Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

We Must Continue the Debate Over Torture

We Must Continue the Debate Over Torture

In the modern world of ever changing events, nothing — no matter how important — can long survive the shifting sands of something new. I don’t know which story pushed torture over the cliff. It might have been Charlie Hebdo. It might have been the opening of the new Congress. Perhaps it was simply that our heads were swimming in the Tsunami of ISIS and politics and the Holidays. But the debate should continue, and the arguments — pro and con — should still flood the airwaves and pepper the newspapers. That, I am sad to say, isn’t happen.

In the modern world of ever changing events, nothing — no matter how important — can long survive the shifting sands of something new. I don’t know which story pushed torture over the cliff. It might have been Charlie Hebdo. It might have been the opening of the new Congress. Perhaps it was simply that our heads were swimming in the Tsunami of ISIS and politics and the Holidays. But the debate should continue, and the arguments — pro and con — should still flood the airwaves and pepper the newspapers. That, I am sad to say, isn’t happen.

On Frontline last week, PBS took up the subject and focused attention on the failures of Enhanced Interrogation Techniques (EITs). Writing for The American Conservative, Kelly Thomas complains that the obsession with success has preempted the larger moral issues over the use of torture (or EIT). Thomas notes:

The persistent focus on torture’s ineffectiveness, however, naturally leads to the question: if they had worked, would we be bothered? If EITs had been as effective as Soufan’s more moderate techniques, would anyone be upset by the suffering of a few dozen violent extremists? The documentary leaves the impression that the most repulsive element of the CIA’s brutality was that it was all done in vain rendering former acting CIA Director John McLaughlin’s justifying comment, “We were at war. Bad things happen at war,” utterly indefensible.

Thomas makes an enormously important point. The moral question has been set aside, or at best left only implied. When normative ethics are swept aside, and all that matters is efficacy, we have consequentialism of the purest kind.

Purest, and also of the worst kind.

Just after the Senate Intelligence Committee Report on interrogation tactics came out I posted a piece in which I rabidly defended the CIA. Ricochet editor Tom Meyer replied with a thoughtful article challenging my many assumptions. Tom’s point (I think I am accurately representing him) was that while some circumstances might justify torture, e.g., the “ticking time bomb scenario,” the ends do not justify the means in every case. That, I now see, is correct, both morally and practically. I credit Tom for reminding me that an issue as profound as torture demands careful thought. Frontline’s analysis of the success or failure of the Enhanced Interrogation Technique program does make clear that — for the most part — beating information out of a prisoner rarely results in useful intelligence. Having independently researched the question, I now have strong reasons for the conclusion that EIT s are usually fool’s errand (more on that at some later date).

However, the real question is not whether the end justifies the means, but whether the end justifies any means. There are some means that are intrinsically evil no matter whether something positive comes out of them or not. If murder is “the deliberate taking of an innocent human life,” then murder can never be justified–not even if a thousand lives are saved.

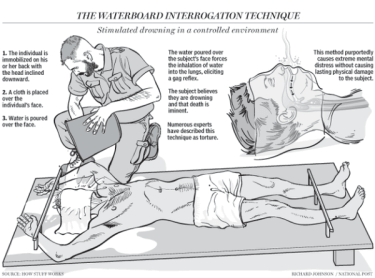

Which leads to the question: can waterboarding, sleep deprivation, or force feeding ever be properly used to secure information about an enemy’s intentions? In Thomas’ view, this is at the heart of the matter:

But what if it had indeed been torture that had led to Osama bin Laden’s death, as the movie “Zero Dark Thirty” actively sought to depict? Would the U.S. be less morally culpable for the acute suffering it inflicted upon unarmed and defenseless men if American lives truly had been saved as a result? The CIA thought that the public would be largely appeased by the supposed effectiveness of the torture in “Zero Dark Thirty,” so the answer seems to be a deeply disturbing “yes.” We, alongside our leaders, appear to be comfortable with torture as long as it gets the job done.

The implications of this utter disregard for morality are horrifying. If efficacy and efficiency—rather than morality—become the governing ethical considerations in war, then what of the ideals the U.S. is purportedly fighting for?

This question demands that we move beyond utility and examine the issue in the light of higher principles. When utility is the sole guiding light, what happens to the heart of the nation? What will be the long-term effects of substituting “it works” for “what is morally permissible?”

