Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

A Question About the Book of Exodus

A Question About the Book of Exodus

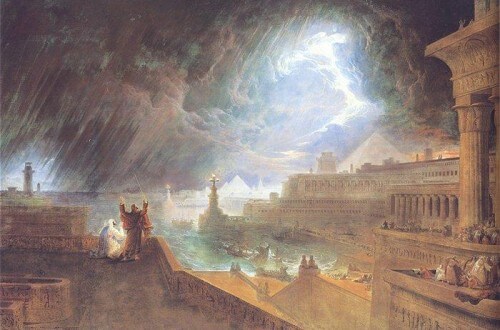

I’m listening to the Book of Exodus and I have a question. Okay, so God pops off these plagues. Then Pharaoh is ready to cry uncle a couple of times, but God hardens Pharaoh’s heart. The part I don’t get is: Why?

I’m listening to the Book of Exodus and I have a question. Okay, so God pops off these plagues. Then Pharaoh is ready to cry uncle a couple of times, but God hardens Pharaoh’s heart. The part I don’t get is: Why?

It seems really counterproductive to the overall plan.

Can anybody shed some light on this for me?

Published in General

Not necessarily. A presumption that he was outclassed is hindsight bias. And even if Pharaoh expected more pain, the damage Egypt had sustained was a one-time sunk cost. In contrast, releasing the slaves — an assets that are productive across many years — would have been a big blow to the Egyptian economy and social order, one which may even have resulted in his own overthrow. (Consider: Was the Confederacy irrational in fighting the Civil War?) From an economic and a political standpoint, not to mention a theological one (Pharaoh may have thought his divinities would ultimately prevail), it may have been completely rational.

I don’t think it’s the mainstream Jewish understanding. The mainstream understanding is that God is omniscient, omnipotent, and benevolent.

Job is a story, not scripture, it was written to explain that bad things can happen to good people, without any reasons. It is not included in the Torah, nor is it included with the histories of the Prophets, who spent most of their time railing against the Israelites for not obeying the law. It’s included with the other stories in the “Writings” such as the Psalms, and the story of Esther, Ruth, Song of Songs, etc. I think Job is also the only story that mentions “Satan” who has no power without G-d’s permission.

Star Trek – Season one, episode 4

A crew member obtains god like powers when the ship goes through a strange force field. He can create and destroy at will. Without moral ethics, he is corrupt. He gives a woman doctor almost as much power so they can be gods together. His jealousy of this companion god has dire consequences. Interesting how this episode ties in with this discussion.

First 3 seasons of the original Star Trek are on Netflix.

On the question of God being too harsh on the Egyptians, it helps to step back and look at some systematic theology that is spread throughout scripture.

It it is hard for us to fully understand the extent of God’s holiness and the depth of our own sinfulness. See Isaiah’s vision of God in Isaiah chapter 6. He enters the presence of God and it is terrifying.

Isaiah 6:5

And I said:” Woe is me! For I am lost; for I am a man of unclean lips, and I dwell in the midst of a people of unclean lips; for my eyes have seen the King, the Lord of hosts!”

Our sin deserves a death sentence as God said in the garden. That punishment was postponed by God’s mercy. We are given the chance to repent, but we have earned his punishment. There are times when God pours out his wrath on sinful men. Those who escape his wrath do so by His mercy.

Other examples of this include the flood. Humanity was destroyed except for a remnant.

Canaan was cursed and his descendants land was given to Israel.

Kay of MT said:

“Job is a story, not scripture, it was written to explain that bad things can happen to good people, without any reasons. It is not included in the Torah, nor is it included with the histories of the Prophets, who spent most of their time railing against the Israelites for not obeying the law. It’s included with the other stories in the “Writings” such as the Psalms, and the story of Esther, Ruth, Song of Songs, etc. …”

Are the Writings not Scripture ? Are they second-class scriptures? I thought they were included in the Tanakh ?

Speaking of things that some Jews do not consider scripture, I was reading Matthew today, and thought you might appreciate this quote from chapter 13:

Enjoying all of this *immensely*! Thanks, once again, Fred.

A lot of good ideas above.

I think the Bible contains this “heart-hardening” concept in other places:

Psalm 81:12

“So I gave them over to their stubborn hearts to follow their own devices.”

Romans 1:28

“Furthermore, just as they did not think it worthwhile to retain the knowledge of God, so God gave them over to a depraved mind, so that they do what ought not to be done.”

This leads me to believe that God “hardening Pharaoh’s heart”, as it is written in Jacobean English, is a judgment against Pharaoh, not a tactic to achieve Hebrew liberty. After refusing to repent, God eventually punishes men by handing them over to the evil that controls them.

