Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Why Are We So Dumb About Healthcare?

Why Are We So Dumb About Healthcare?

When Sarah Palin first started talking about “Death Panels,” I cringed: Not because the prospect of a government panel empowered to make medical decisions on citizens’ behalf wasn’t totally creepy (it was) but because private insurance does the same thing. Now, I’d argue that a system based on free-market, private insurance has, regardless, enormous advantages to the alternatives, but this doesn’t mean that private insurers don’t sometimes need to be cold-hearted bastards. The sad fact of life is that there’s no way to pay for top-end medical care for everyone, so some form of rationing (even the free-market kind) is inevitable.

When Sarah Palin first started talking about “Death Panels,” I cringed: Not because the prospect of a government panel empowered to make medical decisions on citizens’ behalf wasn’t totally creepy (it was) but because private insurance does the same thing. Now, I’d argue that a system based on free-market, private insurance has, regardless, enormous advantages to the alternatives, but this doesn’t mean that private insurers don’t sometimes need to be cold-hearted bastards. The sad fact of life is that there’s no way to pay for top-end medical care for everyone, so some form of rationing (even the free-market kind) is inevitable.

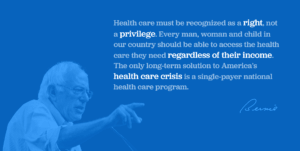

But for some reason, nearly every society tries to pretend otherwise. Some of this can be explained away as leftism, but it always seems to hit healthcare the hardest? Consider, for example, how Senator Bernie Sanders made “Medicare for All” a major part of his platform, but not “SNAP for All.” Via Megan McArdle, part of the answer may be that human beings are hard-wired to see providing healthcare as a social good in itself, rather than treating the matter as service we trade for. From a paper by economist Robin Hanson, whom McArdle cites, this may explain many of our irrationalities regarding health care:

[H]umans evolved deep medical habits long ago in an environment where people gained higher status by having more allies, honestly cared about those who remained allies, were unsure who would remain allies, wanted to seem reliable allies, inferred such reliability in part based on who helped who with health crises, tended to suffer more crises requiring non-health investments when having fewer allies, and invested more in cementing allies in good times in order to rely more on them in hard times. These ancient habits would induce modern humans to treat medical care as a way to show that you care.

As he points out later:

It is notable that … while some charity behavior is outcome-oriented, much other charity behavior seems oriented more to creating the appearance of charity efforts. [Specifically,] it seems to me that politicians and others considered for positions of influence in health policy are frequently selected in part for how much they care about health. In contrast, it does not seem to matter much whether people who regulate electric utilities, for example, care much about electricity.

In The Fatal Conceit, F. A. Hayek* suggested that the values essential to success in small-scale societies (“solidarity, altruism, group decision, and such like”) are inappropriate when applied to a modern, macro-society, where values of “savings, several property, honesty, and so on” become far more important. This is no less true for health care than for other matters, though seeing that clearly seems to be particularly difficult.

The sooner we figure this out, the more people we’ll be able to help.

* Just that sort of morning, I suppose.

Published in Healthcare

The problem with this is inflation. Actual health care is a slowly growing supply. Inherited unused funds are too likely to grow faster, especially for the vast majority of the population generations that are fundamentally healthy. Even if only growing a little faster, it’s the nature of exponential growths–which (inherited) funds will be–that the slightly larger exponent won’t take long at all to vastly outstrip the slightly smaller exponent–and the exponent on the growth rate of the supply of health care will be close to zero; the supply will grow close to linearly (other than discontinuous jumps from one linear level to another through technological advances).

The outcome of this is that the money available to buy health care will quickly outstrip the supply, and the price of health care will inflate very rapidly–and the poor, who won’t be able to build up much inheritable health funds, or the unhealthy, who will burn their funds as fast as they accumulate them, will quickly be priced out of health care.

Better in this venue to let each generation start its health funding anew; inherited funds should be part of the general estate. Everyone will still be forced to consider their end-of-life decisions as rationally as they ever have been.

Eric Hines

Sounds good to me. Anything that creates proper incentives is okay in my book.

Too bad Hayek didn’t have a chance to talk to me about it. I’m certain he would have loved my scheme described in #5.