Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Perhaps the Most Powerful Defense of Market Capitalism You Will Ever Read

Perhaps the Most Powerful Defense of Market Capitalism You Will Ever Read

Economist Deirdre McCloskey recently spoke in London, and this brief summary nicely captures her talk and her work on the power of economic freedom. Next year will see the arrival of her latest book, “Bourgeois Equality: How Ideas, Not Capital or Institutions, Enriched the World,” the completion of a trilogy on the wonder-working power of modern capitalism.

Economist Deirdre McCloskey recently spoke in London, and this brief summary nicely captures her talk and her work on the power of economic freedom. Next year will see the arrival of her latest book, “Bourgeois Equality: How Ideas, Not Capital or Institutions, Enriched the World,” the completion of a trilogy on the wonder-working power of modern capitalism.

Now, McCloskey does not like the word “capitalism.” She would prefer our economic system be called “technological and institutional betterment at a frenetic pace, tested by unforced exchange among all the parties involved.”

Or perhaps “fantastically successful liberalism, in the old European sense, applied to trade and politics, as it was applied also to science and music and painting and literature.”

Or simply “trade-tested progress.”

Here is a seven-page summary by McCloskey of that upcoming work, worth reading and rereading. And here is a summary of that summary:

Perhaps you yourself still believe in nationalism or socialism or proliferating regulation. And perhaps you are in the grip of pessimism about growth or consumerism or the environment or inequality.

Please, for the good of the wretched of the earth, reconsider.

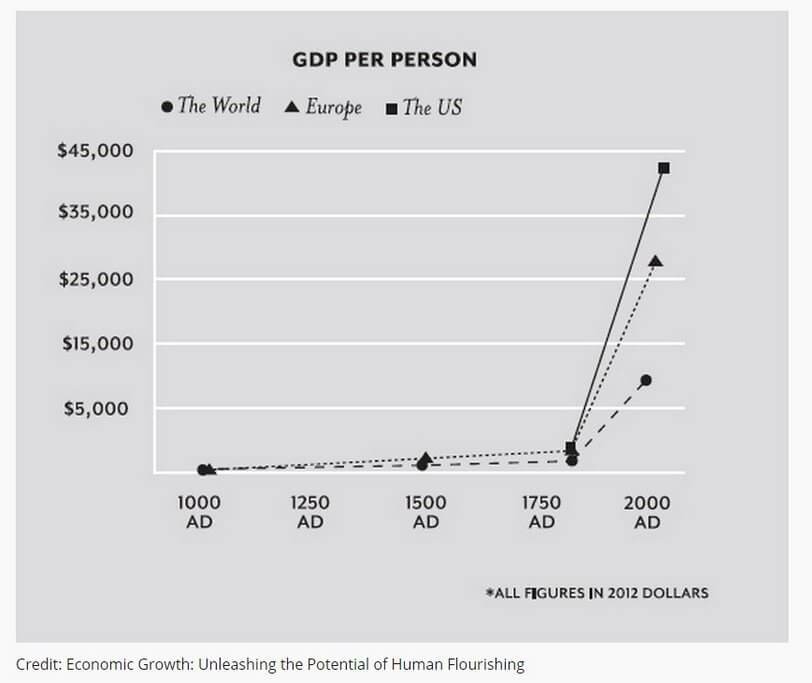

Many humans, in short, are now stunningly better off than their ancestors were in 1800. … Hear again that last, crucial, astonishing fact, discovered by economic historians over the past few decades. It is: in the two centuries after 1800 the trade-tested goods and services available to the average person in Sweden or Taiwan rose by a factor of 30 or 100. Not 100 percent, understand—a mere doubling—but in its highest estimate a factor of 100, nearly 10,000 percent, and at least a factor of 30, or 2,900 percent. The Great Enrichment of the past two centuries has dwarfed any of the previous and temporary enrichments. Explaining it is the central scientific task of economics and economic history, and it matters for any other sort of social science or recent history.

