Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

China and the Thucydides Trap

China and the Thucydides Trap

Graham Allison is probably best known to you as the author of Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis. I’ve always held him in high regard: He’s the old-fashioned, careful kind of political scientist (this as opposed to the new-fangled, addled-by-idiot-theory kind).

Graham Allison is probably best known to you as the author of Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis. I’ve always held him in high regard: He’s the old-fashioned, careful kind of political scientist (this as opposed to the new-fangled, addled-by-idiot-theory kind).

I just finished reading his very thoughtful and provocative article in The Atlantic, The Thucydides Trap: Are the U.S. and China Headed for War?

It’s very worth reading in full, but this is the gravamen:

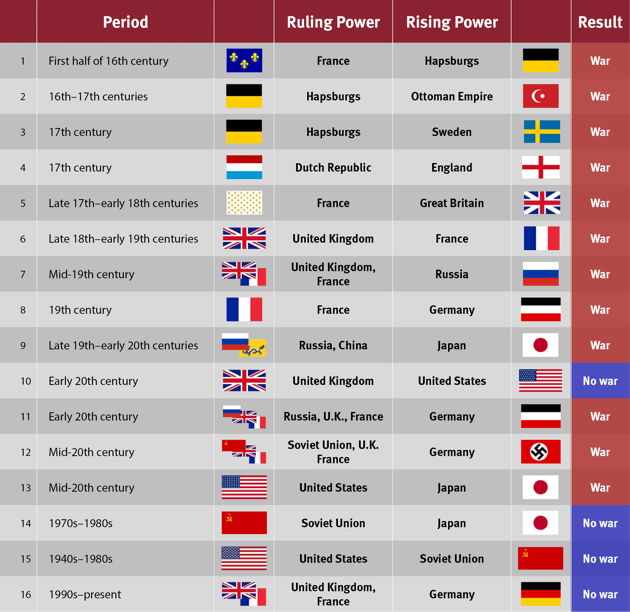

The Greek historian’s metaphor reminds us of the attendant dangers when a rising power rivals a ruling power—as Athens challenged Sparta in ancient Greece, or as Germany did Britain a century ago. Most such contests have ended badly, often for both nations, a team of mine at the Harvard Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs has concluded after analyzing the historical record. In 12 of 16 cases over the past 500 years, the result was war. When the parties avoided war, it required huge, painful adjustments in attitudes and actions on the part not just of the challenger but also the challenged.

Based on the current trajectory, he argues, “war between the United States and China in the decades ahead is not just possible, but much more likely than recognized at the moment. Indeed … war is more likely than not.”

The methodology his team uses is about as rigorous as you can get in such analyses, which is to say not rigorous at all, but you can’t reasonably expect historical analysis to be rigorous in the manner of the hard sciences. (This is a point he’s careful fully to concede, to his credit.)

They’ve taken 16 case studies from the past 500 years, and they’ve used the words “rise” and “rule” according to their “conventional definitions,” which is to say, “generally emphasizing rapid shifts in relative GDP and military strength.” In 12 of these 16 cases, he notes, the result was war. (I would quibble with the word “result” — it suggests causation where in fact what we’ve established is correlation — but that’s a quibble.)

Here’s the graph:

So I’m trying to figure out why he’s wrong, because clearly, I don’t relish the idea of war with China. First thing I noticed — this jumped out at me at first glance — is that the analysis is predicated on the idea that the nuclear era is relevantly similar to the pre-nuclear era. As you can see, it’s only before the mid-20th century that the inevitable outcome of such a power shift — with one notable exception — was “war.” (I might even make the argument that the UK and the United States were, for all intents and purposes, the same power, so we could almost go with “without exception,” but maybe that’s stretching it.) Following the development of the atomic bomb, however, 100 percent of these power shifts end in “no war.”

Of course, when your data set comprises a mere three examples, “100 percent” isn’t as reassuring as you’d like, but still, that’s reassuring — isn’t it? Sort of?

The more complex question I’d ask about this data set is whether it makes sense to choose these case studies. For example, you could credibly argue that by the 16th century, the Ottoman Empire was already on the decline and the Hapsburgs were the rising power, if we’re going by the “conventional definitions” of relative economic and military strength. What’s more, the “conventional definition” is retrospectively imposed. The definition at the time was proven — by the outcome — to be wrong. (After all, the Hapsburgs won. By this point, we’re well into Ottoman corruption and decline; or at the very least, we’re well into lousy drill, inferior order, inefficient supply lines, lower-quality weapons, and comparatively undeveloped finance, bureaucracy, and scientific patronage — not to mention constant hassle from the Safavids and the Mamluks — so frankly, they never stood a chance; but the only way to know that is in retrospect. They certainly seemed terrifying at the time.)

