Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

China and the Thucydides Trap

China and the Thucydides Trap

Graham Allison is probably best known to you as the author of Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis. I’ve always held him in high regard: He’s the old-fashioned, careful kind of political scientist (this as opposed to the new-fangled, addled-by-idiot-theory kind).

Graham Allison is probably best known to you as the author of Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis. I’ve always held him in high regard: He’s the old-fashioned, careful kind of political scientist (this as opposed to the new-fangled, addled-by-idiot-theory kind).

I just finished reading his very thoughtful and provocative article in The Atlantic, The Thucydides Trap: Are the U.S. and China Headed for War?

It’s very worth reading in full, but this is the gravamen:

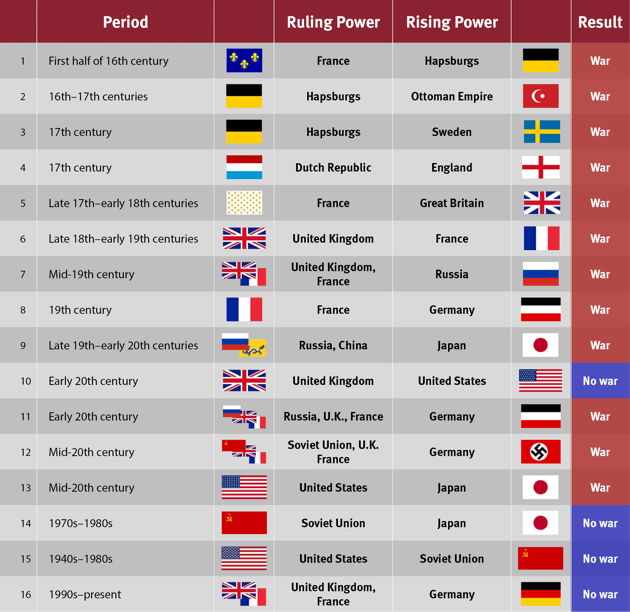

The Greek historian’s metaphor reminds us of the attendant dangers when a rising power rivals a ruling power—as Athens challenged Sparta in ancient Greece, or as Germany did Britain a century ago. Most such contests have ended badly, often for both nations, a team of mine at the Harvard Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs has concluded after analyzing the historical record. In 12 of 16 cases over the past 500 years, the result was war. When the parties avoided war, it required huge, painful adjustments in attitudes and actions on the part not just of the challenger but also the challenged.

Based on the current trajectory, he argues, “war between the United States and China in the decades ahead is not just possible, but much more likely than recognized at the moment. Indeed … war is more likely than not.”

The methodology his team uses is about as rigorous as you can get in such analyses, which is to say not rigorous at all, but you can’t reasonably expect historical analysis to be rigorous in the manner of the hard sciences. (This is a point he’s careful fully to concede, to his credit.)

They’ve taken 16 case studies from the past 500 years, and they’ve used the words “rise” and “rule” according to their “conventional definitions,” which is to say, “generally emphasizing rapid shifts in relative GDP and military strength.” In 12 of these 16 cases, he notes, the result was war. (I would quibble with the word “result” — it suggests causation where in fact what we’ve established is correlation — but that’s a quibble.)

Here’s the graph:

So I’m trying to figure out why he’s wrong, because clearly, I don’t relish the idea of war with China. First thing I noticed — this jumped out at me at first glance — is that the analysis is predicated on the idea that the nuclear era is relevantly similar to the pre-nuclear era. As you can see, it’s only before the mid-20th century that the inevitable outcome of such a power shift — with one notable exception — was “war.” (I might even make the argument that the UK and the United States were, for all intents and purposes, the same power, so we could almost go with “without exception,” but maybe that’s stretching it.) Following the development of the atomic bomb, however, 100 percent of these power shifts end in “no war.”

Of course, when your data set comprises a mere three examples, “100 percent” isn’t as reassuring as you’d like, but still, that’s reassuring — isn’t it? Sort of?

The more complex question I’d ask about this data set is whether it makes sense to choose these case studies. For example, you could credibly argue that by the 16th century, the Ottoman Empire was already on the decline and the Hapsburgs were the rising power, if we’re going by the “conventional definitions” of relative economic and military strength. What’s more, the “conventional definition” is retrospectively imposed. The definition at the time was proven — by the outcome — to be wrong. (After all, the Hapsburgs won. By this point, we’re well into Ottoman corruption and decline; or at the very least, we’re well into lousy drill, inferior order, inefficient supply lines, lower-quality weapons, and comparatively undeveloped finance, bureaucracy, and scientific patronage — not to mention constant hassle from the Safavids and the Mamluks — so frankly, they never stood a chance; but the only way to know that is in retrospect. They certainly seemed terrifying at the time.)

