Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Do You Want Fries, or the Extended Warranty, With That?

Do You Want Fries, or the Extended Warranty, With That?

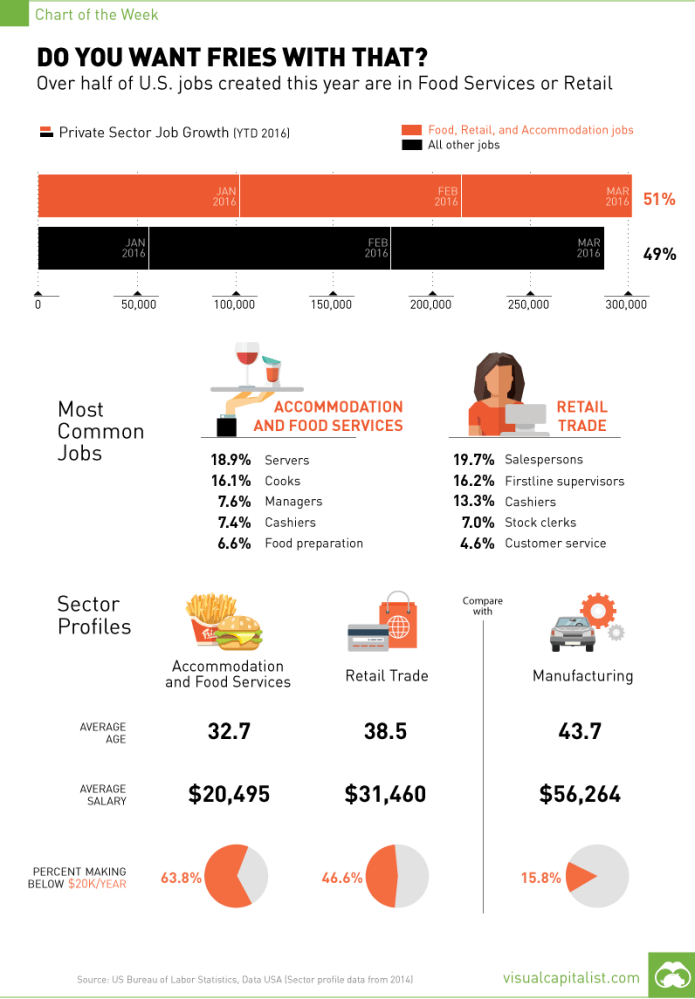

Here, from Business Insider, are where the jobs are:

I’m surprised here by two things: The first, that retail is such a big deal, and that the average salary is higher than I expected. It’s not broken down into part- and full-time categories, but still: for the average, it’s higher than I expected in an environment where consumer spending seems to be slack. My guess is that it’s a (messy) combination, but still interesting.

The second thing that surprises me is the relative resilience of manufacturing, which is probably another vague category that includes construction, but it suggests that all is not totally lost.

So, two questions:

- Assuming that it’s a good thing, how do we get manufacturing jobs inching up higher than food/hospitality/retail?

- Can we really be a nation of primarily shopkeepers/food service workers/hospitality workers? Does this graph confirm the evidence of your eyes and ears? I’m not sure it does for me, but maybe that’s a case of my not wanting to see what I don’t want to see.

I did, and I have no illusions about how dull factory work can be. When I was a teenager, I worked in a factory for a time assembling wiring harnesses for cars. But if you worked for a good company, you moved up to higher paying, higher skilled work after awhile. Less drudgery, more expertise. Even if a factory automated more, you could move into robotics, machine-tooling, etc. Good jobs with a future.

That factory I worked at? Gone. Closed and moved to Mexico. Cheaper labor. Nothing like it replaced it.

That’s why the free trade argument in a vacuum fails. We don’t have a free market in the first place. When jobs are lost because it’s cheaper to automate, is it because automation is really cheaper, or is it because government piled on so many new regulations that it made automation cheaper? When the government pushes policies that drives up the cost of employment then pushes policies that makes it easier to send those jobs somewhere else, the arguments for free trade and the reality are out of sync. Those losing their jobs only know that they got the shaft from both sides. That doesn’t even consider other factors like pension costs, union interference, etc. We have been making free trade agreements based on a free market which we don’t have. Given the backlash, we should be questioning if we’ve overlooked some of the costs in making assumptions that were wrong.

Agreed.

Bit of both, in my experience. But the tech curve has been making it cheaper and faster.

There is a post I’ve been meaning to write, but haven’t had time to finish the research, on Ford’s recent move of low end car production to Mexico and how it relates to their recent UAW “negotiations”. The NLRB takes a huge amount of blame for what happened here.

When it comes to labor, this is absolutely true.

One factor that I wish was discussed more was the capital investment side of things. I wonder greatly about factories like yours in this regard. Not too long ago, if you invested your profits in heavy equipment, you’d have to write the equipment off over 20 years, which is quite a gamble. Now, frequently you can write it off in far less time, which makes equipment purchases far more feasible and less risky.

