Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Intro to Thomas Kuhn: What Actually Is a Scientific Theory?

Intro to Thomas Kuhn: What Actually Is a Scientific Theory?

Probably the most standard answer these days is “A falsifiable one!”

Probably the most standard answer these days is “A falsifiable one!”

That’s standard Karl Popper. Specifically, it’s Popper’s answer correcting for the bad philosophy of Logical Positivism.

And what’s wrong with Logical Positivism? I talk about that a lot in some videos on this playlist, but it’s not especially important for this post. Also, Logical Positivism did do one thing well: It actually had a pretty good theory on science.

Instead of answering that question with “A falsifiable one!,” the standard answer from Logical Positivism is “A verifiable one!”

Not bad. But not entirely right either. It’s missing something. Something like . . . like falsifiability, maybe. If you have to choose between just those two answers, I would recommend Popper.

Still, there’s something . . . something weird about Popper’s philosophy of science. He thinks we can’t solve something philosophers often call “the Problem of Induction.” For our present purposes, that only means this: Popper doesn’t think science can give us any knowledge that a theory is true. (If you want a more detailed intro to the Problem of Induction, try this YouTube intro from me, or this Ricochet post introducing it.)

So you see the problem with Popper, right?

It’s all very well and good to say that only a falsifiable theory can be a genuinely scientific theory. That may be the correct answer to the question of what science is. This is Popper’s most famous point, and I’m not disputing it. And it’s also all well and good to say that science can give us knowledge that a theory is false–it can. So far, so good for Karl Popper.

But if science can’t give us any knowledge that a theory is true, then science is just a very sophisticated exercise in human ignorance.

And that doesn’t seem quite right.

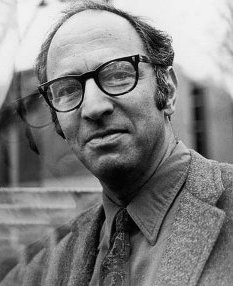

There’s another major philosophy of science out there that might help. And if it doesn’t help, at least it’s interesting! That would be the philosophy of this guy, Thomas Kuhn.

Since this post is already long enough and since the real reason to post this post was to advertise one of my new educational philosophy video series, let’s wrap it up with SIX POINTERS on Kuhn, and then that advertisement.

Ready? Here we go:

- First pointer: Kuhn, like the Logical Positivists and Popper, is trying to get a clearer picture of the general (and correct) idea we probably all have of science: a method of investigating the physical world that involves making hypotheses not fully consistent with just any set of data and then conducting experiments that are likely to give us the data we need to test those hypotheses.

- Second pointer: Kuhn does not say science is subjective, although people sometimes say that he says so. (But it’s been said that Paul Feyerabend takes that view, and I can’t tell you otherwise.) Kuhn just says science is not entirely objective.

- Third pointer: Kuhn thinks certain scientific views achieve the status of paradigms. Paradigms aren’t just big theories. They’re theories that play a role in determining how we perceive the world, how we interpret data, and even what data we think need most to be interpreted.

- Fourth pointer: Kuhn thinks science solves puzzles during times of what he calls “normal science.” This basically means working with an old paradigm and filling in the gaps in how much of the world it can explain–figuring out how the paradigm explains something or other that hasn’t yet been figured out.

- Fifth pointer: A paradigm tends eventually to run into a situation where there are puzzles it can’t solve. Later, a new paradigm takes over through a scientific revolution in which paradigm shift occurs–which basically just means enough scientists start looking at the world through the lens of the new paradigm.

- Sixth pointer: Kuhn’s theory actually includes his own account of the verification and falsification that the Logical Positivists and Karl Popper were talking about.

Well, not exactly the same things as verification and falsification, but fairly close.

I’ve recently recorded seventeen videos introducing Kuhn! Here’s where you can subscribe to me on Rumble, and here’s the Rumble channel for Kuhn where these videos have begun airing already. (The remaining ones should air on Thursdays, one each week.)

And then there are the same videos on YouTube, but airing a little later. Starting in September, I think; till then, the YouTube playlist just has me in the side yard at the old place in Pakistan talking about Jurassic Park.

That’s right: Jurassic Park–the book, not the movie–talks about scientific paradigms and includes a superb illustration of Kuhn. Not the most important reason to learn about the philosophy of science, but not the least!

Published in Religion & Philosophy

Sorry, I didn’t review my Comment before sending it. Here is what I meant to write:

“That you know no hard core physicists who seek the truth about the physical world for its own sake doesn’t mean there aren’t any.”

