Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

How do Muslims in Paris View this Election?

How do Muslims in Paris View this Election?

Update: I replaced the original text with a corrected version, including Matthew’s own photos, which are much better.

Update: I replaced the original text with a corrected version, including Matthew’s own photos, which are much better.

Matthew Clayfield’s an Australian journalist I met when I lived in Istanbul. He does careful, serious reporting, and I’ve always thought it deserves more attention. But like most reporters, he’s caught between the old business models for journalism (which are dead) and the new ones (which are at last struggling to be born, but we’re still trying to figure out how to make them work). So chances are, you haven’t yet read his work.

This week, he’s been in Paris to cover the election. I haven’t seen him yet. We exchanged a few messages on Facebook late last night and quickly agreed we’d both rather get some sleep than see each other, even if we’re rarely on the same continent, no less in the same city.

He told me (before he crashed) that he hadn’t been able to find an outlet to publish an article he’d just finished, one about an obviously interesting question: How do Muslims in Paris view this election? I read it and found myself terribly frustrated that he couldn’t sell it. It shouldn’t go to waste. He‘s not here on an expense account, and Australia isn’t exactly a bus ride away.

Like I said, there are still a few kinks to work out with these new business models.

So I asked him if I could publish it here. He kindly agreed. And thus today, for a change, instead of hearing me ask you to fund my reporting, you’ll hear me ask you to fund his. You can do that on Patreon.

So I asked him if I could publish it here. He kindly agreed. And thus today, for a change, instead of hearing me ask you to fund my reporting, you’ll hear me ask you to fund his. You can do that on Patreon.

I’d love to talk to him about how he’s been, and the state of the world, and how Patreon’s working for him so far. But I’m not sure we’re ever going to get a chance to sit down and compare notes, because of course today we’ll be writing our post-election pieces — and tomorrow we’ll be pitching them to editors, and ideally, selling them, too.

(Some of you just did a double take.) “You’ll be doing what, Claire?”

Good question. I’m going to let you in on a little trade secret. You may not realize this, but every piece you’re going to read later today about how this election turned out is being written, right now, by journalists who don’t yet know. Think about it: Because of the blackout — which I explained a bit in this comment — we won’t even see exit polls until 8:00 p.m. (although Swiss and Belgian outlets will leak them earlier). Most regions will have reported by 10:00 p.m.; soon after that, the official results will be published on the French Interior Ministry website. Then — literally within minutes, as you’ll see — hundreds of fully-formed, 1,200-word articles that tell you what the results mean will spring up like gazelles all over the international media.

But of course (and this is obvious when you think about it), no one can write that fast. So we write them in advance. The way we do it is we write several pieces, reflecting the various plausible outcomes — in this case ranging from “Stunning upset,” to “Macron wins but not by as much as expected,” to “Macron wins in modern history’s biggest landslide” — and we structure them so they can easily be updated or reworded depending how the details shake out. We leave space for the vox pop quotes that we’ll scramble to find later tonight or in the morning, depending on the publisher’s time zone.

So I may not get to see Matthew on this trip at all, which would really be a shame. But at least you’ll get an introduction to him.

*******************************************

In the courtyard of the Grand Mosque of Paris, where the emerald green tiles of its dormant fountains dry quickly after the afternoon rain, Dalil Boubakeur is helped by his assistant to the garden’s sunken war memorial. He lays a wreath, the imams sing, and officials, ambassadors, and the rest of us, look on.

The president of the French Council of the Muslim Faith and current rector of France’s first mosque is here to commemorate the 72nd anniversary of the end of the Second World War in Europe. He’s a few days early, but hey: the actual anniversary coincides with France’s most important election in a generation, if not since the war itself, so give the old man a break. He’ll look upon you as an old friend, realise you don’t speak any of his languages, and still give you a handshake or a hug. Anyway, tomorrow’s Friday, and Friday prayers are of the utmost importance. In this day and age, in this age and climate, they should take precedence: it’s a matter of principle.

See Matthew’s video:

We retire to an antechamber where old men in old uniforms take their seats in front of plates of baklava. The oldest among them rises with assistance and takes his place behind the lectern. He begins and ends by emphasising the various roles played — and ultimate sacrifices made — by French Muslims in the liberation of Europe and North Africa from Nazism.

Actually, the entire mosque is a kind of war memorial. It was founded in 1926 out of respect to the “Musulmans” who laid down their lives for France in WWI. When Boubakeur addresses the gathered dignitaries, he makes sure to press home the horrors of the Holocaust as well: it was here, after all, within the mosque’s walls, that his predecessor, Si Kaddour Benghabrit, ran a secret refuge for Algerian and European Jews during the Occupation, often providing them with fake Muslim birth certificates. The Grand Mosque was Grand Central on the underground railroad.

But times change. The country of the Dreyfus affair is now that of Marine Le Pen, the Front National, and their supporters. It’s the country of Le Pen’s stunning run at the presidency. This is where we’re at now. C’est la vie.

Like the polls and the pundits, Boubakeur doesn’t think Le Pen will win when the results start coming in later today. But given a push, and asked to imagine, the old dog knows exactly how to bark.