What explains it? The causes were not (to pick from the apparently inexhaustible list of materialist factors promoted by this or that economist or economic historian) coal, thrift, transport, high male wages, low female and child wages, surplus value, human capital, geography, railways, institutions, infrastructure, nationalism, the quickening of commerce, the late medieval run-up, Renaissance individualism, the First Divergence, the Black Death, American silver, the original accumulation of capital, piracy, empire, eugenic improvement, the mathematization of celestial mechanics, technical education, or a perfection of property rights. Such conditions had been routine in a dozen of the leading organized societies of Eurasia, from ancient Egypt and China down to Tokugawa Japan and the Ottoman Empire, and not unknown in Meso-America and the Andes. Routines cannot account for the strangest secular event in human history, which began with bourgeois dignity in Holland after 1600, gathered up its tools for betterment in England after 1700, and burst on northwestern Europe and then the world after 1800.

The modern world was made by a slow-motion revolution in ethical convictions about virtues and vices, in particular by a much higher level than in earlier times of toleration for trade-tested progress—letting people make mutually advantageous deals, and even admiring them for doing so, and especially admiring them when Steve-Jobs like they imagine betterments. The change, the Bourgeois Revaluation, was the coming of a business-respecting civilization, an acceptance of the Bourgeois Deal: “Let me make money in the first act, and by the third act I will make you all rich.”

Much of the elite, and then also much of the non-elite of northwestern Europe and its offshoots, came to accept or even admire the values of trade and betterment. Or at the least the polity did not attempt to block such values, as it had done energetically in earlier times. Especially it did not do so in the new United States. Then likewise, the elites and then the common people in more of the world followed, including now, startlingly, China and India. They undertook to respect—or at least not to utterly despise and overtax and stupidly regulate—the bourgeoisie.

Why, then, the Bourgeois Revaluation that after made for trade-tested betterment, the Great Enrichment? The answer is the surprising, black-swan luck of northwestern Europe’s reaction to the turmoil of the early modern—the coincidence in northwestern Europe of successful Reading, Reformation, Revolt, and Revolution: “the Four Rs,” if you please. The dice were rolled by Gutenberg, Luther, Willem van Oranje, and Oliver Cromwell. By a lucky chance for England their payoffs were deposited in that formerly inconsequential nation in a pile late in the seventeenth century. None of the Four Rs had deep English or European causes. All could have rolled the other way. They were bizarre and unpredictable. In 1400 or even in 1600 a canny observer would have bet on an industrial revolution and a great enrichment—if she could have imagined such freakish events—in technologically advanced China, or in the vigorous Ottoman Empire. Not in backward, quarrelsome Europe.

A result of Reading, Reformation, Revolt, and Revolution was a fifth R, a crucial Revaluation of the bourgeoisie, first in Holland and then in Britain. The Revaluation was part of an R-caused, egalitarian reappraisal of ordinary people. … The cause of the bourgeois betterments, that is, was an economic liberation and a sociological dignifying of, say, a barber and wig-maker of Bolton, son of a tailor, messing about with spinning machines, who died in 1792 as Sir Richard Arkwright, possessed of one of the largest bourgeois fortunes in England. The Industrial Revolution and especially the Great Enrichment came from liberating commoners from compelled service to a hereditary elite, such as the noble lord in the castle, or compelled obedience to a state functionary, such as the economic planner in the city hall. And it came from according honor to the formerly despised of Bolton—or of Ōsaka, or of Lake Wobegon—commoners exercising their liberty to relocate a factory or invent airbrakes.

And guess what? McCloskey will be speaking at AEI on Oct. 1. Please attend or watch online.

Published in Economics

Agree, but to play devil’s advocate one could look at that chart and claim the spike was a result of industrialization which could be independent of market capitalism. And before anyone jumps on me, yes I believe they are interconnected, though a bit loosely. There were pockets of huge growth periods in Florence and Venice and later in some of the northern European states before market capitalism which one could argue collapsed from political issues not economic. Political stability, colonialism, mass education, etc are other factors in that spike being where it is. Bottom line there are many reasons why at the end of the 18th century that spike occured. Capitalism is just one of them, not necessarily the whole reason.

