Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

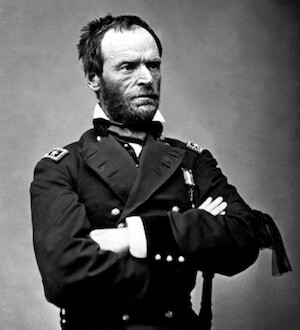

Sherman at 150

Sherman at 150

One hundred and fifty years ago this September 2, William Tecumseh Sherman took Atlanta after a brilliant campaign through the woods of northern Georgia. While Grant slogged it out against Lee in northern Virginia all through the late spring and summer of 1864—the names of those battles still send chills up our collective spine: Spotsylvania, the Wilderness, Cold Harbor — Lincoln’s reelection chances were declared doomed. All summer, General George McClellan reminded Americans that he had once gotten closer to Richmond than had Grant and at far less cost — and promised that, under his presidency, the war would end with either the South free to create its own nation or to rejoin the Union with slavery intact … but that in either case the terrible internecine bloodletting would end. Then Sherman suddenly took Atlanta (“Atlanta is ours and fairly won.”); McClellan was doomed and the shrinking Confederacy was bisected once again.

One hundred and fifty years ago this September 2, William Tecumseh Sherman took Atlanta after a brilliant campaign through the woods of northern Georgia. While Grant slogged it out against Lee in northern Virginia all through the late spring and summer of 1864—the names of those battles still send chills up our collective spine: Spotsylvania, the Wilderness, Cold Harbor — Lincoln’s reelection chances were declared doomed. All summer, General George McClellan reminded Americans that he had once gotten closer to Richmond than had Grant and at far less cost — and promised that, under his presidency, the war would end with either the South free to create its own nation or to rejoin the Union with slavery intact … but that in either case the terrible internecine bloodletting would end. Then Sherman suddenly took Atlanta (“Atlanta is ours and fairly won.”); McClellan was doomed and the shrinking Confederacy was bisected once again.

What was to be next? Southerners grew confident that the besieger Sherman would become the besieged in Atlanta after the election, as his long supply lines back to Tennessee would be cut and a number of Confederate forces might converge to keep him locked up behind Confederate lines.

Instead, Sherman cut loose on November 15, 1864 — despite Grant’s worries and Lincoln’s bewilderment — and headed to the Atlantic Coast in what would soon be known as “The March to the Sea,” itself a prelude to an even more daring winter march through the Carolinas to arrive at the rear of Robert E. Lee’s army, trapped in Virginia at war’s end.

After daring Sherman to leave Atlanta, and declaring that he would suffer the fate of Napoleon in Russia, Confederate forces wilted. The luminaries of the Confederacy — Generals Bragg, Hardee, and Hood — pled numerical inferiority and usually avoided the long Northern snake that wound through the Georgia heartland. Sherman’s army had been pared down of its sick and auxiliaries, but was still huge, composed of Midwestern yeomen who liked camping out and were used to living off the land. Post-harvest Georgia was indeed rich, and Sherman’s more than 60,000 marchers soon learned that they could live off the land in richer style than they ever had while occupying Atlanta. In their wake, they left a 300 mile-long, 60 mile-wide swath of looting and destruction from Atlanta to Savannah.

Yet there was a method to Sherman’s mad five-week march. He burned plantations, freed slaves, destroyed factories, and tore up railroads—but more or less left alone the farms and small towns of ordinary Southerners. His purposes were threefold: to punish the plantation class, the small minority of Confederates who owned slaves, as the culprits for the war; to destroy the Southern economy and remind the general population, as Sherman put it, “that war and individual ruin were now to be synonymous”; and to humiliate the Confederate military, especially what he called the cavalier classes that boasted of their martial audacity but would not dare confront such a huge army of battle-hardened troopers from Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, and other Midwestern states. In this context, the message was not lost: Unionists were not just New England Yankee manufacturers, but farmers who did their own hard work in harsh, cold lands more challenging than temperate Georgia; material advantages and repeating rifles were not antithetical to martial audacity, as a Michigan farmer with a Sharps rifle was more than a match for a plumed Southern cavalryman who boasted of killing Yankees.

Sherman was hated not so much because he killed Southerners: in comparison to Grant’s bloodbath in northern Virginia, probably less than 1,000 Confederates were killed during the March to the Sea. Rather, he humiliated the South by having supposedly less-audacious Northerners taunting the South to attack them on their own turf, and exposing the plantation class as hollow, showing them more willing to flee their rich and hitherto untouched plantations than to die while protecting them.

