Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

A Gene Therapy That Works … And the Ethical Dilemmas It Presents

A Gene Therapy That Works … And the Ethical Dilemmas It Presents

Metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD) is Alzheimer’s on speed. Children born with the most common form of the disease will die by age five, due to atrophy of brain tissue. The incidence in the general population is estimated to be 1 in 40,000 to 160,000 births.

Metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD) is Alzheimer’s on speed. Children born with the most common form of the disease will die by age five, due to atrophy of brain tissue. The incidence in the general population is estimated to be 1 in 40,000 to 160,000 births.

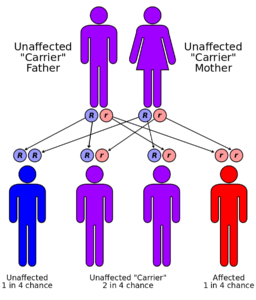

Unlike Alzheimer’s, MLD has a known genetic cause. It has an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern, which means a child must inherit a defective, recessive gene from each of two carrier parents to be symptomatic. That suggests the frequency of carriers in the population is 1 in 200 to 1 in 400. But for couples who are both carriers, the odds of a child with MLD are 1 in 4.

Post-natal testing does not work on MLD. The enzyme test that reveals the disease has a 7-15 percent false positive rate due to other, less severe conditions affecting the same body chemistry. Unless a specific genetic test is done on the parents or the pre-natal fetus, the first time most affected couples will know is when their child exhibits unmistakable symptoms. By that point, the disease in untreatable and irreversible. And there are 1 in 4 odds that any future child of theirs will die the same way (see illustration).

There is hope. This is a case where post-natal gene therapy seems to be effective. An MIT Technology Review article describes a technique to modify extracted stem cells with a corrected gene and reinsert them in the child’s body, reversing the disease. As far as can be determined with a small sample size over a few years, it appear to be safe and effective: that is, a genuine cure. Amazingly, the whole development in an Italian clinic has been supported by national telethons and philanthropy. Huzzah for the Italians!

The MIT article raises several issues, but without pause or analysis. I extract two passages to frame the dilemmas:

…treatments have been purchased by British drug giant GlaxoSmithKline, which is pursuing commercialization of the therapies. By adding correct DNA code to cells, gene therapy has the potential to erase devastating illnesses with a one-time treatment.

On one hand, a GSK pickup means the therapy will no longer live on charity. But what will it cost? Remember, this is a cure, offering no recurring revenue stream from afflicted patients. The costs of conclusive clinical trials and manufacturing must be amortized across the limited number of victims, one time each. And, of course, who pays? And if not the individuals concerned, what onus is there on others to pay for a stranger’s care?

Mind you, this is a cure for the child’s lifetime only. It does not modify the germ cells. A child with MLD who survives to reproduce — which will now happen at far greater frequency — will pass a copy of the bad gene to every offspring. Good for the individual, bad for the human gene pool, creating further potential costs down the road. Some believe that tampering with the germline is ethically problematic, but this case demonstrates the down-side of not doing so. Is it counterproductive — is it ethical — to save the current suffering at the cost of more in the future?

…[the mother] also disagreed with the Italians’ advice to get a prenatal genetic test during her two subsequent pregnancies to learn in advance if the fetuses would be affected, as she wouldn’t consider abortion. She had four more children, three of them in 2014 when she delivered natural fraternal triplets (there are one-in-8,100 odds of that). One of them, Cecilia, also had inherited the MLD genes. The Italians accepted the second baby into the study and treated her…

The American couple in question now have eight children, three (one deceased) with MLD. They live on a single house remodeler’s income. They are a charity case. Luckily, the Italians stepped in, not just once but twice.

What are the chances such a family would be able to afford GSK’s cure in the future? Should they be subsidized if they continue to procreate, knowing there’s a 25% chance that their children will need care they cannot afford? Should society support this? Can an obligation be created to test and yes — abort — once the hazard is known? What can we say about the ethics of such parents, or, on the other hand, a societal decision to turn its back on children born in such a situation?

We are going to see a spate of novel and effective gene therapies in the near future, due to advances such as CRISPR, but having cures is not going to end the dilemmas of treatment.

Image Credit: en:User:Cburnett – Own work in Inkscape.

