Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

The Night of Fire

The Night of Fire

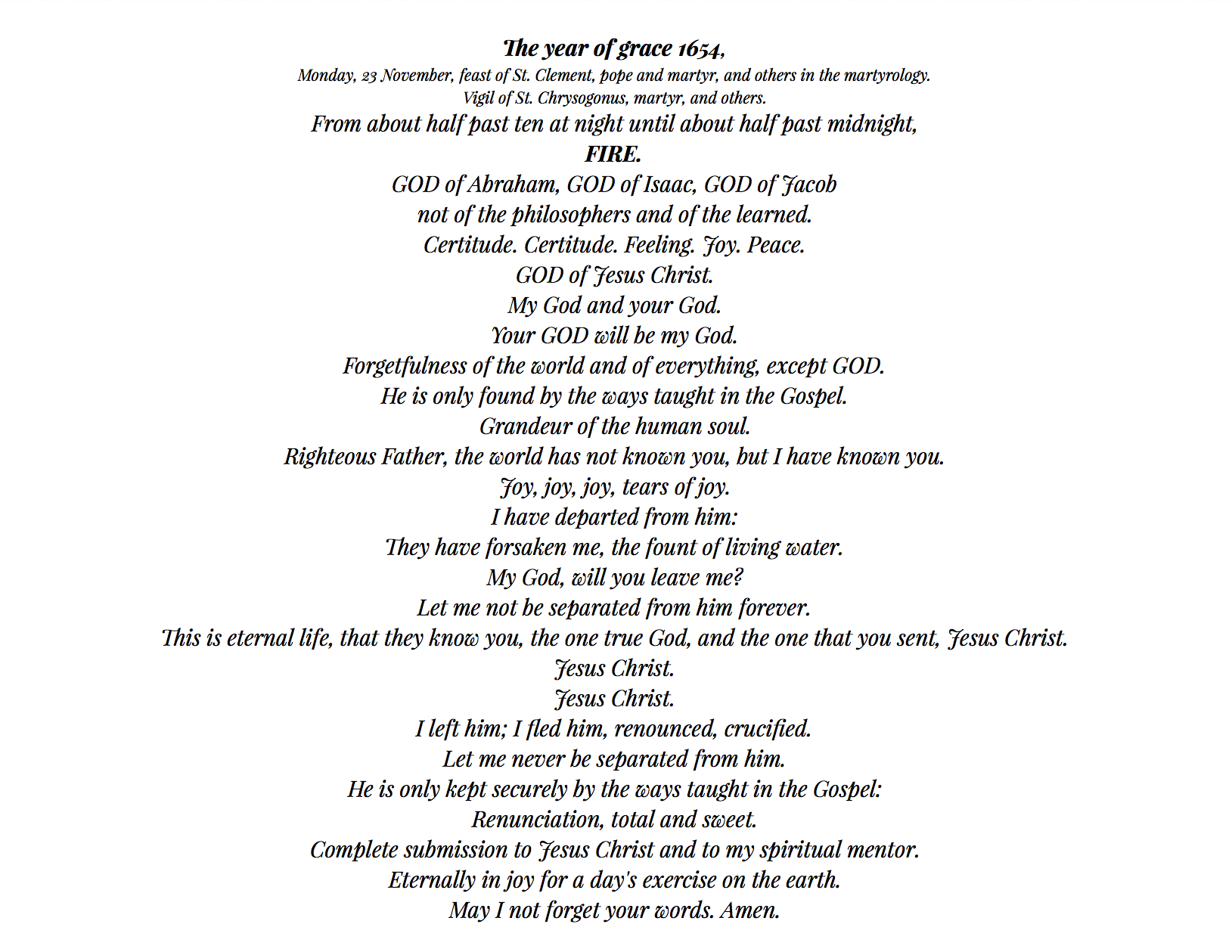

Blaise Pascal, mathematician, scientist, inventor, and philosopher, a man who from the age of 16 had been making historic contributions to mathematics and the physical sciences, who, despite a sickly constitution and a capacity for intense abstraction nonetheless oversaw the material construction of his experiments and inventions with great zest, was barely past 30 when saw something unexpected one raw November night. He saw fire. The vision of it so branded him that he sewed the record he made of it, his Memorial, into his coat, carrying it with him the rest of his life:

In school, I was taught that Pascal meant it when he said, “GOD of Abraham, GOD of Isaac, GOD of Jacob / not of the philosophers and of the learned” – that after his night of fire that fateful November, Pascal really did renounce all scientific thought as libido excellendi, the concupiscence of the mind. Bertrand Russell called this renunciation “philosophical suicide.” Nietzsche called Pascal “the most instructive victim of Christianity.” By contrast, Pascal’s sister and hagiographer, Gilberte, who first related the renunciation, regarded it as a triumph of faith over the illusions of this world. Years earlier Jansenists had stayed with the Pascal household, and young Blaise had convinced his sisters to adopt Jansenist teachings – teachings so passionately attached to Augustine’s vision of man’s total depravity as to be almost Calvinist despite their nominal Catholicism — so attached as to believe even reason itself was corrupt, a chimera, a mirage misleading the minds of men. The mirror we see in so dimly is far too dim to show reason undistorted, or at least not the reason that matters.

Hence “not of the philosophers and of the learned.” Quite a grim prospect for any of us trained to believe that the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob is also the God of the cosmos and of all who study it. And what would it mean if the “not” were true? What would it be like to abandon the whole edifice of scientific understanding, to kick off the twin traces of evidence and proof, and plunge, headlong and burning into… something else altogether. I am not sure what. Only that for a very long time, it has been hard for me not to wonder.

And so, the story goes, the man who, only months before, had been collaborating with fellow mathematician Fermat in founding an entire new discipline, probability theory, abandoned it all to become first a sarcastic theological crank (see the Provincial Letters), and finally the tortured soul dying tragically young, leaving his magnum opus, an existential defense of Christianity, so unfinished that only scattered fragments and notes could be gathered and published – the Pensées.

Or at least that’s the story as it’s commonly told. The real story is not quite so pat. Accounts differ as to how deep Pascal’s renunciation of scientific thinking went. Like Nietzsche and Russell, the folks at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy seem to believe it went pretty deep. Other sources, though, point out he never did fully abandon his interest in math and science, and still pursued the odd project here and there. Moreover, scientific habits of mind do not disappear overnight, even if you’re not doing science. Certainly, the famous Wager of Pascal’s Pensées shows a mathematical mind still at work. It isn’t often that a theological conceit with all the deference of a mugging is credited with mathematical innovation, but Pascal’s Wager is counted as one of the first uses, ever, of decision theory. (As well as a kind of argument irresistible during election seasons: “Yes; but you must wager. It is not optional. You are embarked. Which will you choose then?” – of course Pascal, already believing his beliefs, thought everyone must see themselves as already embarked, as already consigned to his binary choice, no matter how much unbelievers might see it otherwise.)

Still, it’s worth asking why the renunciation went as deep as it did, when it did. After all, Pascal had been a Jansenist for years while remaining active in scientific circles. His mind had been converted long before. The night of fire, though, was a conversion of the heart.

For Pascal, the heart was supremely important, though not in the romantic or emotional sense, or even, necessarily, in the same sense other pious Christians speak of it. Perhaps the heart meant the faculty of perception “transcending reason and prior to it”[2], what Schumpeter (and Sowell after him) called Vision. Within mathematics, Pascal spoke of an esprit de finesse that leaps ahead of reason and draws it onward. Polya would later quite charmingly call this intuitive spirit just “guessing,” though Polya would make guessing into an art. Polanyi would point out that this intuition, though not emotion itself, demands emotional commitment. Pascal opposed l’esprit de finesse to l’esprit géométrique, the “geometric spirit” of articulated, deductive reasoning – the faculty of the mind that, however persuasive it might be, is often just on janitorial duty, tidying up the syllogisms after l’esprit de finesse has passed. The “heart” (coeur), as Pascal spoke of it, seems to encompass the intuition preceding reason just as it encompasses the “revelation” that reason is in vain. If this seems contradictory, perhaps Pascal would point to Jeremiah 17:9: “the heart is deceitful above all else.” Even so, “some faint glimmer or trace of the instantaneous, clairvoyant understanding that the unfallen Adam was believed to enjoy in Paradise”[2] must remain, else faith and reason would both be blind.

