Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Yes, I’m an Opera Singer. No, Not Like Charlotte Church…

Yes, I’m an Opera Singer. No, Not Like Charlotte Church…

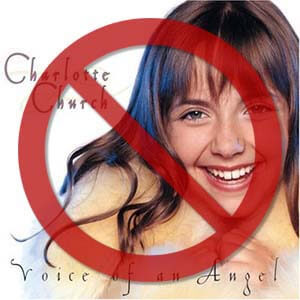

A recent conversation with a friend reminded me of something I dealt with frequently in my singer days. For years, after someone found out I was a classical singer, they would say excitedly, “Oh! You sing like Charlotte Church?! She has the voice of an angel.” At this point in the conversation I had three options: 1) Tackle them to the ground and slap them silly, 2) Explain in depth why Charlotte Church and Jackie Evancho are the products of amazing PR, but have been paraded and pushed beyond their vocal limits, ruining their voices in the process, or, 3) Smile and say, “Well, not really…”

A recent conversation with a friend reminded me of something I dealt with frequently in my singer days. For years, after someone found out I was a classical singer, they would say excitedly, “Oh! You sing like Charlotte Church?! She has the voice of an angel.” At this point in the conversation I had three options: 1) Tackle them to the ground and slap them silly, 2) Explain in depth why Charlotte Church and Jackie Evancho are the products of amazing PR, but have been paraded and pushed beyond their vocal limits, ruining their voices in the process, or, 3) Smile and say, “Well, not really…”

I usually opted for number 3, unless I felt the person had the interest and ability to understand my exegesis on the horrors of tween “opera singers.” For the longest time, my mother would always say, “You’re just jealous that she’s so successful.” Of course, every singer wants to be successful, but not like that. So I would like to shed some light on the education and development of young singers in hopes that y’all will never buy a Charlotte Church or Jackie Evancho album every again.

I once heard a violinist say, “Similar to the dolphin, who is not a part of the family of fish, the singer is not a part of the family of musicians.” While it was meant to be a jab at singers, there is some truth to it. Singers are unique among musicians. We don’t start training rigorously at age five the way instrumentalists do. Here’s how the timeline for a singer’s career should look, though some things will vary depending on the voice type:

16 years old: Well after puberty, start taking lessons. This point in a singer’s development is crucial. This is the age when the voice is limber and pliable, best for learning the building blocks of technique. It’s also the age when young singers start listening to greats of the opera world, and start begging their teachers to let them sing things like Puccini, Verdi, and heavy Mozart. What young soprano doesn’t want to sing the “Queen of the Night” or “Madama Butterfly”? Don’t do it!

A good teacher will put the kibosh on that, and if the teacher doesn’t, you probably need a new teacher. Allowing singers at this stage in their development to sing large, beefy repertoire is like allowing a scrawny teenager to try to bench press the same weight as someone that competes in the Crossfit Games.

The voice is a muscle, and needs frequent, healthy conditioning. If that singer starts singing heavy rep, it will literally ruin his or her voice within a few years. Why do you think that Charlotte Church stopped recording after age 17 or 18? Because she got a wobble in her voice you could drive a Mack truck through, and her career as a classical singer was over. Young singers at this age should be singing art song, light Mozart, Handel, and Monteverdi.

18 years old: Get a bachelor’s of music in vocal performance. Finding a good teacher is imperative, so it’s definitely worth the time and expense to visit different schools and take lessons with prospective teachers. Often times, teachers will offer a free 30-minute lesson for potential undergrad students.

Also, don’t let their resume fool you. Often times, the singers with the most performances under their belts are the least well equipped to teach. A lot of these singers are natural-born opera superstars. They can’t explain how they do what they do, and they sure as heck can’t teach it to a young singer.

Most singers are not born with an innately perfect technique. Most of us have to spend hours and hours in the studio and the practice room learning how to breathe, support, and project the sound in a healthy way that will last us throughout our hopefully long careers.

