Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

How to Think About Inflation and Deflation — James Pethokoukis

How to Think About Inflation and Deflation — James Pethokoukis

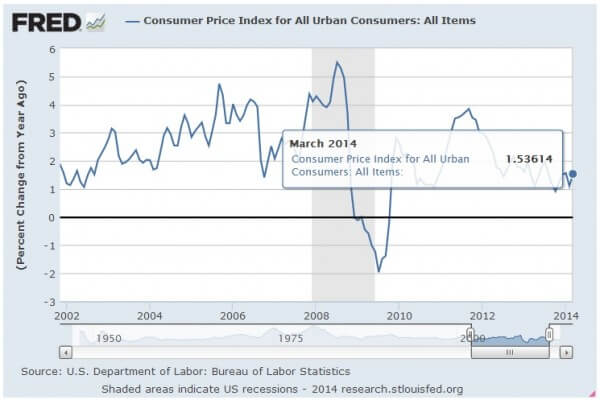

The March consumer inflation numbers showed prices rising faster than expected and up from last month. In the 12 months through March, consumer prices increased 1.5% versus 1.1% in February. The core CPI, which strips out the volatile energy and food bits, rose 1.7% versus 1.6% in February.

The March consumer inflation numbers showed prices rising faster than expected and up from last month. In the 12 months through March, consumer prices increased 1.5% versus 1.1% in February. The core CPI, which strips out the volatile energy and food bits, rose 1.7% versus 1.6% in February.

Analysis from IHS Global Insight:

Overall, the consumer inflation story is relatively bland. However, the direction of food prices is somewhat worrisome. Average consumers will have no cause to consider inflation rampant, but living standards will suffer as a larger percentage of household budgets are spent on grocery store bills, leaving less for discretionary spending.

Overall, inflation really is benign, especially given the Fed’s avowed 2% target. In fact, some economists have been worried that inflation has been too low, maybe risking outright deflation. As AEI economist John Makin wrote in a recent report, “Inflation is falling in the United States, Europe, and China, suggesting a real threat of impending deflation that could cripple the global economy.” To get some more insight on inflation, I asked a few questions of Makin, and economist/blogger Scott Sumner of Bentley University:

PETHOKOUKIS: There seems to be concern out that that inflation is running too low. But isn’t low inflation a good thing? Isn’t that the great Volcker victory of the 1980s? Along those lines, are some kinds of inflation and deflation good or bad?

MAKIN: Low and steady inflation is a very good thing. Volcker withstood immense heat for the pain tied to bringing inflation down from 10% to about 3%. But the benefits were substantial– avoiding destabilizing higher inflation and setting the stage for a huge equity bull market after 1982′ when he relaxed tightening. The drop in inflation cut tax receipts so much that the deficit rose faster than expected – a constructive form of fiscal stimulus.

Relative price changes, brought about by rapid price increases or decreases in some goods/ services are good and self-correcting. But when most prices are rising or falling consistently, movements can become self- reinforcing and damaging to the economy. Higher inflation is usually more volatile. That boosts uncertainty in a way that has been shown empirically to harm growth. Disinflation is fine, until and if it turns into deflation which almost always is associated with lower growth, weaker investment and higher unemployment — as in the Great Depression and In Japan after 1997.

SUMNER: Never reason from a price change. Whether inflation is good or bad depends on whether it is supply or demand-side inflation, and whether aggregate demand is currently excessive.

In short: (a) Supply side inflation is bad, but it isn’t really the inflation that hurts, it’s the fall in real GDP from the adverse supply shock. Thus holding nominal GDP constant, higher prices mean less real output, which is bad; (b) Demand side inflation can boost both prices and output, which can be good. But only if the economy is currently depressed from an adverse demand shock. In my view that’s been true of the US economy since late 2008, although it becomes a bit less true as unemployment falls back closer to its natural rate (which is hard to estimate.)

In my view it makes more sense to talk about boosting nominal spending than boosting inflation, because that language better conveys what the central bank is actually trying to do.

In terms of the trend rate of inflation, Volcker was surely wise to bring it down from double digits. But all he did is bring it down to 4% in late 1982, where it remained throughout the rest of the 1980s. Today it’s about 1.5%, so a bit higher inflation would be needed if the Fed is serious about its 2% long run target. There are costs and benefits from a lower or higher trend rate, and no one (including me) knows what trend rate of inflation is optimal. I suspect it’s close to 2%, but the exact rate depends on other aspects of policy. Under current (inept) Fed policy it’s probably close to 3%, as that makes the zero bound on interest rates less likely.