Was he a terrorist in destroying stately mansions, telegraph lines, and railroad tracks rather than searching out Confederate armies to square off in battle? Not really. His agenda of collective punishment aimed at ending the war quickly by starving Confederate armies of their ability to move, communicate, and be supplied. Sherman felt that it made no sense to kill young Southerners who did not own slaves when it was possible to destroy the livelihoods of those who did. He waged, instead, a sort of psychological terrorism, in which he sought to remind the Southern population that war was no romance, fought in far off places in glorious battle, but a dirty, nasty slog in which those who supported an amoral war would themselves have to pay some of its costs by the general impoverishment that followed the destruction of their leadership class.

Sherman’s legacy in Georgia is not akin to the blanket bombing of Dresden or Tokyo, much less to the nuking of Hiroshima or Nagasaki. Nor is it a parallel to the indiscriminate bombing during Vietnam or the war against civilians waged by the Taliban or ISIS. Rather, it resembles the selective targeting that the U.S. sought against Slobodan Milosevic or the current Israeli shelling and bombing of Hamas in Gaza. In both cases, the targets were those who prompted the war, the homes and offices of the Serbian and Gazan commanders and controllers. The general population itself was neither deliberately targeted nor left alone. The destruction of infrastructure that had aided the efforts of the Serbians or Hamas was analogous to the railroads that ferried Confederate armies or the telegraphs that sent orders to Southern commanders. Such material damage was not just “collateral” but intentional, as a bitter reminder to both the Serbians and the Palestinians of the wages of joining a cause that was not only wrong, but also as weak in the concrete as it has sounded savage in the abstract.

Sherman believed that a martial, if not tribal, society was especially prone to humiliation, especially those cadres who bragged that material disproportionality did not matter given the supposed superiority of their own individual warriors. Sherman was quite eager to disabuse Confederates of that myth, in the same manner, perhaps, that American pilots reminded Serbians that their beefy, scary killers were vulnerable, or that Palestinians are being reminded that otherwise normal-looking Israeli youths can decimate those in Gaza who brag of their willingness to blow themselves up against cowering Jews.

The South hated Sherman in a way it never quite did Grant, the grim reaper of Southern youth. Sherman was unapologetic after the war; he welcomed controversy and kept reminding his critics that the Confederacy was mostly hollow, prone to bluff but — on examination — weak. It was his duty, he continued, to remind both the North and the South of that paradox in ways that were hardly subtle.

George S. Patton sought to do the same to formidable SS divisions in France, as did the 1st Marine Division to the Japanese veterans who had butchered the innocent in China, as did American Marines in Fallujah to supposedly indomitable Islamic terrorists and insurgents.

Sherman would say to us that the way to destroy a martially audacious enemy is to enter his homeland, to separate the rhetoric from reality, to destroy things that aid the war, and to remind the population why most of their own houses and homes survive and why those of the most prominent usually do not—and why the general chaos that follows is somehow connected to their own blind support to those who have misled them.

Sherman is still hated for that, or, as Machiavelli put it, “men forget more easily the death of their father than the loss of their patrimony.”

Published in General

“Why are you fighting us?” – Northern Officer

“Because you’re here” – Southern Prisoner

The South is painted as the moral underdog in almost every facet of its governance and way of life. However when Stonewall Jackson won the Valley campaign his request to move on Philadelphia and/or Baltimore and “burn them to the ground” was denied by Davis and Lee on the grounds that this type of “warfare” was not worthy of the rules military conduct. Hence the South’s “Sherman”, Stonewall Jackson was denied the opportunity for a total war approach to split the Union in two. Lee’s march through Pennsylvania did not result in wholesale burning and theft of the countryside. He certainly did not poison water stock as Sherman did in Georgia learning that trick in the Seminole Indian wars. Yes, you can argue that the South was stupid for not following their total war opportunities and I am glad they did not.

What blows my mind about all the stuff I have read about the Civil War is why Fort Sumter had to be fired on. It seems clear that if the South had just seceded, stopped coming to Washington, D.C., formed their own capitol with their own constitution — that it would have been very hard for Lincoln to stop them and start a shooting war. He might have — but it would have been a very different moral calculus. Was it simply the hotheads who brought down the evils that come from war? Or was there more to it? I have never heard this explained adequately.

While it was foolish for them, in my opinion, to fire on Fort Sumter, Lincoln did everything in his power to incite warfare in Charleston harbor.

As far as I can tell from my research, Sumter was fired upon to provoke a reaction from Washington – preferably one where the militia was called out.

