Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Redesigning the Organ Donation Market

Redesigning the Organ Donation Market

There is no market for organs, so my title itself is misleading. US Code, Title 42, Chapter 6A, Subchapter II, Part H, Section 274e states:

It shall be unlawful for any person to knowingly acquire, receive, or otherwise transfer any human organ for valuable consideration for use in human transplantation if the transfer affects interstate commerce. The preceding sentence does not apply with respect to human organ paired donation.

Persons violating this law “shall be fined not more than $50,000 or imprisoned not more than five years, or both.”

So, in order for market forces to be introduced into the organ donation market, the law would have to be changed. The bit above regarding paired human organ donation is discussed in this fascinating episode of Freakonomics radio about systems of exchange where money isn’t allowed to trade hands… for instance, in organ donation. So the question becomes: How can we go about doing that?

The first thing we need to tackle is why this law exists in the first place. Ever since organ transplantation became a viable technology there have been people who have been opposed to it for a variety of reasons, starting with religious/spiritual objections, all the way down to the “ick” factor. This in turn has led Congress to pass this law in order to allay people’s fears that the poor could be exploited or that predatory doctors with rich benefactors in need of an organ would prowl the various sick wards of a hospital in search of desperate people in need of a quick buck.

In fact, the “predatory doctor” fear is one of the greatest concerns cited by people when asked why they won’t sign an organ donation card. To be fair, it is a fairly horrific thing to contemplate (as the plot of several horror films attests) a doctor assessing your body as a butcher might a hog. So, there is a well-established cultural taboo backing this prohibition. We don’t allow people to treat their organs as being “fungible” in the same way that money is.

The trouble comes when considering the unintended negative consequences of the ban. As a result of the fact that money can’t lubricate these sorts of transactions the market is “sticky” — there aren’t enough organs to go around because normal people don’t want to give up a perfectly healthy kidney in exchange for the satisfaction of a job well done and a not-inconsiderable amount of post-operative pain. However, the real unintended consequence comes in terms of lives lost and dollars spent.

Medicare spent $57.5 billion dollars on kidney dialysis in 2009 – an average cost per patient of $72,000 per year. 13 people die every day awaiting a kidney which never arrives. These are real costs – and ones we should be sensitive to.

By comparison, a kidney transplant costs Medicare about $106,000 for the first year and about $17,000 in maintenance each year thereafter. Keep in mind these were 2009 dollars and the costs are surely higher today. While it doesn’t take a genius to see that public health dollars would be better spent on transplants than dialysis, particularly considering the medium to long term, that also ignores the vast improvement in the quality of life which the recipients get from not having to live their lives around dialysis centers.

So how do we get from here to there? First we have to overcome people’s justifiable fears of exploitation. The paired-donation concept goes part of the way towards accomplishing this by allowing a person in need of a kidney to access a much broader range of potential donors, as a person who isn’t them can donate an organ in their name to a third party in exchange for a matching organ of their own. It’s totally voluntary. But this still limits the universe of potential donors to the family and (deeply committed) friends of those who need a kidney themselves. In order to better satisfy this need a broader net needs to be cast.

To that extent, I would propose that the current prohibition be lifted, and replaced with a system that works like this:

