Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

More A-bombs, and the Immoral Presidency (?)

More A-bombs, and the Immoral Presidency (?)

Warning: Very long post ahead.

As in Peter’s case, Fr. Miscamble’s (intriguing) posts have prompted some reflection on Truman’s decision here. For most of my life, I was of the opinion that Truman absolutely did the right and moral thing, for the reasons that Fr. Miscamble has explained and several Ricochet readers have argued. In the end, the dropping of the bombs surely saved many more lives—those of American and Japanese soldiers, but also of Japanese civilians—than they claimed. In the past few years, influenced by my theology-student brother and some reading on the bombings, I’ve walked back from that position, and am now in a “still puzzling through it” mode.

One conclusion I have reached, though, is that it seems wrong to lump the a-bombs in with the conventional bombing raids of German and Japanese cities that took place earlier in the war—even though the cumulative effects of those bombings may have, over time, killed more people. These weapons are apples and oranges. Little Boy and Fat Man could not be limited to specific targets; they could not be intended only for, say, dams in the Ruhr industrial region or a particular Mitsubishi aircraft factory. To use them at all was to knowingly obliterate an entire city, and thus to intentionally target innocents—something of a different nature than regrettably accepting the possibility of “collateral damage” that might or might not materialize when attacking a non-civilian target.

Moreover, the sheer amount of destruction, human misery, and, yes, death unleashed by those weapons was qualitatively different from the effects of the conventional weapons used throughout the war. Regular bombing raids didn’t vaporize scores of thousands of men, women, and children in less than an instant; they didn’t produce the same kinds of agonizing injuries and deaths, for which “horrifying” is an understatement. They didn’t unleash radiation that shot through the cells of people who otherwise appeared to have escaped the bombings unharmed, only to begin days later vomiting up the lining of their internal organs, bleeding through every orifice until they were corpses with no blood left. They didn’t contaminate toddlers who would die of cancer before reaching their teen years. I think it is impossible for us to wrap our minds around the terror that must have been experienced by people who in one instant were preparing breakfast in their kitchens and in the next climbed out from beneath the rubble into a layer of hell Dante never explored. The sheer scope of what these weapons vaporized, flattened, burned, and irradiated—and the shock that such devastation would have delivered to every human sense and feeling—defies, I think, imagination.

For personal reasons, I have found that the evil in what happened on August 6 and 9, 1945, is clearest when juxtaposed against innocence and holiness: episodes where the bombs collided with the Catholic Church. To that end, I would recommend to anyone interested in the topic of the bombs—Catholic or not—John Hersey’s Hiroshima. Originally published in The New Yorker—the magazine devoted its entire August 31, 1946, issue to the essay—it tells the story of the bombing through the eyes of six survivors. One was a German Catholic priest, living in a Jesuit community not far from the hypocenter. The compound was destroyed; some of the priests were badly injured; they escaped the fires closing in on them and struck out in search of help from a nearby Novitiate. A passage from Hersey:

The morning, again, was hot. Father Kleinsorge went to fetch water for the wounded in a bottle and a teapot he had borrowed. He had heard that it was possible to get fresh tap water outside Asano Park. Going through the rock gardens, he had to climb over and crawl under the trunks of fallen pine trees; he found he was weak. There were many dead in the gardens. At a beautiful moon bridge, he passed a naked, living woman who seemed to have been burned from head to toe and was red all over. Near the entrance of the park, an Army doctor was working, but the only medicine he had was iodine, which he painted over cuts, bruises, slimy burns, everything—and by now everything that he painted had pus on it. Outside the gate of the park, Father Kleinsorge found a faucet that still worked—part of the plumbing of a vanished house—and he filled his vessels and returned. When he had given the wounded the water, he made a second trip. This time, the woman by the bridge was dead. On his way back with the water, he got lost on a detour around a fallen tree, and as he looked for his way through the woods, he heard a voice ask from the underbrush, “Have you anything to drink?” He saw a uniform. Thinking there was just one soldier, he approached with the water. When he had penetrated the bushes, he saw there were about twenty men, and they were all in exactly the same nightmarish state: their faces were wholly burned, their eyesockets were hollow, and the fluid from their melted eyes had run down their cheeks. (They must have had their faces upturned when the bomb went off; perhaps they were anti-aircraft personnel.) Their mouths were mere swollen, pus-covered wounds, which they could not bear to stretch enough to admit the spout of the teapot. So Father Kleinsorge got a large piece of grass and drew out the stem so as to make a straw, and gave them all water to drink that way. One of them said, “I can’t see anything.” Father Kleinsorge answered, as cheerfully as he could, “There’s a doctor at the entrance to the park. He’s busy now, but he’ll come and fix your eyes, I hope.”

