Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

If Washington Isn’t Behind the Decline in US Startups, Then What Is?

If Washington Isn’t Behind the Decline in US Startups, Then What Is?

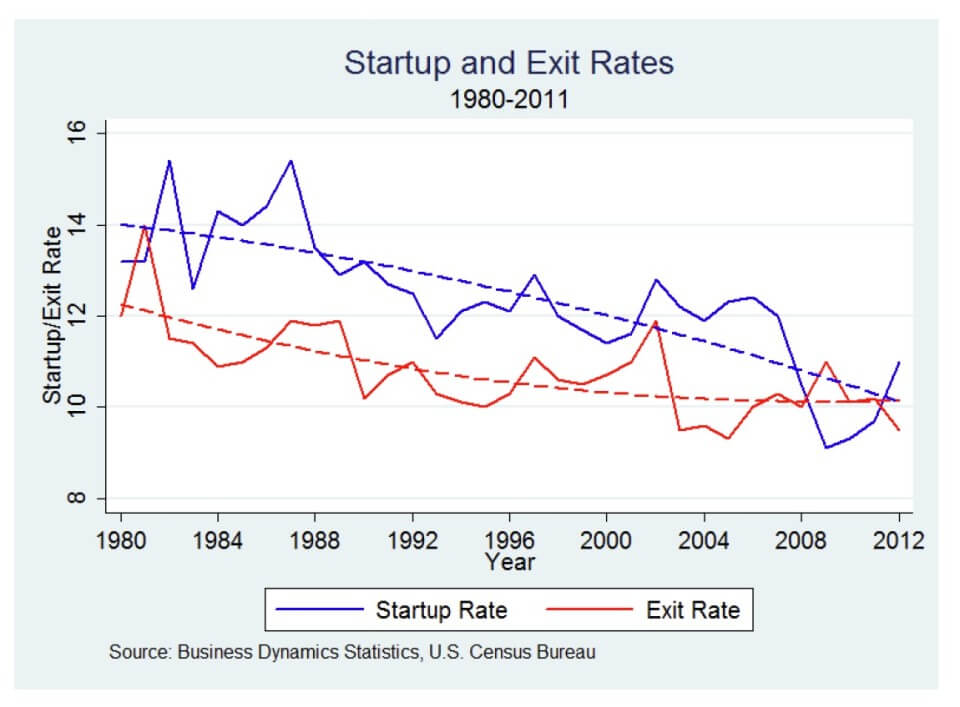

My (seemingly) never-ending mission to figure out what’s going on with the decline in American startup ventures — over the past three decades the annual entry rate of new firms fell approximately from 15% to 10% — continues with research from George Mason University’s Nathan Goldschlag and Alex Tabarrok. They investigate whether federal regulations are to blame. Apparently not:

To investigate the extent to which the decline in entrepreneurship can be attributed to increasing regulation, we utilize a novel data source, RegData, which uses text analysis to measure the extent of regulation by industry. Our analysis suggests that Federal regulation is not a major cause of the decline in US business dynamism. … Contrary to expectation, there is a slight positive relationship; industries with greater regulatory stringency have higher startup rates. We find a similar relationship with job creation rates.

Goldschlag and Tabarrok searched the Code of Federal Regulations for sections with restrictive terms or phrases (“shall,” “must,” “may not”). They then used an algorithm to match language in that section with a particular industry. They also checked whether perhaps more dynamic sectors attracted greater regulation. But “after subjecting the data to a number of different tests we find no statistically significant relationships between dynamism and regulatory stringency.”

So how do Goldschlag and Tabarrok explain the dynamism decline? They offer several possibilities: First, maybe state regulation or legal decisions are having a dampening effect. Second, maybe we are missing all the entrepreneurship happening at older, established firms, especially due to outsourcing: “Apple, for example, is measured in US data as a relatively stable firm but the Apple ecosystem from which Apple sources its product is a maelstrom of entry and exit as Apple hires and fires new firms with each new iteration of the iPhone.” Third, maybe the problem is idea flow, “a slowdown in the technological frontier that reduces the flow of new ideas ready to be profitably implemented.” This is the Great Stagnation scenario. The researchers suggest — in another paper — these policy responses:

The direction of causality is important as the policy levers that we do have may vary in effectiveness depending on the cause. If business dynamism is primary, for example, then we may look for direct levers such as regulation of new businesses (contrary to our preliminary results) or an increase entrepreneurial immigration. If deeper technological change is at work, then our options are more limited, but perhaps policy could be more focused on improving science and math education, investing in knowledge production and fostering creativity.