To properly address the issues means developing a moral theory upon which we can rely when a new crisis emerges, as it surely will. One place to start is with the United Nation’s Convention Against Torture which provides

Having regard to article 5 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and article 7 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, both of which provide that no one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment…

Torture is defined as:

…any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession…

The UN is notoriously inconsistent in applying the rule. Still, both the definition and the prohibition have the advantage of clarity. If torture is prohibited, there are no circumstances, no matter how urgent, and no matter how great the harm that might ensue, that can justify its use.

My apodictic defense of EITs in the earlier post made passing reference to the basic moral principle that when confronted with ambiguous moral questions we must take the morally safer course. Nonetheless, I offered little in the way of moral nuance. Moral questions, however, must not be decided on emotional reactions, but on careful analytics, and with an acute awareness that some moral truths can never be set aside.

My simple suggestion is that we take the UN definition as a jumping off point. The most effective approach to important questions is to start at each end of the extremes, i.e., “torture never” versus “torture whenever,” and try to work towards something in the middle. This is a form of negotiation, and as with all negotiations, the best settlement is that which leaves each party a bit dissatisfied.

We must renew the debate, and soon, for this is an issue that will simmer below the surface—until something terrible cracks the crust.

Published in General

iWe

Our country has decided it is nicer to kill people with missile strikes than to take them in and find out what they know. This is surely both worse for achieving our goals, and it is less moral. I would much rather be tortured and released than deprived of my life, and I suspect the vast majority of people feel similarly.

You’ve touched on the real paradox with the western obsession with enhanced interrogation. People shrug off drones killing suspected terrorists and even bystanders. But they are full of indignation about “torture”. But wouldn’t you rather be waterboarded than killed with a drone? And if we also know that the person being interrogated has the power to stop it at any time just by answering a question which they are 1)able to answer and 2)have the moral obligation to answer, wouldn’t that make the interrogation justifiable? So what is the source of the paradox? It can only be one of two things: western hedonism which views pain as the ultimate evil, or a moral vanity which is so hyperactive that it has no ability to distinguish between the relative “evils” of drone strikes and “torture”. Or both.

Which leads to the question: can waterboarding, sleep deprivation, or force feeding ever be properly used to secure information about an enemy’s intentions?

I take issue with the premise of this question, because as I understand it, EITs were not used to extract information, as in a 24 TV show scenario. They didn’t ask detainees questions they didn’t already know the answer to. You’re not going to get accurate info out of someone by beating it out of them. They know that, so let’s stop assuming that is the motive for EITs. Movies and TV are not real life. The EITs were designed for many aspects of intelligence gathering, including assessing the loyalty of the detainees to their cause and their rank within the insurgent hierarchy. If they can be incentivized to gather and relay information for us particularly if they are high-ranking, which I’m sure some did, it’s a program worth continuing. I think much is unknown to the public about what is involved in intelligence gathering and rightly so. Assessing the success or failure of the program is really kabuki theatre, because the CIA isn’t about to reveal the numbers of insurgents/terrorists turned informants.

A similar thing happened to none other than Alan West. He fired a pistol over the head of someone in custody to convince him he might be shot and his information saved the lives of American soldiers who were going to be ambushed. West was subsequently drummed out of the Army via court marshal for it. While I agree with Tom it may be the best “worst option” out there, it still sticks in my craw. War is hell, our enemy is fierce, the world is an icky business. I don’t think we should as a policy depend on honorable people’s willingness to destroy their careers and livelihood simply because we agree with their actions but aren’t willing to do so in public. Over time we may find that we have few honorable people in those positions anymore.

Waterboarding is torture.

You torture your own people as part of SERE training.

Deal with it.

We should not torture.

Torture is dehumanizing to both the user and the victim.

And your talking to someone who thinks the RAF bombing campaign was a good thing.

Sorry, you will get accurate info by beating it out of them. Torture works. It is effective. But just because it is effective doesnt mean you should do it.

There are lots of effective things out there that we dont do because they are morally wrong. Torture is one of them.

Well, this is a first for me. Using the United Nations as a starting point for a “morally nuanced” conversation. I would note that by the UN definition of “severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental,” my local DMV is engaged in torture on a daily basis. Using taxpayer funds, I might add.

My own starting point for a morally nuanced conversation is being able to see the difference between playing loud music to keep someone awake, and pulling out fingernails or chopping off limbs. If a person can’t tell the difference between those things, then I would urge them to stay away from the phrase “morally nuanced.” (Although if it was rap music, I might call it torture.)