That said, though I can see a few methodological problems with his analysis, he’s making too many good points for me to write it off. So I’m not inclined to shrug. And as he points out, neither are many other people who’ve exhibited a certain amount of geopolitical common sense over the years:

The preeminent geostrategic challenge of this era is not violent Islamic extremists or a resurgent Russia. It is the impact that China’s ascendance will have on the U.S.-led international order, which has provided unprecedented great-power peace and prosperity for the past 70 years. As Singapore’s late leader, Lee Kuan Yew, observed, “the size of China’s displacement of the world balance is such that the world must find a new balance. It is not possible to pretend that this is just another big player. This is the biggest player in the history of the world.” Everyone knows about the rise of China. Few of us realize its magnitude. Never before in history has a nation risen so far, so fast, on so many dimensions of power. To paraphrase former Czech President Vaclav Havel, all this has happened so rapidly that we have not yet had time to be astonished.

He notes that his students are consistently flabbergasted when he asks them this question: “In what year could China overtake the United States to become, say, the largest economy in the world, or primary engine of global growth, or biggest market for luxury goods?” He then gives them this quiz:

- Manufacturer:

- Exporter:

- Trading nation:

- Saver:

- Holder of U.S. debt:

- Foreign-direct-investment destination:

- Energy consumer:

- Oil importer:

- Carbon emitter:

- Steel producer:

- Auto market:

- Smartphone market:

- E-commerce market:

- Luxury-goods market:

- Internet user:

- Fastest supercomputer:

- Holder of foreign reserves:

- Source of initial public offerings:

- Primary engine of global growth:

- Economy:

(Pause for a moment and take it yourself, to see how you do. Then keep scrolling.)

Answer: China’s already surpassed the US on all of them. (By the way, how did you do? I got 16 out of 20. I thought I was right and he was wrong about the four I missed, but I looked them up, and nope — he’s right. Bonus: Who’s number two on FDI? Did anyone here get that right without looking?)

Take twenty minutes and read the whole article. He makes some very sobering points, and I can’t really find a way to argue with most of them, except to say, “Yes, but that was before the nuclear era.”

He concludes:

What strategists need most at the moment is not a new strategy, but a long pause for reflection. If the tectonic shift caused by China’s rise poses a challenge of genuinely Thucydidean proportions, declarations about “rebalancing,” or revitalizing “engage and hedge,” or presidential hopefuls’ calls for more “muscular” or “robust” variants of the same, amount to little more than aspirin treating cancer. Future historians will compare such assertions to the reveries of British, German, and Russian leaders as they sleepwalked into 1914.

The rise of a 5,000-year-old civilization with 1.3 billion people is not a problem to be fixed. It is a condition—a chronic condition that will have to be managed over a generation. Success will require not just a new slogan, more frequent summits of presidents, and additional meetings of departmental working groups. Managing this relationship without war will demand sustained attention, week by week, at the highest level in both countries. It will entail a depth of mutual understanding not seen since the Henry Kissinger-Zhou Enlai conversations in the 1970s. Most significantly, it will mean more radical changes in attitudes and actions, by leaders and publics alike, than anyone has yet imagined.

He doesn’t specify what kind of radical change or action, unfortunately. So here are the questions I’m left with:

1) Do you think he’s wrong? If so, why?

2) Are the case studies he’s choosing really relevantly similar?

3) If he’s right, what on earth should we do?

Published in General

All this is designed to deter war. The Chinese need to understand in their bone marrow that we could kick their a__ and leave them in total disrepair. If we don’t, we really risk war. China is very vulnerable in a number of ways (importing all manner of raw materials, especially fuels, segmented politically into regions, poor disenfranchised western rural areas, persecuted Muslim minorities, banking system a house of cards, etc..) The temptation to go to war to defuse some of these crises is real; the only prophylactic for this delusion is absolute US preeminence on the battlefield. This is where we should concentrate – like with the ‘Pivot to the Pacific’.

Let the Shiites and Alawites grind down ISIS.

Lepanto didn’t change the balance of power at all, although the Ottomans lost some good commanders (who were as irreplaceable as any good commanders). The arsenal rebuilt the fleet in short order, and things continued pretty much as before. What was very significant on the European side (which is why historians tend to overrate it) is that Lepanto was widely celebrated and had a huge (legitimate) propaganda function, which was These Guys Can Be Beaten.

