tax rate in the world. Given a free market for global capital flows, this means that value–intellectual property royalties, manufacturing margin–must be moved offshore, drying up opportunities for American entrepreneurs. The alternative for the buy American shop is a materially higher tax burden than an optimally organized competitor. The result: inevitable business failure down the road, or a buyout by someone who will pay for the acquisition by reorganizing the business according to prevailing incentives.

The United States regulates by “grandfather effect,” which by definition is fine for existing businesses but a deterrent to anything new. My company operates a semiconductor foundry in Silicon Valley. We inherited the California EPA permits from a firm that shut down as we moved in. If we wish to expand or open a new facility, we face a 2-3 year permitting process. Note that this regulatory paperwork is for a facility that produces no emissions or waste.

The U.S. is also committed to making energy progressively less available and more expensive. The only limit on the president’s commitment to having prices “necessarily skyrocket” is political. Mobile app developers can innovate under such conditions much more effectively than those thinking of producing physical products.

Sarbanes-Oxley and subsequent financial regulations have dramatically reduced the attractiveness of raising capital in US public markets–for companies in all industries. Competitive businesses–i.e. those not focused software or biotechnology–have a very hard time signing up for the world’s highest tax rate, an increasingly inflexible labor market (thank you, Obamacare!), and Kafkaesque regulations.

Consequently, entrepreneurs are increasingly outsourced to foreign countries. California, for example, is becoming something of a theme park for fortunate software moguls, who access a global customer base via the internet while others in foreign lands build the actual devices.

Very little of this has to do with the issue at hand, because that’s what the studies show.

The issues here are several:

1) Entrepreneurship isn’t the same thing as a “start up”. Entrepreneurship goes on…mostly…in established companies. And as it becomes more mature and expensive to carry out, it is carried out inside established companies themselves.

2) The chart is misleading for several reasons:

a) It starts off in 1980, which was the period when a large divestiture wave started in the US economy as conglomerates broke up. In fact, the conglomerate breakup was the result of…regulation change…which made it easier for them to spin off new companies. So the high period of “start-ups” between 1980 and the early 1990s is a function of that wave.

b) the start up rate was relatively flat between the early 90s and 2008. So clearly this has nothing to do with “outsourcing”, EPA, etc etc…since this was also the period when those trends were increasing.

c) Obviously the big decline happened in 2008. That doesn’t need a lot of explanation as to why.

3) So we have 3 distinct periods in this chart. We can’t say the US economy was more “dynamic” in the 1980s because of the higher rate of start ups, if those start ups were simply divisions of established firms which were spun off as separate companies. It was the same companies, under different governance.

Here are some other charts from their study:

High regulatory change vs. low regulatory change…similar trends

There’s no particularly good reason to assume that regulations are a…major… force here.

Technology and governance mode are likely to trump everything else.

AIG, I beg to differ.

I have to disagree with your diagnosis of the source of conglomerate breakup. It wasn’t regulation change but a reduction in taxes and regulations. We see the inverse process at work now. When the political economy is the key business success factor, then bigness is what matters most. You need to have political clout. And when taxation is onerous, then having as large an internal market as possible is helpful in order to shuffle money around and take advantage of the special breaks legislated on account of the firm’s bigness.

Reducing taxes and regulation, as in the 80s, changed the incentives. Economic efficiency became the driving factor, and shareholders could decide how to deploy investment capital, rather than one gihugic conglomerate operating across every business known.

The reverse process is underway today, and has been since George H.W. Bush distanced himself from Reaganomics with his “kinder, gentler [i.e., more liberal] America.”

The conglomerates prior to the 1980s existed not because of internal efficiencies.

They were mostly unrelated conglomerates (hence the term, conglomerate) so they did not benefit from economies of scale or scope. They existed because of anti-trust laws at the time.

Anti-trust laws prevent M&As in the same industry, if this increased the concentration in the industry. So these firms were forced to acquire firms in other industries instead. Once those barriers were removed in the 1980s, they re-structured by divesting the un-related firms.