Hmmm, how could the year 1000 GDP per person be what appears to be about 0? I’m not saying that things were not miserable and squalid then but – outside of famines – people at least ate. Even if a person just ate bread, in 2012, that would run a couple bucks a loaf. Annualize that, throw in some beer, and a new hoe to till the fields and you have a low number, but not essentially zero. I’m wary enough of statistics from 2015, and even more wary of trying to guess statistics from a thousand years ago. None of this is to say incredible progress has not been made in the last 100 years, just that the number could not have been 0 a thousand years ago

Now that is a hockey stick. Joe Bastardi showed a plot where longevity and humorously the percentage of the trace gas CO2 were also plotted and they all seem to be related. Our financial and physical well being, and CO2 levels are all tied up in cheap energy.

Just starting to read the 7 pager but “trade-tested progress”? No, no, no, no. There has got to be a better way of saying this. “Wordsmiths unite”. We have nothing to lose but conservatism’s stodginess.

I frankly did not much care for the author’s writing. Is her concept of “the Bourgeois Deal” really apt? It sounds too contractual (“you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours”). There’s no Judeo-Christian component of respecting ownership of self and the products of one’s labor, which must have evolved into recognition of human ‘rights’. Isn’t the concept of ‘human (eventually inalienable) rights’ uniquely a Western development?

Maybe she imputes too much to lady luck in where liberty and hence massive human productivity had its beginnings: “The answer is the surprising, black-swan luck of northwestern Europe’s reaction to the turmoil of the early modern—the coincidence in northwestern Europe … The dice were rolled by … By a lucky chance for England …

They were bizarre and unpredictable. … a canny observer would have bet on an industrial revolution and a great enrichment…in…China, or…Ottoman Empire. Not in backward, quarrelsome Europe”

An alternative (partial) explanation (source (?) “How the West Won: The Neglected Story of the Triumph of Modernity Hardcover”, by Rodney Stark): the Black Death caused a manpower shortage in Europe, which impelled surviving nobility to grant more autonomy and grant of lands to serfs because of the imbalance. …

[continued…]

Soon serfs became individuals with a developed a sense of their own worth, of a taste for what would become Western liberty, with its accent on freedom of action and self-ownership. “Liberty and dignity for ordinary people [that] made us rich” may have originated here.

Also, the prolific attainments of American frontiersmen and pioneers was due not only to the richness of the land they tamed, but to the freedom to till it and reap what they sowed. Once the frontier was opened, by folks with a Judeo-Christian value set mostly, the profusion of wealth we swim in today was foreordained, was it not? Freedom works. Why can’t she just say this and fill in the meat around these bones? Why invent awkward terms like “the Bourgeois Deal”? Was it really a ‘deal’, or was it a sense of self-ownership that would brook no violation? Once most Americans had experienced unbridled freedom, why would they accept anything less? Prosperity would then come as day from night. Would we find this kind of discussion in her three volumes?

“Free market” or “free enterprise” seem good to me, but they don’t convert well to an “ism.”

We used to have a great word for it. Liberalism. Then this word was somehow taken over by the other side, and discredited, so they’re back to being “progressives.”

Maybe “classic liberalism” is the best we can do.

Yeah, it’s hard to know what “liberalism” actually means these days. Would have been a good word if not co-opted.

Free Enterprise is a good one. Democrats talk a good game about freedom, but they regulate businesses so much that their support of Free Enterprise is honored more in the breach than the observance. However, this has to be augmented by something that gets at Republicans expectation outside enterprise per se, for example freedom of choice in schooling. “The Minimal State”? “Anti-Statists”?

Arcane and Patriot

Indeed. Progressives trashed their term so they stole liberal and there were few liberals left especially after the depression because of the universal false narratives controlled by socialists, marxists and progressives. Can we get it back? Conservative really doesn’t work. Libertairan is just as bad. Maybe we just go along with the progressives and insist they are progressives, secular progressives, modern socialists and gradually reestablish ourselves as liberal, starting with classical liberals, or foundational liberals, or constitutional liberals. They have trashed the term liberal as well, maybe they’ll let us take it back. It’s silly, but it matters.

What is the term the French use? “Market liberals” or something like that. To their credit, the French have been pretty consistent in their use of “liberal” when they speak disdainfully of the English.