Published in Healthcare

A huge ethical dilemma covering so many aspects of the economics of medicine and morality. Nice post.

I have moments where I struggle with the ethics involved, but then I remember: we are human. Humans get to make choices. I do not get to decide for someone else that they cannot have children, nor do I get to decide that their children cannot have children. With any luck, if they are saved, they would choose not to have children or to have the money to afford the cure. The major ethical concern for me, as a healthcare practitioner particularly, is how we choose to put a price on something like that.

How do we put prices on live-saving treatment right now? We put a price on liver transplants, on pacemakers, on artificial valves. We put a price on many things.

I think we need to examine ourselves and realize that as ugly as it sounds, life-saving technology has a price. I cannot believe I even typed that. I did. Life-saving treatment has a price. Life itself is priceless, but not everyone will have everything. Not everyone will get a perfect liver. Not everyone will live cancer free.

I think it is less a matter of if it is right and more a matter of how we determine who gets treatment once the US is on the hook for all healthcare.

Fascinating post. I live in Italy and had never heard of any of this. I don’t have answers for your ethical questions, but I would love to read what others think.

Thank you, Locke On, thought-provoking post. Main Feed!

What a great post!

Very good question.

If @merinasmith, @thedowagerjojo, @rachellu, and @jenniferjohnson are available, I’d be interested in hearing their thoughts.

To me, this is a really good example of why germ-line therapies should be considered and — when appropriate — adopted.

What a hopeful, yet heartbreaking, post.

Two years ago, the daughter of our dear friends, and her husband, discovered that they both had a gene with an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern (not the one described in this post, but it worked exactly the same way).

Their beautiful son (their first child) lived for eleven days.

They have decided not to have any more biological children, and have since adopted a wonderful little boy. Their loss, and their decision, was devastating to them, which makes it all the more a joy to see their happiness now.

The outcome of the germ-line therapy for this particular issue, as described here, is miraculous, but very troubling. I don’t know the answer.

In medicine we fix broken people. A one and done cure is best and most efficient. There are considerations that make it messy – age, health, quality of life, economics. One thing is certain, we never consider how fixes may affect future generations. We can correct many congenital and inherited problems, but we never and should never consider whether these corrections should be passed on to future generations. This is the repulsive stuff of eugenics for those who think they can play God. That line of thinking ignores our principles, “that all men are created equal and endowed by their Creator of certain unalienable rights.”

Tough ethical questions. I don’t think the answers will be the same for every person, but I most assuredly do not think people should be told by government what they HAVE to do. I have other questions–if the gene is passed to every offspring of those affected and cured, what happens when they marry someone who does not have the gene? How likely is it to be passed to the offspring of the children of the carrier married to a non-carrier? Also, how much does the cost of treatment change when it is more commonly done?

For myself–if my husband and I were carriers of something like this or Tay-Sachs or other devastating diseases, I would adopt. I would never have an abortion however. And I am happy for my taxes to be used for cures like the one described in the OP, though I realize we do not want to encourage people to regard outsourcing their medical care to taxpayers as trivial.

Edit: Excellent points by Team America and Midge below.

Your Comment…The rarity of this disease should mean that getting insurance for it would cost little. As for the issue of those cured passing it on to future generations, we should remember that science advances, and that GSKs monopoly is temporary.

An interesting post, Locke On!

I’ll point out it’s not a new ethical dilemma, though, nor an ethical dilemma caused by stem-cell anything.

Any lifesaving or sufficiently life-improving drug allows some of us “defectives” who otherwise would have likely died single (say, in childhood) and childless to survive and reproduce, and if our “defect” is heritable, creates even more people with that “defect” in the next generation. Even a disease as commonplace and uncontroversial as asthma alters our germlines if those of us who would have died in childhood from asthma before modern treatment (and generation Midge is the third such generation in my family) instead survive and bear children.

I will be honest: more than one heritable disease in my family had me seriously questioning whether I ever should reproduce.

Fortunately, the man who married me enjoys excellent health, and does appear to carry genes (as far as we can tell, which isn’t very far yet) that seem to dilute my bad genetic traits – yes, we checked (as much as can cheaply be checked right now) before conceiving. If there were an affordable way to select for and/or modify my germline in a way that respected life, so that my children would suffer less from having me as their mother, I would do it in a heartbeat!