That I write something that could be explained by bad motives–intellectual dishonesty– doesn’t mean that that is the explanation. You have the option of always assuming that I am honest, and that when I write something that isn’t true, it is because of carelessness (as in this case) or honest error. This has been always my assumption about everything you write, and it has worked very well, so I recommend it based on personal experience.

You are absolutely correct in this, and I thank you for the gentle reproof.

My point was a little simpler, which is why I think it still means something. YOU know that being interested in the physical world for its own sake is also called “philosophy.” My point is merely that physicists consider themselves to be far above philosophy, even if they do not know that they might be engaged in it. And they certainly would not consider what they did to be a subset of philosophy.

Yes, I know plenty of physicists who are interested in the world for its own sake. Indeed, that interest sometimes approaches pantheism.

Sherlock Holmes was wrong. After you’ve eliminated the impossible, you still haven’t eliminated all the wrong possibles.

I am very surprised to hear these things. All of them contradict my impression of the level of general knowledge of the history of natural philosophy, the emotions (hatred, admiration), and self-awareness (what is my motivation for doing science? ) of virtually everyone who is doing pure science. In particular, in the thousands of articles I’ve read on pure physics (as opposed to applied physics==engineering), I’ve never seen a hint that the author is opposed to his chosen profession, let alone opposed with every fiber of his being.

Yeah, I don’t understand the popularity of that line, or that it is raised in legitimate debate.

As a general statement of a general strategy divorced from any context, you are quite right that the Holmes statement would be wrong exactly for the reason you described. No question.

That said, if we take the statement in context and seek its intended meaning, I believe the implicit meaning is along something like the following lines.

If you have N possibilities and you have correctly eliminated N-1 of them as being impossible, then even if “whatever remains” seems very improbable, nevertheless it “must be the truth”.

I believe the implied point is “It cannot be anything else because those options have been eliminated as impossible. Therefore the option that remains must be the true option.”

To properly generalize it for cases where you don’t have a single remaining possibility, one could say “whatever remains, however improbable, must contain/include the truth”. In other words, the truth has to be within “what remains”. The key is to shrink the circle of the set of “what remains”.

In context, the understood situation was that “what remains” had been narrowed down to the point where an admittedly strange and seemingly improbable conclusion needed to be drawn (and was confirmed to be the truth). The point is that Holmes was not afraid and did not hesitate to draw the strange, unexpected conclusion, despite the strangeness, because logic drove him to a conclusion one might not have expected.

Science is a method of learning about nature by testing ideas.

I quite agree that we may be trying to cut across the grain when we try to answer the question about the nature of science by thinking in terms of nouns instead of verbs. Yes, “science is a process”, a method, a way of doing something, and to grasp the nature of science, we won’t get there by thinking about it as if it were some “fixed body of facts”.

Anyone can have ideas about anything. But just imagining an idea isn’t science. To practice science, one needs to test the logical implications of ideas.

If X is true, then we should expect to find Y, and not find Z.

(Note this works even for historical investigations of past events we did not observe and cannot reproduce. Different competing causal explanations would leave different residual effects that can be tested.)

This might seem close to Popper’s idea that it must be falsifiable, but I think that way of putting it gives too much emphasis on the elusive question of whether an idea has the attribute that it can be fatally and finally defeated as false. “Falsifiability” casts it as an attribute of the idea and being able to reach a conclusive, final, negative determination.

I would rather put the emphasis and focus on the question of whether we can engage in the practice of testing. Can we test the logical implications of the idea in a way where it might fail the test?

My issue is that for practical purposes, N = N + 1. There is always another possibility. I have found and seen the process of elimination to be an extremely unreliable method of arriving at the truth (with the exception, perhaps, of some technical troubleshooting exercises).

In practice, that is a reasonable and fair point to consider.

If you are looking for a pea and think to yourself “Which shell is the pea hiding under?”, you might think you have eliminated all the shells but one. Conclusion: It must be under the last one? But did you consider that there might be other possibilities, e.g. that the crafty fellow manipulating the shell game in front of you has slipped the pea into his hand or his pocket?

I offered the N vs. N-1 description as a simple way to easily understand an idea, but I agree that in practice it is often not as neat and tidy as that. That’s why I also wrote about trying to shrink the circle of the set of “what remains” as small as possible.

I would still maintain that it is perfectly legitimate to operate in terms of eliminating ideas that are not viable in light of evidence. There is nothing wrong about seeking to make progress by eliminating the impossible. That is real progress.

