Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

American Catholicism: A Renewed Call to Action — A Second Post Reposted

American Catholicism: A Renewed Call to Action — A Second Post Reposted

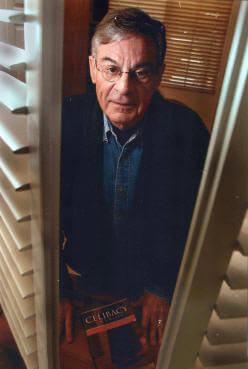

Six years ago, on 14 February 2012, I posted a piece on the state of the Catholic Church in the wake of the so-called pedophilia scandal. I regret to have to say that it remains pertinent now — one month after the death of Richard Sipe, the foremost expert on clerical abuse, whom I quote at length below. Most of the links are functional — apart from the one that once led to Sipe’s website, which can now be found at awrsipe.com. As Sipe put it 25 years ago, “The problem of sexual abuse we see today is only the tip of the iceberg. If we follow the problem to its foundations it will lead to the highest corridors of the Vatican.”

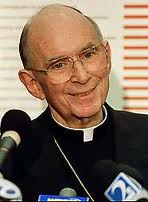

Last Friday, I posted on Ricochet a piece entitled American Catholicism’s Pact With the Devil. In it, among other things, I traced the crisis now faced by American Catholicism to the reign within the American Church of Joseph Bernardin, Cardinal-Archbishop of Chicago. In my haste, I got a detail or two wrong, and I was challenged not only with regard to the Cardinal’s cursus honorum but also with regard to the role he played in the scandal concerning the sexual abuse of children by Roman Catholic clergy. This post is meant to correct the record with regard to minor details, to flesh it out with regard to the profound damage done the American Church by Cardinal Bernardin, and to suggest that we might be witnessing a turning of the tide.

In doing so, I will draw on various sources. But let me say at the outset that the most important of these is the article The End of the Bernardin Era: The Rise, Dominance, and Decline of a Culturally Accommodating Catholicism published by George Weigel in February 2011 in First Things. Here, in Weigel’s words, is the pre-eminent fact:

In his prime, Joseph Bernardin was arguably the most powerful Catholic prelate in American history; he was certainly the most consequential since the heyday of James Cardinal Gibbons of Baltimore in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. When he was in his early forties, Bernardin was the central figure in defining the culture and modus operandi of the U.S. bishops’ conference. Later, when he became archbishop of Cincinnati and cardinal archbishop of Chicago, Bernardin’s concept and style of episcopal ministry set the pattern for hundreds of U.S. bishops. Bernardin was also the undisputed leader of a potent network of prelates that dominated the affairs of the American hierarchy for more than two decades; observers at the time dubbed it the “Bernardin Machine.”

Here are some of the details. Bernardin was born in 1928 in Columbia, South Carolina. He was ordained a priest for the Charleston diocese in 1952. His talents were recognized immediately, and he rocketed up the clerical ladder. He was a monsignor within seven years. By 1966, he was an auxiliary bishop in Atlanta. Two years later, he was named the general secretary of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops (NCCB), the forerunner of today’s United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB). The NCCB was at that time new; Bernardin was the very first to serve as its general secretary; and he was one of the two men who shaped the institution – which to this day formulates policy for the American bishops.

Here are some of the details. Bernardin was born in 1928 in Columbia, South Carolina. He was ordained a priest for the Charleston diocese in 1952. His talents were recognized immediately, and he rocketed up the clerical ladder. He was a monsignor within seven years. By 1966, he was an auxiliary bishop in Atlanta. Two years later, he was named the general secretary of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops (NCCB), the forerunner of today’s United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB). The NCCB was at that time new; Bernardin was the very first to serve as its general secretary; and he was one of the two men who shaped the institution – which to this day formulates policy for the American bishops.