Since that day, Father Kleinsorge has thought back to how queasy he had once been at the sight of pain, how someone else’s cut finger used to make him turn faint. Yet there in the park he was so benumbed that immediately after leaving this horrible sight he stopped on a path by one of the pools and discussed with a lightly wounded man whether it would be safe to eat the fat, two-foot carp that floated dead on the surface of the water. They decided, after some consideration, that it would be unwise.

Father Kleinsorge filled the containers a third time and went back to the riverbank. There, amid the dead and dying, he saw a young woman with a needle and thread mending her kimono, which had been slightly torn. Father Kleinsorge joshed her. “My, but you’re a dandy!” he said. She laughed.

He felt tired and lay down. He began to talk with two engaging children whose acquaintance he had made the afternoon before. He learned that their name was Kataoka; the girl was thirteen, the boy five. The girl had been just about to set out for a barbershop when the bomb fell. As the family started for Asano Park, their mother decided to turn back for some food and extra clothing; they became separated from her in the crowd of fleeing people, and they had not seen her since. Occasionally they stopped suddenly in their perfectly cheerful playing and began crying for their mother.

It was difficult for all the children in the park to sustain the sense of tragedy. Toshio Nakamura got quite excited when he saw his friend Seichi Sato riding up the river in a boat with his family, and he ran to the bank and waved and shouted, “Sato! Sato!”

The boy turned his head and shouted, “Who’s that?”

“Nakamura.”

“Hello, Toshio!”

“Are you all safe?”

“Yes. What about you?”

“Yes, we are all right. My sisters are vomiting, but I’m fine.”

Father Kleinsorge began to be thirsty in the dreadful heat, and he did not feel strong enough to go for water again. A little before noon, he saw a Japanese woman handing something out. Soon she came to him and said in a kindly voice, “These are tea leaves. Chew them, young man, and you won’t feel thirsty.” The woman’s gentleness made Father Kleinsorge suddenly want to cry. For weeks, he had been feeling oppressed by the hatred of foreigners that the Japanese seemed increasingly to show, and he had been uneasy even with his Japanese friends. This stranger’s gesture made him a little hysterical.

Around noon, the priests arrived from the Novitiate with the handcart [to transport priests too severely wounded to walk]. They had been to the site of the mission house in the city and had retrieved some suitcases that had been stored in the air-raid shelter and had also picked up the remains of melted holy vessels in the ashes of the chapel.

In Nagasaki, the juxtaposition is more poignant. The Nagasaki area, readers may know, is where Christianity came to Japan in the 1500s. For a time, foreign missionaries were allowed to evangelize, though the Tokugawa shogunate eventually began persecuting Catholics. In 1597, 26 were crucified in Nagasaki (the martyrs were canonized in 1862). In the years that followed, the shogunate implemented fumi-e—the term refers to both the policy and the object around which it centered—requiring Japanese to trample images of Christ or the Virgin Mary. Those who hesitated were identified as Christians; if they refused to turn from their faith, they were executed in Nagasaki. After Japan reopened itself to foreigners in the 19th century, Bernard Petitjean, a French priest who eventually became bishop of Nagasaki, oversaw construction of the Oura Catholic Church in the city; after its foundation was laid, he was approached by Japanese Christians who revealed that, without priests or chapels, they and their forebears had managed in secret to keep their faith alive for more than 200 years.

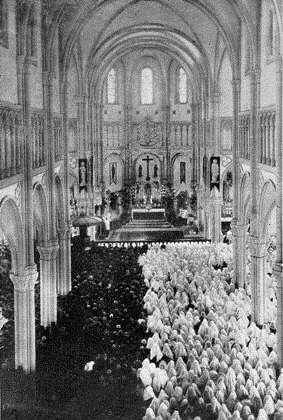

It is against this backdrop that one must consider the history of the Urakami Cathedral. Completed in 1914 after 30 years of construction, the cathedral was the largest in the Far East; it was also the centerpiece of Urakami’s Catholic district, the heart of Catholicism in Nagasaki and Japan.

