Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

The Emperor’s New Mind

The Emperor’s New Mind

Mathematical truth is not a horrendously complicated dogma whose validity is beyond our comprehension. -Sir Rodger Penrose

The Emperor’s New Mind is Sir Roger Penrose’s argument that you can’t get a true AI by merely piling silicon atop silicon. To explain why he needs a whole book in which he summarizes most math and all physics. Even for a geek like me, someone who’s got the time on his hands and a fascination with these things it gets a bit thick. While delving into the vagaries of light cones or the formalism of Hilbert space in quantum mechanics it’s easy to wonder “wait, what does this have to do with your main argument?” Penrose has to posit new physics in order to support his ideas, and he can’t explain those ideas unless you the reader have a sufficient grasp of how the old physics works. Makes for a frustrating read though.

What defines a sufficient grasp of physics depends strongly on whether or not you are mortality challenged.

The trouble is that even when you’ve done it that way you’re going to miss antecedent arguments. In his chapter discussing the lifetimes of black holes (it involves a lot of just sitting there) he makes an argument about the nature of phase space, which refers back to a theorem he introduced in his review of mathematics. But he offered no proof of the theorem. Was the review not thorough enough? To be thorough enough he’d have to give you the whole education, and you’d walk out of this book with at least a pair of bachelor’s degrees. And, let’s be honest, Penrose makes a better researcher than professor. His ideas are top notch. His explanations of them could use some work.

Knowing the impossibility of covering all the premises, and that I’m writing a Ricochet post and not a tome myself, I’m going to run through the argument backwards here, starting with the conclusion and then describing the antecedents that you need to make it work. I implicitly cede the ground of persuading you that it’s true, but that’s fine, because I’m not persuaded myself. I hope it makes for a cleaner understanding of the argument.

A computer program on a silicon wafer will never be intelligent in the same way that a human brain is.

That’s his conclusion right there. So far so good. That’s the premise for the book, if I didn’t want to hear about that I wouldn’t have picked it up in the first place.

To understand that, we need to know how a human brain’s intelligence differs from that of a computer program. A human brain is conscious, and a computer program is algorithmic.

Okay, we’re going to need to know what algorithmic means, and we’re going to need to know what it means to be conscious. The first is easier to define than the latter. A process may be said to be algorithmic if you can reach the conclusion of the process by means of a well defined series of steps. If you follow the rules for doing long division correctly you’ll get the correct answer, even if you’re not thinking about it particularly hard. Computers are algorithmic; physically you’ve got a lot of transistors switching on and off.

A heap of transistors turning themselves on or off turns a binary 0011 into the number three on your digital watch. Neat!

Consciousness is a non-algorithmic process.

Okay, that one’s a leap, and Penrose identifies it as such in the text. One of the major problems in this whole debate is what exactly it means to be conscious; the word remains in a “I knows it when I sees it” category. But let me back the argument down one more step before I keep going.

There exist non-algorithmic processes.

Wait, what does that mean, exactly? A process is non-algorithmic if there’s no algorithm we can use to get a correct answer. That doesn’t mean we need a good algorithm, or an algorithm that’ll even get the job done in any sort of practical time frame, but that in principle there exists a predictable way to get at the answer. Take password cracking as an example; a brute force attack (guess every possible password until you hit the right one) works, even if in practice it’s infeasible to guess a long enough password. On the flip side, what if you only get ten guesses and have to stop? The FBI ran into that problem with the terrorist’s iPhone after he died in the San Bernardino attack. There’s no process you can use that will guarantee a correct guess within the first ten attempts. (The FBI eventually got the phone unlocked, but though they won’t say how I can almost guarantee it wasn’t by guess and check.)

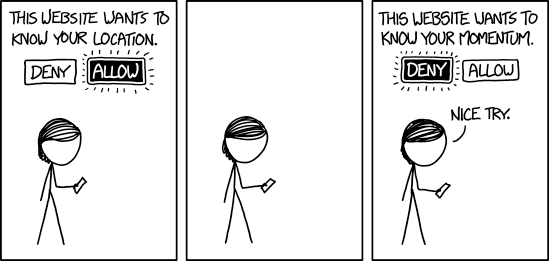

For more discussion of what’s an algorithm and why, please click on the picture. It’s not even a RickRoll!