In 1972, Joseph Bernardin became Archbishop of Cincinnati, and two years later he was named – at the ripe old age of forty-six – the presiding officer of the NCCB. In his years as an official of that body, he hired its staff, and he put his stamp on the organization. Moreover, for decades, the principal posts in the NCCB would be in the hands of Bernardin himself or of one of “Bernardin’s boys,” as they were called. His first five successors as presiding officer of the NCCB — John Quinn, John Roach, James Malone, John May, and Daniel Pilarczyk – were his nominees. Moreover, as George Weigel makes clear, the Bernardin era did not end when the Cardinal died of pancreatic cancer in 1996. In fact, it was not fully over until November 2010, when Archbishop Timothy Dolan of the city of New York was elected the presiding officer of the UCCB in preference to Bishop Gerald Kicanas of Tucson, who had started his episcopal career as one of Bernardin’s auxiliaries. As Diogenes at CatholicCulture.Org put it some years ago, “It is almost impossible to over-estimate the importance of Cardinal Bernardin to the U.S. Catholic Church; on that point his critics and admirers are unanimous. Like Bismarck or Stalin or Richard Daley, he created and presided over a bureaucracy whose impersonality became his personal tool, and the way the USCCB does business bears his stamp to this day.”

The church that dissolved in scandal in 2002 – when The Boston Globe began reporting on the sexual abuse of minors by Catholic priests and the protection provided the malefactors by Bernard Francis Cardinal Law of the Boston Archdiocese and his episcopal predecessors – was Bernardin’s church. As a member of the Congregation of Bishops in Rome, he played a decisive role in picking the American bishops and in determining their assignments. Moreover, his influence was dispositive for a long time in determining who would head the bishop’s conference, and it was under the Bernardin machine that the American church decided how it would handle the grave sexual abuse scandal that erupted in the diocese of Lafayette, Louisiana in the mid-1980s.

In the wake of that event, three individuals joined together – with encouragement from the Papal Nuncio and a number of bishops – to consider the problem of the sexual abuse of minors by clergymen as it applied to the American Church as a whole. The three were Father Michael Peterson, M. D, a psychiatrist who specialized in the treatment of wayward priests.; F. Ray Mouton, J.D., the defense attorney hired by the Lafayette, Louisiana diocese to defend a priest who had sexually abused eleven different boys; and Father Thomas P. Doyle, O.P. J.C.D., a canon lawyer attached to the office of the Papal Nuncio in Washington, D. C. The confidential report produced by this committee was a bombshell. It suggested that sexual abuse was quite common. It warned about the prospect of lawsuits and predicted that the American Church would eventually have to pay out more than a billion dollars; it firmly and fiercely denied that there was any possibility of curing those who sexually abused minors; it spoke movingly about the long-term damage done those who were sexually abused as children; it argued for an immediate suspension of clergymen who were accused; and it urged the bishops to weed out from the seminaries those likely to engage in such misconduct.

Peterson, Mouton, and Doyle hoped to have their report discussed in detail by the bishops at their annual conference, but Bernardin’s boys at the NCCB saw to it that the report was tabled. Some months later, Father Peterson, who would die of AIDS in 1987, sent a copy to every bishop in the United States. He received no response. When Father Doyle insisted on pressing the issue, he was dropped by the Papal Nuncio and treated as persona non grata by the American bishops. He ended up in exile as a chaplain on a military base in Greenland, and the problem was hushed up. It was thanks to the Bernardin machine that the bishops continued sending the perpetrators to psychological counseling and then dispatching them to new parishes or to other dioceses where there was no one who knew about their past. Bernardin and his boys did not invent the culture of clerical corruption. In full knowledge of what was going on nationwide, however, they perpetuated it.

In Chicago – where Bernardin became Archbishop in 1982 and Cardinal a year later – things came to a head a full decade before they did in Boston, and, in the face of the scandal, Bernardin was, as always, nimble and effective. When the lawsuits began, and the Cook County State’s Attorney Jack O`Malley turned a baleful eye on the Archdiocese, The Chicago Tribune reported that Cardinal Bernardin “defused a conflict” with the prosecutor by issuing a “20-page guideline” for the Archdiocese, which replaced “a priest-managed investigations system with a non-clergy ‘fitness review administrator,’” tasked with reporting priestly misconduct to the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services, and “a nine-member board … consisting of a nun, five laypeople and three parish pastors.”