It is against this backdrop that one must consider the history of the Urakami Cathedral. Completed in 1914 after 30 years of construction, the cathedral was the largest in the Far East; it was also the centerpiece of Urakami’s Catholic district, the heart of Catholicism in Nagasaki and Japan.

Around 11 am on August 9, 1945, the cathedral was filled with priests and worshippers in spiritual preparation for the August 15th feast of the Assumption of Mary, to whom the cathedral was dedicated and to whom the Urakami Catholics had a special devotion. By that time, Bock’s Car pilot Charles Sweeney had given up on his primary target, the military factories of Kokura, because they were hidden by smoke from a nearby bombing; Nagasaki, the secondary target, was mostly hidden by cloud cover. A cruel twist of fate and an opening in the clouds meant that Urakami, not downtown Nagasaki, was hit: Urakami Cathedral was practically Ground Zero. All those inside were killed, and thousands of Christians in Urakami were destroyed along with them, surpassing in one instant the toll of Nagasaki Catholics killed in centuries of persecution.

Cathedral before and after

In October 1945, a Trappist monk, Fr. Kaemon Noguchi—originally from Urakami—visited the ruins of the cathedral before returning to his monastery in Hokkaido. He began digging around the debris in search of some artifact from his church that he could bring with him. He came across a remnant of a beloved painted wood statue of the Virgin that had been brought from Italy in the 1930s; all that had survived the bombing was her head.

The “Madonna of Nagasaki” is now on display in the rebuilt Urakami Cathedral, erected on the site of the destroyed church. When it was brought to New York last year, Archbishop Dolan said:

The “Madonna of Nagasaki” is now on display in the rebuilt Urakami Cathedral, erected on the site of the destroyed church. When it was brought to New York last year, Archbishop Dolan said:

And it is this head that is haunting: she is scarred, singed badly, and her crystal eyes were melted by the hellish blast. So, all that remains are two empty, blackened sockets.

I’ve knelt before many images of the Mother of Jesus before: our Mother of Perpetual Help, the Pieta, the Virgin of Guadalupe, Our Lady of Lourdes, just to name a few.

But I’ve never experienced the dread and revulsion I did when the archbishop showed us the head of Our Lady of Nagasaki …

Again, it was not possible to drop Fat Man and Little Boy without intentionally incurring these results. I ask myself, If I were president of the United States, could I knowingly incinerate the faithful at Mass or priests hearing confessions? Could I vaporize or melt down chapels and chalices and tabernacles and icons? And knowing that such acts would be multiplied and multiplied again, killing thousands upon thousands of innocents, could I intentionally bring about such destruction in a matter of seconds? No matter how much it would benefit my country? I don’t think I could.

But then again, I’m not president—nor would I want to be. If I read Fr. Miscamble’s post correctly, his conclusion is that while the decision to drop the bombs was not moral, it was simply required of Truman by virtue of the office he held. And I think I may be at the same place: that it was immoral of Truman to order the bombing, but that it was the right thing to do—or at least justifiable—as an act of presidential leadership. He has blood on his hands, but the job he held sometimes requires the immoral staining of one’s hands with blood. (That’s why it’s a job I wouldn’t want.)

For the record, I’m not a pacifist. (Indeed, far from it.) I’m not anti-nuclear; in fact, I think Japan’s move away from nuclear power in the aftermath of Fukushima is economic suicide (but that’s another post). Nor am I anti-American and, again, I’m not convinced that using the a-bombs was the wrong thing for America to do in the context of a hideously brutal war. But I wonder if sometimes those of us who resist the traditional hostility to the use of the bombs don’t go too far in defending the morality of the decision, failing to distinguish what would have been prudent (and justifiable in the name of prudence) from what was morally right.

This applies to the present day as well. Decisions that make perfect sense as a matter of tactics, or grand strategy, or self-defense, or national interest are sometimes whitewashed as moral acts. The result is that, in order to defend, say, a particularly unpalatable act of war, we contort ourselves into all kinds of strange justifications that do a disservice to both our perception of morality and our appreciation of what war—and wartime leadership—really requires.

So I’m curious to know what others think of this divide: between what is demanded by presidential leadership and by other forms of responsibility for a nation’s safety and well-being, and what is strictly moral, especially in times of war. Some, I gather, will think that no responsibility can truly demand immorality. I’m not convinced of that—yet.