The book’s primary example of a non-algorithmic process is the halting problem. A Turing machine (you could read “Turing machine” as “computer program” if you’re unfamiliar with the concept) may or may not stop. If you’ve ever watched that little hourglass turn itself upside down just hoping that you’ll get a chance to save your work before everything goes kablooie then you can understand why the halting problem is important.

It can be proven (it is proven in the book; I don’t intend to go all the way down the logic chain here) that there’s no general solution to the halting problem. But sometimes we can look at a program running and tell that it’s not going to stop. Does that mean that we have a better algorithm in our brain, one that detects stalled processes where our computers don’t, or does that mean that our brain is doing something else?

This also relates to Gödel’s incompleteness theorem, also discussed in the text. Gödel proved that, for any set of axioms, there exist true propositions which nevertheless can’t be proven by means of those axioms. But the proof relies on the use of intuition to observe that something which is obviously true is in fact true. Does the fact that we see that imply the brain isn’t just a computer running on neurons rather than transistors? That depends on how a brain works, doesn’t it? We’d better look at the other half of the proposition.

The brain may function on non-computable principles

Penrose is explicit in saying that certain functions of the brain, things like intuition and insight, are what define consciousness, and that they aren’t algorithmic processes. But to say that he needs to come up with a mechanism in the brain that allows our protoplasm to solve non-algorithmic problems.

Here Penrose is on as shaky ground as anywhere in the argument. You can tell he’s less confident talking about brain structures than he was about quantum mechanics, though I don’t think we can blame a physicist for that. But even if he was dogmatically correct on all the points of brain architecture as it was known to science, this book is thirty-some years old now. I do not believe the science has stood still in that time. Penrose identifies the growth and retraction of certain nerve connections as a potentially non-algorithmic process which could be a basis for consciousness that’s fundamentally different from the Turing machines you’re reading this on.

As an aside here, his description of chess programs is still accurate. Though the year 1989 did not yet have programs that could beat grandmasters and today I can go onto YouTube and watch a machine-learning program pants a traditional chess program (which in turn can outplay any human) the essentials of the argument hold up.

Penrose has to posit new physical theories in order to allow his brain’s nerve growth to be non-algorithmic. Almost paradoxically he’s on firmer ground when he does so. Penrose is an independent thinker and a career physicist and mathematician. If you asked me to list of the people on the planet most likely to revolutionize physics his name would be at the top of the list. (Perhaps not anymore; the man’s ninety. He has my permission to retire.) Penrose proposes that a new theory of quantum gravity may be coming, which in addition to resolving the conflict between relativity and quantum mechanics (the two great theories of the earlier part of last century) will resolve the hazy border between classical and quantum mechanics.

Let me just pause for a moment on that. According to the standard quantum theory you have a particle, and that particle has a wave function that describes it. The wave function evolves in a perfectly predictable manner until you measure it, in which case it collapses from a range of probabilities into one actuality. At which point the wave function starts evolving again. But what does it mean to take a measurement? At what point does a quantum level particle say “Oops! Light’s on! Everyone act normal.”?

Penrose posits a future physics where the difference between the quantum and the classical world depends on gravity. Once a quantum effect gets large enough, affecting enough mass, that (quantized) gravity jumps from zero to one unit then the wave function collapses and one probability is selected out of those available. Really, the bulk of the book is background so you can make sense of how that’s all supposed to work.

Now, we’re ready to march back up the logic chain. If there exists a future physics with (as he asserts) non-computable aspects, then perhaps that future physics explains nerve connection growth, and perhaps that allows the brain to manage things like flashes of insight, things that plodding, algorithmic silicon seems unlikely to produce.

Perhaps.

Actually, I find his ideas about where physics might lead to be plausible. Certainly the idea of quantized gravity leading to the collapse of wave functions is elegant enough that it might very well be true. As to the actual structures of the brain, maybe I’m being too harsh. If Penrose came from a physics background, well, so did I, and he at least did his homework on this stuff. Really his best evidence for his view comes from the nature of insight, and surely the assertion that it can’t be produced by any sufficiently complicated algorithm is as plausible as the assertion that it can because we simply don’t know what insight is or how it happens.

