Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Want Satisfied Parents? Empower Them to Choose

Want Satisfied Parents? Empower Them to Choose

Parents are more satisfied with their child’s learning environment when they choose it. Indeed, as economist Tyler Cowen put it recently, “the single most overwhelming (yet neglected) empirical fact” about educational choice programs is that “they improve parent satisfaction.” A slew of new reports add a number of hefty boulders to the mountain of evidence.

As I explained in greater detail last week, bureaucrats tend to focus excessively on test scores but parents take a more holistic approach to evaluating the quality of an education provider. As Cowen notes, “parents may like the academic programs, teacher skills, school discipline, safety, student respect for teachers, moral values, class size, teacher-parent relations, parental involvement, and freedom to observe religious traditions, among other facets of school choice.” Parents know their children are more than scores.

Voters generally tend to reflect the views of parents more so than education technocrats. In a recent survey from Public School Options, only 14 percent of voters said they “consider state standardized test scores the critical factor in assessing a student’s overall success in school” and 78 percent said that schools “should never be closed primarily on the results of that particular school’s average” on the state’s standardized test. Moreover, 65 percent said they “believe an ongoing summary of each school’s status using a dashboard of multiple measurements would be more helpful to parents and policy makers” than a “system that provides a single letter grade for each school.” If we want an education system that considers the individual needs of each child rather than grading schools on a few narrow measures of performance for an imagined “typical” child, then we should entrust parents with holding education providers accountable for academic outcomes.

Education savings accounts (ESAs) are one way to accomplish that goal. With an ESA, parents can customize their child’s education, using it to pay for private school tuition as well as tutors, textbooks, online courses, educational therapy, and more. The ESAs are typically funded from a portion of the funds that the state would have spent on a child at his or her assigned district school, but they could also be funded through tax-credit eligible donations. In a 2013 survey, Arizona parents of students with special needs expressed unanimous satisfaction with the educational settings they chose for their children using the ESA funds. Moreover, the lowest-income families were the most likely to express dissatisfaction with their assigned district school (67 percent) and the most likely to say they were “very satisfied” with the education their child obtained through the ESA (89 percent).

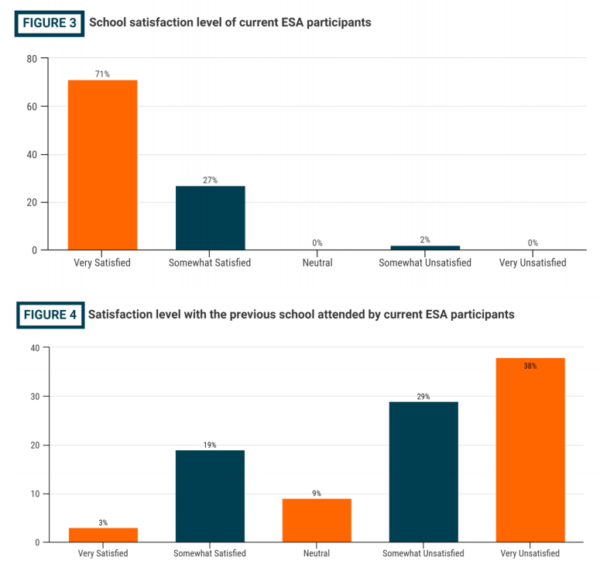

Last week, Empower Mississippi released a similar survey of parents of students with special needs using Mississippi’s ESA. Participating students had an array of conditions, including autism, hearing or visual impairments, traumatic brain injuries, speech impairment, emotional disturbances, and more. The results mirrored those from Arizona. As shown in the two figures below, most participants were dissatisfied with their previous experience in their assigned district school (67 percent) but they overwhelmingly expressed satisfaction with the educational setting they chose using ESA funds (98 percent).

Source: Empower Mississippi

These views may not reflect the views of all Mississippi parents, or even all parents of special needs children. Nevertheless, they show that the district schools are not serving a subset of the population and that those parents believe their children are much better served in settings that they choose.

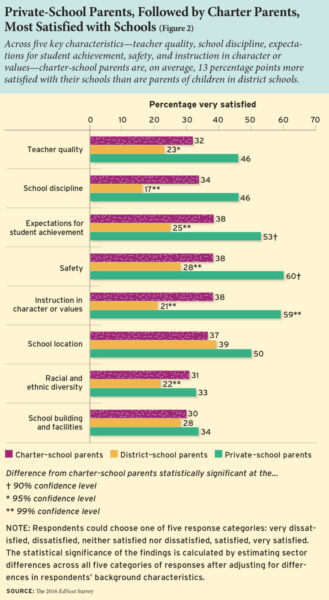

That said, national survey data indicate that parents generally are happiest at chosen schools. In a recent survey, Education Next asked parents of children attending a variety of different types of schools about their levels of satisfaction with their school’s teacher quality, school discipline, expectations for student achievement, safety, instruction in character or values, location, racial and ethnic diversity, and the school building and facilities. Parents were significantly more likely to express satisfaction with schools that they chose than the district schools to which their child was assigned. Moreover, as shown in the figure below, parents were more satisfied with private schools, where they generally pay at least some tuition, than at public charter schools, which do not charge tuition.