God’s motives/actions are rarely clearly explained in the Bible. On this text I think we’re all just making educated guesses on God’s motive in hardening Pharaoh’s heart.

Iyov/Job is most definitely “scripture” in that is one of the 24 canonized books (using the word “book” loosely) that comprise the Tanach (or Tanakh).

The “ch” or “kh” part of Tanach/Tanakh is the elided Hebrew for “Ketuvim” or “Writings,” comprising those books Kay mentions (Daniel, Psalms, Chronicles, 5 Scrolls, etc.).

The canonization, finalizing Tanach, was deliberated on and decreed by the “Men of the Great Assembly” during early Second Temple times.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Assembly

The Talmud Bavli (Babylonian Talmud), Daf (folio pp.) 14b-15a has the authoritative summary of the canonization decisions, along with discussions identifying (with varying degrees of certainty) authors of the various non-Torah (non-Pentateuch) books among the 24.

One thing that SoS, at least one other person on this thread, and I have have tried to indicate is that use of the *earliest* (rabbinical) commentators — such as Rashi, Ramban (Nachmanides), etc. — is key in comprehending at least one level (in some cases more than one level) of what the Torah is saying.

(Granted, typically it is also necessary for us moderns to have *further* exegetical help from more-recently-published “guides” to the words of these commentators themselves.)

At least, this is the traditional Jewish perspective — it certainly holds true in the study and comprehension of the “Oral Torah,” i.e., the Oral Law (and lore) tradition that orthodox Jews consider inseparable from the Written Torah (i.e., given at Sinai at the same time), and which itself was set down in written form in the Mishna and Gemara (i.e., the Talmud).

This perspective holds that the farther back in time the rabbinic authority/scholar consulted, the closer to the most accurate transmission of the original tradition/text and its intent (i.e., its meaning for moral instruction and the reasons for the words employed in conveying that instruction).

Substantially at odds with the modern, secular ethos.

Consulting early medieval Jewish commentators adds insight, but I was not trying to suggest that doing so is necessary. I would never discourage anyone from trying to engage with the text directly. Although Judaism insists on an authoritative interpretation for legal decisionmaking (i.e., the Oral Torah), there is a long tradition of giving wide latitude for individual interpretation of the narrative and moral lessons.

A clarification or two:

1: The Five Books are considered by Jews to be the most important of all the books of the Torah because they are considered the direct words of G-d, unfiltered through prophets. So there is most surely a hierarchy in Judaism.

2: I claim that G-d is not omniscient because the text does not make any other claims. Indeed, it shows that G-d often changes His mind, in reaction to what mankind chooses to do. But I agree with SoS that the mainstream Jewish view is otherwise. Nevertheless, I would claim that this view is in error, and heavily influenced by Greek and Christian theology over millenia.

Canaan was a separate point from the flood. He was cursed after the flood. His descendants were subject to God’s wrath when he sent Israel into their land.

However you view the scope of the flood, the reason is clear. God killed men for their wickedness. Your view brings up an even bigger mystery, though. Why didn’t God send Noah on a long walk?

SoS — my apologies for erroneously citing you.

So with that understood and apologized for, can I say then that we part ways over the necessity of use of the exegetes/commentators?

I think it’s only theoretically true that one can engage with the (Hebrew) Torah text directly.

(Noting, for example, the Yeshivat Har Etzion editors of the new “Torah MiEtzion” series of exegeses suggestion in their Foreword to the Bereishit/Genesis volume that there needs to be, and can be, a move away from “Chumash [Pentateuch] with Rashi” to just “Chumash,” i.e., engaged directly.)

(http://www.korenpub.com/EN/categories/maggid/Har_etzion)

Ultimately, IMO, a reader of the 5 Books of Moses is at minimum trying to discern Pshat.

(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peshat)

Surely that is what Fred here is trying to obtain via his question — at least that is probably *one* of the things he’s seeking.

And just as surely, whether we’re explicitly aware of it or not, that’s what most of us are trying to provide Fred with — we can throw in the homiletical (Drash) if and as we like, but that has to stand with the Pshat.

(comment continues)

(comment continuation from above)

For better or worse, there are multiple definitions of Pshat, or at least so it appears.

(The above Wikipedia entry gives some flavor of this; no doubt you’ve been exposed to many definitions and/or approaches to “learning Pshat” in your own Torah studies.)

The particular definition of Pshat I’ve found most workable is one that I think Rabbi Menachem Leibtag (of Yeshivat Har Etzion and other Jewish learning institutions in Israel) put forward:

Pshat is the plain meaning of a given passage of Torah text, in broad majority (Jewish) view with authoritative basis/backing — as that plain meaning would have been understood by reasonably knowledgeable *average-Joe* Jews from the time of that text’s composition (dictation by God to Moses at Sinai) up through at least the destruction of the First Temple.

