Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Time To Dust Off Nuclear Deterrence

Time To Dust Off Nuclear Deterrence

Since the Cold War ended a quarter century ago, we haven’t learned to love the Bomb, but we have stopped worrying about it. As the Obama administration insists on driving the entire Middle East toward nuclear weapons, we had better start worrying about it again. A good place to start may be to dust off the concept of deterrence and re-familiarize ourselves with it.

Since the Cold War ended a quarter century ago, we haven’t learned to love the Bomb, but we have stopped worrying about it. As the Obama administration insists on driving the entire Middle East toward nuclear weapons, we had better start worrying about it again. A good place to start may be to dust off the concept of deterrence and re-familiarize ourselves with it.

What is deterrence?

Deterrence is a strategy of using the threat of military punishment to dissuade an aggressor from attempting to achieve his objectives. A defender deters his opponent by convincing him that any expected gains from his aggression will be outweighed by the punishment he will suffer. A threshold assumption underlying the logic of deterrence is that the aggressor is “rational,” in the sense that his military means are reasonably related to his political goals and he acts based on a comparison of expected gains to potential costs.

If deterrence were easy, there would be no war, since no state would start a war with the certain knowledge that victory is impossible and the costs unbearably high. Unfortunately, the history of war is the history of deterrence failures. Often, one side simply does not have the military means to deter a determined aggressor, as Belgium was unable to deter the German invasions of 1914 and 1940. Such cases are numerous but boring, since the militarily strong will always dominate the manifestly weak if they so choose.

The interesting cases have to do with human failures: miscalculation, misperception, and miscommunication. Sometimes decision makers do not judge a particular deterrent to be credible, for example, if the defender does not demonstrate a clear commitment to defend its interests. As an example, in the early 1980s the UK did not maintain a highly visible military presence in the Falkland Islands. As a result, Argentina’s generals came to doubt Britain’s determination to defend the Falklands from attack.

If a defender’s retaliatory threat is directed at the wrong targets, the aggressor may be less sensitive than anticipated to the costs of aggression, and deterrence may fail. During the Cold War some American strategists worried that the Soviet Union would not be deterred by nuclear weapons targeting its population, and argued that the Soviet leadership should be explicitly targeted instead.

In other cases, deterrence fails because the defender misjudges his adversary’s alternatives and underestimates his need to change the status quo. This is what happened in the 1973 Yom Kippur War, when Egypt attempted to dislodge Israel from the Sinai. In that case, Israeli intelligence failed to appreciate that Egypt’s leadership was willing to strike a blow against a politically unacceptable status quo, even at the cost of suffering defeat on the battlefield. As a result, Egypt’s attack was able to achieve total strategic surprise.

Finally, an attacker may underestimate the cost of punishment or the probability that it will be carried out, based either on poor intelligence or an unclear communication of the threat. Similarly, deterrence may fail if the attacker sees an opportunity for a quick and painless victory, perhaps made possible by a combination of technological and military innovations. In 1940 France had more tanks, planes and men under arms than Germany. But unlike their French counterparts, the German general staff had assimilated the lessons of the military-technical revolution of the 1920s and 30s, understood that the radio, the tank and the airplane had fundamentally changed the nature of military operations, and learned how to combine these technologies with devastating efficiency. Consequently, deterrence failed and France was defeated in less than a month.

What’s so great about nuclear deterrence?

In contrast to conventional forces, nuclear weapons — delivered by modern aircraft or missiles — are excellent deterrents because they make strategic calculations starkly simple. Because of their unambiguous destructive power, nuclear weapons greatly reduce the chances of misperception and miscalculation. An aggressor may believe that the chances that nuclear weapons will be used against him are low; but if he is rational, even this low probability is enough to deter him, given the certain magnitude of the consequences. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, Robert McNamara judged the probability of a ballistic missile launch from Cuba to be one in fifty. Yet he says, “I wasn’t willing to accept that risk. And I know the President wasn’t willing to accept it. And I’m talking about one nuclear bomb on one American city. That’s all.”

Not only are nukes effective at deterring aggression, but their marginal cost is considerably lower than that of conventional defense. Moreover, it is cheaper and technologically simpler to protect nuclear weapons and their delivery systems than it is to develop forces to reliably neutralize them. This fact makes it relatively simple to render a nuclear arsenal virtually invulnerable to attack, thereby attaining a reliable retaliatory capability. Modest protective measures can virtually guarantee that any attempt at preemption would still leave enough weapons intact to threaten the enemy’s cities and population. For any state forced to invest heavily in national defense, these factors make nuclear weapons highly attractive.