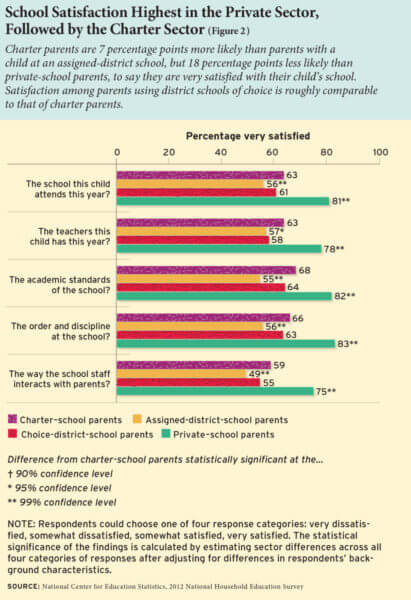

Education Next also published parental satisfaction data that the U.S. Department of Education under “the most transparent administration in history“ had collected but never reported publicly. As Harvard Professor Paul Peterson explained in the Wall Street Journal:

As we were completing our analysis, we unearthed a U.S. Education Department survey from 2012 that posed similar questions to a nationally representative sample of parents, and we found that the Obama administration has never reported the charter-school results from this survey, although the raw data are publicly available for others to analyze.

Digging into this data, we discovered that this survey, too, reveals both private-school parents and charter parents to be more satisfied with their schools than parents with children assigned to public schools. They are also more satisfied with teachers, academic standards, discipline and “the way the school staff interacts with parents.”

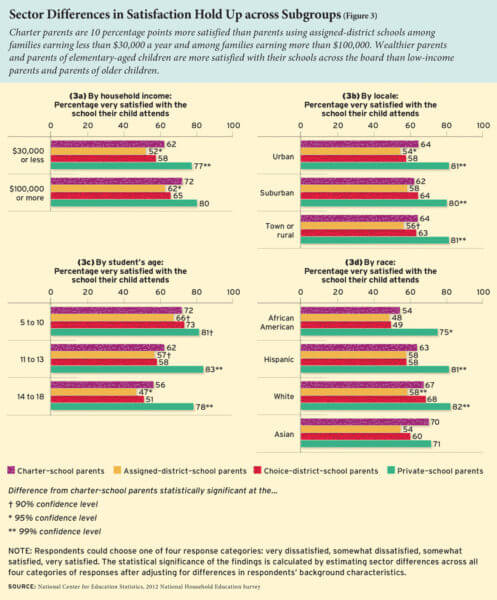

Once again, the DOE survey found that parents are more satisfied when their children attend schools that they chose, particularly private schools. As shown in the figure below, low-income parents are significantly less satisfied their assigned school than wealthier parents, and they are also more satisfied when their children attend private schools than schools in any other sector. The same is true for parents of all ethnic backgrounds, whether they live in the city, the suburbs, or rural areas.

Parental satisfaction levels do not conclusively prove that students are receiving a better education at any given school, but neither do standardized test scores. As Tyler Cowen reminds us, “how the buyers like the product is the fundamental standard used by economists for judging public policy.” Parental satisfaction should not be the only metric that policymakers consider, but it should be chief among them. And on that metric, the evidence is clear and conclusive: parents prefer schools that they choose for their children.

Technocratic attempts to determine school quality using quantifiable and standardizable metrics like reading and math scores fail to capture a wide range of outcomes that we want from education. Moreover, when such narrow metrics are used to reward and punish schools, they can create perverse incentives that narrow curricular options and stifle innovation. By contrast, parents consider a wider variety of metrics, both quantifiable and non-quantifiable.

Policymakers should work to empower parents with a wider range of educational options through policies like education savings accounts, and education policy wonks should direct their efforts toward building institutions—like independent certifiers, expert reviewers, and platforms for student and parent reviews—that help parents make informed decisions. That is the surest way to foster innovation and improve the quality of education available to our nation’s children.

Cross-posted at Cato at Liberty.

Published in Education

Great article. It’s a strong argument, well presented.

It’s really cool when something obvious is backed up with statistics. Unfortunately liberals accept neither. Great post.

Why don’t Shanghai and Tokyo have a Silicon Valley? If test scores are everything than they should have them.

I would like to see these opportunities spread out as far as possible. Under the current system the desire of the affluent to get the best for their children is not doing the rest of us good. This is not an evil desire, and we need ways to make it work for the rest of us, not against us.