PETHOKOUKIS: It looks like the ECB might start a quantitative-easing, or bond buying program. Would that help the EZ economy?

MAKIN: The usual criticism of incipient QE or other anti-deflation measures is that they won’t work. Japan suffered under this delusion for 15 years until late 2012. Successful reflation requires a higher inflation target from the central bank that it is committed to meeting with substantial money printing until prices start to rise– the exchange rate starts to fall. A central bank has to credibly promise higher inflation to beat deflation. Many cannot bring themselves to do it, as is I fear, the case with the ECB.

SUMNER: QE would help in the eurozone, but I’d prefer they set a nominal GDP target, or if they continue to inflation target they should do level targeting of prices, which means promising to catch-up for any shortfalls from their inflation target (assumed to be about 1.9%).

Published in General

Theoretically, printing money should work, but I’ve heard a lot of skeptical economists on whether it actually does. I think banks are hesitant to use the “free money” because if they lend it out and fix deflation the Fed will jack up rates and leave them holding the bag. So battling deflation doesn’t work very well because the actions necessary go against the bank’s rational self interest.

It also goes against the interest of borrowers because they don’t want to borrow money when they’ll have to pay it back with more valuable dollars.

If it’s successful in counteracting deflation then they’d actually be paying back with devalued dollars. Besides, if they need to borrow then they will borrow; need/want doesn’t go away.

To add to what Mike H said, how it was explained to me was that there’s a psychology behind it. If people in my network have been getting laid off and I took a wage cut, even not considering interest rates, I would probably go into full scrimp and save mode. You can give people all the money you want but if they’re stuffing them in a mattress prices still fall resulting in lower revenues, more layoffs, more saving…

I think economists call it velocity of money but I’m not sure. I could be wrong.

People are not central bankers though and if it’s not successful your mortgage payments are increasing monthly. It’s a big risk for an individual to take to solve a collective action/national psychology problem.

A lot of these wars over monetary policy seem to come about because we’re asking too much of it. Jim P’s post seems reasonable, and Sumner and Makin have a point of view that is not crazy. But while I don’t think Sumner’s monetarist prescriptions would have a bad effect, I doubt they’d have a good one either. The fiscal and regulatory regime is so idiotic (idiotic in the way that only Ph.D.’s could conceive) that it seems the best monetary policy would only preserve a lending environment that is as sane as possible in its future expectations. Unfortunately, even in a world with stable monetary expectations, no one will take risks if it not clear what business regulations are in effect, or if there’s great uncertainty as to where government spending is likely to occur, or if entrepreneurial ventures are threatened with high taxes.

First of all, savings is a good thing that we need more of in every way in our country; this consumption that we’re so addicted to turns out not to be entirely real; it’s somewhat dependent on too-easy credit which is going to run out eventually – catastrophically btw. Even still, if prices keep falling then sooner or later the money will come out of the mattresses (I say sooner). People don’t stop needing and wanting things. Pink slips aren’t issued en masse as soon as inflation reaches zero.

Anyway, psychology is dodgy enough applied to an individual let alone an entire economy.

“Sumner said no one knows the optimal rate of inflation but it’s ok so long as it’s low and stable.”

Zero’s the optimal rate of inflation for savers. 2% is good for the US Gov’t, not so good for savers. 2% was arrived after a consultation with that famed philosopher, Jean Baptiste Colbert, who advised, “The art of taxation consists in so plucking the goose as to get the most feathers with the least hissing.”

Taxation via inflation is known as Seigniorage:

“Some economists regarded seigniorage as a form of inflation tax, redistributing real resources to the currency issuer. Issuing new currency, rather than collecting taxes paid out of the existing money stock, is then considered in effect a tax that falls on those who hold the existing currency.”

The danger of seigniorage, and the untrustyworthiness of the sovereign, is why the gold standard emerged, historically.

It’s not like the government is hiding anything. The Fed has an inflation target (now, at least), which allows the government to borrow 2% of GDP in a sustainable manner (the government still has to pay interest on it, so it’s not entirely free). By the way, the word “seigniorage” doesn’t refer to the inflation tax; its the interest the Fed earns on it’s bond portfolio (remember that it always invests the money it creates, usually in Government bonds but more recently in mortgages).

It’s really not that much; the Fed has earned more profits in recent years due to its bond buying programs, but not that much more.

Think of it this way, Tuck. As consumption taxes go, inflation is great. European countries raise their VATs all the time, but no American politician would dare propose passing a 5% inflation mandate.