But the good reminder I take from your point is that in science we must always hold inferences tentatively. At any time we might realize that we had been assuming the pea had to be under one of the shells (and consequently fighting and arguing about which shell claim was the least bad explanation of where the pea was), but then discover the true answer was not under any of the shells we were considering.

That too is part of the Holmes point. He did not exclude the strange possibility.

Whenever I see something of dubious logic attributed to Sherlock Holmes, I am reminded of some of the Peirce scholars I know who believe that Peirce was the model for Holmes. There are a lot of coincidences between the the person and the character, not the least of which are the prickly personality and drug use. Peirce even solved a minor crime, in England IIRC, in a very Holmes-like fashion. But Doyle did not understand logic as Peirce did, so Holmes’ solving a crime based in deductive reasoning left out Peirce’s initial step, abductive reasoning—creating a hypothesis to test. Similarly, I know Peirce had said things that could be muddled enough to be was Holmes is claiming. The closest I can remember is a criticism of someone (Poincare?) that Peirce thought was using Bayes’ Theorem incorrectly. Peirce says something like, [he] seems to think that all things that are possible are equally likely.

Way far afield from the topic, sorry.

Of course, Peirce scholars might have a reason to “believe that Peirce was the model for Holmes.” ;-)

As to the acknowledged Inspiration for the character …

See also Inspiration of Sherlock Holmes concerning how “Bell was involved in several police investigations”. There have also been fictionalized dramatizations of Doyle clerking for Bell.

To wrangle this back to the topic, as a surgeon involved in the practice and application of medical science, Bell needed to engage in abductive reasoning “from minute observations” about symptoms or the residual effects of past events back to the unseen cause that explains the observable effects.

If X is true, then we should find Y and not find Z. What then do we find?

That is the nature of the practice of the method of science.

Oops, and I don’t want to wrangle off-topic

My opinion is different. I state it without justification, just to make people who have been brought up in the conventional wisdom know that other ideas exist. No conversational dialog is possible between holders of my opinion and their’s.

Natural philosophy (pure science) is the search for a satisfactory model–one that passes certain tests– that explains the real world.

We are taught by the schoolmarm’s, as Mencken called them, that the agreement of a model with observational data is a sufficient test of acceptability. Simply pick equations out of the air, pick constants out of the air that fit the curve to the current data, and you have an acceptable theory until falsifying data appear.

That is the scientific philosophy of “positivism”, a counterfeit of real science.

The fact that real scientists have always rejected many models that were consistent with the facts so far

is not explained by the schoolmarms. The description that the great natural philosophers themselves have always given of the actual anti-positivist tests of acceptability that drove them to discover their revolutionary models is simply ignored. Another fact that the drone-teachers conveniently forget: The fact that certain theories, like the Bohr atom, were even rejected as failing the minimum test of scientific acceptability by the same scientists who introduced them! Like Neils Bohr.

Positivism is the only philosophy that is tolerated by most of the educational establishment because it is so quick and easy to teach in the early-stage Progressivist society, with its promises of universal “education”. Teach to masses of students by masses of teachers, most of whom lack the spirit of independence, the intellectual curiosity, the capacity for abstract and critical thinking, and what I will call the “scientific instinct” required for real science.

Positivism requires little ability to think critically or abstractly on the part of teacher or student.

It helps the cause that maintaining a population of citizens who are incapable of critical thinking–even those who do have the intellectual capacity and the instinctive curiosity to learn to think, if well-taught–is in the interest of the political class when the latter is committed to a long-term project of enslaving the masses.

In particular, an electorate that is incapable of scientific thinking but indoctrinated in positivism will accept, without questioning, economic positivism. The despotic class is dedicated to the eradication of scientific economics because all the economic promises of communism and its precursors (welfarism, interventionism, fascism, socialism) are proven false by true science.

Not “possible”? You seem to claim a distinction from what I wrote. Yet speaking for myself, nothing in my position makes dialog impossible. Why would you suppose dialog impossible?

Did you think that something I wrote excluded “the search for a satisfactory model … that explains the real world”? If so, exactly what?