And the eyes of Pascal’s heart saw fire.

Fire – fire consuming the flowering thorns on sun-bleached prairies; fire arcing from the tips of the branches of roadside trees, from towers and steeples, weaving a net as visible to the mind’s eye as it is invisible to the body’s eye: these visions are not hard to have, and not particularly special, either, if no moral sense gives them meaning. There’s speculation that Pascal, like Hildegard of Bingen before him, suffered migraines, headaches causing hallucinatory auras. If so, both visionaries made something out of those auras, they made them into something revelatory, unlike other sufferers who may just regard the auras as a nuisance, an impediment to everyday adult responsibilities, and all the more painful for being so.

But then, Pascal, for all his accomplishments, never did lead what most of us would call a life of adult responsibility. He never held a job. If his sister’s account is to be believed, not only was he so sick in infancy that he screamed continually for over a year, but he “continued to be so ill that, at the age of twenty-four, he could tolerate no food other than in liquid form, which his sisters or his nurse warmed and fed to him drop by drop.”[1] Pascal relied on nursing care not only throughout his sickly childhood, but throughout adulthood as well, exhibiting “an almost infantile dependence on his family.”[1] By contrast, I suspect the attitude in most modern American households would be, “If you’re well enough to scale the heights of intellectual and spiritual achievement, well enough to mortify your own flesh in penance (something Pascal did in his later years), then you’re also well enough to feed yourself like a normal adult, thank you very much!”

But then, Pascal, for all his accomplishments, never did lead what most of us would call a life of adult responsibility. He never held a job. If his sister’s account is to be believed, not only was he so sick in infancy that he screamed continually for over a year, but he “continued to be so ill that, at the age of twenty-four, he could tolerate no food other than in liquid form, which his sisters or his nurse warmed and fed to him drop by drop.”[1] Pascal relied on nursing care not only throughout his sickly childhood, but throughout adulthood as well, exhibiting “an almost infantile dependence on his family.”[1] By contrast, I suspect the attitude in most modern American households would be, “If you’re well enough to scale the heights of intellectual and spiritual achievement, well enough to mortify your own flesh in penance (something Pascal did in his later years), then you’re also well enough to feed yourself like a normal adult, thank you very much!”

In some circles, habitual suffering does seem to excuse a body from everyday obligations. In others, it seems to impose extra duties. (Thou Shalt Suffer Extra-Discreetly. Thou Shalt Endeavor Doubly To Not Impose.) Not that these circles are mutually exclusive – there’s no rule saying the same social circle must treat all who suffer equally, despite differences in social standing, other gifts, and the suffering’s nature. We ordinary mortals sometimes surmise that suffering spurs not stifles genius, as if suffering itself could cause genius. We may overlook, though, how much the great suffering geniuses rely on their caretakers to manage life’s little inanities for them. Stephen Hawking certainly had to depend on others to turn his paralysis into opportunity. Pascal was, by comparison, far more able-bodied. Though Pascal suffered greatly, he was also cared for greatly, so greatly it’s not hard to suspect he could have gotten by on less.

Had Pascal been expected to shift for himself more, would he have burned as brilliantly? Perhaps. But then again, perhaps not.

