Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

We Must Continue the Debate Over Torture

We Must Continue the Debate Over Torture

In the modern world of ever changing events, nothing — no matter how important — can long survive the shifting sands of something new. I don’t know which story pushed torture over the cliff. It might have been Charlie Hebdo. It might have been the opening of the new Congress. Perhaps it was simply that our heads were swimming in the Tsunami of ISIS and politics and the Holidays. But the debate should continue, and the arguments — pro and con — should still flood the airwaves and pepper the newspapers. That, I am sad to say, isn’t happen.

In the modern world of ever changing events, nothing — no matter how important — can long survive the shifting sands of something new. I don’t know which story pushed torture over the cliff. It might have been Charlie Hebdo. It might have been the opening of the new Congress. Perhaps it was simply that our heads were swimming in the Tsunami of ISIS and politics and the Holidays. But the debate should continue, and the arguments — pro and con — should still flood the airwaves and pepper the newspapers. That, I am sad to say, isn’t happen.

On Frontline last week, PBS took up the subject and focused attention on the failures of Enhanced Interrogation Techniques (EITs). Writing for The American Conservative, Kelly Thomas complains that the obsession with success has preempted the larger moral issues over the use of torture (or EIT). Thomas notes:

The persistent focus on torture’s ineffectiveness, however, naturally leads to the question: if they had worked, would we be bothered? If EITs had been as effective as Soufan’s more moderate techniques, would anyone be upset by the suffering of a few dozen violent extremists? The documentary leaves the impression that the most repulsive element of the CIA’s brutality was that it was all done in vain rendering former acting CIA Director John McLaughlin’s justifying comment, “We were at war. Bad things happen at war,” utterly indefensible.

Thomas makes an enormously important point. The moral question has been set aside, or at best left only implied. When normative ethics are swept aside, and all that matters is efficacy, we have consequentialism of the purest kind.

Purest, and also of the worst kind.

Just after the Senate Intelligence Committee Report on interrogation tactics came out I posted a piece in which I rabidly defended the CIA. Ricochet editor Tom Meyer replied with a thoughtful article challenging my many assumptions. Tom’s point (I think I am accurately representing him) was that while some circumstances might justify torture, e.g., the “ticking time bomb scenario,” the ends do not justify the means in every case. That, I now see, is correct, both morally and practically. I credit Tom for reminding me that an issue as profound as torture demands careful thought. Frontline’s analysis of the success or failure of the Enhanced Interrogation Technique program does make clear that — for the most part — beating information out of a prisoner rarely results in useful intelligence. Having independently researched the question, I now have strong reasons for the conclusion that EIT s are usually fool’s errand (more on that at some later date).

However, the real question is not whether the end justifies the means, but whether the end justifies any means. There are some means that are intrinsically evil no matter whether something positive comes out of them or not. If murder is “the deliberate taking of an innocent human life,” then murder can never be justified–not even if a thousand lives are saved.

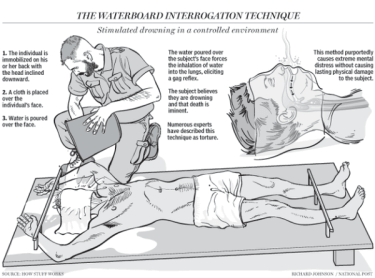

Which leads to the question: can waterboarding, sleep deprivation, or force feeding ever be properly used to secure information about an enemy’s intentions? In Thomas’ view, this is at the heart of the matter:

But what if it had indeed been torture that had led to Osama bin Laden’s death, as the movie “Zero Dark Thirty” actively sought to depict? Would the U.S. be less morally culpable for the acute suffering it inflicted upon unarmed and defenseless men if American lives truly had been saved as a result? The CIA thought that the public would be largely appeased by the supposed effectiveness of the torture in “Zero Dark Thirty,” so the answer seems to be a deeply disturbing “yes.” We, alongside our leaders, appear to be comfortable with torture as long as it gets the job done.

The implications of this utter disregard for morality are horrifying. If efficacy and efficiency—rather than morality—become the governing ethical considerations in war, then what of the ideals the U.S. is purportedly fighting for?

This question demands that we move beyond utility and examine the issue in the light of higher principles. When utility is the sole guiding light, what happens to the heart of the nation? What will be the long-term effects of substituting “it works” for “what is morally permissible?”

To properly address the issues means developing a moral theory upon which we can rely when a new crisis emerges, as it surely will. One place to start is with the United Nation’s Convention Against Torture which provides

Having regard to article 5 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and article 7 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, both of which provide that no one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment…

Torture is defined as:

…any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession…

The UN is notoriously inconsistent in applying the rule. Still, both the definition and the prohibition have the advantage of clarity. If torture is prohibited, there are no circumstances, no matter how urgent, and no matter how great the harm that might ensue, that can justify its use.

My apodictic defense of EITs in the earlier post made passing reference to the basic moral principle that when confronted with ambiguous moral questions we must take the morally safer course. Nonetheless, I offered little in the way of moral nuance. Moral questions, however, must not be decided on emotional reactions, but on careful analytics, and with an acute awareness that some moral truths can never be set aside.

My simple suggestion is that we take the UN definition as a jumping off point. The most effective approach to important questions is to start at each end of the extremes, i.e., “torture never” versus “torture whenever,” and try to work towards something in the middle. This is a form of negotiation, and as with all negotiations, the best settlement is that which leaves each party a bit dissatisfied.