I understand that this is your view, but saying back and forth “it’s torture” – “no it’s not” – “yes it is” — “deal with it” doesn’t help me in analyzing the difference in opinion.

I think that John Yoo’s EIT memos do help with this. As I recall, the dividing line under US law between “torture” and “non-torture” is whether is does actual, significant physical injury. Not pain, not fear, but actual injury. So keeping someone in a cold room, causing discomfort, would not be “torture” — but causing frostbite would be “torture.”

I submit that this at least helps us define terms. By this definition, as Yoo’s memos concluded, waterboarding is not torture.

I don’t agree with this, and I think that it’s incorrect under the UCMJ. I am not an expert in the area, but I have heard a couple of excellent lectures on the subject by experts.

First, if someone is a “combatant,” then both the UCMJ and international law allow our military to target him 24/7. It doesn’t matter if he is “helpless.” He can be asleep in bed, and our special forces can sneak into the room and shoot him in the head. Or blow him up with a grenade or, for that matter, a missile launched from a drone.

So I don’t think that the “helpless” classification is correct legally.

Second, neither the UCMJ nor international law requires our military to give an enemy combatant the opportunity to surrender. This is different from the rules for police who, absent extraordinary circumstances, are required to offer a chance to surrender. It may be prudent in some circumstances for our military personnel to offer surrender, but it is not required legally.

[Continued]

[Continued]

Third, neither the UCMJ nor international law require our military to always accept a surrender. They must accept a surrender if it is feasible in the circumstances. As examples: (1) if a portion of enemy combatants on a firing line surrender, but others do not, the surrender of the few (or the one) does not have to be accepted; (2) if the mission is such that acceptance of surrender is otherwise not feasible — such as a special forces infiltration, where taking a prisoner would risk disrupting the remainder of the mission — then the surrender need not be accepted.

I think that this is the general state of the law, and I agree with these principles morally, as well.

On the issue of torture generally:

(1) I agree with several others that the EIT’s used by the US, including waterboarding, are not “torture.” Waterboarding is very serious, and should be used very sparingly, and it is my understanding that the US followed this rule.

(2) I believe that “torture” is morally justifiable in extreme circumstances. I’m thinking of the “ticking time bomb” or similar scenarios. The general requirements are: (a) it is reasonably necessary to save “innocent” life, and (b) it is used on someone who is in “guilty” of creating the risk to the “innocent” life in some meaningful sense.

If this is “consequentialist,” then I see no moral problem with being concerned about the consequences on this point. I generally oppose killing people, too, but make exceptions for self-defense, defense of others, and reasonably “just” war. These principles could be criticized as “consequentialist” also. I just don’t see anything wrong with such “consequentialist” thinking.

(3) As Justice Scalia once said, I find myself getting “older and crankier,” and am currently morally ambivalent about the use of injury or pain in other circumstances, such as corporal punishment. As a policy matter, I still oppose serious corporal punishment (e.g. flogging), because of the potential for abuse.

I’d shut down the prisons and bring back flogging as primary form of punishment. But that’s just me.

Here is what I take to be the relevant provision of the UCMJ:

I’ll have to get the citation later. The question of who is a prisoner is perhaps debatable, but to walk up to an incapacitated man and shoot him dead strikes me has barbaric. I realize this happens, and since I am not a veteran I pass no judgment in specific cases, but to encourage such things takes a toll on the national conscience. Indeed, the belief among most Americans is that our soldiers are morally better than our enemies. We all realize that war is organized chaos, and that immoral things will inevitably happen. But that, it seems to me is regrettable.

I do not see your sleeping enemy example as particularly relevant. He may be asleep, but he is able to wake up and defend himself. An enemy combatant who is unable to fight back should not merely be killed. If that were permissible there would be no POW. We could shoot surrendering enemies willy nilly. I do not see that as a positive thing–even if it would bring an end to hostilities.

I cite the UN Convention for the purposes a setting out lines for the debate. The Convention, I argued, is at the extreme end of prohibiting all infliction of pain. The opposite end would be no restrictions. I am not endorsing the UNC. If I did so there would be no reason for the post. I have suggested that the best way to debate is to seek a middle ground. This should be fought out in the public square with an eye towards developing some limits, however small. That’s kind of what is happening here. One side for essentially no limits, another side insisting torture never be used, and most people finding some middle ground. The goal is to find a moral calculus for answering the question. I would like to see a post or two that lays out both the rationale for the extremes, and and one that suggests middle ground. These are, it seems to me, not academic questions. There almost surely will be another crisi and now we have a chance to form some principles.