Thanks to readers for putting up with the long (and meandering) post, and thanks to Fr. Miscamble for opening and contributing to this discussion. I look forward to reading his book soon, now that it’s no longer $80 on Amazon.

Published in General

Meghan, for most of your life you were right, but now seem to have lost the plot.

We have the luxury of agonizing over such moral questions because of Mr Truman’s gutsy decision – the buck did really stop with him, and how nice to have a President who believed in leading from the front.

My father, now 87, often tells me that he was training for the invasion of the Japanese mainland when the bombs were dropped. He, like countless millions, would almost certainly not have survived that invasion. He had a number of friends who survived the horrors of being Japanese prisoners of war.

I think we in this generation cannot understand what happened just before we were born – but we should respect Mr Truman’s decision, and his morality.

To use them at all was to knowingly obliterate an entire city, and thus to intentionally target innocents—something of a different nature than regrettably accepting the possibility of “collateral damage” that might or might not materialize when attacking a non-civilian target.

Meghan, you’re quite wrong about this. The bombing of German cities was specifically labeled “area bombing,” which we distinguished from precision or targeted bombing. We actually constructed fake German cities — replicating the typical wood and brick buildings of German cities — and bombed them scientifically, employing a welter of methods of bombing, precisely for the sake of achieving the greatest breadth and quantity of civilian damage — and carnage — that such bombing campaigns could yield. Read Jörg Friedrich’s The Fire: The Bombing of Germany 1940-1945, Columbia U Press.

Dresden, Hamburg etc. after being bombed looked exactly the way they would had we dropped LIttle Boy and Fat Man on them.

I agree, however, there is the obvious difference of the gruesome radiation fallout. But otherwise we’re speaking purely of differences of efficiency of killing/destruction, not apples and oranges.

“War is cruelty, you cannot refine it.” W. T. Sherman

“These weapons are apples and oranges. Little Boy and Fat Man could not be limited to specific targets; they could not be intended only for, say, dams in the Ruhr industrial region or a particular Mitsubishi aircraft factory.”

By 1944 or so, it had been realized that pinpoint bombing with conventional bombs was a chimera…even with the best technologies of the day, bombing was highly imprecise, and for that reason the decision was made, on both fronts, to pursue area bombing targeted at entire cities. My post Dresden describes the secret British debate about this strategy.

See also deterrence, which is about massive retaliation in the nuclear age.

Meghan, you’re quite wrong about this. The bombing of German cities was specifically labeled “area bombing,” which we distinguished from precision or targeted bombing …

Dresden, Hamburg etc. after being bombed looked exactly the way they would had we dropped LIttle Boy and Fat Man on them.

Edited on Aug 07 at 02:44 am

Robert is entirely correct about this.

There are many reasons to look back upon that war with horror and nausea, and it is not wrong to contemplate, in vivid detail, the effects of an atomic bomb or to feel agony for its victims. I wish more people would, because it might snap them out of their somnolence.

The greatest cause for moral regret about our conduct in the Second World War, however, I would say is this: We could have bombed the train tracks to Auschwitz. We did not.

This is also why “smart” weapons are less “moral” than traditional weapons. They are suitable in some situations, but they have given credence to a bankrupt ideology that civilians should never be hurt or even inconvenienced in war.

In a just world, these should be the first people hurt, killed and especially inconvenienced. No government can stay in power without the support of the people. No dictator can stay in power if the people are united against him. Who is most morally responsible for stopping a dictator, his own subjects or the other nations he might attack?

Hold on. This sounds like a justification for terrorism. In fact, it resembles one to a great degree.

Yes indeed, governments can stay in power without the consent of their people. That’s what “tyranny” means.

Claire…bombing the train tracks to Auschwitz.

I agree that we should have done this; however, railways in WWII prove remarkably resilient against aerial attacks. Unless you were lucky enough to hit a key bridge, they were back in operation very soon It’s unlikely that sufficient damage could have been done on a continuing basis to put the camp out of operation.

It is possible, though, that such attacks combined with a heavy leafleting campaign about what was going on in the concentration camps *might* have had a meaningful effect on the will to resist in Germany.