Not only are nukes effective at deterring aggression, but their marginal cost is considerably lower than that of conventional defense. Moreover, it is cheaper and technologically simpler to protect nuclear weapons and their delivery systems than it is to develop forces to reliably neutralize them. This fact makes it relatively simple to render a nuclear arsenal virtually invulnerable to attack, thereby attaining a reliable retaliatory capability. Modest protective measures can virtually guarantee that any attempt at preemption would still leave enough weapons intact to threaten the enemy’s cities and population. For any state forced to invest heavily in national defense, these factors make nuclear weapons highly attractive.

The most desirable nuclear relationship, from the standpoint of deterrence, is one where the opposing arsenals are invulnerable to a preemptive first strike and both sides therefore possess a reliable retaliatory capability. If your opponent is firmly convinced that your arsenal is invulnerable, and that no matter what steps he takes, you will always have the reliable means to retaliate, his incentive to initiate a nuclear war diminishes to zero. Mobile land-based missiles mounted on trucks or railroad cars provide the most secure and stable deterrent, because such platforms are extremely difficult to detect and destroy reliably. Submarine-based nuclear missiles are nearly as good, although subs can be hunted down and destroyed if they are not extremely quiet and stealthy. If, however, either side senses that its adversary’s nuclear arsenal is vulnerable to a preemptive strike, then military logic argues strongly in favor of a preemptive first strike.

How has it worked in practice?

In theory, the awesome power of nuclear weapons removes any ambiguity in the minds of policymakers and military strategists. The reality is more nuanced. The 40-year-long standoff between the United States and the Soviet Union left plenty of room for miscalculation, misperception and error. The long shadow of nuclear war encouraged two distinct sets of behavior. On the one hand, nuclear weapons strongly encouraged caution and inhibited adventurism. Once a certain threshold was crossed, however, the nature of nuclear technology and military logic strongly drove both superpowers toward a kind of “guns of August syndrome.” In an acute crisis, with powerful time pressures acting on decision makers, it is possible that military preparations relying on pre-packaged nuclear plans, could have driven political decisions, as on the eve of World War I. Therefore, while the existence of nuclear weapons encouraged general stability in the superpower relationship, it probably contributed to instability in a crisis. We are fortunate to have (mostly) avoided testing the limits of this instability.

It is also useful to keep in mind that, while nuclear weapons are very useful for deterring aggression, they are practically useless for perpetrating it. The Soviet General Staff did put some creative thought into finding ways of using the threat of nuclear war to facilitate the conventional conquest in Europe in the late-1970s and early 80s, but these efforts were highly theoretical and inconclusive. The only successful instance of “nuclear blackmail” occurred, ironically, during 1946 Iran Crisis, when Harry Truman strongly hinted that the U.S. might be willing to use the A-bomb if Soviets did not uphold their promise to withdraw from northern Iran, which they had occupied during World War II. Stalin complied.

But the Iran Crisis was a unique situation. It happened less than a year after Nagasaki — when the U.S. had a nuclear monopoly — and the world was still very uncertain about the meaning of the atomic age. There is no guarantee that nuclear blackmail won’t be attempted in the future, but there is just not much evidence that nukes are good for anything other than deterrence against existential threats.

So what about the Middle East?

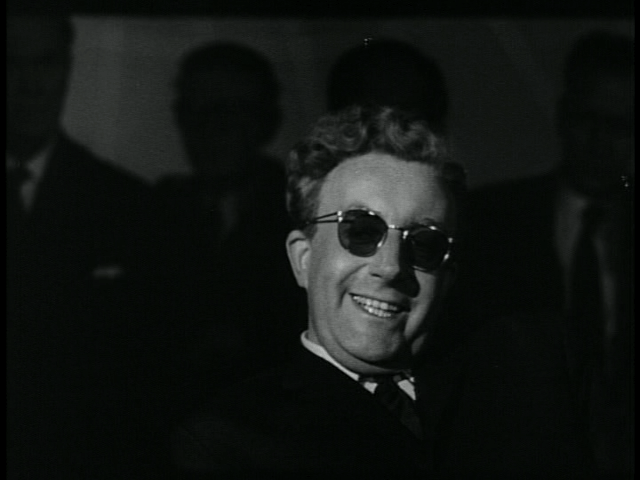

How all of this Strangelovean logic applies to the Middle East is an interesting question. Shakespeare tells us that all the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players. To this Chekhov adds that a gun introduced in the first act must go off in the second or third. Put these two dramatic principles together and consider that, despite Israel’s long-standing pledge “not to be the first to introduce nuclear weapons to the Middle East,” these weapons have in fact been a factor in that region’s conflicts since the mid-1960s.

Where that particular stage is concerned, we are well into the third act.

Image Credits: 1. “Dr. Strangelove” by Directed by Stanley Kubrick, distributed by Columbia Pictures – Dr. Strangelove trailer from 40th Anniversary Special Edition DVD, 2004. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. 2. “Crossroads baker explosion” by U.S. Army Photographic Signal Corps – http://www.dtra.mil/press_resources/photo_library/CS/CS-1.cfm. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Published in General

Here is a thought, with regards to Iran. I often hear that deterrence won’t work because the mullahs are suicidal fanatics, not rational power players like the Soviet Union.