In that situation, I believe their children would then be guaranteed carries. If the person who’d undergone the stem cell therapy married a carrier, their children would be guaranteed to have the condition.

Once you know you carry certain genes, though, you risk becoming uninsurable: a gene highly likely to cause a later illness is a pre-existing condition. David Friedman has written about the costs that come with the benefits of knowing what’s in your genetic library – here, and in other places as well, I’m sure.

You’re right, though, that patent monopolies – while useful for rewarding the creation of benefits to society that might not otherwise be created – are rightfully only temporary. Member @duaneoyen and I both look forward to inhaled corticosteroids for asthma going generic. There are additional obstacles, though, with inhalers, because generally it’s not the drug, but the method of delivery, that’s the novel portion of an inhaler:

and

(emphasis mine)

Intellectual-property protection on medical devices is important, but the specific combination of possibly too-stringent FDA bioequivalence standards for generics with potential rent-seeking on medical-device patents creates some interesting (by which I also mean expensive) results. How much cheaper could these treatments be if regulation weren’t as intrusive? I would bet noticeably cheaper – though as @mendel points out, not necessarily much cheaper, and he has a point: if life is precious and suffering awful, it’s only reasonable to suppose there will be people out there willing to pay as if life is precious and suffering awful.

Tom–my question was when the cured carrier married a non-carrier. Is that how you read it?

Yes.

Unless I’m deeply mistaken, a cured carrier will pass the gene to his or her children. If the spouse is a non-carrier, then the children will be a carrier, but exhibit no symptoms; if the spouse is a carrier, then the child is guaranteed to be symptomatic.

Science is not my specialty, but doesn’t it say in the OP that if both parents are carriers there is a 1 in 4 chance the children will be symptomatic?

Both correct.

That’s if both parents are carriers – that is, they each have one good gene copy, one bad. In the situation where a spouse was symptomatic, but saved by the gene therapy, their germ cells will all have two bad gene copies, so every offspring gets one, regardless. The unknown is the other spouse – if that person has no bad copies, then every child will be a carrier, but not symptomatic. If that person is a carrier, then half the children (on the odds) will get two bad copies and be symptomatic, the other half will be carriers with one bad copy. If both spouses are symptomatic, then every child gets two bad genes and is symptomatic.

Ah, Tom, those who suffer a recessive malady do carry two copies of the defective gene, but “carrier” is often shorthand for someone with only one copy of a recessive trait, and maybe that’s causing the confusion Merina noted.

Person with two copies marries person with one copy: half their children are expected to have both copies and get the malady, and the rest will be “carriers” (with one copy, asymptomatic).

Two “carriers” (people with only one copy apiece) marry each other: a quarter of their children can be expected to get both copies, manifesting the malady; half are expected to asymptomatically carry one copy; and the remaining quarter are expected to have no copies of the gene.

It is of course possible for parents at the least nonzero risk of passing down a genetic disease to pass it to all their children – a three-quarters chance your kids won’t suffer doesn’t guarantee against all your kids suffering, it’s just unlikely. I think this reality is part of the psychology of this kind of suffering: to be so “unlucky” in life that even blind chance seems against you can happen, and when it does, it’s perhaps even harder to not feel like a freak.

Thanks Midge, Tom and LO. As I said, science is not my specialty, but the answer to inheritability doesn’t really change the ethics IMHO. There will never be easy moral answers to these questions, but I hope we can all agree that government mandated answers like required sterilization or abortion is not a road we want to travel.

You’re very welcome.

I didn’t know such a thing was being suggested.

In an age of euthanasia and the existence of a party that wants abortion up until birth, it will be suggested.

I adopted a neutral stance in the OP, but my take away from this case is that germ line editing is such instances is not unethical, but may rather be imperative when and if feasible. (I have no knowledge of whether it is or will become feasible in the specific case.) To the extent we are storing up future trouble by saving symptomatic children who will procreate – no, I’m not in favor of any such prohibition – our best way out is further progress. I see little moral difference between fully editing MLD out of the human genome, and eradicating smallpox. The prevention of future disease and human misery is the outcome, genetics and technology are simply the means.