Emphasis on “reasonably knowledgeable average-Joe Jews” — after the First Destruction, that knowledge/understanding of the Pshat of the Torah text would be preserved and transmitted/disseminated by the rabbis.

And like it or not, that ends up taking one back to reliance on exegetes/commentators such as Rashi, who stand in direct line in that tradition transmission.

Danny, I disagree. The Torah is true on all levels – both in the text itself, and through thousands of years of layers of gloss.

The problem is that most people do not read the text carefully enough to see what it is telling us. And they try to read it as a descriptive document instead of as what it is: a prescriptive document, explaining what G-d wants from mankind.

When my book comes out, I’ll hawk it here so that I can be sure to welcome your critical review!

iWc — I never said anything remotely like the Torah not being true on all levels (Ch”v).

I said that engagement with the Torah text is first (and should be first) an engagement with the Pshat level.

(Anyone reading this comment, please refer to a Wikipedia entry I link to in my above prior comment, explaining the concept/level of “Pshat” in the Torah/5 Books of Moses text.)

I also said that Fred’s question was on the level of Pshat — and that while some of us on the thread were answering him on the homiletical level (which in Hebrew-language Torah exegesis is called “Drash”), we first off have to make sure that we’re providing Fred with credible Pshat-level responses.

There’s a plethora of homilies (“Drash”-level interpretations) out there, but Pshat comes to tell us, in plain-meaning-of-the-text form (per my Rabbi Leibtag definition above), why a given passage of Torah text is as it is, where it is.

And further I said that that Pshat tradition of “uncovering”/”unpacking” the plain meaning of the text stretches backwards and forwards through Rashi.

Rashi enables your “prescriptive” reading by elucidating the “descriptive.”

iwC — Further to my comment/reply above, see for example this great (and dense!) examination of Parashat Bo.

Everyone else here on the thread, don’t be afraid to click on this and give reading it a try too!

Particularly as it focuses on the part of Sefer Shmot (Book of Exodus) where we’re wending our way through the latter progression of the Ten Plagues (“Makkot” in Hebrew) up to the final Plague, Makkat HaBechorot (The Plague of the Firstborn).

http://www.vbm-torah.org/pesach/bo-56.htm

iWC — As you can see from this article, it’s something like 80-plus-percent (90-plus-percent?) Pshat, and the Drash elements are very intimately bound up with the Pshat anyway.

The “descriptive” in the Pshat of the Torah narrative text that Rabbi Leibtag discusses in this article — in other words, “descriptive” Pshat as transmitted to and by Rashi in the chain of rabbinic tradition — contains its own “prescriptive,” in effect.

A reasonably knowledgeable average Jew, standing in the First Temple precincts and listening to the King reading these passages aloud from the Torah, would have understood both their descriptive meaning and prescriptive import per what Rashi illuminates as Pshat.

That is a really good question that has caused some controversey. Did God eliminate the Pharoah’s free will by “hardening his heart?” I think that’s a different question, but to me that’s the more profound question.

I’ve never liked this definition. Instead, I prefer the approach of Rabbi Brovender: The p’shat is the contextual meaning (which may not be “plain” at all), while d’rash is the extracontextual or hidden meaning and is usually derived by reference to other textual sources.

Interpretations of contextual meaning are not uniform, so there are different takes on p’shat.

D’rash is not necessarily homiletical; it is a method of approaching the text. Jewish law is mostly derived through d’rash, because it treats the Torah as a timeless, unified whole. (Consider the passage cited at the end of the morning blessings: “Rabbi Ishmael says: The Torah is niDReSHet through 13 principles….”)

The two approaches are vastly different — d’rash subordinates both chronology and context (though “no Torah text is ever fully divorced from its p’shat” [BT Shabbat]) — but I see them in a kind of Venn diagram, in which some text cannot be understood contextually without resort to other sources. Rashi thus often cites midrash to explain difficult p’shat.

(cont.)

(cont.)

To bring the discussion down a little ;-) I’ll make an analogy to the Star Wars movies. They should stand on their own, and it’s not illegitimate to interpret them in ways that contradict the “expanded universe” of books etc. But if you want to understand the importance of Biggs, or understand what a womp rat is, you’ll need to look to cut scenes or novelizations to fill in the gaps.

SoS — Not to take away from Rabbi Brovender’s definition of Pshat, but it doesn’t take away from the definition from Rabbi Leibtag that I tried to convey above — my sense, at any rate, is that the Brovender definition is subsumed under the Leibtag one.