To this day, Bernardin’s admirers cite this as a sign of his integrity and courage and of his eagerness to confront the culture of corruption. In fact, it was a species of “damage control,” and it constituted a confession that, ten years after Bernardin, a vigorous and effective administrator, had taken over the Chicago Archdiocese, its priests and their archbishop could not be trusted to deal with the sexual abuse of minors by the archdiocesan clergy. In this, as in other matters, Bernardin was the model for the other bishops. It was not until O’Malley began his investigation of the Archdiocese that Bernardin made these changes. He did not introduce them voluntarily. He did so under pressure. Had The Chicago Tribune and the other newspapers in Chicago been as diligent in digging up dirt as The Boston Globe would be a decade later, the scandal that ripped through the church in 2002 might well have begun in Chicago in 1992.

In 1993, Bernardin was himself accused of sexual abuse by a former seminarian named Stephen Cook, who was dying of AIDS. Bernardin fiercely denied the charge; the Vatican and many of the American bishops rallied in his defense; and the seminarian later dropped the suit. The public story at the time was that Cook then apologized to the Cardinal. But, in the keynote address that he delivered to the LINKUP National Conference held by the survivors of clerical abuse in 2003, A. W. Richard Sipe told a different story:

In 1993, Bernardin was himself accused of sexual abuse by a former seminarian named Stephen Cook, who was dying of AIDS. Bernardin fiercely denied the charge; the Vatican and many of the American bishops rallied in his defense; and the seminarian later dropped the suit. The public story at the time was that Cook then apologized to the Cardinal. But, in the keynote address that he delivered to the LINKUP National Conference held by the survivors of clerical abuse in 2003, A. W. Richard Sipe told a different story:

A sad, and as yet unsolved, chapter of the sexual abuse saga in the United States is the story of Cardinal Joseph Bernardin. This man probably did die a saint, as his close friends attest. Without doubt, he did many wonderful things for the Church in America.

In the media flurry that surrounded the allegation of sexual abuse, an impertinent reporter asked the Cardinal, “Are you living a sexually active life?” A simple “no” would have been sufficient. But the Cardinal said, “I am sixty-five years old, and I have always lived a chaste and celibate life.”

However defensible in the arena of public assault, I knew that the statement was not unassailably true. Years before, several priests who were associates of Bernardin prior to his move to Chicago revealed that they had “partied” together; they talked about their visits to the Josephinum to socialize with seminarians.

It is a fact that Bernardin’s accuser did not ever retract his allegations of abuse by anyone’s account other than Bernardin’s.

If, as reported, three million dollars were paid in handling the scandal, certainly there are still informed people in Chicago who know at least part of the story. And the story is complex. It holds repercussions far beyond Chicago and one allegation.

There are three reasons why we should not dismiss out of hand as malicious gossip Sipe’s euphemistically-phrased claims. The first is that what he reports with regard to the hush money purportedly paid the seminarian conforms to what was standard operating procedure in American dioceses at the time. The Boston Globe reports that, between 1992 and 2002, the Archdiocese of Boston secretly settled more than seventy cases of child abuse in this fashion. It would not be odd if this were done in Chicago as well. In fact, it is precisely what one would expect.

The second reason for taking Sipe’s claims seriously is the fact that what we know about the clerical sexual abuse of minors is entirely a consequence of the lawsuits brought against the church and the investigations undertaken by the secular authorities. Had it not been for these, the great game of shuttling the predators around would still be going on. There is no reason at all to accord the benefit of the doubt to the bishops. In and soon after 2002 we learned what accomplished liars they had been.

