Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

More A-bombs, and the Immoral Presidency (?)

More A-bombs, and the Immoral Presidency (?)

Warning: Very long post ahead.

As in Peter’s case, Fr. Miscamble’s (intriguing) posts have prompted some reflection on Truman’s decision here. For most of my life, I was of the opinion that Truman absolutely did the right and moral thing, for the reasons that Fr. Miscamble has explained and several Ricochet readers have argued. In the end, the dropping of the bombs surely saved many more lives—those of American and Japanese soldiers, but also of Japanese civilians—than they claimed. In the past few years, influenced by my theology-student brother and some reading on the bombings, I’ve walked back from that position, and am now in a “still puzzling through it” mode.

One conclusion I have reached, though, is that it seems wrong to lump the a-bombs in with the conventional bombing raids of German and Japanese cities that took place earlier in the war—even though the cumulative effects of those bombings may have, over time, killed more people. These weapons are apples and oranges. Little Boy and Fat Man could not be limited to specific targets; they could not be intended only for, say, dams in the Ruhr industrial region or a particular Mitsubishi aircraft factory. To use them at all was to knowingly obliterate an entire city, and thus to intentionally target innocents—something of a different nature than regrettably accepting the possibility of “collateral damage” that might or might not materialize when attacking a non-civilian target.

Moreover, the sheer amount of destruction, human misery, and, yes, death unleashed by those weapons was qualitatively different from the effects of the conventional weapons used throughout the war. Regular bombing raids didn’t vaporize scores of thousands of men, women, and children in less than an instant; they didn’t produce the same kinds of agonizing injuries and deaths, for which “horrifying” is an understatement. They didn’t unleash radiation that shot through the cells of people who otherwise appeared to have escaped the bombings unharmed, only to begin days later vomiting up the lining of their internal organs, bleeding through every orifice until they were corpses with no blood left. They didn’t contaminate toddlers who would die of cancer before reaching their teen years. I think it is impossible for us to wrap our minds around the terror that must have been experienced by people who in one instant were preparing breakfast in their kitchens and in the next climbed out from beneath the rubble into a layer of hell Dante never explored. The sheer scope of what these weapons vaporized, flattened, burned, and irradiated—and the shock that such devastation would have delivered to every human sense and feeling—defies, I think, imagination.

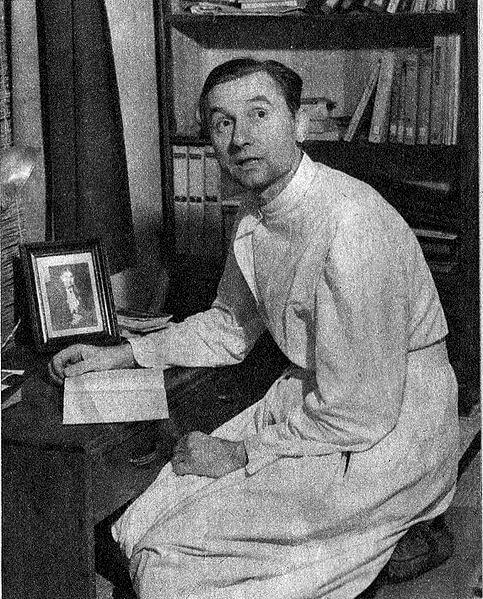

For personal reasons, I have found that the evil in what happened on August 6 and 9, 1945, is clearest when juxtaposed against innocence and holiness: episodes where the bombs collided with the Catholic Church. To that end, I would recommend to anyone interested in the topic of the bombs—Catholic or not—John Hersey’s Hiroshima. Originally published in The New Yorker—the magazine devoted its entire August 31, 1946, issue to the essay—it tells the story of the bombing through the eyes of six survivors. One was a German Catholic priest, living in a Jesuit community not far from the hypocenter. The compound was destroyed; some of the priests were badly injured; they escaped the fires closing in on them and struck out in search of help from a nearby Novitiate. A passage from Hersey:

The morning, again, was hot. Father Kleinsorge went to fetch water for the wounded in a bottle and a teapot he had borrowed. He had heard that it was possible to get fresh tap water outside Asano Park. Going through the rock gardens, he had to climb over and crawl under the trunks of fallen pine trees; he found he was weak. There were many dead in the gardens. At a beautiful moon bridge, he passed a naked, living woman who seemed to have been burned from head to toe and was red all over. Near the entrance of the park, an Army doctor was working, but the only medicine he had was iodine, which he painted over cuts, bruises, slimy burns, everything—and by now everything that he painted had pus on it. Outside the gate of the park, Father Kleinsorge found a faucet that still worked—part of the plumbing of a vanished house—and he filled his vessels and returned. When he had given the wounded the water, he made a second trip. This time, the woman by the bridge was dead. On his way back with the water, he got lost on a detour around a fallen tree, and as he looked for his way through the woods, he heard a voice ask from the underbrush, “Have you anything to drink?” He saw a uniform. Thinking there was just one soldier, he approached with the water. When he had penetrated the bushes, he saw there were about twenty men, and they were all in exactly the same nightmarish state: their faces were wholly burned, their eyesockets were hollow, and the fluid from their melted eyes had run down their cheeks. (They must have had their faces upturned when the bomb went off; perhaps they were anti-aircraft personnel.) Their mouths were mere swollen, pus-covered wounds, which they could not bear to stretch enough to admit the spout of the teapot. So Father Kleinsorge got a large piece of grass and drew out the stem so as to make a straw, and gave them all water to drink that way. One of them said, “I can’t see anything.” Father Kleinsorge answered, as cheerfully as he could, “There’s a doctor at the entrance to the park. He’s busy now, but he’ll come and fix your eyes, I hope.”

Since that day, Father Kleinsorge has thought back to how queasy he had once been at the sight of pain, how someone else’s cut finger used to make him turn faint. Yet there in the park he was so benumbed that immediately after leaving this horrible sight he stopped on a path by one of the pools and discussed with a lightly wounded man whether it would be safe to eat the fat, two-foot carp that floated dead on the surface of the water. They decided, after some consideration, that it would be unwise.

Father Kleinsorge filled the containers a third time and went back to the riverbank. There, amid the dead and dying, he saw a young woman with a needle and thread mending her kimono, which had been slightly torn. Father Kleinsorge joshed her. “My, but you’re a dandy!” he said. She laughed.

He felt tired and lay down. He began to talk with two engaging children whose acquaintance he had made the afternoon before. He learned that their name was Kataoka; the girl was thirteen, the boy five. The girl had been just about to set out for a barbershop when the bomb fell. As the family started for Asano Park, their mother decided to turn back for some food and extra clothing; they became separated from her in the crowd of fleeing people, and they had not seen her since. Occasionally they stopped suddenly in their perfectly cheerful playing and began crying for their mother.

It was difficult for all the children in the park to sustain the sense of tragedy. Toshio Nakamura got quite excited when he saw his friend Seichi Sato riding up the river in a boat with his family, and he ran to the bank and waved and shouted, “Sato! Sato!”

The boy turned his head and shouted, “Who’s that?”

“Nakamura.”

“Hello, Toshio!”

“Are you all safe?”

“Yes. What about you?”

“Yes, we are all right. My sisters are vomiting, but I’m fine.”

Father Kleinsorge began to be thirsty in the dreadful heat, and he did not feel strong enough to go for water again. A little before noon, he saw a Japanese woman handing something out. Soon she came to him and said in a kindly voice, “These are tea leaves. Chew them, young man, and you won’t feel thirsty.” The woman’s gentleness made Father Kleinsorge suddenly want to cry. For weeks, he had been feeling oppressed by the hatred of foreigners that the Japanese seemed increasingly to show, and he had been uneasy even with his Japanese friends. This stranger’s gesture made him a little hysterical.

Around noon, the priests arrived from the Novitiate with the handcart [to transport priests too severely wounded to walk]. They had been to the site of the mission house in the city and had retrieved some suitcases that had been stored in the air-raid shelter and had also picked up the remains of melted holy vessels in the ashes of the chapel.

In Nagasaki, the juxtaposition is more poignant. The Nagasaki area, readers may know, is where Christianity came to Japan in the 1500s. For a time, foreign missionaries were allowed to evangelize, though the Tokugawa shogunate eventually began persecuting Catholics. In 1597, 26 were crucified in Nagasaki (the martyrs were canonized in 1862). In the years that followed, the shogunate implemented fumi-e—the term refers to both the policy and the object around which it centered—requiring Japanese to trample images of Christ or the Virgin Mary. Those who hesitated were identified as Christians; if they refused to turn from their faith, they were executed in Nagasaki. After Japan reopened itself to foreigners in the 19th century, Bernard Petitjean, a French priest who eventually became bishop of Nagasaki, oversaw construction of the Oura Catholic Church in the city; after its foundation was laid, he was approached by Japanese Christians who revealed that, without priests or chapels, they and their forebears had managed in secret to keep their faith alive for more than 200 years.

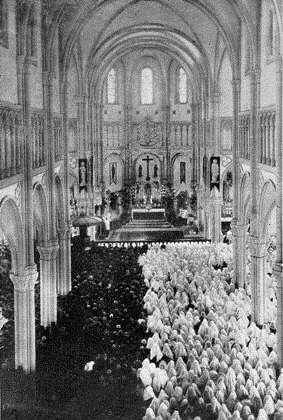

It is against this backdrop that one must consider the history of the Urakami Cathedral. Completed in 1914 after 30 years of construction, the cathedral was the largest in the Far East; it was also the centerpiece of Urakami’s Catholic district, the heart of Catholicism in Nagasaki and Japan.