Thanks for a great, thought provoking post. I would agree with Claire and Robert that much of the bombing in the ETO was quite indiscriminate. The British basically carpet bombed at night to avoid the inherent greater loss of aircraft from daytime raids. As far as the use of atomic weapons to effect a quick end to the war, I’m not sure I understand the moral dilemma. What was the alternative? The decision not to use them would have resulted in far greater loss of life and suffering. I’ve heard it suggested that a demonstration bombing of a remote area could have convinced the Japanese to surrender. But since there were only two bombs in existence, I don’t think this was a reasonable alternative. Truman really had no choice. And his decision saved many lives.

Beautiful, thoughtful post, Meghan. Just as we need “deciders” in political leadership, we need contemplatives and ethical ruminators in our cultural life.

Leaders don’t spring from thin air. They are formed by a culture.

I’d like to add another book to your recommendations: A Song for Nagasaki. It’s about a Catholic radiologist who lived and worked in that city, and eventually died of radiation poisoning. He gave a beautiful and moving spiritual interpretation of what his beloved city suffered.

My own “opinion situation” is just like yours. I was raised by a father who staunchly defended the bombings. Only later, under the influence of my theology and philosophy studies have I grown to doubt their justice. Like you, I’m glad not to be the one with the responsibility.

I agree that we should have done this; however, railways in WWII prove remarkably resilient against aerial attacks. Unless you were lucky enough to hit a key bridge, they were back in operation very soon It’s unlikely that sufficient damage could have been done on a continuing basis to put the camp out of operation.

It is possible, though, that such attacks combined with a heavy leafleting campaign about what was going on in the concentration camps *might* have had a meaningful effect on the will to resist in Germany. ·Aug 7 at 4:59am

I’ve concluded after studying this more closely that you’re right. See my post above.

Hold on. This sounds like a justification for terrorism. In fact, it resembles one to a great degree.

Yes indeed, governments can stay in power without the consent of their people. That’s what “tyranny” means. ·Aug 7 at 4:51am

In WWII, the nazis and the Japanese were clearly wrong. In the war on fanatical islam, Al Qaeda is clearly wrong.

I don’t buy into moral equivalence. You can’t equate punitive actions against Al Qaeda and its supporters, including civilians, with the manner in which Al Qaeda melts skyscrapers or mutilates children in front of parents.

You don’t win many wars by limiting your methods to the Marquess of Queensbury Rules. What the result has been is our Marines and soldiers fighting for almost ten years with both hands tied, using extremely expensive armaments. We spend billions for every thousand the enemy spends. We are not bound to these tactics. The moral side has the right and the obligation to win. If anyone is to die in a war, the onus should be on those who are on the wrong side and supporting evil regimes.

As for your definition of “tyranny,” I disagree. That a tyrant does take control in no way excuses the people for allowing it.

If I were to meet a man who beats up little old ladies and steals their purses, and threatens me and punches me in the nose, and who threatens to do much worse, and I then give that man a gun knowing that he’s going to do worse, am I free of guilt? No. I am obliged to fight back and not arm him. I may not succeed, but the more that fight him, the less success he’ll have. If no one ever helps him, he will get nowhere.

The first line of defense against tyrants is the people. It may be more comfortable to acquiesce to the tyrant, but that doesn’t make it right. The people have an obligation to stop him at all costs before allowing him to attack others. Just because it’s hard to do is no excuse for not succeeding. Live free or die.

Meghan, excellent post. However, I agree with the Catholic moral position that Ed Feser staked out in January 2011, where the attack was unjustifiable regardless of the office Truman held.

I do not think war is a good thing; it is often a necessary thing. The use of atomic weapons ended the war quickly. Less people died. If your goal is less dead and maimed kids, then get the war over as fast as you can, with whatever you can.

Wars only end when one side stops fighting.

I wonder if the distinction I’m making is too subtle, but based on the comments, I want to reiterate it nonetheless:

My current position is that it was probably right for Truman, *as president of the United States, responsible for the lives of our troops and for the security and global interests of our nation*, to use the bombs. Whether it was moral–right for him as a human being with a soul to account for–of that, I’m less certain.

So as for the arguments in defense of Truman’s using the bomb: Mostly, I don’t think we disagree. As president, he probably had to.

The broader question I’m trying to get at is whether being president required him to suspend strictly moral judgment. (Also, I’m coming at this from a very specific framework for defining morality, which was not Truman’s.) In other words, is acting immorally necessarily part of the job description for someone in such a position of leadership?