“It would be like an atomic bomb falling,” he says. “It would have the same effect, especially on the Muslim community. If such a thing was able to occur, it would be like [Emmanuel] Macron says. It would signal of the start of a civil war.”

“Well,” he shrugs diplomatically, “probably.”

Of course, Ms Le Pen would argue that the war has already begun. In the most acrimonious exchange of her rather acrimonious final debate with Mr Macron on Wednesday, the former leader of the National Front — she temporarily stood down after the election’s first round in attempt to get past the party’s divisive brand — Ms Le Pen accused her opponent of being “indulgent with Islamic fundamentalism”. He accused her in turn of selling the French people “snake oil”.

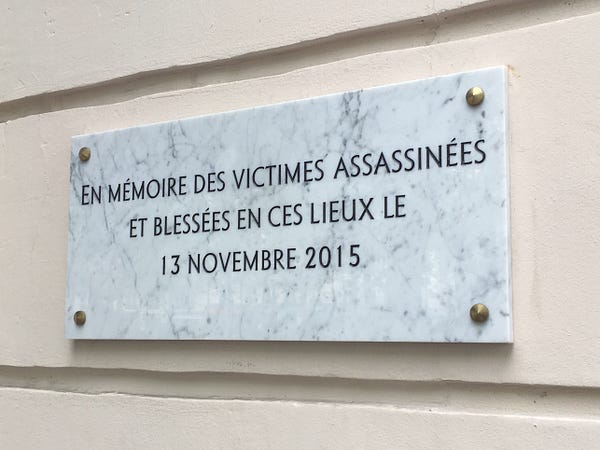

It takes less than an hour to walk from the Grand Mosque to Masjid Omer, or the Mosque of Omar Ibn Al Khattab, in the 11th arrondissement. The walk takes you past both the Place de la Bastille, where another, bloodier change in leadership once took place, and the famous-for-all-the-wrong-reasons Bataclan, where on November 13, 2015, three gunmen killed ninety people and injured countless more in an attempt to put the city of lights out for good. It reopened last year, on the eve of the attack, with a performance by Sting and a plaque commemorating the attack. A graffito on one of the doors — it would be nice to think that it’s been there since the violence and has been left there as a memorial of its own — urges pedestrians to “Fuck ISIS”.

The attack on the offices of the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo had occurred only ten months earlier. The brains behind that bloody operation are said to have attended Masjid Omer, where a deeply conservative but avowedly apolitical version of Sunni Islam, Tablighi, is preached. They didn’t go there often and apparently missed the apolitical bit. Masjid Omer was and remains under close observation by France’s General Directorate for Internal Security.

It’s a nondescript building in a part of town that demands at least a little description. It’s one of those places where the hyphen in “bourgeois-bohemian” doesn’t denote a compound term so much as manifest a class divide. Gourmet butcher shops brush up against workers’ bars and those against drunks yelling at other drunks for dropping the mattress in the doorway wrong. I’m pleased to note that it’s right next door to École Saint-Paul until I learn that École Saint-Paul is a private school where well-meaning well-to-do types send their kids in lieu of the public one on the far side of the park up the street from the mosque.

Sarah, 29, is sitting in the park in question with her two young children. An Algerian permanent resident in the country — unable to vote, but married to a French-Algerian who can — she’s worried about what might happen should Ms Le Pen come to power.

“Of course I’m afraid of her,” she says. “The election has caused a lot of tension and she will make the situation worse. People like me will lose their nationality. She is Trump à la française. She will divide us”

But for Sarah, the tension between France’s fiercely-guarded secularism and her fiercely-guarded religious beliefs existed long before the latest boom in nativist populism here and elsewhere. For her, it all comes down to one issue: the veil. (Sarah uses the term in a way not always understood by Westerners: she’s wearing a hijab, which “veils” her hair, but not her face.) A banker in Algeria, she had to qualify all over again when she arrived her adopted country, only to be told that she wasn’t allowed to on the grounds that the school had a policy about her headgear.

“I would love to work in this country,” she says. “I have a friend in Germany who goes to work every day in the veil and it’s not a problem. She went to school in the veil. And nobody cared. There are lots of other places that allow it. But not France. Why is it such a taboo, such a problem? It’s sad.”

She worries for her children as a result.

“It’s not only Muslims, but African people, too. We will never have a place in this country. Even if our children are born here, like mine, if they’re not white and don’t have blue eyes, they will be instantly recognisable as ‘not really French’. And this is for life.”

Across from the mosque, enjoying a mint tea, 49-year-old Salaheddine, refuses to believe that his mosque of choice is in any way extremist.

“I don’t know who trained those lost souls,” he says of the attackers. “They probably met bad people at bad times in their lives.”

“But it didn’t happen in this mosque. I can tell you that. They came maybe three or four times. But that’s not a reason to say that the mosque is radical.”

Salaheddine doesn’t want Ms Le Pen to win, and he doesn’t like what she has to say about Muslims, Africans, or the immigrant community in general.

But should the unthinkable happen, and she does somehow win the presidency, he thinks that he and others like him should at least try to weather the storm.