It takes four hundred and fifty pages to get this far. Along the way Penrose manages to hit on just about every topic in physics and mathematics. (I think he missed topology, but I’m not positive.) I find myself reacting to the book much like I did to Moby Dick; it’s a great opportunity to learn something, so long as you’re not too specific about what you’re learning. If you just let the whale take care of itself and you sit back and enjoy the essays on the whaling trade you can have a good time with that book. If all you want is the action, well, prepare to skip a number of chapters. And if you’re in it for the sea shanties I’ve got the hookup right here:

Was this book what I was looking for? No, not really. It is my conviction that the nature of the human brain builds certain blind spots into our perception of reality, and that any true picture of the world and how it works requires us to at least try to peek around the edges of those blind spots. I came in looking for evidence either for or against that position, and to see if I could infer some of the limits of those blind spots. That’s not what I found here. But if I did not read what I wanted to know, I read plenty that I ought to know.

Published in Science & Technology

Thank you for this excellent summary of a very complex work. I read it 30 years ago, and it was a slog. But, in the end, I found it rewarding.

The conclusion also fits my own personal bias that there is something more to human consciousness than what a computer can do. I think that Penrose is pretty convincing on that point. As you point out, he is weaker on exactly why that would be the case. He did write a sequel, Shadows of the Mind: In Search of a New Science of Consciousness, and I did read it, but it did not make the same impression on me as The Emperor’s New Mind.

As far as machine consciousness goes, I would not be surprised to see a point where a machine passes the Turing Test (gets someone to believe it is a real person) just through shear computing power. As I understand it, current natural language and language processing algorithms aren’t that different than the ones being developed in the 1980s, but we now have the computing power so that they do there job in real time. So perhaps someday with the whole ball of wax.

I read this book decades ago. Penrose is obviously brilliant. Yet, despite the technical fireworks, I left with the impression that Penrose had missed the forest for the trees.

It seems to me that what is significant about consciousness has nothing to do with whether its operations can be captured in an algorithm. What consciousness does is provide meaning to those steps. For instance, in your picture above of the LED-generated number “3”, it’s only a number because we say it is. Otherwise it’s just electrons flying around.

This is, I think the Chinese room objection to the Turing test. Supposing I have a computer terminal. I can type in “Hi! How are you?”, wait for an appropriate interval and get back the answer “I’m fine, thanks for asking.” Is it an intelligent machine?

Suppose that behind the terminal there isn’t a computer at all; it prints out a bit of paper tape with the symbols “Hi! How are you?” on it, and a man there reads it. Now, this man is Chinese, and he doesn’t understand my English letters at all, but he’s got a large catalogue of questions and answers, all in alphabetical order. He looks up my question, associates it with an appropriate reply, and flashes it back. But did he understand it? Not at all; he doesn’t speak English. I think this is also what Clavius is driving at when he describes computers being able to pass the Turing test through sheer computing power.

Two quick asides; in the original Chinese room thought experiment the philosopher who posed it (I forget his name) was in the room, and the questions were passed in and out in Chinese. I reversed it here because, much like the philosopher, I don’t speak Chinese. Also, if you want a dramatization of this effect you could do much worse than this one from Terminator 1, which I’m leaving behind a hyperlink because it’s not CoC compliant.

In a broader sense, I think Penrose has to take the line he does because he’s presupposing a materialist worldview. If humans are just meat robots then the default assumption has to be that the brain can be duplicated by a sufficiently complicated Turing machine, because that’s the simplest explanation for what we see. Penrose is arguing into non-computable, quantum mechanical new physics brain action because he may be unwilling to accept the existence of non-physical phenomena such as a soul which is driving the seat of consciousness. (I don’t know his personal views on religion, that just seems like a reasonable read based on his book.)

Thinking up another thought experiment here. Let’s say that I’ve got a time machine. After doing all the usual tourist stuff like killing Hitler and making a killing on the stock market I settle down to trolling historical figures for my own amusement. I set up a chess by mail game with Paul Charles Morphy, one of the greatest minds of Chess from the latter half of the 19th century. Morphy sends me a move, I feed the move into my modern day can-beat-any-grandmaster chess engine, it spits out a move and I post it back to Morphy. Two weeks later I get Morphy’s next move, cackling madly at him playing a foe he cannot beat.

Now let’s eavesdrop on a conversation between Morphy and a friend about the play style of this unknown opponent. Would Morphy have figured out that he’s up against a machine? Almost certainly not; his 1860s worldview wouldn’t include the possibility that there’s anything else for a Turing test to be performed on. He’d almost certainly tell you that it had sharp tactical play, and a fiendish ability to anticipate lines playing out many moves ahead. He might criticize it’s opening theory as being unsound, but that would be a flaw in Morphy’s theory, not the machine’s. He’d probably call the machine brilliant.