That said, though I can see a few methodological problems with his analysis, he’s making too many good points for me to write it off. So I’m not inclined to shrug. And as he points out, neither are many other people who’ve exhibited a certain amount of geopolitical common sense over the years:

The preeminent geostrategic challenge of this era is not violent Islamic extremists or a resurgent Russia. It is the impact that China’s ascendance will have on the U.S.-led international order, which has provided unprecedented great-power peace and prosperity for the past 70 years. As Singapore’s late leader, Lee Kuan Yew, observed, “the size of China’s displacement of the world balance is such that the world must find a new balance. It is not possible to pretend that this is just another big player. This is the biggest player in the history of the world.” Everyone knows about the rise of China. Few of us realize its magnitude. Never before in history has a nation risen so far, so fast, on so many dimensions of power. To paraphrase former Czech President Vaclav Havel, all this has happened so rapidly that we have not yet had time to be astonished.

He notes that his students are consistently flabbergasted when he asks them this question: “In what year could China overtake the United States to become, say, the largest economy in the world, or primary engine of global growth, or biggest market for luxury goods?” He then gives them this quiz:

- Manufacturer:

- Exporter:

- Trading nation:

- Saver:

- Holder of U.S. debt:

- Foreign-direct-investment destination:

- Energy consumer:

- Oil importer:

- Carbon emitter:

- Steel producer:

- Auto market:

- Smartphone market:

- E-commerce market:

- Luxury-goods market:

- Internet user:

- Fastest supercomputer:

- Holder of foreign reserves:

- Source of initial public offerings:

- Primary engine of global growth:

- Economy:

(Pause for a moment and take it yourself, to see how you do. Then keep scrolling.)

Answer: China’s already surpassed the US on all of them. (By the way, how did you do? I got 16 out of 20. I thought I was right and he was wrong about the four I missed, but I looked them up, and nope — he’s right. Bonus: Who’s number two on FDI? Did anyone here get that right without looking?)

Take twenty minutes and read the whole article. He makes some very sobering points, and I can’t really find a way to argue with most of them, except to say, “Yes, but that was before the nuclear era.”

He concludes:

What strategists need most at the moment is not a new strategy, but a long pause for reflection. If the tectonic shift caused by China’s rise poses a challenge of genuinely Thucydidean proportions, declarations about “rebalancing,” or revitalizing “engage and hedge,” or presidential hopefuls’ calls for more “muscular” or “robust” variants of the same, amount to little more than aspirin treating cancer. Future historians will compare such assertions to the reveries of British, German, and Russian leaders as they sleepwalked into 1914.

The rise of a 5,000-year-old civilization with 1.3 billion people is not a problem to be fixed. It is a condition—a chronic condition that will have to be managed over a generation. Success will require not just a new slogan, more frequent summits of presidents, and additional meetings of departmental working groups. Managing this relationship without war will demand sustained attention, week by week, at the highest level in both countries. It will entail a depth of mutual understanding not seen since the Henry Kissinger-Zhou Enlai conversations in the 1970s. Most significantly, it will mean more radical changes in attitudes and actions, by leaders and publics alike, than anyone has yet imagined.

He doesn’t specify what kind of radical change or action, unfortunately. So here are the questions I’m left with:

1) Do you think he’s wrong? If so, why?

2) Are the case studies he’s choosing really relevantly similar?

3) If he’s right, what on earth should we do?

Published in General

As for nuclear war, I have only encountered people who think it unwinnable among Americans. Maybe it is an admirable quality there cause liberalism to come to this conclusion, but Soviets were not liberals.

If we are not prudent and maintain the correlation in forces greatly in our favor, we could very well pay dearly down the road. Time to be proactive, no matter our fiscal limitations. Let Europeans pay for more of NATO’s upkeep. Russia is disappearing in ten years (says Zeihan) – let Nature do its work on that side of the world. And follow the Reagan doctrine of supporting Sunni and Shia fratricide. Let the worm Ouroboros swallow its own tail.

PS. Can anyone translate for me?