It is against this backdrop that one must consider the history of the Urakami Cathedral. Completed in 1914 after 30 years of construction, the cathedral was the largest in the Far East; it was also the centerpiece of Urakami’s Catholic district, the heart of Catholicism in Nagasaki and Japan.

Around 11 am on August 9, 1945, the cathedral was filled with priests and worshippers in spiritual preparation for the August 15th feast of the Assumption of Mary, to whom the cathedral was dedicated and to whom the Urakami Catholics had a special devotion. By that time, Bock’s Car pilot Charles Sweeney had given up on his primary target, the military factories of Kokura, because they were hidden by smoke from a nearby bombing; Nagasaki, the secondary target, was mostly hidden by cloud cover. A cruel twist of fate and an opening in the clouds meant that Urakami, not downtown Nagasaki, was hit: Urakami Cathedral was practically Ground Zero. All those inside were killed, and thousands of Christians in Urakami were destroyed along with them, surpassing in one instant the toll of Nagasaki Catholics killed in centuries of persecution.

Cathedral before and after

In October 1945, a Trappist monk, Fr. Kaemon Noguchi—originally from Urakami—visited the ruins of the cathedral before returning to his monastery in Hokkaido. He began digging around the debris in search of some artifact from his church that he could bring with him. He came across a remnant of a beloved painted wood statue of the Virgin that had been brought from Italy in the 1930s; all that had survived the bombing was her head.

The “Madonna of Nagasaki” is now on display in the rebuilt Urakami Cathedral, erected on the site of the destroyed church. When it was brought to New York last year, Archbishop Dolan said:

The “Madonna of Nagasaki” is now on display in the rebuilt Urakami Cathedral, erected on the site of the destroyed church. When it was brought to New York last year, Archbishop Dolan said:

And it is this head that is haunting: she is scarred, singed badly, and her crystal eyes were melted by the hellish blast. So, all that remains are two empty, blackened sockets.

I’ve knelt before many images of the Mother of Jesus before: our Mother of Perpetual Help, the Pieta, the Virgin of Guadalupe, Our Lady of Lourdes, just to name a few.

But I’ve never experienced the dread and revulsion I did when the archbishop showed us the head of Our Lady of Nagasaki …

Again, it was not possible to drop Fat Man and Little Boy without intentionally incurring these results. I ask myself, If I were president of the United States, could I knowingly incinerate the faithful at Mass or priests hearing confessions? Could I vaporize or melt down chapels and chalices and tabernacles and icons? And knowing that such acts would be multiplied and multiplied again, killing thousands upon thousands of innocents, could I intentionally bring about such destruction in a matter of seconds? No matter how much it would benefit my country? I don’t think I could.

But then again, I’m not president—nor would I want to be. If I read Fr. Miscamble’s post correctly, his conclusion is that while the decision to drop the bombs was not moral, it was simply required of Truman by virtue of the office he held. And I think I may be at the same place: that it was immoral of Truman to order the bombing, but that it was the right thing to do—or at least justifiable—as an act of presidential leadership. He has blood on his hands, but the job he held sometimes requires the immoral staining of one’s hands with blood. (That’s why it’s a job I wouldn’t want.)

For the record, I’m not a pacifist. (Indeed, far from it.) I’m not anti-nuclear; in fact, I think Japan’s move away from nuclear power in the aftermath of Fukushima is economic suicide (but that’s another post). Nor am I anti-American and, again, I’m not convinced that using the a-bombs was the wrong thing for America to do in the context of a hideously brutal war. But I wonder if sometimes those of us who resist the traditional hostility to the use of the bombs don’t go too far in defending the morality of the decision, failing to distinguish what would have been prudent (and justifiable in the name of prudence) from what was morally right.

This applies to the present day as well. Decisions that make perfect sense as a matter of tactics, or grand strategy, or self-defense, or national interest are sometimes whitewashed as moral acts. The result is that, in order to defend, say, a particularly unpalatable act of war, we contort ourselves into all kinds of strange justifications that do a disservice to both our perception of morality and our appreciation of what war—and wartime leadership—really requires.

So I’m curious to know what others think of this divide: between what is demanded by presidential leadership and by other forms of responsibility for a nation’s safety and well-being, and what is strictly moral, especially in times of war. Some, I gather, will think that no responsibility can truly demand immorality. I’m not convinced of that—yet.

Thanks to readers for putting up with the long (and meandering) post, and thanks to Fr. Miscamble for opening and contributing to this discussion. I look forward to reading his book soon, now that it’s no longer $80 on Amazon.

Published in General