In the case of the harness maker – I imagine their scenario was this: As a union shop, the union would have fought against any automation, reducing or eliminating labor savings, be tied up in red tape and permitting, and the investment would be heavily front-loaded to boot – so a factory upgrade would be both prohibitively expensive and not pay off for a decade or 2. OTOH, building a new plant in Mexico might cost the same as the upgrade, but be held up less by red tape, be union free, and you would save money right away on labor.

Good points. Years ago, someone floated a plan to pay people for access to their (anonymized) medical records. The idea was that our data set is skewed in that area — we only really study and collect information from sick people. We really don’t know how many people “have” cancer or “have” heart disease — we only know how many people are sick from those things. There may be lots of folks with slow-moving cancers that never make trouble, as long as the patients don’t live to be 150 or 200 years old.

Someone once even suggested paying a bounty on your dead body — selling it to science as opposed to donating, yielding many more bodies to study.

Couldn’t the feds do something like that with employers? Give them a small incentive to report in depth on their quarterly numbers, including better categories and more specific detail?

Data, is, after all, the only way to know what’s going on in an economy this large.

I’m in a right-to-work state in the South. There was no union. We already had lower labor costs than northern states like Michigan or Illinois.It was simply a matter of “Hey, we can do this for pennies on the dollar in labor costs in Mexico, but still make the same profits selling in the US”.

It was simply about profit. Companies should profit. That’s why people work. But let’s not pretend that this can all justified with some formula from a textbook. The calculation was simple

“NAFTA passed. That means we can close the factory and move to Mexico, but still sell in the US. But it also means firing all the people here in the US.”

“Fire ’em. Their problem, not ours. Other people still make enough to buy our stuff. Those lawyers still buy cars.”

“Yeah, about those lawyer jobs…”

Speaking of factory closures, I am reminded of one related by a friend of mine at GM. Michigan had, for a time (and may still have), a law on its books regarding company relocations. The law allowed cities in Michigan to block intra-state (i.e. within Michigan) company relocations if the township losing the plant deemed the impact too high.

Well, this particular supplier was located in Flint, but wanted to move to a better site in Grand Blanc, which is adjacent to Flint and much nicer (this would be like relocating from Gary, IN to Crown Point, IN). No one would have lost their jobs, and the commute might have been an extra 10 minutes. Flint blocked the move, claiming that the tax penalty for them would too high an impact, nevermind that employees mostly already lived in Flint and paid Flint taxes.

Well, this supplier then unveiled plan B. They had been heavily recruited by Arkansas, and all they needed to do was sign the papers. So they pulled up stakes from Flint, and nearly everyone lost their jobs, save for the top brass who could afford the move.

Flint’s protectionism cost them dearly.

Thanks for the clarification.

This is a major truth. We (or I) keep forgetting that the way America zoomed ahead in the post-war boom years was, first, everyone else was a pile of rubble.

Interesting to note: part of the 1970’s-1980’s boom in Japanese car manufacturing was caused by trade deals struck in the 1940’s, where American policy was to create big incentives for Japanese vehicle and engine manufacturers to convert to peacetime product lines. My beloved Subaru started life, in a not-so-contorted way, as an aircraft manufacturer under Fuji Heavy Industries.

Did they let Flint know about plan B when this was being negotiated, or was it always their intention to move and use Flint’s recalcitrance as cover?

Okay, so to synthesize all of this, let’s assume three things:

Okay, so assuming that: what do we do? What can 51% of us — and America — agree on to meet these changes?

This is why the postwar economic dream was unrealistic in the long run. The gravy train started slowing down when cars hit our docks from Germany and Japan, and Boeing and McDonnell Douglas suddenly had competition from Europe. It’s easy to be an economic juggernaut when you’re the only game in town, and the rest of the world is climbing out from rumble for two decades.

Well, let’s not be too quick to dismiss that 6-year conventional bombing campaign I mentioned.

I’m not sure of the full details in that regard.

Edit: I think, but cannot confirm, that the company had in fact already purchased the site it wanted in Grand Blanc, had gone through all of the pre-work needed to grease it along. But I could be mistaken on this point.

DOUBLE LIKE!

This means my dream of writing the great American movie about the restaurant business is closer to coming true!

Brother, you don’t know the half of it. If anyone’s kid is thinking of going to law school, beat them with a stick until they come to their senses.

We’ll send them to Amy Schley, and she’ll beat them with a shoe.

I know where manufacturing jobs are going because I’ve seen a show called “How It’s Made.” I am neverendingly amazed at the quality and quantity of automation in manufacturing.

My friend’s mother worked for a time at a clothing manufacturing shop (a very, very, *very* short time – she hated it) and they literally put denim fabric on sewing machines and sewed up the seams. A How It’s Made episode on the manufacturing of jackets showed the computer laying out the fabric, cutting it and sewing it. Every seam was perfect in every way and no one got a needle through their finger.

I fail to see how we’ve lost anything of value with this particular loss of jobs. We are only bemoaning the loss because the idiots who run our government are interfering with the creation of new ones.