Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Should We Worry about America’s National Debt?

Should We Worry about America’s National Debt?

Of course, Ronald Reagan said the debt is big enough to take care of itself. Still, that headline question is the exact question I asked economist Ken Rogoff last November. From our exchange:

Published in EconomicsRogoff: Well, obviously one question is at what horizon are we borrowing? So if you’re borrowing at 30 years, you can certainly carry – it’s a lot less risky than if you’re doing all quantitative easing and you’re borrowing at overnight interest rates when those can change on you very suddenly.

Anyone who thinks we’re never going to have inflation again, there’s no risk that interest rates will go up, that’s nuts. We’re not – the United States is not a hedge fund and not just saying, well, there’s a 5 percent chance we’ll go bankrupt, to the 95 percent chance we’ll make money. We have to balance those risks and think about not just the level of debt, but what is the whole maturity structure of debt, what’s the profile. It’s pretty short at the moment after all this period of quantitative easing.

Clearly the U.S. is in a position to take on more debt, and I think if you do it on infrastructure spending, improving education, it’s really – I think would be a good idea. On the other hand, if you say, you know, we’re never growing again, we’re in secular stagnation, so let’s just have a big party now and we’ll worry about it later, that’s kind of crazy. It’s just –

Pethokoukis: If I were to tell you that this US debt ratio in 2040 was doubled, it was 150 percent of GDP, if that the only data point that you knew, would you be able with any confidence be able to tell me anything else about the economy if you knew that one statistic?

No. I wouldn’t because we also have the unfunded pension liabilities that have very similar properties to debt. We’d need to know the maturity structure of debt. You need to know a lot of things. The United States is clearly in a much better position than countries like Italy, even France, Greece. The United States is still the world currency and can do much more.

But it’s a question of the profile of risk. You say a lot of people on the left favor having more debt. I guarantee you if the right is in power and they’re doing things that create more debt, the same people on the left would be saying that is terrible.

I’ve heard economists say that perhaps in the future we’ll be like the bank of Medicis in Renaissance Italy where people will just want to hold US bonds as a place to put their money. They could care less that the interest rates are low or negative. They’re just looking for a safe haven in a dangerous world and, therefore, rates will be low forever, and as long as we’re not doing crazy things with the money, now is the time just to be spending what we need to spend. We still care what the debt-to-GDP ratio is. We’re still, you know, dying over each – you know, the CBO updating their long-term budget outlooks and that is just missing sort of new environment we’re in.

Are we really obsessing about it? I mean, when Mitt Romney ran in 2012, he was going to have a huge increase in debt on what Republicans wanted to spend it on. Trump is going to have a huge increase in debt on what he wants to spend it on. The Democrats are going to have a huge increase in debt on what they want to spend it on. And a lot of this conversation about – you know, worrying about debt is actually the side that’s not in power complains about it because they want to be able to spend the money, they want to be able the way they want to spend it. So I tend to think that that caricature that somebody’s worried about debt tends to sort of miss where the real debate is. I think –

I think to the extent we’re spending it on pre-school, early childhood education, to the extent we’re spending it on useful infrastructure, that’s an investment and it pays off and you can carry it better. And on the other hand, to the extent that you really believe, as many on the left do, that we’re not growing anymore and we should just consume as much as possible now in sort of pure consumption, that’s a harder case to make. And, again, you have to look at the maturity profile of debt and not just at the level of debt. It’s a risk management question. That’s the core of the issue.

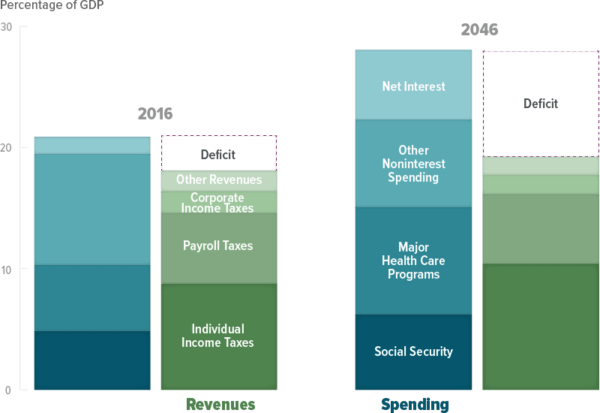

What Rogoff is getting at is that it isn’t the level of the debt it is the debt service. The problem is that interest rates look like they may normalize before the level of debt to GDP drops. In that situation the debt service becomes an unmanageable fraction of the federal budget.

When a philosophical question comes up I recommend to first ensure that the question is clear before I try to answer it.

To start, what’s the universally, permanently verifiable definition of “debt”?

We all understand what it means in the case of an ordinary person having a debt to another ordinary person:

But obviously that definition would need to be clarified if

No. It’s only money.

When the ten year treasury hits 4% the USA is broke. Human needs won’t be met. When it hits 5.25%, interest is the largest expense on the budget. Somewhere in there a bunch of financial bubbles implode.

All Western countries will engage in covert and overt forms financial repression until chaos breaks out.

David Stockman’s new book is a masterpiece.

How to service the debt is one question. The bigger issue is spending, and as noted, every politician wants to spend money. If we’re borrowing 40% or so of every dollar spent, we increase the risk to be able to spend in the future with every additional dollar spent.

If interest rates pop, the debt service will eat up so much of the budget that the only significant spending will be on debt service, and we’ll be sitting back wondering how we got to a point where debt service became 50% of the budget. The incentives for politicians are always to do more, to spend more. They are incentivized to do the one thing that has the biggest long-term risk of imploding the economy, and since it never happens today, only tomorrow, there is no short-term downside to spending.

At some point, a grown-up has to stop annual spending increases from the historic 2x/3x the rate of inflation. In fact, I’d like to see the opposite – a drawdown of spending. A long, slow glidepath of a decrease in spending.

In 2017, interest will be 7% of the budget. 4 years later, it’s 11%. We’ll be crowding out the rest of the budget. Tack on unfunded liabilities and the ability of the gov’t to do anything other than service debt from tax receipts and process transfer payments for entitlement spending will be reduced to not much at all.

Of course we should worry but it’s not that difficult to fix. We don’t have to pay it off, just look like we have it under control with shrinking deficits resulting from sustainable policies. The focus should be on ceasing to do dumb wasteful things by cutting the budget, privatizing entitlements and raising revenues to cover those already on SS, getting medicare or close to or receiving them.

The Fed is going to pay for all of the broke state government pensions and Medicare. There is no combination of inflation and growth that will “defease” our obligations.

Amen. It is likely that by the end of Trump’s first term and almost certainly by the end of the next presidential term that transfer payments and interest will be 100% of federal revenue. Everything else the government does will be debt financed.

Which goes into the one reason pre-election I saw for voting for Trump: given his willingness to screw over his bond-holders in his business, I think he is likely the only president willing to make the entitled take a hair cut. When given a choice between having less money to spend or not giving money to people expecting it, he goes with the former. And as president, the only way he will have any revenue to play with will require not paying entitlements.

As they say, “It’s complicated.” Bondholders are not all the same. Some, probably a large fraction, are simply looking to park money with a promise of a far future pay out. From their perspective, the bonds represent an important stabilizer in an investment portfolio. As long as there is the illusion a repayment — they’re good. Other bondholders, probably only a small portion of holders, are looking at very time specific cash outs. So long as there is a way to get them their money, on time, confidence will remain high and the system will remain stable. And it doesn’t hurt for the rest of the world to stay a basket case financially.