Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Knowledge and Faith Can Be the Same Thing

Knowledge and Faith Can Be the Same Thing

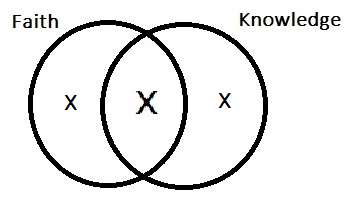

It is commonly assumed that an item of knowledge and an article article of faith can never be the same thing. This assumption is mistaken. In this post, I will explain only one point: trust in authority can be a source of knowledge. That’s what faith is: trust. It’s still the first definition of “faith” in the dictionary. Also see the Latin fides and the Greek pistis.

It is commonly assumed that an item of knowledge and an article article of faith can never be the same thing. This assumption is mistaken. In this post, I will explain only one point: trust in authority can be a source of knowledge. That’s what faith is: trust. It’s still the first definition of “faith” in the dictionary. Also see the Latin fides and the Greek pistis.

So don’t believe the hype that categorically separates faith from knowledge. This separation ranges from the view William James attributes to a schoolboy (“Faith is when you believe something that you know ain’t true”) to Kant’s more sophisticated idea that “I had to deny knowledge in order to make room for faith” (in beliefs that might well be true).

We should also reject the hype that says that an argument from authority is necessarily fallacious. The best logic textbook in print will tell you otherwise. It will even tell you that there is such a thing as a valid argument appealing to an infallible authority! (“Valid” is a technical term in logic; be sure to look it up first if you’re inclined to complain that there are no infallible authorities.)

Arguments from authority are good or bad depending on what their content is: and primarily on what sort of knowledge the authority is supposed to have, and whether it is reasonable to suppose that the authority really has it.

So an argument from a reliable authority is a good argument, and an argument from an unreliable or untrustworthy authority is a bad argument.

Protons and electrons: an article of faith

We must also dispense with the idea that science is the epistemological opposite of faith: one relying entirely on reason, one not at all. In actuality, religious faith usually relies on reason to varying degrees, up to and including this summary of Christian theology by Thomas Aquinas–quite possibly the most impressive bit of systematic reasoning in human history. And, if Thomas Kuhn is even one-quarter correct, science is not a matter of objective reason alone.

But the bigger point to be made here is that science depends on faith as much as your average religion. That is to say, it depends on trust.

Yes, of course scientific experiments can be replicated. But chances are pretty good that you didn’t replicate them, and that someone else did it for you. And if you yourself did replicate some experiments, did you repeat the replication in order altogether to avoid having to take someone else’s word for it?

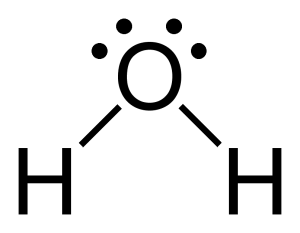

To skip over various levels of this exercise, here’s the end-point it leads to, using chemistry as an example. If you want to know something in chemistry without relying on trust, you will have to begin from the very beginning and repeat all of the experiments that led to the current state of chemical knowledge: all of them, multiple times each. You would die of old age before you caught up with the present state of chemical knowledge. And all of your hard work would be useless unless others had the good sense you lacked and were willing to take your word for it at least some of the time when you said that your experiments had turned out the way they had.

Even for scientists, scientific knowledge relies heavily on trust in testimony: the testimony of other scientists. As for the scientific knowledge of those of us who aren’t scientists, we are left where Scott Adams puts us in the Introduction to this book: depending on the word of people (most of whom we’ve never met) who simply tell us how things are.

Augustine (the real Augustine, the Church Father and founder of medieval philosophy) both here (chapter 5) and here (cartoon version here) is even more helpful than Adams. These are the sort of examples he uses:

- Do you know that Caesar became emperor of Rome about 50 BC? Yes; you know it by faith–by pistis, by fides, by trust–in the testimony of historians.

- Do you know that Harare, Zimbabwe, exists? Yes. But if you haven’t been there, then you know it by faith–by pistis, by fides, by trust–in the testimony of geographers or of people who have been there.

- Do you know who your parents are? You know that also by faith–by pistis, by fides, by trust in what they told you.

(On this last point my students instinctively think of DNA tests, at which point I explain to them that they would need not only to perform the test themselves, but to start from the very beginning of genetic science and reinvent it singlehandedly if the goal is to know who their parents are without taking someone’s word for something.)

The Resurrection of the Messiah: an article of faith

No doubt some readers will suspect that I am attacking the legitimacy of science. Not at all. To the contrary, I presume the legitimacy of science.

