Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Again, the 1980s Boom Was About More Than Just the Reagan Tax Cuts

Again, the 1980s Boom Was About More Than Just the Reagan Tax Cuts

Until I started reading the new issue of the Economist magazine, I was unaware that a new Ronald Reagan biography — “Reagan: The Life” by H.W. Brands — would soon hit the market. (“Mr Brands recounts Reagan’s triumphs and the scandals even-handedly, and concludes that the Gipper’s achievements were comparable to those of Franklin D. Roosevelt, the president who led America most of the way towards winning the second world war.”)

But maybe I telepathically sensed the book’s impending arrival and that explains why I have been blogging so much lately about the Gipper. Or, more likely, I have felt compelled to throw a penalty flag on the improper use of Reaganomics by some current GOP presidential candidates. I don’t have a whole lot to add to what I’ve written previously, except to tie up a few loose ends on issues suggested by readers.

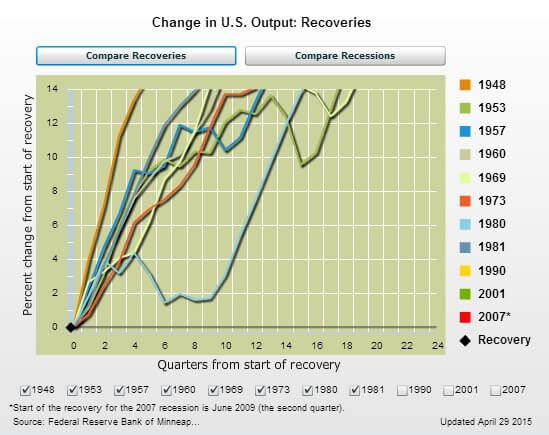

One contentious issue is to what extent the Reagan tax cuts contributed to the strength of the 1980s recovery. Some readers seem to think that only the Reagan tax cuts played a role. They were surprised by economists disagreeing. First, one has to acknowledge that V-shaped recoveries were the rule of the postwar era through the 1980s, as seen in this chart:

The only recovery that stands out is the 1980 downturn, and that’s because the 1981-82 recession followed so quickly. So I think it is weird when calculating the strength of the 1980s boom to count the immediate recovery years but not include the recession that itself played a role in the recovery’s strength.

Then there’s the role of monetary policy. A recent Brookings literature review noted that Martin Feldstein and Doug Elmendorf found in a 1989 analysis “that the 1981 tax cuts had virtually no net impact on economic growth. They find that the strength of the recovery over the 1980s could be ascribed to monetary policy. In particular, they find no evidence that the tax cuts in 1981 stimulated labor supply.”

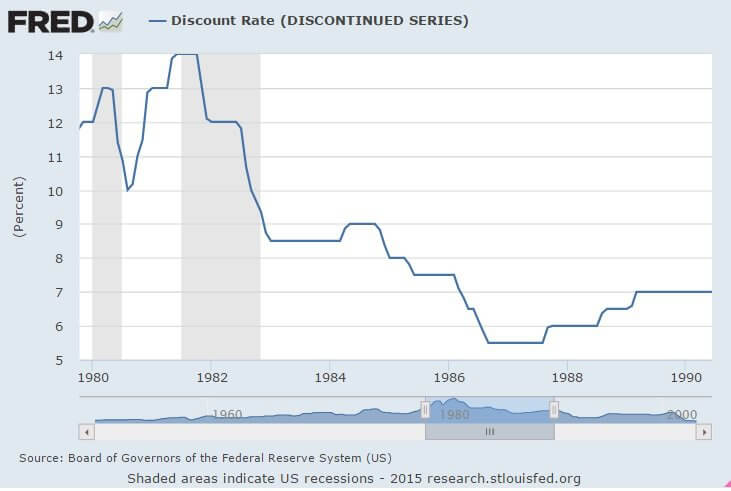

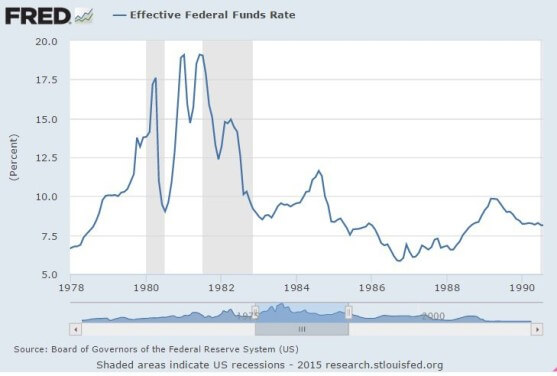

I would only say that it hardly seems a stretch to say that monetary policy played an important role in the fast recovery just as it did in the deep recession itself. Just look at these two charts, one of the discount rate and the the other of the federal funds rate:

Wow, looks like some serious monetary easing to me. From a 1994 NBER analysis by economist Michael Mussa:

By the end of June [1982], the very slow growth of M1 for five months had erased the January bulge and brought this aggregate near to the upper limit of its 1982 target range. M2 continued to grow along the upper limit of its range. At this point, adherence to the monetary targets would have implied continuation of a tight monetary policy to bring both M1 and M2 toward the midpoints of their announced ranges. Some members of the FOMC (Governor Wallich and Reserve Bank Presidents Black and Ford) clearly favored this course. Alternatively, in view of the depressed level of business activity, the FOMC could have explicitly raised the targets for monetary growth. Governor Teeters, long a proponent of a somewhat less tight monetary policy, was an advocate of this latter option. The FOMC pursued neither of these courses. It did, however, raise the short-term growth targets for M1 and M2 by 2 and 1 percentage points, respectively, and it instructed the manager of the Open Market Desk that “somewhat more rapid growth would be acceptable.” With this decision, the FOMC effectively began fundamental change in the course of monetary policy in the direction of substantially greater ease.