The third reason for suspecting that what Sipe reports might be right is that he is as well-informed an observer as we have. Richard Sipe is a former priest. He was a Benedictine monk for eighteen years, was laicized by the Vatican in 1970, and married. For a long period prior to his departure from the priesthood, he was involved as a psychologist in counseling priests who were having trouble leading celibate lives. He continued doing so after leaving the priesthood, and at various times both before and after he taught in Catholic seminaries. He has testified in case after case involving the sexual abuse of minors by clergymen. He has written a number of books on the subject, and he is a Catholic liberal sympathetic to the political stance of Cardinal Bernardin. I cannot prove that he is telling the truth, but there is no reason to think him a fabricator of lies. When he estimates that about 6% of the priests in the United States in the 1980s were guilty of the sexual abuse of minors and that two-thirds of the bishops had experience in shuttling these men around, his assertions are entirely plausible. The John Jay Report produced in 2004 for the Catholic bishops by the John Jay College of Criminal Justice of the City of New York indicates that, between 1950 and 2002, 4% of the priests in the United States were accused at one time or another of child abuse, and we can be confident that there were perpetrators who were never accused. Two-thirds of these allegations were lodged between 1993 and 2003. Prior to that time, shame on the part of the victims, fear of the fury that they would incur if they went public, and an ill-deserved respect for the hierarchy of the Church generally dictated silence.

As Diogenes observes, one of the major themes of Sipe’s ruminations is that we will never fully understand what happened if we do not attend to “the connection between the sexual misdeeds of churchmen in powerful positions and the cover-ups — personal and institutional — perpetrated by men they recruited, groomed, and promoted.” Here is the way that Sipe put it in his keynote address:

Why is the fight so furious? Why is the struggle to keep FACTS buried so vigorous? Important clues exist in the genealogy of abuse. I have been able to trace victims of clergy and bishop abuse to the third generation.

Often, the history of clergy abusers reveals that the priest himself was abused – sometimes by a priest. The abuse may have occurred when the priest was a child, but not necessarily.

Sexual activity between an older priest and an adult seminarian or young priest sets up a pattern of institutional secrecy. When one of the parties rises to a position of power, his friends are in line also for recommendations and advancement.

The dynamic is not limited to homosexual liaisons. Priests and bishops who know about each other’s sexual affairs with women, too, are bound together by draconian links of sacred silence. A system of blackmail reaches into the highest corridors of the American hierarchy and the Vatican and thrives because of this network of sexual knowledge and relationships.

Secrecy flourishes, like mushrooms on a dank dung pile, even among good men in possession of the facts of the dynamic, but who cannot speak lest they violate the Scarlet Bond.

I have interviewed at length a man who was a sexual partner of Bishop James Rausch. This was particularly painful for me since Rausch and I were young priests together in Minnesota in the early 60s. He went on to get his social work degree and succeeded Bernardin as Secretary of the Bishops’ National Conference in DC. He became Bishop of Phoenix.

It is patently clear that he had an active sexual life. It did involve at least one minor. He was well acquainted with priests who were sexually active with minors (priests who had at least 30 minor victims each). He referred at least one of his own victims to these priests.

What was his sexual genealogy? What are the facts of his celibate/sexual development and practice? Did those who knew him know nothing of his life? Perhaps so! But he was in a spectacular power grid of bright men. He was Bernardin’s successor at the US Conference. Bishop Thomas Kelly at Louisville was his successor. Msgr. Daniel Hoye and Bishop Robert Lynch, among others, took over his job.

Let me be perfectly clear. I am not saying or implying in any way that these men were partners in “crime” with Jim Rausch. But I am saying that anyone who sets out to solve a mystery has to ask people who knew the principal, “What, if anything, did you know or observe about the alleged perpetrator?”

After all, the Church’s hardened resistance to dealing honestly with the problem of sexual abuse on their own has compelled the civil authorities to move in, ask the questions, investigate allegations. The Church in America has been its own worst enemy – creating mysteries and doubts, rather than clear answers that inspire confidence.

Even bishops innocent of sexual violations themselves, by their silence, concealment of facts and resistance to effective solutions, choose to be part of a genealogy of abuse and reinforce a culture of deceit.

In this speech, Sipe does not use the phrase “lavender mafia,” but his focus is the network of powerful clergymen who protected the malefactors and allowed the seminaries to become brothels. As Diogenes puts it,

We don’t need to jump to a Grand Unified Theory of conspiracy in order to recognize corruption; ordinary self-interest can account for particular incidents of ad hoc collusion by which gay bishops who are sexually compromised take care of their own. By the same token, it is absurd to pretend that politically astute gay bishops in key positions of influence could have been unaware of the liabilities of the men they advanced, defended, and perjured themselves for.

