Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Weimar as Rorschach Test

Weimar as Rorschach Test

Left: “Skat Players,” Otto Dix, 1920

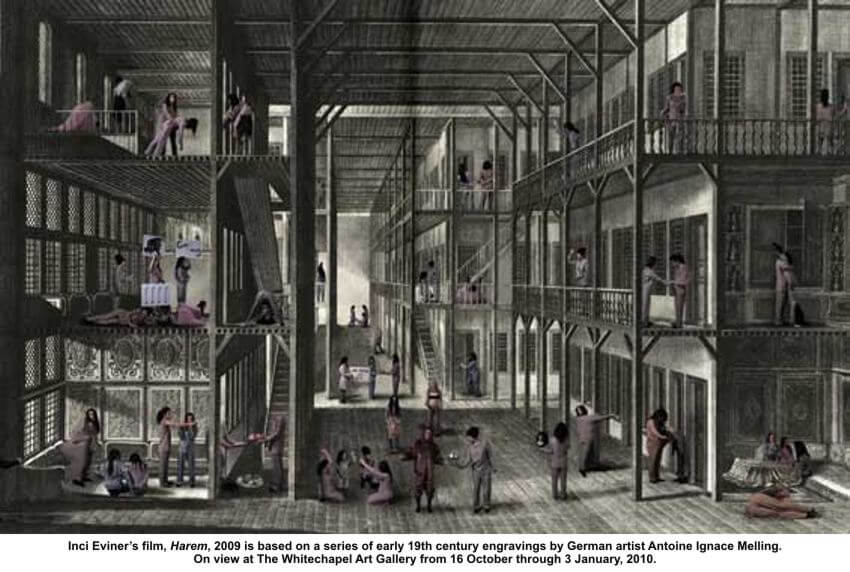

Above: Inci Eviner, “Harem,” 2009. (This is a still from the original work, which is a video installation–and a masterpiece. You can watch it here.)

It’s fascinating to see the way people responded to my question about Weimar cities. I find this question–about the relationship between a certain kind of political instability and a certain kind of creative efflorescence–extraordinarily interesting. Something struck me: People have immediate, instinctive responses to the word “Weimar,” and their responses say quite a bit about the way they view the contemporary world. I posted a similar question on my Facebook page, and here were some of the comments people left:

… Vienna, Rome, Paris, Moscow/Petersburg, Constantinople–all connected by the veneer of official and/or artistic displays of prowess that ineffectively mask the real chaos on the streets and in the minds of individuals.

… This is a remarkably fascinating question. I think you’ve actually hit a kind of universal typology. I think that many of the crises of civilization probably follow this pattern. Their vibrant culture actually intoxicates them from seeing or believing the impending doom. Perhaps Constantinople before the invasion of 1204? Many of the cities of east asia and eastern europe before their fall to communism?

… One word: hypocrisy.

Claire: … “The veneer of official and/or artistic displays of prowess that ineffectively mask the real chaos on the streets and in the minds of individuals.” This could almost be a definition of AKP governance–the proudly renovated Ottoman fountains, very pretty to look at and always adorned with a lavish sign saying “Renovated by your AKP municipality,” none of which actually convey water. Or the billion-page, slick “Earthquake preparation” plans that when closely examined are revealed to have nothing to do with any preparations actually made.

… Chilling idea in general; something does seem to be slouching towards Bethlehem.

… This is an interesting dicussion. It is strange that this group seems to see Weimar art and culture as marked by hypocrisy. Of course the right wing saw it that way (decadant, cosmopolitian, international, experimental, not sufficentaly tribal or nationalistic) but many see it and saw it as vibrant. Vienna 1900 was somewhat the same and this is the place that Einstein, Freud, Schnitzler, Klimpt, etc came out of. Perhaps dynamic vibrant culturaly mixed places are heightened by the sense of impeding doom or perhaps they are just very, very vulnerable.

… OK, I’m going to revote for Moscow 1917 and the Gov’t of Kerensky. Versailles 1789. Baghdad 1258? Constantinople 1453. Rome 410. Ctesiphon 637. Connect the dots and call it the “end of civilization” I could see it going as a broad historical phenom or as a modern phenom depending on whether you want to focus on the weakness of democratic regimes and the disintegration of culture or whether you want to do the ennui of the rich and civilized in the face of barbarism.

Claire: I’d like to take the discussion further from the (interesting) topic of “Which other cities were like Weimar Berlin” and more toward, “What were the distinguishing characteristic of Weimar Berlin.” Thoughts? I’m thinking of the unleashing of social and political imagination, the fascination with sexual adventure, the popular activism, the Utopianism, the feeling of life as something particularly intense and concentrated … the animation of artistic life by the confrontation with modernity; the death of the old world of princes and emperors; the end of the agrarian economy and peasant farming; the end of rigid class distinctions … the shift in the political center of gravity to the city, the cacophony of sounds and images, the artistic obsession with industrialization, the tensions and excitements of mass society, the new forms of artistic expression to which this awareness gave rise—abstract art, dissonant music, the architecture of clean lines, the heady enthusiams, the vibrant, kinetic energy … and obviously anyone who lives in Istanbul now will recognize these themes. More ideas?

… I think of a far less romanticized account: materialistic mobocracy, Bismarckian-statism, daily political assasinations and bombings, Ludendorff smoking a cigar with von Hindenburg as Germany declines, grotesquely vulgar naturalistic novels, compulsory intellectual uniformity, a trillion Marks to buy a slice of bread, meaningful national humiliation, as well as a grinding impoverished existence. I also think of the American Dawes and Young plans which saved the Germans from their awful economic calamity as well as at long last sanctioned their economy to breathe once more. Intense Anti-Semitism also comes to mind when I think of Weimar Berlin.

