Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Two Parties Are Better Than Three (or More)

Two Parties Are Better Than Three (or More)

Why?

In a previous post, I mentioned, in passing, that the American, two-party political system has significant advantages over other democratic models and promised to expand on the matter another time. To that end, this post will discuss why there are two major political parties in the United States, how we arrived at this arrangement, and why that’s generally a good thing. This topic is especially germane given our current predicament, where both parties’ prospective nominees are phenomenally unpopular, and persons such as myself find themselves tugged between principles that seem irreconcilable.

As some people have recently discovered, the two major American political parties are private organizations that work in concert with state and local governments to set the timing and rules under which elections occur. Why do the states cooperate so completely with these ostensibly private organizations, even going so far as to foot the bill for the parties to hold private elections where they decide who their nominees and officials will be? Why doesn’t a third — let alone a fourth or a fifth — major party receive this sort of deference? The answer to that question rests primarily in the fact that our government is structured to have winner-take-all (“first past the post“) elections rather than the system of proportional representation found in parliamentary governments. In the language of game theory, American electoral politics is zero-sum and second place in an election is merely the first loser.

The practical consequence of this reality is that Americans — again, in contrast to those in parliamentary systems — are essentially forced to form our electoral coalitions before elections happen. We’ll touch on third parties again later, but in the meantime, here’s how the pre-election coalition-forming occurs:

(l-r: Democrats, Republicans)

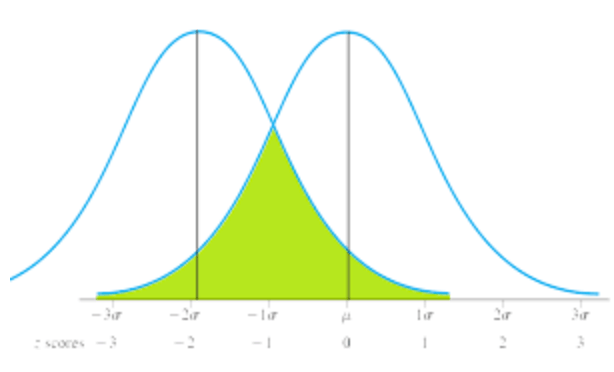

In a Hayekian, emergent-order fashion, the major ideological factions of the nation arrange themselves into a bimodal distribution prior to elections in order to give themselves the best chance of getting elected under this winner-take-all scenario. The parties’ centers of mass are situated to the left and right of the mean with the hope being that they are ideologically situated so as to attract enough voters in order to win elections. These clusters of voters are called the “Democratic” and “Republican” parties and consist, internally, of groups of people that sometimes have radically different agendas and interests. Nonetheless, they ally with one another under the banner of a particular party in order to gain political power.

(It should be noted that the means of the two modes have moved further apart in recent years, so the amount of overlap between the two parties has correspondingly decreased. This explains some of the ideological rancor that we’ve seen in recent years: As the parties have “sorted” themselves ideologically and geographically, the average member of each party has gotten further away from the average member of the opposite party, both literally and figuratively. It has been harder to find common ground as the rift has grown deeper.)

Now, contrast the American arrangement with a parliamentary system like Great Britain’s, where the prime minister is chosen by a parliament. Because parties often fail to obtain a majority of the vote (and thus, a clean majority) you often see absurdities like the Liberal-Democrats allying themselves with the Tories. For those unfamiliar with the Politics of Blighty, this would be like the Republican Party having Bernie Sanders and Barbara Boxer caucus with them in order to take control of the Senate.

Thus, this post-electoral coalition-forming is frequently necessary in order to seat a government, and causes unusual bedfellows to take up residence. It also means that voters tend to find themselves unable to know how their vote will ultimately relate to the governance that emerges, and end up essentially voting for a black box. Proportional representation (a system which democratically divides the legislature up by relative percent of the votes earned by party) only enhances this problem.

I much prefer our system. It tends to reward voters for being engaged in the process early (you can leverage the power of your vote in our primary system) and allows for people to be involved in the party’s process in a meaningful way rather than merely showing up and voting once.

As for third parties, another positive aspect of our system is how it discourages, rather than rewards, extremism. From a governing perspective, the American system offers little advantage to forming a political party that appeals only to the most leftward or rightward percent of the electorate, as failing to get a majority or a numerically superior plurality is functionally the same as getting nothing. This is unlike the parliamentary proportional delegation system, where a party receiving 10 percent of the vote gets roughly 10 percent of the representatives. The hope in forming such a party is to take part in a coalition government, assuming no majority has been won because of the fractiousness of the electorate. Thus, splinter parties can earn influence far outside of their actual representation on the basis of their ideological purity. As you can probably tell, such a system actively encourages extremism rather than moderation and consensus-building.

So, under the rules of the American electoral system, because of how the parties arrange themselves ideologically, there’s little room in between them where a third party could conceivably pick up enough votes to win elections, and there is precious little ideological space to attract voters. The “No Labels” movement claimed to be just such an organ, but you can see how that worked out. That leaves as the only credible option for outsiders the left flank of the Democrat party and the right flank of the Republican party. The best hope a group seeking to form a third party has would be to (paradoxically) peel off enough voters from the party nearest them to deny their own coalition a potential victory.