I would suggest that someone with your concerns should not run for president. For a president, the concerns you raise are too precious. Now, for a person on the street, in the trenches, on the beach, your views are likely to find many a willing adherent. And that is their only hope.

It seems to me impossible to judge an act as moral or immoral without first establishing exactly what the moral is. If the moral is to not willingly or willfully take another human life, then no act of war can ever be judged as moral. If the moral has a sliding scale such as not taking another life unless ______, then I have difficulty grasping it as a moral at all. Most of the arguments for the morality of the bombing strike me as merely utilitarian calculations dressed up as morality. I suppose this is the problem with having a rigid, binary understanding of morality. Having said that, I’ll get back to studying the concept of morality to see how far I’m off on this.

I’m glad you weren’t the President in 1945. Hindsight, easy. Fighting a nation of brainwashed suicidal zealots, not easy.

Continued (ah, Ricochet comment limits):

Part of why I’m curious about this is because I think we have a tendency to seek to justify as moral things that were not moral, but were necessary. For some people, what is necessary (or simply advantageous–the lesser of two evils) *is* moral. That’s not how I define it, though, and I suspect that’s not how a lot of other people define it, either.

The danger in this, I think, is that it actually cheapens our appreciation of what people who are responsible for defending us have to do on our behalf. Many of us, particularly on the right, argue that whatever is done in America’s interests is morally right. I think that is by and large true because of the way America conducts itself in war, and because of the amazing heart and discipline and honor of our troops. But it is not *always* true; the a-bombs, I think, may have been an exception.

And to the extent that we reflexively back-justify strategically necessary actions as moral ones, we fail to recognize the sacrifices of people who place our safety above their own comfort of conscience.

And one more thing: This tendency has, I think, conditioned us to want to be able to call every act of war done on our behalf as “moral.” This opens the door to significant outrage when necessary acts of war are perceived as not moral: See Vietnam. In other words, a practice that many of us on the right champion opens the door to anti-Americanism from the left.

I think it would be better to separate utility from morality, and have a quiet appreciation of the fact that what it takes to win wars will not always allow us to sleep soundly at night. This prevents two extremes: Papering over horrific and likely immoral acts (like the a-bombs), and also tying the hands of our defenders to the point that they can do only what the professional ethicists approve.

The middle way–and, I posit, the healthier way–is to accept the decoupling of morality from necessity. Currently, that’s how I’m approaching the a-bombs.

First: Skyler, you’ve got me thinking…. I understand your points very well. Think about the cultures of Germany and Japan of that time. They prided themselves in their strong social ties to each other. They both have histories replete with examples of how their solidarity has served them well. This works better in hindsight than in a prescriptive manner — because it is subject to abuse by leaders if one is not vigilant in selecting said leaders. In fact, an unthinking solidarity is amoral (and perhaps immoral) in itself.

The German and Japanese cultures were the source of these countries’ incredible successes in the early phases of the war. So — the people are culpable if they have developed themselves into a sword (a good thing) and yet are indolent in their choice as to who will wield it.

Now, Claire’s point about this being close to giving excuses for terrorists: If you accept the world view of the terrorists, then my above discussion has to apply here, also. The reason we call them terrorists is because we judge (and know) them to be wrong about their reasoning. But, we must fight them all the same until right reason prevails.

Thanks for the recommendation, katievs. I had actually ordered that book from Amazon a few days ago (I’m planning to visit Nagasaki in the fall), along with Takashi Nagai’s own memoir, the Bells of Nagasaki. (Semi-related, I understand that the “angelus bell” of the old Urakami Cathedral was one of the few artifacts to survive the bombing and ensuing fire; I think it still rings out from the new cathedral built in its place.)

So now I’m really looking forward to reading the books; thanks for validating my Amazon habits.

“But I wonder if sometimes those of us who resist the traditional hostility to the use of the bombs don’t go too far in defending the morality of the decision, failing to distinguish what would have been prudent (and justifiable in the name of prudence) from what was morally right.”

Presidents have a moral obligation to protect their citizens including their soldiers. Ending the war victoriously as quickly as possible–using these immoral weapons–was both prudent and morally right.

Over the course of history more people, exponentially more people (especially innocent people) have died terrible, immoral deaths from the blades of machetes than from nuclear weaponry.