But I don’t think that is completely true. The Iranian leadership consists of human beings who hold power, and that kind of power tends to corrupt ideology. Power is satisfying, and sacrificing one’s life and everything one has control over for radical hatred becomes much less attractive when one holds it. If the threat of nuclear retaliation for a nuclear attack were truly credible, deterrence would still have some force.

That does not mean I think we ought to run the risk.

MAD,again.I am in. Sounds like my first marriage.

MAD will not work for the USA now because the whole world knows that Obama will not use it on them.

#1 Leigh

Accepting, for the sake of argument, what you describe, what seems to me to be a high-probability/high-risk scenario would be internecine conflict between those who have scaled back their ideological fervor for the sake of holding onto power and those who are still Mahdi-seeking apocalyptic true believers (and have their own power-bases and guns).

The top-level prize in such a struggle would be control over the nuclear arsenal (or over the system readied for breakout from potential to actual nuclear-weapons production/possession).

The adjective for Iran’s politico-military echelon (including the mullahs) that seems to be worth bearing in mind is “kaleidoscopic.” So powerful factions with an apocalyptic mindset are ever-present, even if not all-powerful.

For sure, already for quite some time there seems to have been an extraordinary amount of financial corruption among various players inhabiting this echelon. Even so, it’s not a stretch to imagine how lots of fanatical, power-wielding Iranians could and do compartmentalize — Ayatollah Khamenei, for instance, seems to have amassed quite a fortune (mostly seized/confiscated), but his apocalyptic drive seems to have a life of its own in his twisted personality.

So in short, nope — deterrence, containment, and other such approaches have zero long-term success probability, given that those in and/or in strong contention for power do not fit the “rational actor” profile.

In this case does M.A.D. stand for “Mecca’s Assured Destruction”?

Game theory has loads of material on nuclear war. It usually plays out as a Chicken game, with the same strategic dynamics as the James Dean drive-off-the-cliff scene in Rebel Without a Cause. I won’t attempt to babble about all of the game theories that get associated with nuclear war / Chicken. I’m just throwing up a flare to let people know that there is a library of discussion about the strategies of nuclear deterrence.

The most likely benefit of acquiring nuclear weapons is that a nuclear state can’t be invaded. Until now, if a country misbehaves to the point that its enemies have had enough of them, the standard scenario is that the enemies invade and dislodge the regime. But if that regime has nuclear weapons, even if you succeed militarily, the rogue regime has nothing to lose by blowing everything up (including the invading army). Unless you can neutralize the nuclear option ahead of time, no invasion has a chance.

Of course, being immune to invasion is the great equalizer. Who cares if the US has 50 or 100 aircraft carrier groups and a 1000 divisions? If the US can’t use them against you, they’re useless. Conventional war is off the table. Which means, in turn, that a rogue regime isn’t intimidated by a huge American army – and in turn, they’ll feel free to launch asymmetric warfare, because they’re not going to pay any significant penalty.

Not only is it not completely true. It is complete nonsense. They love their power and wealth and want to live as badly as you and me.

#7 Marion Evans

First off, I would suggest you review analyses of the Khomeinist regime published by Reuel Marc Gerecht, at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies. Going by what longtime CIA Operations Directorate veteran and Farsi-fluent Iran specialist Gerecht has to say, your claim of “complete nonsense” is wishful thinking.

Second, just because people might love power and wealth and want to live as badly as we do, that doesn’t dispense with the questions:

1) Under what conditions — what tradeoffs are they unwilling to countenance even if they get to keep power, wealth, and life?

and

2) What combination of (Western/anti-Iranian) deterrence failure (in the Khomeinists’ eyes) plus apocalyptic Shi’a ideological motivation would still push the mullahs to press the button?

Leigh’s phrasing here is a problematic diversion: “suicidal fanatics” is a misreading of the Khomeinists; after all, these Shi’a Persians are very well known for — as the acerbic expression has it — fighting to the last Shi’a Arab for what they believe in.

Re-phrasing the description as “apocalyptic fanatics,” we can see how a desire to immanentize the eschaton would jell very aptly with a love of power, wealth, and life: The Khomeinists would be ushering in a millennial age in which Allah and the returning Mahdi provide them with illustrious rewards, which include power, wealth, and life.