This is a great concern. Mao was extremely bellicose (something Khrushchev found repellent), constantly agitating for the USSR to start a general war. I see the same strain of thought in many of China’s generals, who seem willing to risk a war on the grounds that China would survive out of sheer numbers, while the US would be incinerated. That’s a frightening calculus – the notion that you would be willing to seriously wound yourself if it meant exterminating your enemies.

He is completely wrong, starting with the idea that China is a “rising power”. It rose but now it has peaked and will level off or decline. There was a window of opportunity to introduce political reform and get a shot at number one. But the ruling party did not seize on it. Too bad.

When you ask the question “In what year could China overtake the United States?”, the only interesting variable is total wealth creation. And on that, they are not even close.

What they are doing in Latin America is small change to what they are doing in Africa, where the risk is calculated to be minimal – after all, only the USA or Europe could challenge them there and that won’t happen as it would be immediately seen as Neo Colonialism. China wants to lock down Africa’s resources, not settle people there or trade with Africa. For China, this is not seen as a burden, just strategic business.

And in the long run it’s probable that he was correct, right?

The difference between then and now might be:

.

The European Union’s central achievement was that Germany and France will never go to war with each other again. (Good thing, after two world wars.) That happened because of deepening trade – so clearly even the cheek by jowl countries weren’t trading as much as they could have been before then.

The potential fly in the ointment is if China’s economy goes pear shaped and the regime there needs an ‘issue’ to stay in power. Imho that’s what managing China entails.

This is an old strain in American thought. Our own rhetoric in the 50s and 60s constantly harped that we were losing the missile race, the bomber race, etc. Cooler analysis (and some declassified US and Soviet documents) have since shown that we were constantly over estimating Soviet capabilities across the board. I have no idea whether this holds true vis. China, but I suspect there to be somewhat the same issue.

That, and Germany no longer lets nationalist loonies run the show. Does China? I suspect, as with 1920’s Japan, there is potentially a huge internal conflict brewing between the nationalists and everyone else. The internal power politics in China will be fascinating to watch.

Europe is not an actor in foreign affairs, it is a stage. Regime change is the only way to war. If you think of politics as holding empire, the question really is whether America will conquer Europe or not.

Did the US and USSR really think of nuclear war the same way with the same purpose?

Now, the European peace being the effect of trade. That is a vulgar opinion, which ignore s utterly the horrors that taught French and German to trade…

Or whether China will. Still parsing this article from today:

https://www.chathamhouse.org/publication/twt/chinas-inroads-west

Depends on who was in charge of the USSR. There is much evidence that Stalin was, at the time of death, gearing up to go to war with the US. Khrushchev was terrified at the prospect, though so erratic that he nearly caused such a war anyway. I’ve not read enough of Brezhnev to guess at his thoughts.

The only problem I see is that he’s looking over here instead of looking over there. If China and the US end up on opposite sides in a war it will probably be because Iran poked Saudi Arabia one too many times. Or the Supreme Leader’s janitor bumped the “DO BOMB SOUTH KOREA” button with his mop. It probably won’t be that we wanted to go to war with each other.

There’s tension in the network wires. Any wire can snap at any time. It may not be any of the wires that anyone is looking at right now.

Zeihan is interesting on this subject. He and George Friedman think the EU is going to fall apart soon. What then?

Also, Z thinks much of this statistic: only 15% US GDP is imported & 5% of that is oil, 5% NAFDA countries. So he predicts the middle number to drop to 0% and that the US will then leave the Bretton Woods framework where US defended everyone’s trade routes. We retire from the greater world (except to protect trade for Japan and SK) – and then what?

The Chinese government’s approach to a creating a real estate bubble is unique and hard to sustain.

When I read the column, I thought “well, I agree with the thrust of it,” as I’ve long worried about the U.S. and China blundering into a war in the Pacific, or China’s picking a fight with a Wilhelmine chip on her shoulder. But the one case on here with which I’m familiar—the Ottoman-Habsburg rivalry of the 16th and 17th centuries—is not easily characterized in the paradigm they’re talking about. Both powers basically achieve world-power scene at exactly the same time—Charles V’s inheritance and the Ottomans’ conquest of the Levant and Egypt.

Charles fortuitously inherits vast swaths of Europe (France being the major exception), and to pick a date at which he becomes a world leader, let’s say his being crowned Holy Roman Emperor in 1519. This is almost exactly contemporaneous with the Ottoman entrée onto the world stage.