AP, Yoo did not distinguish between pain and injury but rather he attempted to refine what was meant when law spoke of severe pain or suffering.

Congress defined “torture” as an act committed by a person acting under the color of law specifically intended to inflict severe physical or mental pain or suffering (other than pain or suffering incidental to lawful sanctions) upon another person within his custody or physical control.

Yoo concluded (based on how Congress had defined the term in other statutes) the term meant physical pain amounting to torture must be equivalent in intensity to the pain accompanying serious physical injury, such as organ failure, impairment of bodily function, or even death.

It was. The demonizing of Harris and LeMay is simply historical revisionism.

I’ve never understood the people who get all exercised over Hiroshima but don’t even seem to know about the firebombing of Tokyo.

That’s part of the question. Is that the morally correct definition of torture? I have great respect for John Yoo. He was called upon to research and develop a cogent analysis of the legal issues. I haven’t read his recent book, but in his interview with John Stewart he explained that the urgency of the situation after 9/11 required that he come up with legal principles that could be applied to various cases. That was an extraordinarily difficult task. But right now, and before we find ourselves in an equally difficult situation, we, as a nation, have the opportunity to come to some conclusions that are consistent with out shared values.

We prolong this entire mess by failing to fight effectively. We are fighting savages with one hand tied behind our back, because our technology allows us the luxury of doing so. In the end that only means more innocent people will suffer, and the vast majority of those will be poor and Muslim. Here is a rule, based on the behavior of our enemies.

If they abide by the Geneva convention and the UN declarations, then we do too. If instead they target civilians, commit mass murder of non-combatants, execute prisoners by setting them on fire, then all bets are off and a little bit of water-boarding and sleep deprivation is OK by me.

Thanks for the correction. It’s been several years since I read the Yoo memos.

Apparently including the Japanese leadership at the time, because the firebombing of Tokyo didn’t seem to phase them a bit.

Waterboarding during SERE training is meant to teach our soldiers to resist torture during capture. That makes the line far more blurred than “we do it to our own soliders so its not torture.”

There is also the matters of degree and duration. Its all well and good to waterboard someone once for a short period of time during SERE, but the amount we did it to say KSM was far beyond that. Its also extremely glib to say that sleep deprivation is like college but there is a vast difference between an all nighter and 3 or 5 days without sleep – the psychological damage is well known and documented.

Waterboarding during SERE training is meant to teach our soldiers to resist torture during capture. That makes the line far more blurred than “we do it to our own soliders so its not torture.”

Waterboarding during SERE training is meant to familiarize soldiers to an effective interrogation technique. If we intended to train them to resist torture we would need to break their bones and refuse to set them, break out the thumb screws, or perhaps hold a few fake executions.

Well that depends on how you define torture doesn’t it?

A lot of smart and knowledgeable people classify waterboarding as torture. A lot of people who have been through the process call it terrifying and torturous.

Me? Having never been through the process I can’t know for sure, but waterboarding skirts a line too close to moral depravity for me to support it.

Well that depends on how you define torture doesn’t it?

We have a definition of torture, it comes to us courtesy of the U.S. Code. Torture is defined as the intentional infliction of severe physical or mental pain or suffering. Now we have subjected thousands of servicemen to waterboarding with no ill physical or mental effects, so the evidence strongly suggests it does not meet that standard.

If waterboarding didn’t inflict sever mental suffering why would it be effective?

Sleep deprivations severe effects on a persons psychology are well documented.

Again you are ignoring degree and duration in this rather glib assessment.

What constitutes “severe”?

If waterboarding didn’t inflict sever mental suffering why would it be effective?

Sleep deprivations severe effects on a persons psychology are well documented.

Because it is terrifying but that is not synonymous with torturous.

And those we subjected to sleep deprivation were monitored by doctors to mitigate the possibility of those effects.

What constitutes “severe”?

What does not constitute severe is that which thousands of people have been subjected to with no ill effect.

se·vere

səˈvir/

adjective

1.

(of something bad or undesirable) very great; intense.

“a severe shortage of technicians”

2.

strict or harsh.

“the charges would have warranted a severe sentence”

I don’t see that in the dictionary definition at all. I think a lot of pro-waterboarding folks are hiding behind obscure language instead of making the case that the torturous techniques they advocate were both necessary and effective.