To anyone who has paid attention to the major players in the Crisis, Sipe’s roster of Bernardin cronies is striking. For a glimpse of the Southwest Triangle (Rausch, O’Brien, Moreno) go here, here, here, here, and here. For Robert Lynch’s connections, go here and here. Thomas Kelly, whose archdiocese now has problems of its own, winked through Rudy Kos‘s annulment (in spite of his wife’s insistence he was a pedophile), clearing his way into the Dallas seminary headed by Michael Sheehan, who later became Archbishop of Santa Fe. A power grid indeed!

If you follow the links – most of which are still active – you will get the picture, which is in no way pretty. Too many of those who found their way into positions of influence and power thanks to the patronage of Cardinal Bernardin not only failed to honor the vow of celibacy they had themselves taken but were criminally lax in its enforcement. The effect was to foster a culture of corruption throughout the American Church and to dishearten those – whether homoerotically or heterosexually inclined – who were fiercely intent on honoring their own vows. It was in this context that the small minority who preyed on children were protected from the legal consequences of their crimes and allowed to continue. Bernardin and his proteges regarded the sexual abuse of children as a moral lapse comparable to clerical drunkenness.

It is, as I argued in American Catholicism’s Pact With the Devil, no accident that the prelates most responsible for the perpetuation of this vile modus operandi were also inclined to downplay the significance of Roe v. Wade, to divert the energy of the institutional Church into a struggle on behalf of the administrative entitlements state, and to discourage the clergy from addressing the challenge posed to Christian morality by the sexual revolution. Joseph Bernardin became the presiding officer of the NCCB shortly after the Supreme Court handed down its opinion in Roe v. Wade, and it fell to him to articulate the strategy that the Church with regard to that decision has followed ever since. As George Weigel intimates, it is a good thing that the Bernardin era has come to an end.

It is, as I argued in American Catholicism’s Pact With the Devil, no accident that the prelates most responsible for the perpetuation of this vile modus operandi were also inclined to downplay the significance of Roe v. Wade, to divert the energy of the institutional Church into a struggle on behalf of the administrative entitlements state, and to discourage the clergy from addressing the challenge posed to Christian morality by the sexual revolution. Joseph Bernardin became the presiding officer of the NCCB shortly after the Supreme Court handed down its opinion in Roe v. Wade, and it fell to him to articulate the strategy that the Church with regard to that decision has followed ever since. As George Weigel intimates, it is a good thing that the Bernardin era has come to an end.

One can only hope that Archbishop Dolan is up to the task of cleaning the Augean Stables built by Joseph Cardinal Bernardin. So far, he and his colleagues have done a better job than I realized when I posted American Catholicism’s Pact With the Devil. When I wrote that piece, I relied on the reports in the press concerning the letter that the bishops sent to President in response to his announcement that, in providing health insurance for its employees, the Church would have to provide contraception coverage and abortifacients. In reporting on the response of the Church, the press did not mention that the bishops had in their letter come to the defense of Catholic employers and that they had made the same point with regard to companies owned and operated by the adherents of other faiths. The fact that they did so on this occasion and that in response to the “accommodation” proposed on Friday by President Obama they not only stood their ground but reasserted the rights of everyone in this matter is heartening. I would like to think that this marks a turning point in the history of Roman Catholicism in America and that, under the leadership of Archbishop Dolan, the Church in the United States will relinquish its embrace of the administrative entitlements state, abandon the presumption to an expertise in political affairs that it does not possess, and take up the responsibilities that are its proper task.