The Ottomans were a large Balkan kingdom which acquired a very prestigious capital (Constantinople) in 1453 (and therewith a claim to Roman Imperial rule which they took very seriously). But it still was a regional power at best, and moreover, one whose possessions in Anatolia (what we think of as “Turkey”) were extremely insecure and tenuously ruled, and increasingly under the sway of chiliastic propaganda from the Safavid movement in northwest Persia and Azerbaijan.

The understudied reign of Selim I (1512–1520) is the point at which the Ottomans actually become a world power. He defeats the ascendant Safavids at Çaldıran in 1514, more or less defining the western border of what becomes Iran. In 1517, he destroys the Mamlûk state in Syria and Egypt. The Balkan kingdom is suddenly in possession of an actual empire.

Meanwhile in 1519, Cortés lands his expedition on the Mexican mainland, and what will become the Spanish Habsburg empire really gets rolling.

Selim dies suddenly in 1520, and his unprepossessing-seeming son Süleyman (r. 1520–1566) takes over, with advisors telling him he’s the Last World Emperor foretold in the Book of Daniel and the Joachimite school of history (somewhat Islamicated); which is exactly what Charles V’s advisors are telling him. Süleyman has the initial advantage of possessing two of the three major sites of Imperial and religious prestige (Constantinople and Jerusalem) and neither has Rome (until 1529 when to both of their horror, Charles’s unpaid Lutheran mercenaries sack the place). They proceed to more or less fight a world war over who was the Last World Emperor, until it becomes clear that neither can win.

Both leave rich and powerful states (Charles leaves two, as he decides the “German” and Spanish parts of the Empire have to be ruled separately) and both fight each other on and off the whole time, with the centuries bookended by sieges of Vienna in 1529 and 1683. By the end of Süleyman’s reign, the Ottomans rule from Budapest to Basra to the Maghrib. [Con’t.]

During the Korean War, Mao suggested a nuclear strategy to the Russians. He would entice the U.S. to pursue his army into China where he wanted the Russians to use nuclear weapons to destroy the U.S. army. The Russians were horrified and turned his request down.

Certainly. I just worry that China sees itself, in many ways, the same way Germany did in 1913 or 1938, or as Japan saw itself in 1933.

This is the key consideration in my mind. You have to look not just at latent powers but also at the will to use them and general priorities.

For example, the US has nukes, but every national leader knows we won’t use them. Modern American sensibilities won’t allow it. Likewise, modern American political culture is horrified by the prospect of conquest. So even when we occupy a nation like Iraq or Afghanistan, we turn a blind eye to child rape, anti-Semitic speeches by their politicians, and other evils. We wouldn’t dare impose our own values. And the American electorate is so wishy-washy on war that, even if our representatives overcome isolationist movements, we can’t maintain a winning strategy for more than a year or two.

I’m less concerned about China moving up in the world than about the US and Europe moving down by choice. Half of our society doesn’t want that power or influence anymore. And the other half can’t imagine anything other than self-defense to justify going to war with a truly major power.

[Con’t.]

And unlike the Ottoman polemicists of the late 16th century (and the western historians who perhaps naïvely followed them), I don’t think there’s a visible decline in Ottoman fortunes at all over the next century or so. There are critical changes in the system of governance (which get called “decline” by the losers in the political battles), but the Ottomans and the Habsburgs are much more like the post-war U.S. and U.S.S.R. in that you have two regional powers which simultaneously become global rivals. There’s not really a status-quo power and a revolutionary power. They both form a new status quo (the Cold War or the Ottoman-Habsburg rivalry which displaced the old Balkan tripartite rivalry of the Hungarians, Venetians, and Ottomans trying to fill the Byzantine power vacuum), which finds its equilibrium when they can’t defeat each other. Both had other concerns—the Safavids for the Ottomans (though they’re never a mortal threat), the French and the Protestants for the Habsburgs. The Habsburgs of course court the Safavids and the Ottomans and French become formal allies, so this proceeds in pretty comprehensible terms.

Anyway, this may all be nitpickery, but I’m a little leery of enlisting these two players into a “ruling power vs. rising power” framework. Both empires came into being fairly quickly and more or less simultaneously in two separate, highly fragmented milieux.

Someone will take your place (eventually). Nobody is irreplaceable.

And how much of US GDP is due to exports? At the end of the day maintaining trade routes is in the US’ self interest, it isn’t an act of altruism.

(Or perhaps one should say, it is in the interest of enough US interests who have influence over US foreign policy.)

Quick notes.

American moralism is, if I understand you correctly, insufficiently worried about anti Semitic speeches in Afghanistan?