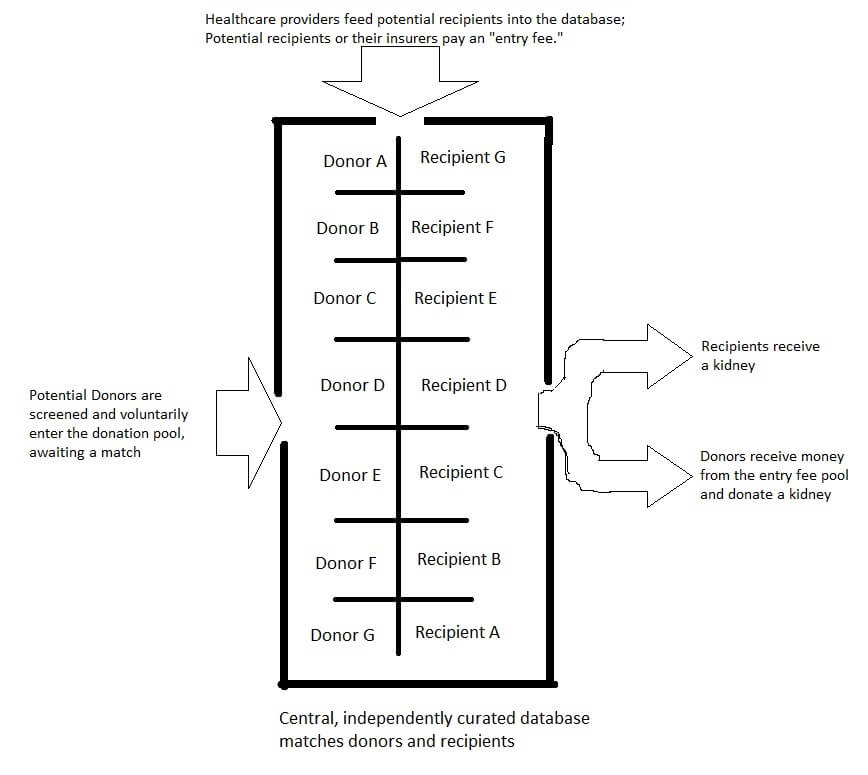

The only thing that the government needs to do is administer a database that matches donors to recipients on the basis of the relevant criteria — genetic and blood type compatibility. This will have the effect of making such organs more “fungible” and removing the appearance of favoritism.

So how would it work?

Healthcare providers would insert the recipient patient data into the database and it assigns them an alias, stripping the patient of all identifying marks to outside observers. The recipient, or their insurer pays a fee into the donation pool. The purpose of this fee is to reimburse potential recipients for their organ and to defray the cost of the procedures. The amount of reimbursement available would be the residual amount in the pool after recovering transplant costs.

Organ matching companies would similarly insert potential donors into the system on the basis of their blood and genetic factors. Their identity is aliased as well so that the system can’t be gamed by those seeking to broker an outcome – the technical details could include each company seeing a unique set of aliases for potential donors so that each company seeking to access the database won’t be able to distinguish one potential recipient from another. The database could also be designed to prioritize recipients on any number of criteria, from “length of time in the pool” to “severity of need.”

Certain rules, such as strict non-communication between donor-seeking and recipient seeking firms would have to be maintained, in addition to non-communication between the database operators and the donor/recipient. This would have the effect of making such organs as fungible as the dollars we are seeking to substitute them for.

But how do we set the fee for entering the pool? That too is simple: the insurance companies or the individuals involved will essentially have to bid on what they believe the appropriate price for donor remuneration and transplant costs will be. The relative motivation of the individuals and organizations involved will adjust the prevailing price for pool entry and thus, the amount of remuneration donors will receive. If the prices are too low, there won’t be enough donors and pool entry fees and donor payments will consequently increase as the motivation of the individuals seeking an organ goes up.

For example, say there are 20 people who have each paid $100,000 in the pool awaiting a kidney. Let’s say this leaves $20,000 per potential donor as a fee but there are no donors at that price – now a wealthy person comes along and desperately needs a kidney. The wealthy person donates $1,000,000 to the pool, increasing the potential payout to each donor significantly and suddenly, more people find that they are willing to part with a spare organ for, say $70,000 as opposed to $20,000.

In this scenario, rather than the wealth of some individuals representing a perverse incentive for the system to favor them, the largesse of the wealthy actually ends up favoring all potential recipients to some extent because their addition to the pool of available funds will have the effect of dramatically increasing the number of organs available.

Of course, additional rules such as the age of potential donors, their citizenship status and other factors would need to be considered, but in the aggregate, I feel as if this system would have the effect of improving the lot of people suffering with various chronic conditions. By divorcing the identity of both donor and recipient and inviting neutral third parties to match them we would allow the market to function and hopefully save a great deal of money and suffering in the process.

Published in General

You put yourself in the position of deciding which deaths are acceptable, just statistics, eh? (Don’t assume I am advocating the hypothetical position.) I am trying to explore parallels between the way you are justifying your position and the way an opponent of your position might think. If you hold them responsible for deaths due to lack of organ transplant availability, they can hold you responsible for deaths that they foresee from organ farming. (Larry Niven got a series of books out of exploring that concept.) Is it really unbelievable that a bioethicist would hold the life of a 20-something woman as worth sacrificing a 60-something man? If you take the position of current lives can be saved so hypothetical deaths don’t matter, you are in the same position as those who justify anything “if it saves just one life.”

No, you can’t hold someone responcible for someone else doing immoral things. A free market does not mean “organ farming,” whatever you mean by that, is permissible. An act doesn’t become permissible/impermissible based on law.

It’s usually wrong to stand in between two people transacting on their own terms. It’s also wrong to advocate for other people to do wrong things, as voting often does.