That Leibtag definition has to be seen in its fullness (copy/paste from above):

Pshat is the plain meaning of a given passage of Torah text, in broad majority (Jewish) view with authoritative basis/backing — as that plain meaning would have been understood by reasonably knowledgeable *average-Joe* Jews from the time of that text’s composition (dictation by God to Moses at Sinai) up through at least the destruction of the First Temple.

In any case, again, what I say is that (as I perceive it) Fred has been *requesting* Pshat, but frequently the responses coming back on this thread are essentially Drash.

I like your definition of Drash very much, and in its way (so far as I perceive it, at least), your definition dovetails (or lends support) to what iWc was saying just above.

What Fred could benefit from is Rabbi Yitzchak Etshalom’s (http://www.etshalom.com/) volume on Exodus.

Morning Fred,

Starting with the idea that God has heard his people moan under bondage and that He will lead them to their own land, God intends a clean and permanent break with Egypt and all it represents. After 400 years it is difficult for the Jews to leave all the old behaviors, they even miss the pots of meat that they had in Egypt and wished that they had died there. The path from bondage to the beacon of God will have several steps. There can’t be a path where the Pharaoh sees the light, that would mean that the Jews would not leave, or if they did it would be clouded. That God creates the world and illuminates Himself to man through people he chooses (Moses and the Pharaoh) leaves many questions. Would the Pharaoh have converted and believed in God if God had not hardened the Pharaoh’s heart, or is God trying to make the Pharaoh’s stubbornness more comprehensible to us, or is God showing that He can control all things including our hearts. Although we do not know why, we know that the goal is to free us from bondage.

SoS — On further reflection (if I can call it that), I do want to take slight issue with a point you raise about Drash.

(Incidentally, for others on the thread, this Wikipedia entry kinda-sorta illuminates the distinctions and interrelationships involving the major Torah exegetical “categories,” including Pshat and Drash.)

(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pardes_(Jewish_exegesis))

Regarding Rashi and his occasional resort to Drash and citation of midrash (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Midrash) for Pshat “unpacking” purposes:

As you (SoS) no doubt know, Rashi usually relies on the Midrash Tanchuma when he feels compelled to use midrash to get at the Pshat of a given passage.

Tanchuma is non-legal (aggadic) midrash.

I feel it necessary to state this “obvious” (to SoS) point because of your allusion to the use of Drash in *legal* (halachic) interpretation of Torah text.

(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rabbi_Ishmael)

We get back here to the “descriptive” versus “prescriptive” divide per iWc.

Legal (halachic) Drash is used for Torah law derivation since at its core it takes precisely this “prescriptive” tack — one which, yes, as an attribute looks at Torah text as as timeless whole.

Homiletics exists as a subclass here.

Spoiler alert!

Yes, I in no way meant to suggest that d’rash is an approach used only for legal interpretation. Rather, I think it’s a distinct approach to the text, sometimes but not exclusively employed for homiletics — an approach which is only rarely warranted when looking for the p’shat. I was responding to your propositions that (a) understanding the “true” meaning of the text requires study of early and medieval Jewish commentators, and (b) that d’rash is best understood as homiletics. I’m guessing that my attempts to keep my response brief led to the misunderstanding. I’m concerned that we have hijacked this thread. Perhaps it would be better to continue this conversation in a new one.

SoS — Agreed and understood on all points.

And certainly no intention of hijacking the thread.

Only intention was to point out that — as best as I could discern — Fred was asking for illumination in a form that boils down to Pshat, and that instead of providing responses in Pshat form, many on the thread (their very good intentions notwithstanding) were, unawares, providing Fred with responses in Drash form (essentially).

As a general matter, personally, I am always uncomfortable with (however unintentionally) shortchanging people who seek and deserve an understanding of the Torah text in its Pshat form — not least because that was the form in which the “average-Joe Jews” among our forefathers at Sinai received the text from God via Moses, and thereby elected to become God’s servants with Moses and thus live in an eternal covenantal bond as a distinct people.

Rav Kook had said that nowadays traditional orthodoxy has to work hard to present itself in the most intellectually responsible and rigorous manner it can, because young Jews seek and indeed require such or else they will turn away.

I see Fred as inquiring in a similar manner.

Hence my harping on providing him the Pshat.

Fred–Have the Calvinists weighed in yet? This is actually the text that led me to Calvinism–a rejection of free will and an embrace in a God who exercises sovereignty over man. In the end, God hardened Pharaoh’s heart to magnify His own glory. Any other answer is pure speculation.

See Romans 9.