Certainly anyone can form any model they find “satisfactory” according to any criteria they prefer, whether theological, philosophical, aesthetic, intuitive, or something else. None of that is excluded. But I suspect you would agree that simply choosing a model one personally finds “satisfactory” is not of itself “science”. Kepler may have thought the model that planetary orbits are defined by nested Platonic solids was a “satisfactory” model, but he isn’t practicing science until the model is subjected to testing against reality. I would guess that is included when you write “one that passes certain tests”. How do you perceive that acknowledgement of yours to be incompatible with anything I said about science as a method of learning by testing ideas? Would you prefer this longer and more restricted variation?

Science is a method of learning about nature by testing models for explaining the real world.

Except I don’t advocate positivism. I never advocated what you describe. What I did do is describe the testing required of satisfactory scientific models.

An infinite number of pleasing models are always possible. Testing is what makes a search science.

Yet another reason to read The Abolition of Man by Lewis.

Not that this is what you folks are talking about, but Kuhn does talk about circumstances in which dialogue is nearly impossible.

https://rumble.com/vlort8-kuhn-why-people-with-different-scientific-paradigms-cant-fully-understand-e.html

I don’t think that link will work, actually. I think it’s the last one I uploaded. Probably not scheduled for at least a few weeks.

I have become convinced, largely through years of failed attempts at Ricochet conversations, that there are two distinct personality types, call them P1 and P2, with respect to the mental processes involved in reading, reasoning, and writing. Call my personality P1. From what you wrote I infer that you likely have type P2.

In my observation, it is not possible for people with these two different styles to communicate on any abstract subject, especially a controversial one.

Yes. Your criteria.

See below.

Non-scientists find the criterion of positivism satisfactory. It isn’t a personal preference: it is one that they were indoctrinated with.

With scientific thinkers it is personal. They instinctively find the criterion of positivism unsatisfactory.

But don’t assume I mean that it is personal in the sense of varying from person to person, like tastes in ice cream. In fact, every person who thinks scientifically finds the exact same criteria necessary for a satisfactory conceptual model. For example,

We know from introspection that that’s untrue: it doesn’t describe how real theoretical scientists actually do science. Also, without a conceptual model being created by scientific thinking, it isn’t even possible to make measurements of reality.

By the fact that consistency with facts is a sufficient criterion for you, and a necessary but insufficient criterion for a natural philosopher.

To a positivist, only.

Can you elaborate on P1 and P2? (If you already did, sorry; I muse have missed it.)

I already wrote “I don’t advocate positivism.” (I don’t agree with positivism. It is self-defeating.) Yet you seem to choose to disregard my statement and reassert the opposite. (On what basis?)

I wrote, “I never advocated what you describe.” (i.e. “that the agreement of a model with observational data is a sufficient test of acceptability.”). You seem to choose to disregard that as well. (On what basis? Where did I say what you wrote?)

I also wrote, “What I did do is describe the testing required of satisfactory scientific models.” Required = Necessary. I’m claiming that testing is a necessary aspect of doing science. How is it that you are so sure that I cannot mean what I say I mean?

I seem to recall someone writing “You have the option of always assuming that I am honest, …”. That fellow also said when they have chosen to make this assumption, “it has worked very well, so I recommend it based on personal experience.” I hope that generous fellow joins the conversation. Soon I hope.

I wrote, “Kepler may have thought the model that planetary orbits are defined by nested Platonic solids was a “satisfactory” model, but he isn’t practicing science until the model is subjected to testing against reality.” Ie testing is a necessary aspect of “practicing science”. (You said likewise.) There is no “science” that is devoid of testing.

I am at a loss to interpret your reply.

Kepler didn’t test his ideas? Didn’t think testing necessary? What statement about Kepler was “untrue”?

I often begin to think I have a handle allowing me to balance on the first or second step of understanding philosophy, and then my head smacks right into a sentence like this one:

Dieter Henrich characterised Hegel’s conception of the absolute as follows: “The absolute is the finite to the extent to which the finite is nothing at all but negative relation to itself” (Henrich 1982, p. 82).

Or maybe I should just avoid Hegel. But he seems to be part and parcel of the modern day philosophy student’s making.

Did you have any particular philosopher or philosophy that seemed to be a stumbling block to advancing further?

Yes. Hegel.

I try to keep a handle on the basics when I need to, but usually I just ignore him and study the philosophers I can understand. People who write for clarity and edification.