I am only pointing out that faith, being trust, is something on which science depends; and, since I am in fact assuming that science is a source of knowledge, other beliefs that rely on reliable testimony can also be knowledge.

What you need to get knowledge by trust is a reliable testimony. And we have plenty of reliable testimony: science, history, geography, and (for most of us) our parents. We live our lives by this testimony.

Thus, the crucial question for religious knowledge is this: Do we have any reliable testimony supporting any religious beliefs?

For example:

- Are there any prophets of Jehovah?

- Are there any holy books? Any books that are God-breathed and inspired?

- Is there a real Messiah who can tell us about God and about how we can know God?

- Are there several predictions about the Messiah made centuries before his birth which all converge on the same person?

- Are there accounts of the Resurrection of the Messiah coming from eyewitnesses of sound mind?

- Is there a Roman Catholic Church with infallible authority, or at least a universal church with reliable authority?

Well, yes. We do have some of these things.

And why should you believe me when I say that? That’s a good question. And, more generally, how do you recognize a reliable testimony in religion?

To ask this question at this point is to observe that I have only showed that knowledge and (religious) faith can be the same thing–not that they ever are. It is a possibility, but that doesn’t mean it is a realized possibility.

But that’s enough ground covered for one opening post. Maybe we can talk about whether this possibility is ever realized, and about how we can know whether it is, in comments, or in a new thread.

Note from the author: We did indeed talk about it comments. See comments #s 156-161 for a handy overview of my thoughts on that subject (and an addendum showed up in comments #s 182-183, and another one in comments #s 262-263).

Published in General

I think you are treating science as a body of knowledge analogous to a religious doctrine rather than as an epistemic method. I’m inclined to agree with you that to believe any particular purported fact (at least one not directly observed) requires an element of trust in some or other reporter(s), but I’m inclined to think of science more as a method than as a body of knowledge. Openness to falsification is a critical check inherent in the scientific method and over time, falsifiability provides feedback to truth claims and makes the self-correction of error an inherent part of the method. The principal distinction between a religious “fact” and a scientific “fact” then is not that one requires an element of faith and one doesn’t, and it is not that one is necessarily closer to an ultimate truth than another, but that one has the benefit of having been and continuing to be open to falsification and/or refinement. That openness provides some degree of assurance of truth, or at least movement toward truth, that religious faith cannot claim.

Augustine,

All and all a very nice post. I like your general theme. However, as you might expect from me I must mildly correct you on Kant.

Kant is referring to the phenomenon, already making a big impact in the 18th century, of hyper-rationalism. This is a rationalism that virtually makes a godless religion out of rationality. His point is very much your point. We can’t function without admitting that we have core beliefs that we take from authorities or simply claim them to be self evident.

Kant’s key word is a priori. It means before sensations. These are ideas that pre-exist. They are postulates, archetypes, and beliefs. Whether we assert that our beliefs come from Gd and/or his revelations or we are just trying to lay down self evident postulates like Euclid so we can derive some good geometry, we must accept some knowledge on faith. Otherwise we would have no knowledge.

Our responsibility is to be open and honest about this. Those that claim an absolute rationality usually have a hidden set of a priori assumptions that they refuse to acknowledge. This often leads to far greater problems then those problems that result from a responsible faith.

Regards,

Jim

This strikes me as setting up false equivalences over semantics by conflating two definitions of “faith.”

Obviously, when experts agree on a subject you should give their opinion much more weight than your own or another laymen.

So, expert opinion is a source of knowledge, but this is different in kind to religious faith.

Prima facie deference to expert opinion is just common sense. But expert opinion about religion tells us much more about the specific religion than the truth of the religion.

Thanks!

By all means. I’m not much of an expert on Kant. (But what I really expected from you was a good knife fight and praise for the glory of the Klingon empire. Oh, wait.)

Just to be sure: You don’t think Kant separates (religious) faith from knowledge?

(I may eventually reply with my own understanding of Kant. But that would take some work, and I’m hoping it won’t be necessary!)

I dig!

Until you factor in the theory of intelligent design.

Huh? I have no idea what you’re saying.

Well, I can’t reply to this without attempting a summary. Here are your claims, as I understand them, in bullet points. I’ll respond in the next comment.

Extended reply to Cato:

I’ll take the first point (obviously).

I’ll take the first half of the second point; I’m inclined to reject the second half, but I don’t think that affects this conversation much.

I like the first half of the third point, but I can’t agree or disagree since I’ve not yet formed a solid opinion on Popper (falsification) vs. Kuhn (success of a paradigm in solving puzzles) vs. the theory that science is demarcated by verification.