For this reason alone, both parties have a vested interest in heading-off third party challenges. The risk inherent to the system is that a third-party run from either side most likely results in elections being decided not by a head-to-head matchup between two well-matched ideological opponents, but a contest between one full-strength competitor and another who’s having to fend off an angry fan. You might think this is a flaw, but it works well as a safeguard, in that no party can stray too far from its ideological “lane” with impunity. If they were to do so, that party would quickly find itself facing a possibly lethal challenge from its flank or risking the alienation of those towards the middle of the overall ideological distribution.

I’ll leave it to the reader to contemplate what the effects will be as both parties slide inexorably to the Left.

Published in Domestic Policy

In my experience it does the exact opposite. Say you have two libertarians like Fred and I who would like to vote for the LP (this is hypothetical) but don’t because of the spoiler effect. We could list the Republican candidate second. In the instant runoff created by a preferential voting system our votes wouldn’t “help” the Demoncrat or the Socialist. It would allow third parties to thrive and bring new ideas to politics without forcing people to vote for 1 party they sort of agree with in order to prevent a party they sort of don’t agree with.

I could see it in a system where there is little-to-no limit on the number of candidates on the ballot. I don’t see it in a system where the ballot has one candidate per party.

Why?

And something like this approach might even allow a circumstance for an effective third party campaign to throw the Presidential selection to the House of Representatives. That’s about as far from the two party system as I would like to see us go.

I see the House as the principal form of enfranchisement for individual voters, not the President. When the President exercises a limited range of powers as was envisioned in the Constitution (federalism) this makes sense.

Firstly, it would negate your hypothetical example. In your example there are two LP candidates but only one DP candidate and one RP candidate. That’s doesn’t make much sense.

Secondly, it incentivizes collusion. Say you have a scenario where there’s one LP candidate, one DP, candidate, and one RP candidate. This (presumably) puts the DP at a major disadvantage. To counteract this imbalance, the DP creates a “dummy” party (let’s call it the “Progress Party”).

In this hypothetical, the RP and the LP are founded, run, and funded by completely different groups of people, but the DP and the PP are both funded by the same small cadre of donors, who can coordinate their activities. They solidify their hold on the strings of power by funding multiple parties.

If there were no limit to the number of candidates, collusion would be much more difficult to achieve. Just as in business, collusion is only possible in a protected market. Collusion becomes more difficult as the barriers to entry are reduced. Requiring one candidate per party is a huge barrier to entry.

This is essentially what would happen if ranked balloting is implemented up here in the Great White North. Right now, the powerful public-sector unions have to choose whether to back the Liberal Party or the NDP in a given election. Under ranked balloting, these unions would no longer have to choose. They’d always win, either way.

In other words, the German system with “Zweitstimmen” (“second choice ballots”).

Well no. The two party system enforces a bimodal concept of politics; by portraying politics as being just X v Y – other views don’t really have an opportunity to be heard because nobody can actively support them without throwing away their vote. Indeed, I despise Donald Trump too – but I still love to see Bill Kristol squirm now that he’s the disaffected one. Donald Trump is a perfect example of how destructive the two party system can be. You assume that the system will shut-out the radicals and crown consensus – by forcing radicals to join a coalition before the elections, so that a centrist wins either way. But a centrist will still form the coalition in a multi-party system as well – See David Cameron, Tony Blair , John Major, etc. None of them fire brand radicals. You can point to the Labour Party and Jeremy Corbyn as an example of radicals taking over a party in a multi-party system – But I can point to Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders (coming close) in the United States. At-least the disaffected in the UK have other alternatives, America now has no choice. In fact, one fluke this year; and we may be forced to choose between Trump and Sanders in 2016. I’d say that failing to hold up centrism.

Indeed, holding up centrism is also a fallacy. Centrism is completely relative to the times. Abolitionism was extreme in 1800, but mainstream in 1850 and universal in 1900.

That’s not quite true. Someone who does not “buy in” to either party’s brand can get involved with the party of their choice at the grassroots level and work towards changing the brand.

In the current two-party scenario where both parties’ brands have become pretty much set in stone, this is not a very attractive option, but it is still an option.

apologies for not participating; I’m on a 2 week vacation, but I will return rested and ready.

Yet there is an undeniable preference towards the status quo. The only option to try to be heard is during the primaries, at which point there are significantly fewer people paying attention – there is an established platform, and because the people who are paying attention are inherently those who have not been disaffected by the established position – you are nearly guaranteed to lose.

If this weren’t true – why don’t we just disband the GOP and force everyone to join the Democratic Party. Conservatives can just do some sort of grassroots thing, and try to change the DNC platform.

The fact is that this preference is completely arbitrary. The positions that are in the center change dramatically over time, and giving preference to the status quo only ensures that the status quo remains the status quo. Without good reason.

The simple fact is that there is no reason for structural bias towards the status quo.