In fact, they were precisely the opposite of efficient, which is why the market-pressure broke them up. It was more efficient to run the unrelated divisions as separate companies, than under the same corporate governance umbrella.

So it was an increase in market efficiency which caused the break ups of the 1980s.

But this has little to do with taxation. At least, no evidence of that has been shown. Effective corporate taxation in the 1980s actually increased from 1980-1987. And it had been steadily declining since 1950 by that time.

It was, more simply the case of having few opportunities to invest cash in, other than to buy unrelated businesses and create conglomerates through the 1960s and 70s.

In either case, the graph is misleading because it starts off right at the time of a major wave of “new firm creation”, which weren’t new firms actually but spin-offs.

Aging demographics. I think most of the US’s so called economic ills can be traced directly back to that.

AIG, great points. We agree on the economic inefficiency of the conglomerate form of corporate organization. You mention corporate tax rates. I recall seeing data a long ways back pointing to the reduction in personal income tax rates as having the effect of promoting spinouts and other actons tending to return capital to shareholders for redeployment. Was this not also a factor?

Not all regulation is created equal. Some regulation is good, or at least can be managed. If there is environmental and safety regulation consisting of clear prohibitions, that might accomplish some good goals without being so harmful to small business.

But if it’s a kind of regulation that provides opportunity for regulators to meddle, reward friends and punish enemies, or regulation that requires you to schmooz your local regulatory office, that’s an entirely different thing.

I almost wish there were different terms for these two types of regulation, so we could be clear which kind we are talking about.

There might be another factor at play with this reported relationship between regulated industries and startups. The very act of regulation creates new business opportunities. I spent my corporate career working in the environmental and safety areas and starting in the 1970s all sorts of new businesses sparked by these regulations were created.

Now there is still a discussion to be had. Is regulatory induced start up the right use of society resources? Could the money and intellectual energy involved in those start ups be put to better use allowing it in an unplanned manner to meet consumer desires?

The issue of start ups is something separate and distinct from the burden placed on businesses by an enormous and complex web of regulations. I can guarantee you that every business in the U.S., regardless of size, is constantly out of compliance with some regulation.

I don’t know. I’ve never seen any study pointing to taxation as a factor.

And I hope I don’t…because that’s a research idea I want to pursue myself…on dividend taxation ;)

So don’t tell anybody.

PS: Actually I do remember some studies from the late 80s that looked at tax write-offs as a reason for firms to do M&A, i.e. get amortization etc. But not the flip side of divestiture.

The main drive for that, according to the current theory, is the “diversification discount” placed on conglomerates by the stock market. But to be able to un-diversify, they needed changes to anti-trust laws which allowed them to do it.

Either way, my main point was that the 1980-1990 period experienced an unusually high level of “new firm” creation mainly from this wave, whatever cased it.

Re the “un-diversification” argument—there are hundreds of thousands of business startups and closings per year. How could the spinoff of a few entities (maybe 2 or 3 or 4) from a relatively small number of very large enterprises (those big enough to worry about antitrust problems) have a material influence on these statistics?

Hi AIG. Your point (2a) about the chart being misleading is demonstrably wrong. I have raised this point elsewhere, but it bears repeating.

As I understand your argument, you contend that what appear to be a mass of new businesses formed during the 1980’s are really just spin offs from existing conglomerates, not genuine new businesses. So, for example, where there was once one conglomerate with 50,000 employees there are now 5 companies with 10,000 employees each…and 4 of these (the spin offs) look like new businesses in the chart, but really aren’t. Further, the entire surge in new businesses during the 80’s represents situations like this.

We can actually demonstrate that this argument is false.

There is a lovely study by the Census Department indicating that most new job creation comes from newly formed businesses.

https://www.ces.census.gov/docs/bds/bds_paper_CAED_may2008_dec2.pdf

You frequently hear the canard that small business is the engine of job growth. This is not quite accurate. As shown by this Census study, NEW businesses (most of which happen to be small) are the real engine of job creation.

