Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Virtue: More Than Its Own Reward

Virtue: More Than Its Own Reward

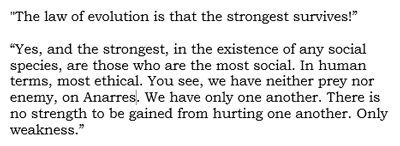

I recently read the Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed, an excellent novel that I highly recommend. The dialogue to the right got me thinking. The first speaker is from a decadent, stratified society, while the latter is from an extremely egalitarian, quasi-utopian one.

I recently read the Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed, an excellent novel that I highly recommend. The dialogue to the right got me thinking. The first speaker is from a decadent, stratified society, while the latter is from an extremely egalitarian, quasi-utopian one.

That the latter speaker — the protagonist, Shevek — is overstating his case is not lost on Le Guin, who’s quite honest about the shortcomings of Annarian society. But it suggests an important truth we often miss: Being virtuous isn’t just right; it’s usually smart, too.

I’m not saying that humans are inherently good and that we should all follow our instincts and the whims of our hearts. The best of us are broken, selfish, and prone to sin and vice. (The rest of us are far worse.) Temptation is a constant and inseparable part of the human condition, both in individuals and societies.

Nor am I saying that we should abandon all rules. Quite the opposite: Following the rules and living within the limits and constraints of a good society is a huge part of what I mean by goodness.

Nor still am I saying that it’s impossible to prosper through wickedness, or that virtue is any guarantor of success or prosperity. Counterexamples are too numerous to list.

But I am suggesting this: 1) In the aggregate, and all other things held constant, those who practice and seek virtue as understood within our Judeo-Christian-Greco-Roman-Enlightenment tradition tend to prosper; and 2) The same holds for societies that encourage and cultivate those values, as well as traditions such as the rule of law and free markets, and the classically liberal values of tolerance, openness, and free inquiry.

On the personal level, Charles Murray and others have noted that in the United States and similar countries, anyone of moderate talent who finishes his education, works hard, and marries before having kids is all-but-guaranteed entry into the middle class and a degree of prosperity, security, and comfort unimaginable to most of the world. To be sure, there are plenty of antisocial and immoral ways to make a good living — or better — but in modern society, these often come with significant risks.

On a larger scale, consider the incredible change in the way fortunes have been made over the past few centuries. To grossly over-generalize, you got wealthy before 1700 by getting other people to work for you, often through the use of exploitative political power. (There were exceptions, of course.) Since then, however, the fabulously wealthy have largely made their fortunes by providing goods and services that others desired in a free market. Exploitation continued, and in some ways increased over the short term, but it was generally incidental to the creation of wealth, not its source. And a wealthy society is, in general, stronger and safer than a poor one.

Now consider Victor Davis Hanson’s thesis in Carnage and Culture. He not only describes the way Western methods of war have repeatedly bested their competition, but how central the values of personal initiative, innovation, and a relatively egalitarian society have been to these successes. A Persian nobleman or German chief might have had far greater ability to demonstrate his personal glory on the battlefield, but the very tactics that allowed him to do so meant they were likely end their days cut to ribbons by a Greek phalanx or a Roman legion comprised of citizen-soldiers who could claim no personal credit for their kills. Likewise, it’s no coincidence that the relatively-free English triumphed with egalitarian longbows against the relatively-unfree French, who were much more reluctant to give commoners the means to kill an armored knight at a distance. Finally, consider the Islamic world’s struggles with modernity compared to the success of post-Enlightenment Christendom and cultures directly influenced by it.

Virtue and liberalism are no guarantors of success and happiness, nor are vice and tyranny inevitably punished in this world. But if we are to be serious about them, we should be honest about their strengths.

Published in Culture, Humor

The problem begins in the first quoted line. It is a mis-statement of evolutionary theory. It is not the strong who survive, but those who best fit their environment. It is why the hyrax and elephant can come from the same roots and are close kin, even though one is the size of a rabbit and has neither tusks nor long, flexible proboscis and the other is much larger with both features. Why? Because their long ago ancestors took different paths to fill environmental niches.

Are the most social necessarily the most successful propagators? Perhaps in some environments. In others, maybe being the most aggressively violent works.

I do agree with your suggestion, though. I was only disagreeing with the mischaracterization of evolutionary theory.

Correct, and the portion of Shevek’s response quoted here gets at that (as does the rest of the conversation). The first speaker is supposed to have an ignorant take on it.

It’s easy to overstate how common the archers were. Search for page 187 and you’ll get some of the debate, but the floor for a mounted guy often traveling with a servant isn’t that low. It’s still not aristocracy or royalty, so there’s a sense in which “commoner” is accurate, but that’s true of a lot of French knights, too.

Afternoon Tom,

VDH makes a good case that the Western way of war has been and is the most lethal. It is also true that Western empires have been long lasting. As you note in contemporary life, if you graduate from high school, don’t have children before marriage, and don’t get married before you are twenty, you will almost be guaranteed a life not threatened by poverty. All of these observations may be clearly true, however the more troubling problem is that we don’t know what aspects of culture are essential for creating or maintaining virtue and responsibility. We have seen with the rise in crime in the 60’s and the breakdown of marriage since the 60’s, behaviors which were once thought stable and solid can change quickly. Why do societies make culturally mal-adaptive (self-destructive) choices when the success of certain behaviors is so obvious?

Because it might hurt somebody’s feelings to call out the stuff that doesn’t work? That is apparently where we have gone.

Did something get lost in promotion? What dialogue to the right? I can’t find it on the Amazon page.

Fixed!

Indeed. Well done, Tom!

Actually, Plato said this first. In Republic. However, his appeal to virtue being more than its own reward relied largely on the afterlife. You argue that it works in this life. Awesome.

I really liked the Earthsea novels. The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed were so left wing as to be almost unreadable. I read them once. I couldn’t reread them.

I appreciate your point, Tom. The problem is, as Arahant suggests, that when virtue gets in the way of a value that is held more firmly, such as fairness and equality, people cave.

Actually, Solomon said that, in Proverbs, about 600 years before Plato. Striving to keep G-d’s law, and to be good, would help you to prosper and your family to thrive, in addition to the spiritual payoff.

Amen. Amen. Amen.

I have probably read The Dispossessed at least fifteen times.

I find it deeply engaging on the issues of solidarity and suffering.

I highly recommend it, although I can see why many find it distasteful with its anarchist atheist protagonist.

Anyone who could write The Dispossessed has absolutely no idea of human nature. I think that was the part that turned me off so badly.

Obviously I disagree.

Well, it’s been years since I read it. I may be reacting a little harshly.

No worries. As I said, LeGuin’s anarchic society that produces Shevek may be a barrier to readers. I, however, find much beauty in it.

There is a scene in which Shevek is talking about an accident that killed a man horribly. His skin was badly burned and those with him couldn’t even hold his hand to console him in death.

Shevek’s friend cries out that he is saying life and suffering are meaningless.

I find it deeply compelling.

I had a similar reaction. I don’t want to live in an Odonian society — and, as I said, I think Le Guin was pretty honest about its shortcomings — but I found much to admire in it.

Not quite following. Longbowmen weren’t as unique to the English, or armored calvary wasn’t as typical of the French? Both?

Yes.

Or, at least, we shouldn’t underestimate the degree to which it is often rewarding and adaptive.

If I knew, I’d ask Peter and Rob for a raise. :)

On the crime issue, though, things have gotten massively better, albeit at a high cost. On the matter of family morality, I agree this is almost certainly the great social problem of the day.

Most longbowmen and most knights were from the upper strata of the middle class.