We must renew the debate, and soon, for this is an issue that will simmer below the surface—until something terrible cracks the crust.

Published in General

Are you saying there are no ill effects to the intentional infliction of very great or intense pain?

I think what you are trying to do is force an effective technique into a definition of torture that the evidence suggests it does not.

Are you willing to prosecute all the commanders who have overseen the waterboarding of US servicemen? If not, why not?

The effectiveness of a technique really has no bearing on whether or not its torture. The evidence you speak of is far murkier and less clear than you are allowing – hence the debate.

As I said – I do not know if waterboarding is torture, having never been through the processes as applied to our detainees (which, despite protestations in these comments was of a kind different in degree and duration to that which our soldiers are subjected). What I think is that the waterboarding is close enough to the line of torture that I am more ethically comfortable if we did not use this technique. Given that it has never been applied in a Jack Bauer style ticking time bomb scenario – I do not think it can be justified.

As for the commanders being prosecuted – they oversaw those actions under a legal framework where these techniques were not defined as torture, hence I would not prosecute. The OP asked about the issue in terms of higher principles – this is quite separate from legality.

Do you think that prison is dehumanizing to both guards and inmates?

Medium term sleep deprivation is bad for you, but it’s less bad than extended periods of prison.

It’s partly about cognitive load; fear isn’t painful, but it is distracting, and it fills you with adrenaline and endorphins. It’s also exhausting. You can get a lot more out of interrogations if you can get people to work out while you’re interrogating them, for instance.

The severe mental pain was a reference, as I understand it, to mock executions or to threats to harm others, which is different from a pure simulation of fear. Waterboarding, like a roller coaster, isn’t about mental pain, even though some of the synapses used are the same. Obviously, the lizard brain response to waterboarding is considerably more intense than its response to roller coasters, but it’s the same essential concept; persuading the emotional parts of your brain that you’re in a life threatening situation.

That is surprising. I’m a lot more equanimous after, say, lifting weights. The positive mental effect lasts for hours.

As I said – I do not know if waterboarding is torture, having never been through the processes as applied to our detainees (which, despite protestations in these comments was of a kind different in degree and duration to that which our soldiers are subjected). What I think is that the waterboarding is close enough to the line of torture that I am more ethically comfortable if we did not use this technique. Given that it has never been applied in a Jack Bauer style ticking time bomb scenario – I do not think it can be justified.

What is your evidence to support your claim that the technique differed substantively between that done to the terrorists and that done to our servicemen?

So, you would be content not to have the information gained from KSM? Information every Director of Central Intelligence and Director of National Intelligence has said was vital to our understanding of how al Qaeda was structured and operated?

As for the commanders being prosecuted – they oversaw those actions under a legal framework where these techniques were not defined as torture, hence I would not prosecute. The OP asked about the issue in terms of higher principles – this is quite separate from legality.

As far as I know, commanders are still overseeing the water boarding of soldiers, sailors,mailmen, and Marines under their command. Are you morally comfortable with them being free to do so?

I’d like to point out — again — that personality damage from sleep deprivation was understood and specifically provided against by the Guantanamo crew. The psychological damage from sleep deprivation is effectively a null issue in this conversation unless we’ve got evidence that anyone suffered such permanent harm.

Right. The aim with having people work out isn’t to give the guy a bad time, it’s to increase the cognitive load until being effectively uncooperative becomes too hard. Obviously, working out is way less intense than waterboarding, but it’s the same principle as most of the techniques. Sleep deprivation works at the other end of the supply/ demand tension.

One thing which is quite fun for those sorts of interrogations is getting people to tell stories backwards. It’s really hard to lie when you’re doing that, but we don’t expect it to be. This means that a surprising number of people will accidentally tell the truth if you get them to do this. Waterboarding also works by giving the guy a bad time, but that’s only one of the levels at which it works, and possibly not the most important. Making you stupid and dramatically shortening your event horizon by pumping you full of adrenaline and doing interesting things is pretty powerful.

I think it’s telling that the link is to an American Conservative piece that complains that Zero Dark Thirty doesn’t have a cartoon villain doing the interrogation, because everyone knows that torture is exclusively engaged in by sadists. It’s precisely that sort of thing that is properly referred to by people who dispute the “American” part of the organ’s title as well as the “Conservative” part.

It’s true that engaging in interrogation is pretty awful; just ask Ryan M, or anyone else who has to deal with terrible people. This doesn’t mean that every prosecutor, or every prison guard, turns out to be an awful person. When your complaints about Hollywood are that they don’t draw a false moral equivalence with Saddam, there is something very deeply wrong with your sense of the world.

We were able to track down Bin Laden because we had human and technological intelligence. We could not possibly have watched hundreds of millions of Pakistanis by drone, even if we were able to narrow his location down to Pakistan and were then able to devote the working lives of every American to the task. We needed to be told that the courier was significant, and it was the post-waterboarding KSM who told us that (admittedly by trying to hide it, rather than telling us directly).

The example is atypical in that the stakes are uniquely high in both directions (KSM was interrogated uniquely intensively, and OBL was a uniquely high profile target), but the same principles apply at every level. There’s just no substitute for actual, in person, knowledge. Maybe if we get the ability to listen from the air, that would bring us closer.

Yes, the key to interrogation is to disrupt the narrative. Mental models of reality are highly interconnected; there are many approaches to truth. A false construct must be replayed as designed, else it fails.

There’s a lesson in this for dealing with liars in general, that is, the left.