There are no particularly palatable acts of wars. Killing is a terrible thing but when you fight, you fight to win. Winning is better than being forced to accept your enemies terms of surrender. The Axis Powers, or even the Reds for that matter, certainly would not show the same level magnanimity the US did. In war your choices are bad and worse; Truman chose bad, thank God he didn’t choose worse.

Robert Lux and Claire: Good point about the area bombings. Those, too, were horrible; the most memorable thing I read senior year of history in high school was a series of essays on the Dresden and Hamburg bombings, and about the effects of the firestorms that they provoked.

My point, though, is that any *one* conventional weapon used to take out a military target was not comparable to the *one* atomic bomb. That it was possible to use a conventional bomb (even though the Allies in those cases chose not to) without intending for your casualties to be mostly civilian–something simply not possible with the a-bomb.

And though I’m not a historian, from what I’ve read of accounts of both the Dresden and Hamburg bombings and the bombings on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, I do still think that the atomic weapon is simply in its own category of destruction. Call them kumquats and oranges if you like, but they’re still not the same fruit…

Agree, Claire, that the more grave moral failing in the war was in respect of the Holocaust. There were several discrete failures to act that, combined, produced the larger failure. But I think the most serious had nothing to do with military action; it would have been an entirely bloodless way of saving untold numbers of lives. Why didn’t we completely open our shores to the Jewish refugees fleeing the Nazis in the years leading up to the war and during?

Meghan: Morality, like almost all things, must have a prioritization imposed on it. It is not a dual thing of utility vs. morality. It is that the highest moral position must be selected and acted upon. That prioritization is a moral issue in itself.

When a person raises his hand and swears to uphold his oath of office that is (unless he is crossing his fingers) the highest moral position upon which he acts — at least insofar as his duties as president are concerned.

Truman’s personal moral situation is enhanced when he carries out his duty. It is further enhanced if he does it in the face of personal reticence. As an individual a president can resign — that is an option. But, it is not an option morally to decline to do one’s duty. Instead, one’s duty — in your example — is to resign. That is the only moral alternative left to a president in this most difficult of decisions — the most difficult decision that any president has ever had to make.

…

If someone had the means to prevent these things, and declined to act, does he not have blood on his hands as well? ·Aug 6 at 11:18pm

Good point about the nukes, James, though to play Devil’s advocate: Four years after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, we no longer had a monopoly on the bomb (and relative peace intervened). After that point, there was a counterbalance, and the bombs got progressively worse; the end of WWII, it could be argued, was the only narrow window in which a-bombs could be used without MAD.

And, yes, failure to act can be just as gravely immoral. It just seems that in war, a president is going to have blood on his hands; the question is how much. (Have addressed the moral/necessary distinction in other comments.) It’s why I’m grateful not to be president, and very (and humbly) grateful for people who make those decisions for me.

Interesting, Larry–I gather that your argument is that when a man takes the oath of office, his highest moral obligation is to his duties as president, above all other competing moral claims?

I suspect many will agree with you. I wonder, though, what this implies for seriously religious candidates (especially given the degree to which religion is used on the campaign trail). Does a president absolutely need to put Country before God from the time he is inaugurated until the time his successor is? I wonder if the question were put to all of today’s GOP candidates–As president, would you put Country before God?–how they would answer; I also wonder how the public would respond to those answers.

Meghan, I categorically deny the sophistry behind this popular notion that atomic bombs (or hydrogen bombs) are different than any other weapon — except in scale. Once one deals with the horrors of the scale then nothing more needs to be said about them. They are weapons of destruction — mass or otherwise.

I defy you to explain how they can be so defined that they can be revealed as a unique killing tool. I already said I don’t accept “scale” to be a categorical issue — it is just a multiplier.

I remember belonging to a Protestant denomination during the 80s that issued a pastoral letter decrying even the mere possession of nuclear weapons as a deterrent. I responded with a letter to the bishops asking if they also believed that using such force as was required to secure the freedom of bishops to write asinine letters was also immoral. No response.

During Desert Storm, this same group of bishops labeled us as aggressors, and denounced us. That was going quite too far for my tastes. I left that denomination with another letter, this one pledging my continued military service in an effort to buy sufficient time for the bishops to regain their moral equilibrium.

This sort of analysis and introspection is interesting and useful, but would be impossible were it not purchased in real time, in real blood, by people willing to do violence on your behalf.