Why? Because the original Confederacy was economically unviable. It consisted only of the seven Deep South states. They were primarily agricultural. The only industrial centers were Atlanta and New Orleans. The Upper South, especially Tennessee and Virginia, was still in the Union. Absent a military confrontation they would not join the Confederacy.

In that case, all the United States had to do was wait out the South. It would have gone broke in a decade or so. Better for the Confederacy to roll the dice by triggering a war, so the rest of the slave states were forced off the fence. A Confederacy with all the slave states was economically viable.

As it was, half of the remaining slave states stayed with the Union, and fraud was necessary in at least two states (Arkansas and North Carolina) to secure secession.

Seawriter

Exactly. Ultimately, we might call it a mistake on our part to take the bait, but Lincoln intentionally provoked the firing by sending his ship in. He described this in a later letter as having the result he hoped for, even though he lost the fort in the process. It was a ruse to make his side look like the victim, attacked by those evil Southerners…who just wanted to be left the heck alone.

And to add my support to some earlier comments: waging “total war” against your brothers and (in your own mind) fellow-countrymen, especially when you are invading them, is unqualified evil. Rot in hell, Sherman.

Well, at least the ones who looked pretty much like you…..

I’m not going to refight the entire war here, but we could take that line and go back to the American Revolution, reargue every issue before women got the vote, and discuss the opinions of slaves in the states left in the Union.

Thank you, Seawriter. This is the great thing about Ricochet — all the thoughtful and informed people.

Was it explicitly discussed publicly in these terms at that time, among the first to secede? Or is this explanation something that was understood later by historians? It must have been at least discussed in detail at the time at least privately (not in the newspapers).

Give Lincoln his due — he had been wrestling with the slave owning mentality all his life. His election hung on it. He wanted it to end.

You and I don’t have to defend any slave owners or slavery. America was saddled with slavery because of the ethics of the time — Britain and all of Europe had these ethics which countenanced slavery. Our forefathers inherited the results of those evil beliefs that anyone could be enslaved.

You don’t have to defend being born in the south any more than I in the north. It was God who placed us where we are. War is evil and the simple thing is that it is better to bring war to a clear and definite end — that is what drives men in the duress of war to end it when it is possible, even at the expense of their own soul’s peril. These are truly difficult things to be responsible for.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki ended the biggest war in history. Thank God for that. The alternative was in every way worse.

My very “un-Southern” take on the thread on Sherman: the undying hate is about his success. He understood the South and how to beat them at war. The way Reconstruction went down was not his bag.

We now live in the age of “self” where every affinity group whether by blood or belief thinks it has a right to its own borders. It’s played out for thousands of years in the Middle East and more recently in the Balkans. It is still playing out here at home. And on Ricochet. Hell, VDH’s own state is considering become six. Our new–and perhaps everlasting–motto is “Out of one, many.” Let’s see how that works out.

It would not have been explicitly discussed publicly – except in the then-press equivalent of talk radio.

There was correspondence between the central government in Montgomery and the firebrands in Charleston prior to firing on Sumter about the concerns that the upper South was remaining in the Union. That included words to the effect it was going to take the Federal government taking direct action against the Confederacy to get the upper South off the fence.

One thing not appreciated today is the Confederacy was never so popular within the seceding states during its years of existence as it is today. In several states ballot fraud (or intimidation) needed to pass ordinances of secession. In at least four others (Texas, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina) there was armed resistance to secession. Regiments composed of loyal United States citizens were raised by the United States Army in every state in secession. While in some states these were mostly black regiments, there was at least one white regiment from every state.

Seawriter

And gang raping young African American women– in some cases doing so in three day sessions that Sherman’s boys called “relays” often ending in the victim’s death. They slaughtered livestock beyond their own use, murdered civilians, tortured by hanging old men and the black men they believed could tell them where the loot was buried… massive looting and destruction of property they couldn’t steal. They burned every home in their path and spoiled all the foodstuffs they didn’t steal. Before calling Sherman a hero take the time to read what he actually did in the march FROM the sea. Try South Carolina Civilians in Sherman’s Path: Stories of Courage amid Civil War Destruction by the historian Karen Stokes.

I wish VDH would read that meticulously researched work… and more.

I’m Ohio born, btw.

Very interesting, indeed, about these exact details. Both sides wanted the guns to fire but he who fires first is blamed. Lincoln was a very canny person in this — he got them to fire first. But, as you say, time was against the seceding states — and Lincoln clearly had more time. But the seceders had to strike soon or they would lose it all.