An interesting book on Science is David Wooten’s 2015 opus,

The Invention of Science: A New History of the Scientific Revolution

This gives a granular history of the development of “Science” beginning in the late 16th and early 17th Centuries:

“Modern science was invented between 1572, when Tycho Brahe saw a nova, or new star, and 1704, when Newton published his Optiks, which demonstrated that white light is made up of light of all the colors of the rainbow, that you can split it into its component clouds with a prism, and that color inheres in light, not in objects.” [thus utterly refuting Aristotle on color]

Wooten credits Astronomy as the first science:

“There were systems of knowledge we call ‘sciences’ before 1572, but the only one which functioned remotely like a modern science, in that it had sophisticated theories based on a substantial body of evidence and could make reliable predictions, was astronomy, and it was astronomy that was transformed in the years after 1572 into the first true science. What made astronomy in the rears after 1572 a science: It had a research program, a community of experts, and it was prepared to question every long-established certainty (that there can be no change in the heavens, that all movement in the heavens is circular, that the heavens consists of crystalline spheres) int he light of new evidence. Where astronomy led, other new sciences followed.

He quotes Borges:

“Bacon, of course, had a more modern mind than Shakespeare: Bacon had a sense of history; he felt that his era, the seventeenth century, was the beginning of a scientific age, and he wanted the veneration of the texts of Aristotle to be replaced by a direct investigation of nature.” –Jorge Luis Borges, ‘The Enigma of Shakespeare’ (1964).

Borges was wrong. Shakespeare had a far more complex and profound view of his, and prior, and subsequent eras than Bacon. For example, Shakespeare, in a few words, captured his pivotal age, and the past, and the future, in a single phrase in the mouth of Hamlet: “There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.” In that phrase Shakespeare encapsulates the course of modern thought into an oblivion of relativism, as contrasted with acceptance of “truths” (however erroneous those might have been in physics or biology) of medieval thought. Bacon comes nowhere close to Shakespearean insight. But he is credited as the initiator of the concept of scientific method. Bacon was influenced to some degree by alchemy, and appears to have been under the sway of magic, and a romantic and utopian view of a New World Order, a new instauration, a somewhat wildly visionary view of a return to the state of the World before the Fall.

Unfortunately, that Baconian legacy continues to hold sway among not just “scientists” in our time, in their search for a “Theory of Everything,” but among the Progressives, Globalists, with their “Vision of the Anointed” and their New World Order.

Yes but I don’t think it would be helpful right now because it’s in the middle of a controversy about natural philosophy where many frequent contributors on one side have powerful feelings. To quote someone from that side from a couple days ago, they are opposed to the other view “with every fiber of their being”. (I forget who said that and it doesn’t matter.)

I completely understand these feelings, and completely sympathize with them.

But once they come out in the open, they tend to end civil discussion. It is best to avoid them, even if it means ending the discussion peacefully in order to do so. I am not afraid of a renewal of these recurring personal attacks–mockery and accusations of bad motives–but they don’t advance Ricochet’s objective, which is a search for the truth, not a desire for personal victory.

That’s funny, Mark. I thought that you had the P2 personality and Augie had the P1. Well, I suppose we’ll never come to agreement on this.

Let’s clear some things up.

Actually, that describes neither how skilled scientists do science nor the philosophy of positivism. Positivism has many hydra heads (none of which I recommend), but at its core classical positivism sought to tightly circumscribe true knowledge.

It is self-defeating because its own philosophical claims are neither a product of mathematics nor of science. “Commit it then to the flames.”

Is it defensible “that the agreement of a model with observational data is a sufficient test of acceptability”? No.

At several positions on the X-axis of a graph, place a dot at any Y value you choose. Mathematics reveals that there will be an infinite number of distinct functions that all pass through all of your dots.

Implication: Models that fit current data (e.g. global climate measurements during a reference period) may yet go wildly astray compared to subsequent observations (e.g. later predicting far more warming than is observed).

For humor, definitely see Spurious Correlations.

Testing against reality is the necessary, distinctive quality of practicing “science” (vs. non-science), but a correspondence during testing against the data used to make the equations is not proof that the model is correct. There can always be false models or too-simple models that can be made to fit any finite data set.

It seems that this then deifies statistics, something we unfortunately see on those young ones today who are underschooled.

For what it’s worth, the behaviors of him and me are both highly P1.

The reason I mentioned this unexplained theory was not to engage in some pathetic passive-aggressive ploy, but only this.

Classical natural philosophy circumscribed true knowledge infinitely more tightly, and still does. A positivist with a laptop can generate 1000 candidate theories in 10 milliseconds our that perfectly meet the one criterion of the positivist for a valid candidate theory, all of which are absolutely unacceptable to a Newtonian scientist before a single experiment is done.