Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Just Because Hillary Clinton Thinks Corporate ‘Short-Termerism’ Is a Problem Doesn’t Mean it Isn’t

Just Because Hillary Clinton Thinks Corporate ‘Short-Termerism’ Is a Problem Doesn’t Mean it Isn’t

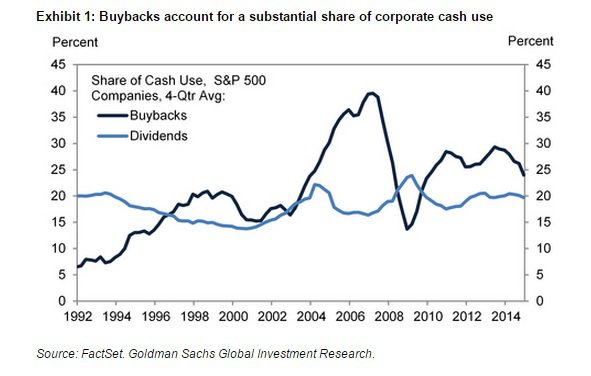

The FT’s Ed Luce takes a look at the “quarterly capitalism” or “short-termism” issue, concluding that it has merit as well as political legs. He points out that “US investment is at its lowest since 1947″ but that last year “S&P 500 companies spent more than $500bn on share buybacks.” He doesn’t, however, think further raising the capital gains tax rate for short-term investment is an effective solution — as Hillary Clinton wants to do — versus reforming executive pay:

It is doubtful such tinkering would be enough to alter investors’ time horizons. The lure of a bird in the hand would still outweigh two in the bush. Many big investors, including pension funds, are already exempt from taxation. Nor is [Clinton’s] proposal likely to deter shareholder activists, whose gains from holding C-suites to ransom will outweigh any new penalties. As long as chief executives’ compensation packages are set by the share price, little is likely to change.

I am more positive that, at the margin, tax reform can help — as I recently told Ben White of Politico. But generally experts who have proposed similar plans would also deeply cut cap gains rates the longer an investment is held, maybe even to zero for investments held 5 to 8 years or so. Clinton’s approach would raise the ceiling but not the the floor. Of course, cutting taxes for wealthier Americans is anathema to Democrats so she is forced to offer a bizarre version of what could be a pretty good idea.

Now Tyler Cowen questions whether short-termism is really even a thing and cites a couple of studies. I would add to the debate with a new paper, “The Macro Impact of Short-Termism” by Stephen Terry of Boston University, which concludes that short-termism from investor pressure “distorts long-term investments and imposes costs on firms and the broader economy” although “the presence of discipline may provide benefits if managers are motivated by agency considerations such as a desire to shirk or to empire build.”

Also in the FT, McKinsey’s Dominic Barton and Mark Wiseman of the Canadian Pension Plan Investment Board note research that has found “privately held companies, free to take a longer-term approach, invest at almost 2.5 times the rate of publicly held counterparts in the same industries. This persistent lower investment rate among America’s biggest 350 listed companies may be reducing US growth by an additional 0.2 percentage points a year.” I sure would love to see more research on this subject.

Then there is this interesting bit from an Economist story on Silicon Valley on why more startups are staying private longer:

It used to be extremely rare to find a startup valued over $1 billion, but today there are 74 such “unicorns” in America’s tech sector, valued at $273 billion. That is 61% of all the unicorns in the world by number, according to CB Insights, which tracks the private market. Many entrepreneurs view life as a public company, with its quarterly appraisals and activist shareholders, as akin to being the giant effigy at the focus of the annual “Burning Man” gathering in the Nevada desert: yes, you may be quickly built into the biggest thing around, but the experience promises more than a little pain. And drumming up capital without the help of the public markets is unprecedentedly easy. In the face of low interest rates, investors have scrambled to find any sort of yield. Mutual funds such as Fidelity and T. Rowe Price are investing in unicorns in late-stage rounds, as are hedge funds, sovereign-wealth funds and large firms.

Of course, maybe voters would take the issue more seriously if the politicians talking about it were also attacking short-termism in government, which is a far worse problem.

Published in Economics

The piece, “Short Term versus Long Term”, July 27, in the Future of Capitalism blog captures the issue pretty well. www.futureofcapitalism.com/

There is a short term mentality in most business because that is exactly the mindset of our Society right now: politically, economically, culturally, socially and globally.

Also, if you believe the Peter Thiel theme that innovation will be truly dead and stat ism will become the norm when the Government regulates not only the “atom” but also the “byte”. (My translation of his theme, no disrespect to Mr. Thiel). With the recent FCC action, we now have both. What business is going to invest in the future when any large investment may ultimately bring about the enterprise’s demise?Better to cash out and ride out the coming economic debacle that Jeremy Grantham sees coming after the 2016 election. If he is right we may wish for a Dem in the WH to take the heat.

The problem with technocrats is that the conversation always begins and ends with the same question: “What can we do to interfere in ________ ?”

Excuse me, but what part of “freedom” don’t you understand?

What if the long-term rate of return from buying one’s own stock is simply greater than the long-term rate of return from other forms of investment? I fail to see how buying one’s own stock is, in and of itself, evidence that a corporation is not thinking about the long term.

The whole “short-termism” argument is little more than an attempt to shift the blame for America’s slow growth away from Obama’s anti-business policies and onto the backs of CEOs.

The “short-termism” idea implies that there are lots of long-term investment opportunities out there that business leaders are ignoring. Companies that ignore such opportunities don’t stay solvent for long.

Business aren’t investing because they see lots of risks and little reward. A basic principle of economics is that people respond to incentives.

Even if it is a problem, why is it the government’s job to sort it out? Huh? Huh? Answer me that!

Strangely enough, when regime risk is added to long term investment risk, short term investing becomes the tune of the day. “Bad luck”, as they say.

Good point. It also seems to me that corporate preference for stock buy-backs, rather than distributing cash as dividends, is probably driven by existing (perverse) tax incentives — i.e. by the fact that a stock buy-back might get preferential tax treatment as a capital gain, while a dividend is generally taxed as ordinary income.

I find this type of analysis dubious, though I don’t have time to dig into it thoroughly. It comes across as cherry-picking, especially in the choice of the “biggest 350 listed” companies. Why 350? The typical measure is the S&P 500 — which is used in the OP’s main chart. When researchers depart from using the usual metrics, it leads me to suspect that, if they did, their result wouldn’t hold up.

It’s also not surprising at all that generally larger, publicly-held companies invest at a lower rate than generally smaller, privately-held companies. Which do you think are typically startups, characterized by high (and often very risky) investment. Those that succeed tend to either become publicly-traded, or be bought by a publicly-traded company. These facts don’t suggest any particular problem to me.

Isn’t this just another way of saying the discount rate is too high on available projects?

Publicly traded companies are not the job creators in the country. For the most part they try to appeal to both the gamblers(traders) in the mark and the investors. Since senior executives are in large part compensated on stock price they naturally tilt toward the traders.

Thinking that any tax plan based on the taxing of publicly traded stocks would make any manful difference in workers compensation or job creation stupid.

It’s not obvious what interference would do to remedy the problem. It’s part of public ownership of shares, seems to me. Nonetheless, I would like to know if oil majors are an exception. I keep hearing of so many very long-term investments made by oil majors. Family controlled companies may be another exception.

I say that all the time, and people just roll their eyes.

If it’s government action that caused the problem in the first place, then yes, it is the government’s job to sort it out … by removing the impediment that caused the problem.