Initially, this change in policy was not apparent in the behavior of the monetary aggregates, as M1 declined slightly in July, while M2 growth increased modestly. In the face of a still deepening recession, however, the Federal funds rate dropped from 14.5 percent at the end of June to 15 percent by mid-July and to 11 percent by the end of July. The Federal Reserve Board cut the discount rate half a percentage point, to 11.5 percent on 19 July, by another half percentage point on 30 July, and by another half percentage point on 13 August. By late July, financial markets began to take the hint. The yield on three-month Treasury bills fell more than 4 percentage points between late July and the end of August, while longer-term bond yields declined more than 1.5 percentage points. Stock prices began what was to become the great bull market of the 1980s with a strong rally in August.

The Federal funds rate fell to 10 percent by 18 August and to 9 percent just before the FOMC meeting on 24 August, at which time the tolerance range was reduced to 7-1 1 percent. Monetary growth picked up considerably in August, with M1 and M2 rising at rates of 12 and 13 percent, respectively, and quite rapid monetary growthgenerally continued to the end of 1982 and throughout 1983. The Federal funds rate fell to 9 percent by the end of 1982 and generally ran in the range of 8.5-9.5 percent during 1983. The discount rate was cut five more times between 17 August and 17 December, down to a level of 8.5 percent, where it was held throughout 1983.

Thus, the very tight monetary policy that the Federal Reserve embarked on in November 1980 began to be reversed in July-August 1982-a year after the officially recognized starting date of the 1981-82 recession. Economic activity continued to decline until November 1982, with the unemployment rate rising ultimately to a peak of 10.8 percent. The demon of inflation, however, had finally been tamed. During the twelve months of 1982, the CPI rose only 3.8 percent, and the annual inflation rate would remain generally in the neighborhood of 4 percent through the rest of the decade.

Now, none of this is to say the Reagan tax cuts were ineffectual or irrelevant or failed. Far from it, In fact, I think they were pretty darn important, a point I have repeatedly made. And Reagan also deserves credit for supporting the Volcker Fed during the downturn. Tax cuts matter (a lot), but they aren’t the only thing that matters.

Published in Economics

Didn’t Reagan at least partially undermine his own tax cuts when he signed TEFRA into law?

One of the things I got out of reading Econoclasts was that supply-side economics isn’t just lowering marginal income tax rates but also requires a stable currency. If the object of the exercise is increased capital formation, this makes perfect sense. If the currency is inflating madly, the additional capital is going to get sucked pdq into real (and really unproductive) assets. The continued (bipartisan) popularity of weak dollar arguments suggest that none of us ever really got this point. Larry Kudlow excepted of course.

Someday could you explain what Martin Feldstein meant by “stimulating the labor supply?” Sounds like it’s something oversexed plutocrats do on pleasant spring days with their servants as a beer river on their estate runs over their grandmother’s paisley shawl. That just can’t be what an economist means by it.

[edit] I think I get it. He means the increased propensity to work caused by the lowered marginal rate. Was that ever really the main goal or something you have to say because you think capital formation is a tough sell politically?

The case economists usually make for why the Reagan tax cuts mattered usually goes something like this: by cutting taxes and increasing defense spending, Reagan blew up the federal deficit. This caused the dollar to rise, and the resulting overvaluation caused inflation to fall. That is what allowed the Fed to loosen monetary policy (this is sometimes referred to as Reagan’s “fiscal twist”).

Personally, I think the tax cuts did improve incentives, but they did so in the 90s, not the 80s. It can take a long time for that sort of change in incentive to propagate throughout the economy.

It depends what you mean by “weak currency.” It’s impossible to devalue in real terms without increases net national savings, which is why a lot of us are for a weak dollar and cuts in fiscal expenditure. This is basically what the GOP has done since 2010, and I would argue that it’s been very effective, given the circumstances we faced.

Also, I don’t understand why “stable dollar” advocates don’t complain about dollar instability on the upside. Having one’s currency overvalued by 50% will also suck capital into unproductive assets, for example residential real estate.

John Tamny, in his new book Popular Economics, argues that an important reason for the economy’s good performance during the 1980s and 1990s was the strength of the dollar. A strong dollar is consistent with the falling interest rates your charts show. Tamny also argues that at least part of the flight of capital into housing during the George W. Bush years was the Bush administration’s policy of weakening the dollar. A falling dollar, while theoretically boosting exports, makes investment risky. Businesses are reluctant to invest dollars today when the dollars they can expect to earn tomorrow will be worth less. Instead, capital finds refuge in real estate and commodities – that is, in things that retain value. He supports his argument by pointing out that the housing crash was worldwide. When the United States weakened its currency, other nations followed suit, sparking their own real estate booms.

The housing bubble was caused by weak a currency? All evidence says otherwise. Our current account deficit reached 6 of GDP in the mid 2000s, for crying out loud.