The world of math can be an escape from suffering, a winter Eden – the bones of the trees of life and wisdom freed from the flesh of their leaves, the pages of innocent snow awaiting inscription, all stilled, all crystallized – a nature “out of nature,” set apart from the bloody, sticky summer which commends “whatever is begotten, born, and dies.” The mental stillness demanded by l’esprit géométrique beckons as a refuge from the ravages of mind and body, but entrance to this refuge costs a fee. Some of my own most peaceful memories are of solving math problems to escape life’s vicissitudes – while feverish, in a hospital, in the rubble of a shattered future. But even then, no matter how restorative, the problems demanded something of me first: If I couldn’t muster that something, the hope of refuge was lost.

It’s not hard to imagine that a man like Pascal, dogged since infancy by suffering, first fell in love with math because he could make it a refuge, a pursuit absorbing enough that his suffering ceased to matter. Is it possible that he fell away from math and into theology and mysticism when, despite all the care he received, he reached a point where he could no longer get his suffering to cease to matter?

Neither mathematical nor scientific reasoning is intended to answer suffering. The freedom they offer from suffering is just the freedom of a perspective where suffering doesn’t matter either way. That perspective can be a great comfort as long as there’s enough oomph to maintain it. When the oomph is gone, though… Inhabiting a winter Eden means fueling your own fire, else you freeze. When your own fuel runs out, where do you turn? Perhaps to some greater fire outside yourself. Perhaps to the fire so great it appears to be a God. And perhaps that great fire is an illusion. Or perhaps it isn’t. The only witness to the fire is the heart, as clairvoyant as it is deceitful.

No wonder Pascal wagered.

For @nanda-panjandrum.

- Blaise Pascal, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Blaise Pascal, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

I think Socrates is the only philosopher in whose behalf the boast was made that he could drink everyone under the table. Read your Symposium. Gobsmacking.

Beautiful article, leaving its reader with much to contemplate. Thank you.

Ok, Midge & co., here’s something to put in your pipe & smoke!

Midge,

I find Russell a fool and Nietzsche a lunatic. Neither should be allowed to pass judgement on Pascal. Their disdain for morality, religious or secular, is never associated with two world wars, a Hitler, or a Stalin. Some people don’t rob banks they just leave the vault unlocked. I feel the same way about Voltaire and Leibnitz. Voltaire laughs at Dr. Pangloss. Meanwhile, Voltaire stands knee-deep in the blood of the reign of terror. I think Leibnitz is highly underrated and Voltaire highly overrated.

The standard treatment may be standard but it can also be wrong.

Regards,

Jim

OHHHHH! Because you’re, in the infinitesimal limit, projecting to a sphere, or a cylinder: The series of infinitesimal, planar projection surfaces you use as you turn your head combine to form a hemisphere or a hemi-cylinder. But, (assuming you’re facing due East) you could also imagine using a projection plane that’s infinitely wide, and it would contain every point of the horizon — as a line, not a curve — except for the ones toward the North and South poles.

Yes, it can be seen either way.

“Implied”, yes. You had to infer a curvature. What you saw was straight in each moment.

I understand everything you’re saying, here, but, dang it, I can’t find @titustechera ‘ comment talking about piling on abstractions, so I don’t know what he meant, so I can’t answer.

It’s an obvious-enough inference to make, though. This “horizon” thingie, always perpendicular to me whichever way I turn and equidistant… sounds rather circular…

Right. But you didn’t see curvature. Or, did you? You were talking intuition, not perception.

Thanks for all the meat, Titus. I still (mostly) feel like I’m reading Alan Sokal’s paper, but I’m slogging through it.

Heh! That was a fun one–is it twenty years now, or thereabouts… I’m glad you’re putting in the effort. This is part of my radical takeover of Ricochet…

No, I don’t think I did, but intuition and perception are difficult to tell apart.

Speaking of the philosophy of science–here’s what I’ve been writing on the politics of science.

…Radical takeover?…Oh, yes, please, TT!

Here’s a kind of introduction to my thoughts on Pascal & Descartes as they relate to America.