So Mao is supposed to have told Khrushchev about nuclear war, who is supposed to have replied, the problem with the atom bomb is, it does not let the principles of the class struggle. There’s a lesson in there somewhere about the random between convention and necessity, it the tension within striving…

Good questions. Since we have a net trade imbalance it is less than the 15% GDP for imports (looked it up = 13.5%). If we export oil and LNG, this number can grow appreciably, but we will need to guarantee only the relevant trade corridors, which may just be to SK and Japan and maybe the EU (and hopefully China as well), all distant from the Gulf region.

So not sure we would feel compelled to be the world trade route cop after these changes occur (specifically deleting all oil imports from Mideast). This is Zeihan’s conclusion at least.

PS. Canada and Mexico account for over 1/3 of that 13.5% export GDP figure.

Not exactly. The way Khrushchev described it in his memoirs, in his meetings with Mao, Mao was constantly egging the USSR on to start a nuclear exchange, claiming that both China and the USSR would rise from the ashes. Khrushchev, having survived Stalin and The Great Patriotic War, viewed Mao as another Stalin, all too willing to butcher millions just to cement his own power, and moreover he suspected that Mao really wanted the USSR wiped out so that China could run the communist world. In the Party Congress of 1961, Mao openly attacked Khrushchev for being soft and weak for not actually wanting a great purging war. Mao’s belligerence frankly astonished the Soviets.

I want to start with a couple of disagreements re the information discussed in Claire’s post.

Most importantly, I do not agree that China is the world’s largest economy, nor that it is the primary engine of global growth.

Using nominal exchange rates, which is the more relevant measure for this purpose, China’s GDP is about $10.4 trillion compared to about $17.4 trillion for the US. China has a slightly higher GDP using the PPP (purchasing power parity) method, but this approach is not really suited to comparing national economies. PPP is better suited to comparing the well-being of individuals or smaller sub-national groups.

China appears to be following the path of Japan and South Korea, basing its economic growth on exports, especially to the US. There is a natural limit to such growth, because as Chinese living standards and wages rise, there will be enormous economic pressure to shift manufacturing to lower-wage countries like India. The “engine” of world economic growth remains the US, with China prospering through its access to the US market.

Define “war.” We certainly were in a 40-year war with the USSR; the Cold War just didn’t involve shooting directly at each other. Except for the odd USA Major murdered by the Soviets in East Germany (occupied Germany, as many of my Luftwaffe counterparts termed it). It most certainly was a direct confrontation politically, economically, socially, morally, and any other -lly you might think of. That war also ended with a fairly significant power shift.

For another take on the potential for the inevitability of war with the PRC (my conceit: I use that to distinguish it from the other China, the RoC), may I suggest Michael Pillsbury’s The Hundred-Year Marathon? If he’s right, the inevitibility isn’t there, if we play our part as the existing hegemon against Xi’s and his cohort’s (it’s the men, not the nation, with whom we’re contesting, after all) rising hegemon. They’re trapped in their country’s Warring States period and using the political, economic, military, and dissemination techniques from that period to good effect. Their behavior over the last few years is consistent with that thesis. With their seizure of the East and South China Seas, they’ve reached a stage where they think it’s useful to ask us the status of our cauldrons.

That’s my answer to your first question. The answer to your third is straightforward, if Pillsbury is right. It’s also the answer even if Pillsbury is wrong. Military confrontation will push them back. It doesn’t even have to be actual shooting; credible demonstrations (and given the level of damage Obama has done our prestige, our reputation, our actual power, it will take more than one) will serve. Most likely. It’ll also take a major buildup of our naval and air forces, both in numbers and in technology.

A couple of asides of more or less relevance. Kissinger came away from those meetings with exactly zero understanding of Zhou or of the PRC or of the people on the mainland. Just some happy talk that moved the cauldron down the hall a bit.

A 5,000 year history isn’t relevant. The PRC (and us) have the political, economic, and military mass we have today, with today’s development and deployment momentum for tomorrow, and only that.

Straight up nuclear war, of the kind the US and the PRC might fight isn’t all that. Missile defenses put those into a cocked hat. Those warheads that get through will do considerable damage, but even if all of them got through, it won’t represent The End of Civilization. Nuclear winter is brought to you by the same class of panic-mongers as climatologists. Besides, precision weapons do the same job far more cheaply, and a well done cyber war would be far more devastating (along those lines, let me recommend Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui’s Unrestricted Warfare. It might seem apocalyptic, but…).

Eric Hines