But if more entrepreneurship is happening at big firms, then the startup decline is less alarming. He cites Alan Mulally’s turnaround of Ford as an example:

Published in GeneralFirst, entrepreneurship is not limited to small firms. Indeed, because of scale, entrepreneurship at large firms is much more important than at small firms. Moreover, there is some evidence that CEOs have become less managerial and more entrepreneurial over time. CEO turnover, for example, has increased over time and the turnover-performance gradient has become more steep; that is, CEOs whose firms perform poorly are increasingly likely to be fired. CEOs are also less likely to be insiders than in the past. In the 1970s only 15% of the CEOs in S&P 500 firms were outside appointments but by 2000-2005 32.7% were outside appointments (Murphy and Zabojnik 2007). The decrease in the appointment of insiders and increase in the appointment of outside, suggests that basic “managerial” knowledge and skills—How does this firm work? What do we do? What relationships need to be managed?—became less important and more general managerial or entrepreneurial ability became more important in managing US corporations.

Allan Mulally’s career is a case in point. He rose not through the ranks of Ford but came to Ford from Boeing where he had been president of Boeing Commercial Airplanes and was credited with a successful competition against Airbus. After retiring from Ford in 2014, he was appointed to Google’s board of directors—further illustrating the importance of general entrepreneurial ability rather than firm specific knowledge. Second, by all accounts Mulally remade Ford into a different firm—not just a different set of products–although there were innovative new designs and building methods–but also a new corporate culture (Hoffman 2013). … We measure new firms as firms which go from zero employment to one or more employed but restructuring and remaking old firms is not counted. If Ford can be said to have been reborn in the ashes of the financial crisis, then innovation, entrepreneurship and reallocation may be larger than we measure. … It’s plausible that information technology has made older and larger firms more flexible, nimble and capable of change.

Hi AIG. ‘Fess up. The thought that anything good might have happened during the Reagan presidency just makes you sick. So what look like and walk like and smell likea spurt of new businesses created in the 80’s just can’t be real.

Certainly in other discussions about this issue you denied these firms created any jobs at all:

“This is why that chart is misleading.”

“All those divested units become…new firms! But they weren’t “new” in any way. Nor did they “create” new jobs. They simply took the existing employees and re-labeled them under a new firm.”

Certainly there are some ‘divested units’ counted among those new firms, but the vast majority of them are real, job creating new businesses. Maybe it was Reagan igniting people’s ‘animal spirtis’. Maybe it was just fortuitous demographics. But they are not the debris of a wave of divestitures.

The y-axis is showing a ratio.

That’s all I got to say about that ;)

PS: What that means is, there could have been 1,000 times more business created in the 90s and 2000s…but the ratio may be lower. It doesn’t speak to…volume.

PPS: Of course this has nothing to do with Reagan or anything political. There’s different corporate governance forms involved over these 3 decades, different types of new firms being created, in different technologies and industries. Each has its own particular features. As an example, I gave the biotech and IT industry…which weren’t really around in the 80s…but which have a very different reason for new-firm creation or exit.

PPPS: And, of course, that’s what the study in question is showing to. Even by industry, the impact of regulations isn’t there. Why? Because there are a lot of much bigger things in the real world than just politics.

“No evidence of that”? Really? I suppose it depends upon your definition. May I suggest that you consider expanding your horizon to consider firsthand experience?

Evidence is not solely scholarly papers, Wall Street Journal articles or Venture Capital for Dummies. In fact, here in Silicon Valley, where I have spent the past 27 years doing nothing but founding, financing and developing technology-based medical companies as both a venture capitalist and entrepreneur, the most important insights on how these things work are regarded as trade secrets. There is no published manual.

Every case is different. Of course.

But, if we’re going to make generalizable statements about even a particular industry, then we have to move outside of anecdotal evidence.

The generalizable evidence on this particular industry is that there is specialization roles between these firms, and a “successful” outcome is one where you end up getting acquired, or your ideas end up getting acquired.

Now you made the statement that the fact that so few of the small biotechs manage to do all this on their own is due to…regulations more than anything else. But that requires evidence. If your personal experiences are generalizable, then we should be able to find general evidence for it.

The same sort of patterns exist in the IT/software industries, and there there are very few regulations. Yet the economies of scale and scope still lead to the same outcomes where “exit” can be the intention in the first place.

One could argue that “regulation” in the biotech industry in fact breeds more new firm creation, since it makes outsourcing of activities to more specialized firms a more economical thing to do, then internalize everything.

Incredible, perhaps delusional, are the words to describe this post and this thread, particularly AIG’s defenses.

As someone working in an industry in which startups have been nearly eliminated by increased regulation, and existing players are regularly being crushed, I find AIG and Pethokoukis’s positions to be so counterfactual as to be hilarious, if they weren’t so misguided.

I suggest that the simple query that the economists used in the root article might perhaps be missing the big picture.

‘Cause it’s surely happening, and I keep hearing it from people in different industries.

In the WSJ, today (and just to tie another thread on Liberty—religious—into this one):

One bank in 5 years. Quite an accomplishment in quashing entrepreneurship. Like many in the financial sector, the fastest-growing department is the compliance department.