On the second half of the third point: I doubt all religious belief is closed to falsification. But maybe I should stick to my own faith here; Paul himself says (1 Corinthians 15, I think) that the Christian faith relies on the historical, factual, bodily, and witnessed resurrection. Can a historical claim be falsified? If so, my faith can be falsified; if not, my faith cannot be falsified.

I’ll grant the first half of the fourth point. Now the second half of the fourth point is not true of all religion, but I’ll stick to my own faith here and happily concede that there is a central core of it which is fixed.

Now, all of this is largely beside the point. I spend time on it because it seemed important. The really important point is . . . (in the next comment).

Extended reply to Cato:

My case for the possibility of religious belief can withstand all of these distinctions between religion and science.

I’m not arguing that there is a possibility of religious knowledge which is of the same nature as scientific knowledge, or even of the same quality. I’m just saying that religious knowledge is possible if there is a reliable testimony and a way to recognize it, and that religious knowledge would be similar to scientific, historical, geographical, and familiar knowledge in that it relies on reliable testimony.

My own faith is not best compared to scientific knowledge, in fact, but to historical knowledge.

On the first sentence: Indeed.

On the second sentence: Indeed.

But I’m not talking about expert knowledge about what a religion says. I’m talking about expert knowledge about what a religion says things about.

In one sentence, I am saying this: IF there is a reliable testimony about the things religions talk about, AND IF I can know that it is a reliable testimony, THEN I can have religious knowledge.

Of course, those are rather big IFs.

(I changed “region” to “religion” in the quote, and “difference” to “deference”; I think that was how it was meant.)

Augustine,

No not at all. Kant is a little hard to grasp at first. You see he doesn’t think his job as a philosopher is to invade the field of the theologian. He limits philosophy to answering human questions. However, he perceives the pure concepts of Gd, Freedom, and an Immortal Soul as necessary a priori postulates for all moral systems. Thus in a non-religious way defends the basic ideas of religion most rigorously. Often traditional theologians are appalled by this. However, he has not been out of favor for the last 100 years because of that. Faithless atheistic materialist reductionism and nihilistic agnostic formalist relativism, are scared senseless of Kant. They run from it like the bully who finally has to face somebody their size. They are the two dominant themes of the 20th century and now on into the 21st. They don’t want the ideas of religion or morality, even in Kant’s minimalistic fashion, to be taken seriously. Of course, Kant can do science and art really really well too. They should run.

Kant’s a bit much at home. It’s a bit like having a Lion as a house cat. However, on college campus where wolves, jackals, and other nasty critters abound, it’s nice to let kitty roar.

Regards,

Jim

The theory of intelligent design is synonymous with science. Many scientist do believe in it. It’s a theory based on so many things that are unexplained, and yet they exist. For instance the beginning of the Earth. (Before you jump on the opportunity, please hear me out) The beginning of the Earth, and it’s creation, is a pliable fact. There is no evidence to confirm an exact theory behind the creation of the Earth. This lays the same for how the Earth is situated in our universe, how it is bent on it’s own axis, how it’s consistent rotation and how near and far it is from the Sun allows it to sustain Life. As of now, there is no other model.

Yes they claim that there is the possibility that 700,000 other solar systems exist and the possibility of a planet like Earth is inevitable, but, and a huge “but”, that doesn’t change all the factors that are perfect in our universe to allow life to exist on this planet, or any other.

IF you’re able to do that, religion would be readily accepted by a number of truth-seeking atheists. If you can come up with unassailable knowledge and convincing arguments, people who are otherwise unconvinced by religion but open to convincing arguments would not resist.

As far as I’m aware, there has NEVER been an instance of this, and I would love to see it happen. It follows common sense that I should find it unlikely that YOU hold special knowledge in this area, but I would love to be convinced otherwise.

I’m going to take a page from your book and half grant this. Some religious knowledge (e.g. Jesus lived, died, and rose, etc.) is very much in the nature of historical knowledge and the evidence for it can be weighed in much the same way other historical claims can be.

Other religious knowledge (e.g. the trinitarian god, the forgiveness of sins, the last judgment) seems to me to be characterized by an entire absence of “reliable testimony and a way to recognize it” and thus by your terms is not capable of being “known” in any meaningful sense. No??

I’m familiar with intelligent design. I’m just not sure how it relates to my post.

A delightful and spirited defense of Kant!

Now as I understand Kant, he . . .

So I have understood Kant as arguing that we must believe in God while also arguing that we cannot know that God exists, thus separating faith from knowledge.