Let’s look at employment numbers from that time period. If your “spin offs” argument is correct we won’t see a surge in employment that accompanies these new businesses. If, however, these are real, genuine new businesses then we will see that employment rose along with these new businesses. That this employment growth was caused by these new businesses.

You can look at either my favorite employment statistic, Employed-Usually Work Full Time (from the Household Survey) or your favorite Total Non-Farm from the Establishment Survey and examine %Change from prior year. In both cases we observe a surge in employment similar in dimension to the surge in new businesses. Conclusion – these are not ‘spin offs’ and are genuine new businesses generating new employment. Your contention that the graph is misleading in incorrect.

In reality, the graph highlights that something important and different was happening in the 1980’s. And the endeavor to explain what that was is a necessary one .

Very interesting discussion. What are the chances, though that this is entirely demographic?

Entries and exits are marginal phenomena that occur as the system seeks some sort of equilibrium. Not all people are suited for business ownership or entrepreneurship, so in any population, there will be a maximum number of potential owners and entrepreneurs. Demographics determine the maximum, demographic changes determine the relative magnitude of the entries and exits. It seems to me that the graphs show net positive increases during the active years of the baby boom and should be expected to show net decreases during the decline of the baby boom.

Hi AF. Interesting idea. I was thinking about something psychological … Appetite for risk taking, something like that. But that could also be age related! Hadn’t thought about that.

This study highlights the fundamental problem of attempting to assign cause and effect to complex systems: Because they are networks of interrelated nodes there are millions of causes and millions of effects, and sorting them out can be impossible.

Economists have responded to this by building simplified models of the economy, but any model runs the risk of simplifying away the things that really matter.

For example, how do we even know what the ‘correct’ rate of startups is? If it’s declined, how do we know if it’s declining away from an optimum, or whether it’s regressing back to the optimum from an artificially high value? The answer is, we don’t. We’re making an assumption that is not supported by any data.

Next, it looks like they used a pretty simple model of regulation – just counting up the ‘shall’ and ‘must’ regulations doesn’t give you any sense of whether those regulations have a disproportionate impact on startups. A regulation for how you must disperse assets when a company is bankrupt probably won’t have much of an effect on new startups, but a regulation that affects the ability to raise capital sure would.

A hypothetical single regulation that said, “A new business must maintain enough capital for two years of operating expenses”, or “A new business can only borrow up to 100% of cash on hand” would probably have a bigger effect on startups than all other regulations combined, but would be counted as one ‘must’. Or more likely, a financial regulation that puts a greater burden on banks for making ‘risky’ investments could easily be a major limiting factor in new startups, but might not even be counted at all because it’s applied to an existing industry not related to the startup.

The cause could be social as well – risk aversion may have increased. Regulations may have biased people towards staying in jobs (for example, locking people into health care plans) rather than starting businesses. The desires of young entrants into the workforce may have changed because entrepreneurship may not be as socially welcomed as it used to be. To know, we’d have to dig a lot deeper into a relatively unrelated dataset, and even then we’d have no way of knowing if it was the cause, an effect, or a correlated effect from another unknown cause.

Would the risk of unknown costs due to Obamacare be counted? I’m guessing the ’employer mandate’ wasn’t counted, as it hasn’t been applied yet. But you have to believe that someone contemplating a startup would be worried about the effect of that regulation.

Then there are government policy choices that aren’t strictly ‘regulation’. For example, an increasing problem for startups in the tech field is the broken patent system which has allowed large corporations to build huge ‘war chests’ of patents which they use to block new entrants into the industry. The root cause is a failure of the government patent office, but it doesn’t show up as a regulation.

Finally, this may simply reflect the maturing of industry in the tech field. When a new innovation or breakthrough creates a new industry, the pattern in the new industry is for a whole lot of entrepreneurial activity as people try to discover how to profit in it, followed by high profits as the paths to profitability are worked out, followed by consolidation as the most successful players grow and begin to displace the weak sisters.