I will hasten to add that I see it differently for germ line editing when there is a not a clear cause-effect relationship to some fatal or obviously deleterious outcome. That’s much more debatable, down that road lies meddling with what it means to be human.

A wonderful conversation here. I am the mother discussed in the article (thank you google alerts for keeping me always on top of MLD and gene therapy information). I have appreciated the discussion and share some of the same dilemmas, as well as the dilemmas actually living with this disease and treatment.

First, we had 4 children when we first heard of MLD with their diagnoses, did not plan to ever have any more, and were preventing. Carrying spontaneous triplets at the point that we were also caring for our terminally ill daughter in our home by ourselves would never, ever have been something we would have planned or asked for. They were coming though, and our belief system told us how that needed to be handled.

1 in 100 of us are carriers for MLD. We never knew it, and those 1 in 100 people, unless a dx exists in their family, do not either. Where do we draw the line of deciding who is a risk and who isn’t, for the future gene pool?

I honestly can say I have never even thought of either of our children who have undergone gene therapy as having their own children in the future (aside from the existing risk to fertility and sterility from chemotherapy). We take things day by day and I pray that we don’t hit the limit of the treatment one day and see MLD take another child.

Continued….I have laid awake at night concerned about the dilemma of where this treatment will lead for the future. Will a company want to take it on, given the high cost and “one and done” treatment? Will insurance pay for it? Will families have to continue to seek treatment outside the US and funded by non-profits such as Fondazione Telethon?

We are hoping that the coming months and years will lead to some of these answers, as we work to bring funding to the US for our Italian Doctor.

@saintaugustine and @rachellu are more qualified to opine on the natural law argument here, but the simplest application to the ethical dilemma doesn’t strike me as difficult. Biology and reason would indicate that “Alzheimer’s on steroids” represents a defect that, if it can be cured by medicine, should be. I’m not sure what the assessment on people who have the disease treated would be as regards children, but I can’t think (until Midge mentioned it herself) of a case where we say that, because of a congenital heart problem or a propensity towards cancer that people should not have children. If the child is born with the disease, we treat them too, and we move on with our lives.

If the ethical question is not difficult, the practical one is: how do we pay for it?

One possibility is that the gene therapy can be used for many diseases, not just this one -so it may be that the first generation (which is insurable) will provide enough funding to diversify the therapy into dozens of diseases that collectively pay for the treatment. Call this the grocery store model -no one gets rich selling lettuce, but no one starves either.

But if that is not the case, this seems an area where charitable or governmental action is acceptable. Charitable associations are, of course, easier to justify, but government prizes for the research, or the proposed high-risk insurance pools subsidized by government are also possibilities.

Not an ethical dilemma, really. Screening of all relatives of couples who have had an affected child can easily be done with the genetic expertise currently available. Anyone who has a first, second, third degree or higher relative with an affected child can be screened, and his or her spouse screened to assess risk. A person with one copy of the gene would have no risk of affected offspring unless he or she married a carrier. Then they could have prenatal screening. Further, one would assume that pre-implantation screening of embryos could be done. Someone with the disease cured with this treatment would have no risk of having affected children unless he or she married someone who was a carrier, and anyone with the disease who has been effectively treated could have spouse or partner screened to see if their offspring were at risk. Prenatal testing, or pre-implantation testing could be done to avoid affected offspring. With aggressive screening, the disease could well be prevented entirely, even though the recessive gene were present in the population. This treatment could become a cure looking for a disease.

Poor word choice on my part.

I’ve never heard of this disease till today – it wouldn’t have occurred to me to buy insurance for it.

It seems (predictably) to me that this illustrates the strength of universal single payer health insurance.

I pay (over my lifetime of health care levies) 1/40,000th (or even 1/160,000th) of the cost of a single treatment. That ensures that there is a market for the treatment (ie a payer for the critical mass of children who need it when they need it), which encourages investment in medical research (harnesses free enterprise to find solutions) while at the same time providing a significant good to effected children, and (importantly) to their families.

If insurance companies today don’t cover it, why would a single payer government system? Like any of the procedures on the Medicaid proscribed lists in the various states (Oregon most famously) the more likely outcome is that the treatment would be considered too expensive for the benefit it provides and not covered. Death is cheaper and it isn’t that many people, anyway.