Interesting, no? This has me wondering: Was Weimar art in fact decadent, as the Nazis claimed? Can we predict the doom of a culture by looking at its artistic life? Or is the condemnation of Weimar culture the mark of the modern reactionary, in the full negative sense of the word?

Published in General

Three thoughts: 1) Is art prescient? The answer would depend on whether or not one feels that culturally advanced, or advancing, societies tend to evolve away from real work. By real work I mean the employment that elevated the society in the first place. I guess this would be akin to asking who baked Picasso’s bread. 2) Are culturally advanced societies hypocritical? Again that would depend on the level of public conformity to a general morality or set of public norms. The higher that level of public conformity to those norms, the higher the level of public hypocrisy. 3) Are culturally advanced societies destined for ruin? Yes, if the the society becomes disconnected from the mundane, often boring, duties that assure their survival. A precursor to this is always the importation of foreign labor to perform such tasks. In short, the foreign laborers do the jobs American’s won’t do. When art becomes the only labor worth the doing, put some jam in your pockets, cuz you’re toast.

Claire, a few years ago I went to an exhibit at NYC’s Metropolitan Museum of Art on Weimar Art and Otto Dix figures heavily in the exhibit. I was overwhelmed by the grotesque and sometimes savage depictions of human beings. To your question of predicting a civilization’s doom by its art, I think in this case you can. I think the art of Weimar Germany is starkly hopeless and ugly (but supremely interesting as a historical artifact).

When I read Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage–where the Parisian impressionist art scene figures heavily in the plot–the main character said something to the effect that artists paint the world as they see it. Van Gogh really saw the world in flames. Degas saw the world as tea-pot delicate. And Otto Dix and his compatriots really saw the world as hellish. And how could they not, considering the historical reality that they found themselves in?

I’m with E.E. Smith. The vibe I’ve always gotten from Weimar is nihilism, a profound brokenness, defeat, and hopelessness. Dix is a great example, but you can also look at the œuvre of Beckmann (perhaps Weimar’s most celebrated artist), e.g. Scene from the Destruction of Messina, Shipwreck, The Sinking of the Titanic, are pre-war works that are profoundly hopeless, but his turn to a harsher, cruder technique after the war in, e.g., The Bath, The Dream, the bleak Harbor of Genoa, seems significant.

The German Expressionist movement is suffused with a despairing dread, a Blick ins Chaos or Blick in den Abgrund. As much as you can point to English and French culture being broken upon the wheel of the First World War, the effect was much more dramatic in Germany—the country having suffered more (people ate grass when food imports dried up), the country having been defeated, and in some circles the perception of the illegitimacy of the defeat (Germany never having fought on its own soil).

Whether this reflected the inevitability of Weimar’s Untergang, I don’t know; I’m not big on inevitabilities. But it certainly adumbrated it.

So what do you see in Turkey’s future from that Inci Eviner piece?

I could be reading the Inci Eviner piece totally wrong — but the first thing I think of is prison. I see prison in everything from the monochromatic outfits and the dreariness, to the headless women and that repeating booming noise, which sounds like heavy footsteps or shackles hitting the ground…

The other thing about a prison is that prisoners lack an identity and, obviously, freedom. Maybe–and this might be stretch–but maybe this is the path Turkey’s going down with the AKP in power.

Glitter and Doom. A harrowing exhibit. World War One unleashed a level of transgression so vast and precipitous that similarly transgressive art, in response, seemed almost necessary to explain the world. Walking through image after image of decrepit men and mangled veterans and addled, exhausted whores, I grasped how it could be that a fringe movement which promised the ultimate overcoming of that hellish rot and ruin could rise to power so quickly and so completely. Nazi politics was the last artistic transgression produced by Weimar Germany.

Yes, absolutely. The sense overwhelmingly is of prison–or an insane asylum–characterized by hopelessness, despair, futility, madness, anguish. Note also that the video plays on a repetitive loop–the sense is that nothing can change. The word “harem” means forbidden, and obviously carries all the obvious allusions to the harem, which in Eviner’s mind is clearly not a terrific place for women. The women are engaged in pointless, ritualized activities–some are laboring to no obvious end; some involved in vague but obviously twisted and ungratifying sexual acts–and one senses they’ve been driven mad by the senselessness of the demands placed upon them. Here, by the way, is one of the original 19th Century German engravings by Antoine Ignace Melling upon which the work was based:

And I see in Eviner’s response a reproach: You Europeans might think this looks exotic and colorful and oh-so-Oriental, this harem-in-Constantinople business, but let me tell you, it’s not so exotic when you’re trapped in it.

So, that’s Turkish art today. Or one work, anyway.

It’s Sisyphean!

James, thanks for the name of the exhibit–Glitter and Doom–I was going mad trying to recall it!

I’m no art connoisseur, but my first impulse was to compare Weimar art to an earlier German painter whose works I admire: Caspar David Friedrich.

Art both reflects and affects any culture. The loss of ideals like order and beauty in artistic movements does signify, I believe, cultural corruption.

Absence of color does not alone make art depressing, forboding or ugly. But color can make all the difference.

That Melling piece strikes me as a middle ground between hope and despair. The subject matter might not be beautiful, but the subject is represented with appreciation for symmetry and color.