The Ottomans hadn’t won every battle (e.g., they’d abandoned the troops at Otranto when Mehmed II died, got rained out of Vienna in 1529), but the perception was that they were basically unbeatable. And possibly Providentially so (remember Luther’s formulation that the pope was the soul of Antichrist and the Turk his body, the “scourge of God,” etc.).

However, when the Christian fleet won a clear victory by force of arms, it was: “ring bells, thank God, celebrate, maybe these guys aren’t twelve feet tall and our inevitable future overlords” (which Luther, again, among others used to contemplate very seriously—Luther generally thought it’d be an improvement over the Habsburgs as the Ottomans would leave their souls alone).

But Lepanto wasn’t the Battle of Midway by any means.

Yes, I got that, and also that clearly the argument was proved wrong. Twice.

However:

Was the world economy then as intertwined as the world economy today?

I don’t have an answer – just that it’s a lot more intertwined (20% of total GDP vs > 50% of total GDP dependent on imports/exports), and that may mean that we’ve passed a tipping point wrt what is and is not feasible.

And the substance of the economy has also changed – the things that can be physically conquered (oil fields, fertile plains) are relatively less important now than they were then.

And what were they beaten with? Venetian merchant ships with high cannon superstructures sent in front of the armada to pound the Ottoman fleet as it tried to sweep around them.

And even though they restored their fleet, they suffered a crippling loss of manpower — particularly harmful for galley warfare. The technological advance in warship design was indeed important: The Venetian galeasses were a real technological innovation, a major contributory factor in the Ottoman defeat. By this point, Western galleys had a significant tactical edge in a formal, head-on clash— greater weight of men and metal; raised fighting platforms; the musketeers and swivel gunners atop the arrumbadas raining fire onto the lower Ottoman decks; and protected from Muslim archery by wood and cordage ramparts. No explosed planks.

The Ottomans didn’t stand a chance, especially against a competent commander. Any partial engagement would have tilted toward the heavier Christian galleys so long as they held formation. It was all or nothing. Müezzinzade Ali Pasha would have needed a full, frontal clash —but even competently-handled flanking squadrons could handily frustrate an attempt by anything more than the odd galiot.

No, they hadn’t a chance. By that point, the Habs were just able to build more bang for the buck.

It was written.

]

How do you know so much stuff????

The problem with this is illustrated by a parallel argument that’s been mounted. Beginning with the first part of the 20th Century war that built into a world war, wars were supposed to be fought with the men and equipment in place at the time, one of the reasons for the emphasis on mobilizing to the frontier as fast as possible. The war would be fought so quickly and be over so fast reinforcements and combat loss replacements wouldn’t make to the fight. The German planner high command in the 19-zeros was so married to this idea that even though they’d got the arithmetic wrong on movements, and they knew they’d got the arithmetic wrong, they sent in the von Schlieffen Plan anyway.

Wars will be fought quickly and be over quickly. Except when they bog down.

Wars always have been too expensive to fight, and they always will be. They’ll still be fought, though, and in the end, the only one for whom the war will have been too expensive will be the one who lost. The one who surrenders rather than bear the cost of the fight will have paid an even higher price.

Eric Hines

It’s her seven-cat research staff….

Eric Hines

I love it when you talk naval tactics…

The argument that trade weaves us together making war unthinkable is not determining. However our interdependence under the gold standard prior to WWI was deep and real but also different. The governing class built from old landed wealth that had been the basis of power prior to the 19th century still mattered greatly even as new industrialists were richer, elbowing each other to join that class. Those old classes were hostile to commerce and to the industrialization that caused the rapid change in their fortunes. These sweeping changes gave rise to reactionary communists, socialists, Fabians in their class as well as stirring in them echoes of imperial greatness and clashing armies. They still have power, but now see security in bureaucratic inertia and peace, preserving old wealth from too much entrepreneurial dynamism. We aren’t them and should we choose, we can still lead and determine outcomes. But it doesn’t just happen, it’s not the human default position.

I am inclined say no. In addition to the cultural similarities between the U.S. and U.K. during the interwar era, there were also two dangerous, expansionist enemies that eventually compelled the U.S. and U.K. to set aside their differences: Nazi Germany and militarist Japan.

What emergent threat might cause the U.S. and China to undertake a similar course toward rapprochement today? ISIS? A resurgent Russian Federation? That does not appear likely.

This naval historian’s heart skipped a beat.

I don’t. But Bill and I share a keen interest in Ottoman history. His knowledge of it is much deeper than mine, however. So trust him on this one — although I have no idea what he’s going to say to that. But he will doubtless be right, as I’ll discover when I check the references.

Claire – I wanted to share this video by Andrew Shuen, Lion Rock Institute from PFS. What do you make of it?

Awesome video. Thanks!