That is really important to understand and thanks for answering in such a substantive way something that I have asked many people about over the years and not gotten an answer that was this meaningful. I know I need to read more but it is a very daunting task to be knowledgeable about all the major aspects of this incredible war. And this exact item is definitely a major aspect.

At the time of separation, the arabs who inhabited the same territory as did the Israeli’s were offered their own territory, which was even larger than the land that the Israeli’s got. They chose war instead.

They now have no land to go back to, because they refused it, even to this day.

War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it. I count Sherman a hero exactly because he brought cruelty upon those who brought war, and thus brought peace.

South Carolina, especially. I’ve read that the US Army- that is, the “Union” Army- treated war as a business- that is, not personal- until it reached South Carolina.

Then, blaming that state for secession, the soldiery of the Republic endeavored to burn that state to the ground. And they apparently did, inspiring such plaints as this obviously woeful tome by Karen Stokes.

My sympathy is lacking, just as it manages not to appear for the poor, put-upon palestinians today.

To be perfectly honest, I yearn for an American leader who will do for our enemies today what Sherman did for South Carolina- that is, make them whine that their actions have consequences, which they regret- but which will also teach them to seek redress by other means than war.

Good Dr. Hanson,

I apologize for getting to this post so late. I have been inundated with both work and personal pressing duties. Also, Tisha A’bv interrupted my flow. I am now just freed up.

I have always liked Tecumseh. My father preferred US Grant but I have always liked Tecumseh. I relayed this story on Ricochet once before but in honor of Tecumseh’s birthday I will tell it one more time.

When I was in graduate school about a million years ago, I recklessly signed up for a women’s history course. I did it in all probability out of curiosity. Of course, we know that curiosity killed the cat. The professor was female and about forty. She was on her second marriage which was to the head of the graduate program that I was in. (The head of the program was on his fourth marriage just in case anyone is keeping score.) She seemed bright and pleasant enough.

On the first day of class there were about 14 students. Two were male. We sat around a long table with her seated at the head. The other guy, very hippyish in dress & demeanor, was on her immediate right. I, by chance, was sitting to her immediate left. She asked the question:

“In the movie Gone With the Wind which character did you most identify with. For the girls Scarlet or Melanie, for the boys Rhett or Ashley?”

The prof started to her immediate right with the hippy guy. It went around the table with me last. When it came my turn I said, “The only person who I identified with in Gone With the Wind was General Sherman because he burned Atlanta!”

There was complete silence. She stared at me for only a few seconds that seemed to me like hours and then she started to laugh. Whew, that was close. We wound up friends.

Anyway, I have always liked Tecumseh and I always will.

Regards,

Jim

I always thought that Ashley was poorly cast. He did not come off as anyone that any woman would want to be with. But not being a woman, maybe I misunderstand . . .

My mom has never been a fan of Ashley, either, thoug. She thinks he is too wishy-washy and easily pushed around.

Agree with Skyler and Tim H about Ashley Wilkes. However the movie does bring up a point with the portrayal of Scarlet and Melanie that does not discussed enough: the incredible backbone and support of Southern women to the cause during and after the war. The more I study the family journals and southern social history during the war and reconstruction the more I recognize the female participation is very much marginalized. Without the Southern females there would be very few of the museums, statues or other facets of historic preservation we have today. Of course the same could be said about the American Revolutionary and Colonial periods.

My favorite family story is one where my Father -in Law, at the age of 8, was caught singing “Marching through Georgia” by his Grandmother, a widow whose Husband was killed commanding a Georgia regiment at Little Roundtop, and she “switched” him until he could not sit down for a week.

Look Away—Very good comment about our ladies! I have my great-great grandmother’s diary, kept through most of the war, after the invasion of Middle Tennessee. Boy, did she have spirit! Some time, I’ll have to write a post about that. There was an A & E documentary made about her, ten years ago (I was interviewed in it), called, “In the Shadow of Cold Mountain.” One thing I discovered in her diary is an unwitting description of a Confederate special forces soldier, a member of Coleman’s Scouts, who was willing to suffer the reputation as a malingerer in order to be behind enemy lines and gather information.

So, as long as they’re not perceived countrymen, it’s ok? My grandmother never forgave the United States for the atrocities she saw — hospitals strafed, entire cities burned. But that was in Germany, so those guys must not have been evil.

Credit Sherman for teaching those quixotic “gentlemen” in the South what war actually is. Whatever glory attaches at the beginning of a bayonet charge pales in comparison to the destruction wreaked by a minie ball. As the kids used to say, don’t hate the player . . .