One can only hope that Archbishop Dolan is up to the task of cleaning the Augean Stables built by Joseph Cardinal Bernardin. So far, he and his colleagues have done a better job than I realized when I posted American Catholicism’s Pact With the Devil. When I wrote that piece, I relied on the reports in the press concerning the letter that the bishops sent to President in response to his announcement that, in providing health insurance for its employees, the Church would have to provide contraception coverage and abortifacients. In reporting on the response of the Church, the press did not mention that the bishops had in their letter come to the defense of Catholic employers and that they had made the same point with regard to companies owned and operated by the adherents of other faiths. The fact that they did so on this occasion and that in response to the “accommodation” proposed on Friday by President Obama they not only stood their ground but reasserted the rights of everyone in this matter is heartening. I would like to think that this marks a turning point in the history of Roman Catholicism in America and that, under the leadership of Archbishop Dolan, the Church in the United States will relinquish its embrace of the administrative entitlements state, abandon the presumption to an expertise in political affairs that it does not possess, and take up the responsibilities that are its proper task.

In the Bernardin era, Catholic clergymen lost their way. On questions of faith and morals, they spoke in at best a muted fashion. On political questions beyond their ken, they ran their mouths incessantly. To professed Catholics who openly rejected the teaching of the Church on the pre-eminent moral issue of the day, they lent their support. Barack Obama has now shown them the price that they will have to pay if they do not radically reverse course. Maybe, just maybe, they will.

In the Bernardin era, Catholic clergymen lost their way. On questions of faith and morals, they spoke in at best a muted fashion. On political questions beyond their ken, they ran their mouths incessantly. To professed Catholics who openly rejected the teaching of the Church on the pre-eminent moral issue of the day, they lent their support. Barack Obama has now shown them the price that they will have to pay if they do not radically reverse course. Maybe, just maybe, they will.

In doing so, I hope that they take to heart an observation made by George Weigel in The End of the Bernardin Era: “The late Fr. Richard John Neuhaus used to say that, when the Church is not obliged to speak, the Church is obliged not to speak; that is, when the issue at hand does not touch a fundamental moral truth that the Church is obliged to articulate vigorously in the public-policy debate, the Church’s pastors ought to leave the prudential application of principle to the laity who, according to Vatican II, are the principal evangelizers of culture, politics, and the economy. The USCCB’s habit of trying to articulate a Catholic response to a very broad range of public-policy issues undercuts this responsibility of the laity; it also tends to flatten out the bishops’ witness so that all issues become equal, which they manifestly are not.”

I am struck by one fact. I wrote my earlier post in the hope that it might help educate Catholic laymen and clergymen with regard to their duty. It seemed an opportune time to point to the obvious – that the teaching articulated by Cardinal Bernardin and adopted by the American Church was not just pretentious and false but that, by undermining limited government, it posed a danger to religious liberty. Since writing it – especially since Rush Limbaugh read it out on his show on Monday – I have received innumerable congratulatory e-mails and telephone calls from priests, seminarians, and laymen from every corner of the land. Only one individual mistook my criticism of the hierarchy for an attack on the Church itself.

The proper response to criticism of the sort he articulated is the one which Winston Churchill voiced when he rose in Parliament on 5 October 1938 to criticize a Prime Minister drawn from his own party:

Our loyal, brave people… should know the truth. They should know that there has been a gross neglect and deficiency in our defences; they should know that we have sustained a defeat without a war, the consequences of which will travel far with us along our road… and do not suppose that this is the end. This is only the beginning of the reckoning. This is only the first sip, the first foretaste of the bitter cup which will be proffered to us year by year, unless by a supreme recovery of moral health and martial vigour, we arise again and take our stand for freedom as in olden time.

As one recent correspondent said to me in the course of reminding me of this passage, “The enemy of freedom is not always foreign and external.”

Obamacare delenda est!

ADDENDUM: If you find this of interest, you may wish to consult its sequel: More Than a Touch of Malice.

If you want to know why I added the word “Renewed” to the title of my original post, let me suggest that you read my recent post Prelates and Pederasts. The problem I identified still exists … first and foremost in Rome.

Published in Religion & Philosophy

I sometimes think Ann Barnhardt is a nut. But all that she says comes into the light. Listen to this podcast to learn about Bernardin. He was an evil man.

Link to the first post from last Friday doesn’t work

No saying she is a saint, but a lot of Saints were considered crazy or out there in their day. When going against conventional wisdom it is hard to get a fair hearing. It is hard for me to hear as well, but the truth hurts.

Try http://ricochet.com/archives/american-catholicisms-pact-with-the-devil/.