Consider what’s happened to the internet – probably the source of high startup rates in the recent past. Once there were many search engines. Now there’s Google, and I guess Bing. There were many social media sites jockeying for leadership. Now there’s facebook. And so it goes. Maybe if a new industry like space travel or nanotech hits the mainstream we will see a large rise in startups, and the pattern will repeat.

Or maybe it’s all these factors, or interactions between them, or something else entirely. Trying to sort that out is like trying to understand the ‘root causes’ of a sudden decline in the bee population in nature. Often there’s just no way of knowing, but that doesn’t stop ‘experts’ from proclaiming their findings as fact or as solid evidence. Hayek called this ‘scientism’.

Sorry but that doesn’t disprove my argument. New firms that were spun out, doesn’t mean they don’t hire more people.

You’re talking about an unrelated issue: how many they employ, vs. how many new firms there are.

1) They’re not trying to come up with simple models. There’s nothing simple about it.

2) They are trying to come up with a way to measure the impact of regulations. You can disagree with their methods, but that’s just one method they came up with. Others will come up with other methods…and each will have its weaknesses.

3) They’re not making an argument about “optimum”. We don’t know and can’t know what the “optimum” is. They’re just looking at how it impacts the increase or decrease.

4) Of course there’s a lot of interconnections and causes etc. That’s why there’s lots of complicated econometric tools…to account for those as best we can.

Clearly no single study is going to give you a definitive answer, and clearly every study has its drawbacks in terms of how they measured something, what they controlled for, what setting it’s in etc. But that’s why they’re always doing more studies.

The y-axis is the start up vs exit ratio. It’s not an absolute count of new firms being created.

There were comparatively, a lot more divestitures in the 1990s and 2000s than there were in the 1980s.

But, there were also a lot more firms, and a lot more exits. So this is looking at the…ratio….rather than the raw number.

So this bring up a good point: the ratio approach here hides the fact that in terms of volume, there is a LOT more than in the past.

Hi AIG. As per the Census study I referenced they are intimately related. Per that study, most job growth comes from new firms.

That may well be true, but it’s not relevant to the question of new firms created.

Your argument may be an argument of…WHY…we might want new firms to be created at a higher rate, but not as whether or not there’s new firms being created.

Second, and more to Jim’s original question…there’s no reason to assume that the mode of “innovation” or the mode of “creation” is the same in 1980s, the 1990s or the 2000s.

I.e., take the biotech industry as an example. In that industry, you have a symbiotic relationship between big pharma companies, and small “entrepreneurial” companies. But the aim of the small firms is precisely to…cease existing…if successful. Meaning, if their innovation is successful, they get acquired by the big pharam firms so that their innovation can be commercialized.

What may appear as a “bad thing”, i.e. the exit of such small firms, is actually the end goal of those firms.

The same goes for many IT industries: the aim of the small players is to be acquired, and hence “exit”.

Deadly government delays for a small company are readily borne by an established, multi-product enterprise with positive cashflow.

Many many biotech company leaders would be delighted–and indeed labor prodigiously–to become acquirers rather than acquirees. The extremely low success rate at this ambition is more the result of dilatory regulatory timelines and excessive reimbursement hurdles than anything else.

Association is not causality. Most medical companies are acquired because of the enormous capital required to build and maintain a global scale manufacturing and distribution organization, only to have it sit idle and, later, operate well below capacity while working through endless snail-speed audits and approvals from seemingly every governmental body on earth.

The immense dilution required to remain independent through such a regulatory morass–if capital is available at all–often makes selling the only logical decision, particularly when considering remaining risks and more intense competition from a spurned acquirer with unlimited resources.

Amgen made it and Genentech nearly did, but few others can manage it.

Well, there’s no evidence of that. We can only speak of what we have evidence on.

Most biotech companies don’t have the capacity to commercialize their products, so they rely on the established firms which specialize in that.

It’s specialization by firm. At least, that’s what the evidence suggests. And this has been examined in this particular industry since the early 1990s.

Well, that’s the reason they specialize.

Well, there’s no evidence of that either.

That’s just market forces.