If you have the chance to look at Ari Shavit’s recent book “My Promised Land,” it’s well worth reading at a minimum the chapter (towards the end) on the Iran threat to Israel. In particular, recently-retired IAF general and head of Israel’s Military Intelligence directorate, Amos Yadlin, offers a very sophisticated but bottom-line-centric appreciation of the Iranian regime. Yadlin is (per recent electoral developments in Israel) unquestionably left-of-center, but he is under no illusions. Specifically, he remarks with a strong degree of what can be called “professional admiration” about how the Khomeinists — to use his expression — are playing the long game. Everything is a means to an end in the greater national Iranian effort — which is aimed at hastening the advent of the Mahdi. Accumulation of power and wealth are done for instrumental purposes in the longer term, and a steady war of attrition (using others such as the Hizballahis on the front lines) is an expected and necessary M.O. in this view.

With this in mind, per my #1 and #2 “begged questions” above, we can see that:

1) Power, wealth, and life are enjoyed (and yes, enjoyed far too much by some), but the regime is totally unwilling to countenance a tradeoff whereby they get to keep these things at the expense of solidifying regional hegemony and thereafter using that hegemony as a springboard to bringing in the longed-for golden age; to borrow Obama’s phrasing, the Khomeinists could have taken limitless opportunities to “get right with the world” over the past umpteen years, and yet they haven’t — and they are always explicitly telling us just why this is so.

2) Like the advice Lenin gave regarding the judicious probing with a bayonet of Western intentions and resolve (“If you meet with steel, stop; if you meet with mush, push.”), the Khomeinist M.O. at *minimum* is to keep pushing and probing the limits of adversaries’ will and unity — this pushing/probing is calibrated to greater or lesser intensity to match conditions, but it is ongoing. For example, it may well be that the mullahs pushed their nuclear-weapons efforts deeper into the background at the early stages of the 2003 Iraq invasion, but they wasted no time providing lethal materiel and guidance to Shi’a Iraqi insurgent groups even as their physicists were laying low.

The Khomeinists — a whole array of different true-believer groups within the kaleidoscope of Iranian politico-military life — are convinced that strategic openings to prevailing in epic conflict with the West are sure to manifest themselves in the long term, to their eternal reward. They want to persist in life but only for the purpose of dominating us with death.

Oblo,

OK Oblo if you’ve got the guts to ask the question then I guess I should have the guts to answer or if not at least rephrase it my own way.

The question is whether or not the Iranians themselves are a Religious Doomsday Machine? Once triggered they will behave in a suicidal manner automatically.

Perhaps if they are the Religious Doomsday Machine as the Nuclear Bombs are descending President Obama will assure the world that Iran is not Islamic. No religion would do such a thing.

Obama, the greatest Moot Court advocate ever. Never lost a moot issue.

How wonderfully reassuring.

Regards,

Jim

A missle launched from a tramp steamer, and a nuclear warhead detonated somewhere over the East Coast more or less over Washington DC. Lights out on the eastern seaboard as the EMP fries all the electronics.

Who’s to blame? Do tell. The North Koreans? The Iranians, The Pakistanis? Some “random” group that scratched up the means in secret?

This is only one scenario. I’m looking for the period between November 8, 2016 and January 20, 2017 to be very dangerous as Barack Obama will then be the very lamest of lame ducks.

Phrase it in whatever way you see best, I don’t have anything to argue with in your analysis, even if I had the expertise. I’m not arguing in any way against this understanding of the Iranian regime, and I do not think deterrence is remotely appropriate response to the current crisis. All I am arguing is that their apocalyptic ideology does not completely trump their human nature. They are men, and think and feel as men. The taste of wealth and power tends to corrupt and weaken ideology, and the devastating finality of nuclear war tends to make men question their deepest beliefs. When it came down to the point, someone — some human being — would have to push that nuclear button. And if the Obama foreign legacy should be a nuclear Iran, there may be little choice but to make it unmistakably clear what pushing that button would mean.

The problem with a nuclear Iran is not so much that the Iranian leadership is clearly irrational or that their purpose is clearly to immanetize the eschaton, or whatever. They seem far more rational than our own leadership much of the time, and plenty of smart and sober Israelis and others believe that the Iranians would use their nukes purely for normal deterrence purposes. Lots of others, such as George Friedman, for example, don’t believe that Iran is close to building a bomb, and that they are more interested in having a nuclear program than having nuclear weapons. The problem is that there is enough uncertainty about Iranian intentions that the margin of doubt is politically untenable for Israel. The mullahs are probably rational in the traditional sense, but even a low probability that they really are nuts presents an existential threat for Israel. It would be interesting to know exactly what probability is unacceptable from Israel’s point of view and what Israeli intelligence thinks is the probability that Iran is willing to commit suicide for religious purposes.

It’s because of this uncertainty that the Obama policy towards Iran is very likely to lead to a large regional war. Obama is hellbent on pursuing his rapprochement with Iran, and the Israelis and Gulf Arabs who stand to lose by this can go boil their heads as far as the administration is concerned. Israel can’t destroy Iran’s nuclear program on its own. This will likely drive the Israelis, Saudis and others into an alliance of convenience. No way to know how it will play out but it will be interesting.