“In the 1990s, I was in Algeria and the Islamic Salvation Front was elected,” he says. “I was voting at a school and I saw hundreds of people voting for them. It was a tidal wave. Whether they were worth voting for or not, they were winning legitimately, and the army decided to shut them down. The election was stolen from them.”

“We have to understand that people voting for Marine Le Pen are not aliens, but French people. It’s anti-democratic to demonise her party just because you don’t like it. If she wins, she wins. As we say in Arabic, Allah will her help her.”

The café in which we are speaking, Le Fidele, is filling with men in various styles of religious dress. Their beards vary in length and their skin in hue: this is a multicultural space, too. The café is cast in a hard neon blue by lights above the counter, and looks like any other slightly down-at-heel corner café, except that, where the booze should be, a Koran sits tucked away instead.

In a corner at the back of the room, Samir, 44, sits brooding. He’s lean, bespectacled, and alone. He speaks in a soft, measured manner that is at once both soothing and somewhat disquieting.

“My religious convictions do not allow me to vote,” he says. “Of course we live in France. We cannot expect this country to become an Islamic state. Don’t misunderstand me. I’m not talking about the organisation. But it doesn’t interest me to vote until there is a candidate who represents my own vision.”

What exactly his vision entails requires a little probing. Samir doesn’t believe that the Charlie Hebdo or Bataclan attacks were in any way conducted by bona fide militants. Instead he believes they were “false flag” operations initiated by France and its allies to demonise the Muslim population and to justify crimes against it.

“Yes, these attacks happened,” he says. “We can’t deny it. We can’t hide it. But is there a conspiracy behind them? Definitely. Personally, I think that the people behind them are enemies of Islam. It makes sense. Islam is growing in Europe and people are trying to find ways to bring it down.”

“We’ve seen this movie before,” he says, hinting at the September 11 attacks. “We saw it 15 years ago.”

But here’s the kicker: even Samir is more pro-Le Pen than pro-Macron.

“When Marine Le Pen talks about globalisation, the euro, and so on,” he says, “I would say that’s a good thing for the French people to hear.”

“I think if a new political figure had emerged with Le Pen’s ideas, but without the Front National behind him, he would have become president. Sometimes when she’s talking, she’s saying very good things. That’s why she will never be elected. Because she’s too dangerous.”

This is where things begin to get a little complicated, at least to anyone fixated on the increasingly out-of-date left-right divide: it’s the point at which that false dichotomy begins to break down in the simmering cauldron of ideas older than today’s identity politics.

Asked about the contradictions inherent in his feelings about Le Pen, Samir puts it this way: “When you get old enough, it’s up to you to see the good and bad in things, and you begin to realise that the system is not as black and white as it seems”

“Even if 80 per cent of Marine Le Pen’s ideas are bad,” he says, “20 per cent of them are still good and we can use them.”

Directly opposite Masjid Omer, the old headquarters of the Union Fraternelle des Métallurgistes sits gentrifying slowly. On its façade, a plaque honours the life and work of Jean-Pierre Timbaud, a Resistance fighter and Communist leader who organised clandestine trade union committees during the same war Dalil Boubakeur is commemorating not five kilometres away. It turns out that class still matters in these parts. It’s the economy, stupid, mais bien sûr.

Back at the Grand Mosque, Mr Boubakeur is struggling to push back against the anti-globalist leanings of his co-religionists. He has a warning for those leaning so far in that direction that they now rate Ms Le Pen more highly than one may have assumed.

“A vote for Marine Le Pen is a desperate vote and I beg those thinking about it to find hope, wisdom and reason again, and to unite together with the whole Muslim community,” he says.

“We are for togetherness — the togetherness of the national community — without any distinction in the spirit of secularism. Which is absolutely fundamental to us.”

What happens, though, when the foundations shift? What happens when even the reviled start nodding?

If you would like to read more independent journalism like this, please consider becoming a monthly patron.

Published in General

It is such a muddle. Apolitical Islam=Fine (to the extent it exists); political Islam=Frightening. That is the issue with all religious practice: So long as it does not wield the power of the state and does not embrace violence it is tolerable even if weird (from a non-believer’s perspective). Islam is so impenetrable from an outsider’s point of view that we are entirely reliant on others to interpret it for us. So then it is a game of “who do you trust”? It doesn’t help that one of its tenets approves of lying in support of Islam.

@Rodin is right on the money. Islam is difficult to understand, especially when we have so many western academic/journalistic apologists, and propagandist on both sides of the political spectrum, writing about it. Add to this mix the Islamic practice of Taqiya (being allowed to lie under Islamic law) it takes a great deal of effort to sort out fact from fiction. I appreciate Claire’s attempt to enlighten us, and bringing in new information sources to review, but her obvious partisanship for Macron and her world view nativity makes me take the article with a little grain of salt. Being skeptical is not being paranoid, but in my experience, being a little skeptical and paranoid will help keep you alive.

For real, people think this?

The above is an issue for me as well. I don’t know how to get around it, or if we ever can.

I find taqiya too much effort when I could simply lie.

Thanks, Claire. And thanks, too, Mr. Clayfield.