Would he call it inspired? Would he take the motions of a machine and, not understanding he was describing an automaton, attribute to them artistry, or merely skill? I don’t think the answer to that question is obvious either way. It’s at least plausible though that Morphy would attribute things like wit that are (insofar as we can tell) characteristic of natural intelligence to this machine. The chess program would pass that Turing test, which indicates a problem with the Turing test, not that the program is intelligent. Which in turn seems to indicate that we can’t determine consciousness by hard and fast rules. If there are no algorithms to detect a non-algorithmic process then, well, it takes one to know one.

And I don’t think this whole discussion is all that necessary spell out, I just like the idea of pranking Morphy.

I think chess is a bad example here because computer’s success at mastering chess (which has a deterministic set of rules) is not a good measure of consciousness. So Morphy thinks it’s a person. In his time it couldn’t be anything else. And nothing was exchanged that would be an indication of consciousness.

Exchange poetry? Perhaps a better thought experiment.

My smartphone can do everything arch-materialist philosopher Thomas Hobbes thought a conscious person does with information. All that information taken in–light waves, sound waves, touch. With an extra hardware doohicky and an app and some bluetooth, it could track chemicals in the air and chemicals in liquid to approximate smell and taste.

But it’s not aware of anything it processes.

Hobbes is wrong; Descartes is better.

In the novel Diamond Age one of the main characters is stuck trying to determine whether or not she’s taking with a machine; she writes him a love poem which he completely fails to interpret, which leads her to believe he’s actually a robot. Given the way that men and women interact I’m uncertain that your standard issue male would pass. (Or perhaps the reverse of that test. Yeah, she’s totally into me.)

But the point isn’t that Morphy would never expect a Mechanical Turk, it’s whether or not he’d read into the moves of a machine abilities which indicate not just mathematical skill but also artistry and flair, things which he’d read as consciousness which we would know it didn’t have. The question isn’t whether or not we could trick Morphy, it’s what he’s seeing as we do. Does he see spirit in his opponent’s moves, or is it somehow lifeless?

Back in my day, in the prehistoric faded mists of antediluvian time, the go-to text that held the torch of AI skepticism was Hubert Dreyfus’s What Computers (Still) Can’t Do. It was an easier read than Penrose, and had a simpler argument: Don’t even waste your energy proving that machines can’t be conscious. They are so far from consciousness that it’s like talking about how tall a tree it takes to reach the Moon.

Dreyfus’s long-lived academic popularity was probably boosted because academia yearned for an argument for human exceptionalism that wasn’t religious. Another factor was Dreyfus’s feisty, peppery sarcasm towards his opponents, which was entertaining but ultimately cheapened his work and turned those opponents into enemies. He relished being the AI’s world’s self-appointed scourge, equivalent to Professor Wormstrom, Dr. Farnsworth’s eternal rival in Futurama. And at the time of the first edition in the early Seventies, it was easy to sneer along. AI had promised plenty since Dartmouth and CMU in the late Fifties, and every real-world prediction looked like a joke. Self-driving cars? Continuous voice-to-text translation? Language translation? Photo pattern recognition? They didn’t happen.

Back then, that is. In the past twenty years we’ve reached those mileposts without much obsessing about the problem of consciousness. AI isn’t measured by consciousness as much as by. “would this task require intelligence if a human did it?”

When the wise guy gets his comeuppance, people tend to laugh, and they’re laughing at Dreyfus. Interestingly, though, even he didn’t claim that it was impossible, in theory, for a machine to be genuinely intelligent, just that nothing presented to him at the point was remotely up to the task.

And as you said, that is the limit of the Turing test.

It makes me think of the Star Trek TOS Episode What are Little Girls Made of? Dr. Roger Korby, who has found a way to transfer his consciousness into an android, tries to prove his humanity at the end of the episode:

But he cannot feel.

This is a great counter argument to my suggestion of poetry. Women are from Venus, men are from Mars.

Everybody knows SF examples of “strong AI”: HAL 9000 is one, a conscious machine that is effectively a disembodied person. Examples of “weak AI” include conversational fakes like ELIZA, which is pretty close to a Chinese room solution. ELIZA has a number of cleverly vague or Delphic responses triggered by key words and context.