Singers are athletes, training their muscles to produce amazing sounds. Young singers at this point (with the exception of the coloratura soprano) should still be singing light, easy repertoire. Coloraturas are a little different — our voice type is high and agile, and blooms earlier than any other Fach. Because of this early bloom, if a coloratura hasn’t established her career by the time she’s 27, it’s not going to happen. This being said, an 18-year-old coloratura still shouldn’t be singing “Lucia di Lammermoor” or “Queen of the Night”.

22–23 years old: Decide whether to stay in academia or move to New York to try a performance career. Either way, finding a good teacher is of the utmost importance. At this age, singers might start expanding into some weightier rep, but should do so very cautiously.

28–30 years old: At this stage, the muscles of the vocal cords are stronger and less susceptible to being damaged. A solid technique should already be established by this time. As the voice ages, different colors will start to emerge. A soprano that was once a light lyric might find that her voice is now too warm and large for that rep, and she will start exploring some light Puccini and Verdi, as well as Gounod and heavier Mozart.

30s–40s: This is when the voice is in its peak. While singers still have to be protective of their instrument and not push, they can sing bigger, richer repertoire. If a career hasn’t been established by this point, it will never happen. The one caveat to that is the Heldentenor and the dramatic soprano- these are the voices that sing Wagner and Strauss.

50s–60s: Retire and teach.

So the next time you’re tempted to pick up that Jackie Evancho CD, instead might I suggest the selections below.

What a 16-year-old should be singing:

What the college-age performer should be singing:

What I was singing in my mid-late 20s:

For the coloratura in her 30s:

For the lyric soprano in her 30s:

What a dramatic soprano in her mid-late 30s sings:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FQ4sAJi4304

Published in General

Not what I said, the value of the training – not the appropriateness of the use of the technique in the correct place, two different issues. There is a difference. The value of the training is my point. Young voices can be taught to sing in a glorious manner, and in a highly demanding technical tradition, and that training can provide an outstanding foundation for a later even different singing career, without vocal damage for both girls and boys (as the rise of mixed choirs has shown). I agree, I don’t want my opera singers sounding liking an eleven year old boy-soprano from Hereford Cathedral. On the other hand, for choral music and for solo baroque music the less vibrato the better (within reason). The role of vibrato in pre-Romantic opera should be as a natural but highly controlled ornamentation. Besides, its all crap after 1825 anyways, decadent, emotive, melodramatic nonsense in opera, the only good stuff is in the orchestra.

That is an outstanding summary! I had no idea about the spectrogram, fascinating. Thank you for such a great answer to a difficult question.

Give me the Crowe over Auger (also lovely). The Crowe tempo is just a pinch too fast for my taste, but I think works (just barely), and her voice is a wee forced, but I love it. The only thing I didn’t like was the “body English” as my old organ teacher called it, stand still and stop acting. That I found distracting it’s oratorio.

As to the 12/8 version, too slow, and Handel (as far as we know) quickly changed it to 4/4 to help propel the brilliant aspects of the composition, and it appears it was never sung in the 12/8 version during his lifetime. It was also sometimes given to a tenor by Handel in performance.

For a very different British soprano I do love Isobel Baillie. Everything is wrong about it in some ways, but I still think it’s grand singing and wonderful diction. The old oratorio tradition had something.

The one thing that I think dark vowels cripples is English opera. The brighter vowels of English oratorio soloists from the early 20th century were a revelation when I heard them on 78 records in my late teens/early twenties. I had only heard the darker vowels of singers on CD at the time, mostly in period performance, and even when singing lines I was familiar with and have to go, I have no idea what she/he just sang, and was astonished that I could understand every word in their opera and oratorio selections from the 1920s through 40s. The tempos were too slow, the portamento too much at times, but the vibratoes weren’t too heavy, the vowels were clear (if not super-bright), the placement of consonants were flawless. These second shelf singers had a unique contribution to make to that musical world that is no more, one that the operatic English singers lacked.

Hi PsychLynne, What happened at and after your unique experience? One thing drummed into us in Junior High Chorus and High School Chorus was that if we altos sang tenor we would ruin our voices for alto singing, and that for all eternity. A counterexample would be most interesting.

Hi drlorentz, Thanks for mentioning this. Those other values include one certain value that occurs to me any time I see a star celebrity star, especially a young one. That is being in control of one’s own life.