Now I’m confused. Is it the proven or the unproven. The relationship is equal between science and religion. The OP is relating that fact. How was the Earth created Cato? Have you ever wondered how the bible was written across multiple lands by multiple different people, who spoke multiple different languages and they all told the same story? Explain that in a scientific hypothesis. Then dissect it. Then prove it didn’t happen. Now come full circle and explain your logic.

Well, let’s not conflate knowledge with 100% certain knowledge; all the latter is the former, but not vice versa.

Let’s also not conflate knowledge with agreement. There is plenty of overlap between the two, but you can have either without the other.

And that brings us to a question: If indeed there is reliable testimony and a chance to recognize it, jointly leading to religious knowledge, why doesn’t it convince everyone?

The truth is that agreement, even agreement among intelligent and educated people, has never been a necessary condition for knowledge. (If it were, the first scientists to adopt a new and correct theory couldn’t know it; and no one would know much of anything about economics.)

But why doesn’t the case for a real item of knowledge convince every intelligent and informed person who knows of the case? In philosophical knowledge I usually suggest three explanations: sin, stupidity, and the difficulty of the subject matter; these (and other) answers are available in religion (and economics) as well.

Jolly good!

Well, not directly. But if we can know (historically) just a handful of things about the Messiah (miracles, claims to Messiahship and to divinity, and death and Resurrection), then we can know that He is a source of knowledge; thus anything He says can be known on His authority.

And if His authority can establish the authority of Apostles, Church, or Scripture as sources of knowledge (whether infallible or merely reliable), then their authority can establish the truth of these other doctrines.

I’m really more interested in the epistemological issues Augustine raised in the OP then in getting into another pointless pissing match over whether the Bible is true or not with somebody who’s obviously got his dander up over it. Sorry to disappoint.

I’m not sure if this falls under “difficulty of the subject matter” or not but it’s something of a commonplace that different observers will look at the exact same evidence and often draw different conclusions. That requires neither sin nor stupidity where the evidence — while perhaps sufficient for belief — is not strong enough to compel it.

Certainly all historical claims from the distant past are subject to meaningful uncertainty, and metaphysical claims about the operation of another realm run by supernatural beings are far more so.

You’re more interested in your point of view. The problem is, he’s right and you’re wrong, and that boils your blood.

Yeah, maybe I should include that in my list of reasons for disagreement on things knowledge of which is possible.

I guess technically that’s right. You can do that. But the more lines of attenuation you add, and the more fantastic the links, the more difficult it becomes to grant credence to the more remote conclusions.

For example, I have no trouble believing Jesus lived.

I am also not particularly skeptical about his crucifixion.

Once you start introducing the rising from the dead and the other miracles, however, you have strained my personal credulity to the breaking point and, at a minimum, materially heightened your burden of historical proof. Ancient texts are packed with well reported miracles which we rightly discount due to their sheer implausibility.

And I assume that those miracles are the marks of divinity that you contend give his purported statements about god, the afterlife, etc. credibility? If so, my skepticism about the miracles explains my skepticism about the rest.

I’m engaging in this exercise in part because it’s fascinating to try to parse out the differences between how a philosopher looks at these sorts of questions and how a lawyer does. To this day I am grateful for having taken an evidence class 25 years ago taught by a pompous blowhard who nobody liked and who taught us absolutely nothing about the legal rules of evidence. His passion was epistemology (I think he’s where I learned the word) and instead of teaching legal practice, he used this Socratic power to force us to examine hard how we thought we knew things, how we evaluated the probity of items of proof, how we drew and constructed sequences of inferences, etc. I hated every day of the class until the last one and then I missed it.

Ok.

That’s because you refuse to believe. With no plausible evidence. Argue all you want Cato. You won’t win this one.

Ok.

The more you attempt to outsmart yourself. I hope your dogs are healthy and you and your husband get that place in Michigan that you’re seeking. As for logic and science? Good luck.

Well, if we stick to this simple analysis then the quality of the knowledge does indeed decrease according to the number probabilistic facts (e.g., the probability of some doctrine in the Old Testament = the probability of the Resurrection X the prob. that Jesus claims divinity X the prob. that Jesus treats the OT as the Word of God X the prob. that the OT teaches the doctrine in question.)

If the premises are all sufficiently probable, this doesn’t have to be a big deal (any more than it’s a big deal to hold to the conjunction of 3 historical facts about Aristotle and 1 fact about what his Nichomachean Ethics teaches).

Also, if some stage of the system of religious knowledge establishes an infallible authority (in Messiah, Scripture, or Church), then things are considerably simpler.

Yes. My reasons for faith primarily consist of the miracles and (especially) the Resurrection, along with the convergence of many Messianic prophecies on Jesus.

Take away the miracles, and you take away at least half of the evidence for my faith, as well as some central doctrines.