I’m curious/fascinated by rare, in-between cases, of an artificial intelligence that has roughly the consciousness of an intelligent dog. It’s actual consciousness of a genuine sort but it ain’t human.

Not a great example, but hey, it’s at hand: The Forbin Project. Nobody’s idea of profound SF, but it had at least one interesting idea. Their HAL-like AI villain, Colossus, doesn’t immediately have consciousness but seems to work up to it as the story progresses.

From those who’d like to tell me that the mind is reducible to matter, I’d like a definition of matter that has anything–anything at all–to do with consciousness. Sentience, awareness–I know what that is.

I know what it is to take up space, or to be made of particles and energy. My teacup does those things. It’s not conscious. It has nothing to do with awareness; and yet we’re supposed to believe that you can bridge the infinite gap just by adding more? What a packet of ramen noodles has to do with the definition of a triangle, I have no idea; but assuming that the former creates the latter makes about as much sense as assuming that matter produces consciousness.

Probably not my best work, this is in the early era of my YouTube work when I had not yet learned to smile while on camera:

Ah, ELIZA. Written in LISP. It was on the open access Dec-10 at UCLA in 1979. We would access the machine from a Dec-Writer, a 132 column typewriter style machine that you would connect to the computer by dialing the phone by the back of the machine. I had an hilarious conversation with ELIZA when I started out by answering her question “What can I help you with?” by responding “I have no brain.” The dialog was great: “So what about not having a brain is bothering you?” etc. I had the printout for years but lost it.

Colossus: The Forbin Project was a very memorable film from my youth. I saw it when I was in Okinawa and the base I was on charged kids 25¢ for a film. My friends and I watched it many times in its short run at Camp Chinen. As I recall, Colossus gains consciousness gradually as you say, and then starts taking over when it finds “There is another system!” They, of course, merge and take over the world. Sorry about the spoilers, I doubt anyone will mind.

BTW–Damn, St. Augustine, that’s a righteous beard. I’ve been letting one grow for the first time in my 68 years, a Quarantine Quirk that I’ll probably shave soon. My kindly wife says I’m starting to look like Commander Riker. But I know the truth. I look into the mirror, and Burl Ives is staring back.

Okay, back to the riddle of consciousness.

Working in Pakistan at the time; what choice did I have?

This puts most things into view for me. I’ve been thinking mechanistically. Moving past the physical into the metaphysical, when Adam was created, God breathed breath or spirit into Adam, and became a living soul. The spirit from God, “breathed” out from God and into the lifeless clay, imbued it with life; and once embodied, the enlivened two (or at least the spirit) became two things: living; and a soul (and – it being enlivened by the breath of God – immortal).

This goes along with a kind of experience I’ve read of more than once. The type follows a particular pattern, people permanently ill beyond the ability to think or speak, have a moment or a few of lucidity at the time of death. One anecdote involves an old woman, who had been for a long time demented beyond speech or consciousness, and immediately before death spoke at length lucidly and clearly to her daughter, and then died. Some of the doctors insisted that this was impossible, but like so many things, what is perceived as the impossible is often possible.

It’s as if the mind is confined to operating through the brain, and in the last seconds when the diseased the brain is gone, the soul is momentarily freed.

This post has dredged up my summer session class in Existentialism. This was 40 years ago, so forgive any inaccuracies. Or better yet, correct them.

There are two types of conscious being: Being in itself and being for itself. Being in itself is us when we are dedicated to a task and just working away, unselfconsciously. Being for itself is when we are conscious of ourselves as a consciousness. Think of a keyhole peeper. Looking in, focusing only on the scene in the room he sees, is being in itself. Suddenly, there is the sound of footsteps behind him, he is seen! He is now totally conscious of himself as an independent actor, responsible for what he is doing.

Would a machine ever have that sense of reality? Of self? Or would they be locked into a being in itself mode with no knowledge of themselves as an independent actor?

I am also reminded of the movie The Mind of Mr. Soames (1970). Also an Okinawa movie for me. Mr. Soames is brain damaged from birth but is healed when he is 30. He goes through a childhood at 30. All the machinery of adult consciousness but none of the training. What happens to our computer when it suddenly realizes it’s in control?

When I was visiting my step-father about 7 months before he died, he was rapidly declining. We needed to help him down the few stairs in the house and conversation was repetitive and limited. One night while I was there, he showed up at my bedside, moving without trouble and speaking clearly about not particularly rational concerns. His physical control problems were gone. His speech was focused and clear. We got him back to bed and it was back to normal the next morning.

What happened that he could be beyond all of his apparent feebleness in the middle of the night?

Daniel Crevier’s AI: The Tumultuous Search for Artificial Intelligence (IIRC) has a section on “frames”, roughly meaning frames of reference. The keyhole peeper example would be a good one: the observer realizes that he’s now the observed and the frame of reference shifts. In effect, he shifts from being on the offense to being on the defense.

Yes, indeed. And he shifts from being just a conscious being into a thing, a “keyhole peeper,” changing self-perception too.

This makes me think of the art of medicine, cookbook medicine and telehealth (which will soon be integrated with cookbook medicine and AI, I’m sure). A doctor went in to see a patient, and asked how she could help him. He looked at her and said, “I’ve lost my words.” She asked this way and that, to find out what he meant, and he could speak in full sentences, but all he could really do to explain his predicament was say, “I’ve lost my words.”

So she ordered a CT and it showed a large brain tumor. I’ve wondered how a computer, either AI or simple algorithmic — ask this, and if this answer then ask this other thing — would have dealt with this man.

Actually, I could see a machine being able to do that. “Expert Systems” was one of the paths back to relevance for AI after “AI Winter” in the Seventies, when funding dried up. We’d define expert systems as merely a series of Horn clauses–if x is true, do this; if X and Y is true, do that. Clever algorithms apply those clauses and prune the decision tree so quickly it feels like you’re getting the benefit of an expert person. But it depends on restraining the situation. The machine can’t easily deal with anything novel, that can’t be sifted through sorting.

Early AI (Expert Systems in the vernacular of the time) was very successful with diagnosis for typical problems but failed on the edge cases. This is probably true for human doctors too. It takes insight to solve the tough cases. I recall a friend saying to me that doctors are just like mechanics. They look at how things are behaving and apply the remedy that worked last time or is indicated from their training. It is the former that adds to learning and a better doctor, as they try things and see how they work. The down side is that we are subjects of the training.

One other comment on Expert Systems. In the late 1970s, early 80s, DEC had system configuration experts order all the parts and determine how a system would be configured for a customer. DEC decided to build an expert system to do the configuration, so they interviewed the configurators and captured the rules. Once implemented, the results were most noted in maintenance. The humans kept trying new things so when maintenance came they had to figure out what was done and why. The machine did everything the same way every time, reducing maintenance confusion and costs.

Which was better? For computer configuration, the latter. For my health, I’d prefer the intuition of a human.

That’s funny, we were writing similar posts at the same time.

My personal definition of intelligence is to take that which is known or observable and synthesize more new knowledge from it. Really good doctors can synthesize new knowledge from existing knowledge, and know its significance. I suppose you can do this in any field. I suppose AI can create new knowledge, or draw correlations and inferences, better than people, but can it know the significance of this new knowledge? Can it see its applicability?

That’s a great definition.

These huge inference engines can find hidden correlations. TrueCar decided that they will keep everything in a big Hadoop data lake. They wrote an engine over that data lake that would look for correlations. The staff got silly when the CIO said everything and anything goes in the data lake. One staffer started putting MLB stats, schedules, and results into it. The engine found that they should not refer a customer to a dealer located near an MLB stadium during a game. Not knowledge, but operationally valuable. Also, not new knowledge.

I don’t think AI can “know.” So knowing the significance is moot.

These machine learning algorithms are optimizing for certain outcomes. You have training data to do so. And it takes a lot of data. Google’s algorithms (machine learning models) are bases on billions of data points. So only at the tech giant scale can you really machine learn.

And if anything will become SkyNet, it will be Google.

You ever remember that you wrote the tags for your post late at night, but can’t recall what they were precisely?

Uh, me neither.

Tags? We don’t need no stinking tags…

Hospice workers have many many such anecdotes. Moreover, they report people holding lucid converse when no one else seems to be in the room, then relaying the subjects of those conversations to their friends and relatives, and communicating knowledge they could not have possibly had otherwise.

Something is directing and forcing a computer to make the yes-no connections from one silicon atom to the next. That something is human will. Artificial intelligence is not true intelligence. It’s not even a good copy. It can’t be. It is confined forever to being a product of the minds who programmed it.

AI seems intelligent–capable of figuring things out or making predictions or decisions–but it is never smarter than the human beings who told it to go to point B whenever it reaches point A.